Deportation, Circular Migration and Organized Crime: Honduras Case Study

Table of contents

By Geoff Burt, Michael Lawrence, Mark Sedra, James Bosworth, Philippe Couton, Robert Muggah and Hannah Stone

Abstract

This research report examines the impact of criminal deportation to Honduras on public safety in Canada. It focuses on two forms of transnational organized crime that provide potential, though distinct, connections between the two countries: the youth gangs known as the maras, and the more sophisticated transnational organized crime networks that oversee the hemispheric drug trade. In neither case does the evidence reveal direct links between criminal activity in Honduras and criminality in Canada. While criminal deportees from Canada may join local mara factions, they are unlikely to be recruited by the transnational networks that move drugs from South America into Canada. The relatively small numbers of criminal deportees from Canada, and the difficulty of returning once deported, further impede the development of such threats. As a result, the direct threat to Canadian public safety posed by offenders who have been deported to Honduras is minimal.

The report additionally examines the pervasive violence and weak institutional context to which deportees return. The security and justice sectors of the Honduran government are clearly overwhelmed by the violent criminality afflicting the country, and suffer from serious corruption and dysfunction. Given the lack of targeted reintegration programs for criminal returnees, deportation from Canada and the United States likely exacerbates the country's insecurity. The report concludes with a number of possible policy recommendations by which Canada can reduce the harm that criminal deportation poses to Honduras, and strengthen state institutions so that they can prevent the presently insignificant threats posed to Canada by Honduran crime from growing in the future.

Author's Note

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Public Safety Canada. Correspondence concerning this report should be addressed to:

Research Division, Public Safety Canada,

340 Laurier Avenue West,

Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0P8;

email: PS.CPBResearch-RechercheSPC.SP@ps-sp.gc.ca.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the assistance provided by our colleagues at Public Safety Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency, who provided valuable data and insights for the research. We would also like to thank those experts in Canada, the United States and Honduras who agreed to be interviewed as a part of this research project.

Product Information:

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2016

Cat. No.: PS18-32/2-2016E-PDF

ISBN Number: 978-0-660-05186-4

Introduction

Canadian immigration policy requires that non-citizens who have committed serious crimes be removed from Canada and returned to their country of origin. In other countries, similar patterns of circular migration—immigration followed by deportation—have in a number of cases facilitated transnational organized crime links. Most notably, deportation and circular migration played a central role in the development of the maras in Central America, whose origins as Los Angeles street gangs facilitated their re-entry into the drug-trafficking market in the United States (U.S.). Likewise, the deportation of Jamaican offenders from the U.S., Canada and the United Kingdom (UK) has been a contributing factor in a decades-long surge of criminality in Jamaica. This research report examines the impacts of forced criminal deportation on crime and community security in Canada and in the case study country, Honduras.

Honduras is at the centre of a maelstrom of organized violence and is currently one of the most dangerous countries in the world. The country has experienced a dramatic upsurge in violence over the past two decades. San Pedro Sula (142 murders per 100,000), Ceiba (95 per 100,000), and Tegucigalpa (81 per 100,000) are routinely classified as the most violent cities on the planet. Though some improvements have occurred in the past two years, the country remains one of the five most violent in the world. Among the primary perpetrators of this violence are Central American gangs, notably Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18, and national and transnational organized crime groups. Many of these groups are involved in localized extortion and drug trafficking in Honduras, some of which is coordinated from the country's prisons.

Deportees from Canada face a variety of economic and security challenges upon their return to Honduras. As a group, criminal deportees are particularly stigmatized and find it extraordinarily challenging to secure adequate housing, healthcare, education and livelihoods. In a country facing widespread unemployment, their opportunities to secure gainful livelihoods in the licit economy are severely limited. As in many other countries, it is difficult to disentangle the impact of criminal deportees on crime in their country of origin from the challenging reintegration circumstances they face.

This report considers a number of interconnected issues that arise from the relationship between deportation, circular migration and organized crime in Canada and Honduras. First, it examines the prospective threats these deportees may pose to Canada. Second, it assesses the impact of deportations on development in Honduras, which has been identified as a priority aid recipient for Canada, and suffers from some of the worst violence and criminality in the world. The report concludes with a set of policy options to help mitigate the negative impacts of criminal deportation on public safety in Canada and Honduras.

The Honduran-Canadian Context

Latin American immigrants are present in large and increasing numbers in Canada. As of the last census (2011), Statistics Canada counted 308,390 immigrants from South America and 172,020 from Central America. Honduras accounted for only a small proportion of these newcomers (6,525 in 2011) compared with other countries from the same region, particularly Mexico and El Salvador. A Honduran newspaper stated that as of 2011 there were 15,000 Hondurans living in Canada legally and another 10,000 in the country without authorization, or in the process of gaining authorization (Cerna, 2014).Note 1 Immigration from Honduras has increased steadily over the past decade. While only 166 Hondurans immigrated to Canada in 2004, 402 did so in 2014 (Citizenship and Immigration Canada, 2015). A growing number of Honduran migrants also arrive in Canada under the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP). There were no temporary foreign workers from Honduras recorded in official statistics 10 years ago, but there were 464 in 2013, the last year for which data is available (Citizenship and Immigration Canada, 2014). This increase occurred amidst a rapid and controversial expansion of the TFWP (Gross, 2014). The distribution of Hondurans in Canada is not well known, largely because of their relatively modest numerical presence, but also because they are often subsumed into larger groups for statistical purposes (i.e., Central Americans or Latin Americans). Many reports focus on ethnicity or language use, both of which would make Hondurans indistinguishable from many other cultural groups. The distribution of Central Americans generally, however, is well known. The largest proportion (42 percent) resides in Ontario, and about a quarter live in Quebec. Montreal is the Canadian city in which the largest number of Central Americans are located (over 36,000), as confirmed by the 2011 census. Hondurans are present in large numbers in that city and account for a significant portion of that total, but their precise number is not available.

Immigration from Latin America is not a new phenomenon, but it is relatively recent compared to other more long-standing migratory flows to Canada. There were very few Latin American immigrants in Canada before the early 1970s, but a series of factors contributed to a rapid increase through the 1980s, including rising political violence against opponents of U.S.-backed governments, the increasing reluctance of the U.S. and Mexico to accept immigrants and refugees, and the opening of Canada to global immigration (Garcia, 2006b). The expansion of Canada's TFWP in recent years has further increased Latin American immigration, and Honduras is especially active in the program.

While there is relatively little research on Hondurans in Canada, a significant amount of research has been conducted on Hondurans in the U.S. The number of documented Honduran immigrants is much larger in the U.S.; recent studies estimate it at 702,000 (Brown & Patten, 2013). The actual number of Hondurans in the U.S. is likely even greater, since many studies indicate that large numbers of immigrants have arrived illegally. The U.S. Department of State (DoS), for instance, estimated recently that about one million Hondurans live in the country, the majority (600,000) undocumented (USDoS, 2014b). This is in addition to a very large documented and undocumented Latino immigrant community present throughout the country, including in states geographically close to Canada. Many Canadian immigrants from Latin America therefore likely have networks that extend into the U.S. Canada also has a large undocumented immigrant population; although its size and composition is more opaque (estimates put it at around 100,000). The large pool of undocumented immigrants in the U.S., of which Hondurans are a significant proportion, inevitably produces onward undocumented migration to Canada.

The experience of Hondurans in Canada is not easily studied, given the relatively modest size and recent arrival of the community. Several factors have affected the flow of Central American immigrants to Canada generally. The first is the high level of political violence that triggered massive outflows of refugees during the 1970s and 1980s (Garcia, 2006a). This created large refugee populations both in the surrounding region and in the more stable countries to the north: Mexico, the U.S. and Canada. While Honduras was spared the civil conflicts that plunged Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala into violence, it was directly affected by large refugee flows from these countries, and by other conflicts in the region, and served as a base for U.S.-backed forces fighting the Nicaraguan revolutionary government. Although political violence has abated, civil and criminal violence remain very high throughout the region, contributing to ongoing migratory pressure. The country's deep and persistent poverty constitutes another key push factor, and remittances are critical to the livelihood of many Hondurans.

The latest chapter in the history of migration from Central to North America is the recent arrival of huge numbers of unaccompanied children to the U.S., making the long trek by land from their countries to the U.S. border. This surge in these so-called “unaccompanied alien children” is a consequence of the multiple crises that have affected the region over several decades, particularly the emergence of powerful transnational gangs that specifically target children for recruitment and exploitation (Muggah, 2014). Honduras is among the countries most affected by this crisis, which is bound to have an impact on the already growing migration of Hondurans to Canada.

| Year |

Canada |

U.S. |

Mexico |

|---|---|---|---|

2004 |

159 |

9,397 |

64,952 |

2005 |

181 |

18,941 |

64,144 |

2006 |

105 |

24,643 |

55,843 |

2007 |

75 |

29,348 |

38,833 |

2008 |

111 |

30,018 |

27,067 |

2009 |

174 |

25,101 |

23,529 |

2010 |

190 |

22,878 |

23,307 |

2011 |

201 |

22,448 |

18,279 |

2012 |

208* |

32,340 |

27,663 |

2013 |

162* |

38,080 |

34,599 |

2014 |

97* |

36,427 |

44,590 |

Source: El Heraldo 2014; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) 2015, 18, *data provided by CBSA. |

|||

To give a sense of Canada's place within the broader scheme of deportation to Honduras, it is useful to compare figures of deportees from Canada with the much larger numbers deported from the U.S. and Mexico. As Table 1 shows, deportations from Canada in recent years have never constituted more than 0.5 percent of those from the U.S. and Mexico combined.

According to the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), 2,305 Hondurans were removed from Canada between 1997 and 2014. Of these deportees, the majority were removed for non-compliance with the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, 2001 (IRPA) (1,524), or problems with their visa (253). Only 301 of the 2,305 were removed for reasons of criminality. CBSA statistics provide some background on the kinds of criminal acts that Hondurans deported from Canada have committed. Table 2 outlines the specific criminal conviction that led to the deportation of Honduran nationals in 2012 and 2013. As the table shows, a significant proportion of criminal deportees from Honduras are involved in drug importation, trafficking or possession.

| Conviction |

Number |

|---|---|

Assault (including causing bodily harm) |

15 |

Assault with a weapon |

5 |

Sexual assault/rape/interference |

5 |

Uttering threats |

4 |

Possession of a weapon/firearm |

3 |

Break, enter, theft/burglary/robbery |

10 |

Drug importation |

2 |

Drug trafficking |

37 |

Drug possession |

16 |

Personation/fraudulent document/misrepresentation |

2 |

Other |

33 |

Source: Statistics provided by CBSA, November 2015. |

|

According to the CBSA, among those Hondurans deported for drug trafficking offences in 2012 and 2013, 16 were involved in cocaine, 3 were involved in heroin, 2 were involved in marijuana/hashish, and 24 were involved in an unknown substance. Only one deportee in 2012 and 2013 was proven to be associated with a specific Honduran gang, in this case, MS-13. For the period 2005–2014, a total of 26 Hondurans were removed from Canada for involvement in organized crime, as defined by the IRPA.

One of the most high-profile recent gang-related incidents in Canada involved Honduran immigrants: the police killing of Freddy Alberto Villanueva in 2008, and the attempted deportation of his brother Dany. Both were suspected of gang activity, and the shooting of Freddy led to accusations of police violence and triggered riots in Montreal, where thousands of Latin Americans live, many in impoverished neighbourhoods. The incident was taken up by organizations that monitor police violence, and the attempted deportation of Dany Villanueva became a focus of attention for various human rights groups (Popovic, 2011). In 2014, Dany was granted a pre-removal risk assessment, which in effect suspended his deportation, after he argued that his life would be in danger if he were forced to return to Honduras (Montreal Gazette, 2014).

The Experience of Deportees in Honduras

Honduras features abysmal levels of human development (ranking 129th of 187 in the United Nations Development Programme's [UNDP's] 2014 Human Development Index). Nearly half of Hondurans live in extreme deprivation, defined as lacking the most basic means to feed themselves (Casas-Zamora, 2015:2). Regionally, about a quarter of young people are neither studying nor working, have no real stake in their societies, and find it hard to resist the pull of gangs and other forms of criminality (Casas-Zamora, 2015:9). Deportees face even bleaker prospects, since, as the director of the Centro de Atención al Migrante Retornado (CAMR), told the authors in an interview, “Honduran society still rejects the Hondurans that are deported, thinking that they are criminals.”Note 2 The Honduran government has acknowledged the country's inability to absorb the large numbers of deportees (Meyer, 2015:17). Deportees may also be targeted by elements in the security forces. A researcher of San Diego State University has found evidence that those deported on criminal grounds are sometimes persecuted by the state: “Several times the police have handed over a deportee who had a criminal record to an opposing gang. It doesn't seem to be systematic, but a few cases have come up where the police handed over people who had very minor crimes [on their record], as well as a few former gang members.”Note 3

Facing significant risks of gang victimization, racketeering, poverty and other violence, criminal deportees may be forced to join gangs in order to survive. Indeed, many Hondurans who migrate to flee gang violence and forcible recruitment may face these threats upon their return. A researcher of San Diego State University has documented 35 cases of migrants killed after being deported from the U.S. (Brodzinsky & Pilkington, 2015). Although gang membership may provide economic opportunity and social support, it exposes members to a series of additional dangers, including inter-gang violence, brutal state crackdowns and vigilante-style social cleansing campaigns. Deportation may continue to feed Central America's gang problem. As one researcher noted, “evidence shows that criminals returning from the U.S. to Mexico and countries in Central America have been a major catalyst for violence and crime in the region” (Garzón, 2013:5). While the number of deportees it sends is relatively low, Canada is nonetheless contributing to this trend.

The problems facing deported migrants have caused many deportees to attempt to migrate once more. In a UNHCR study, of those who cited violence as their reason for migrating, 44 percent said they had concrete plans to migrate again, compared to 36 percent of those who migrated for other reasons (UNHCR, 2015:36). However, it is worth noting that this is likely an underestimation, as many simply may not wish to report their plans. A Latin America researcher interviewed for this report blamed the large numbers of repeat migrations on a lack of support services in Honduras, stating that: “Migrants have little to no support and therefore, with conditions remaining the same, have no reason not to leave again.”Note 4 In particular, those who had lived for many years in the U.S. before being deported generally try to return soon after.

According to the official of CAMR, “it is rare for a person who has lived a long time in the U.S. to live here again…They return immediately to the border, to continue their route to the U.S.”Note 5 Those deported from the U.S. are likely to make a repeated attempt to flee the poverty and violence that originally pushed them northward. All those consulted in Honduras agreed that most deported migrants would plan to migrate again. According to a legal advisor at CAMR, several trips are included in the migrant smugglers' fee: “They pay [smugglers] a certain amount of money to get to the U.S., and from what I understand they get three journeys—so if they are caught the first time, they have another two chances.”Note 6

Interviews with Honduran officials and deportees indicated that the likelihood of return migration for Hondurans deported from Canada might be significantly lower. There were 2,305 Honduran nationals deported from Canada between 1997 and 2014, for both criminal and non-criminal reasons, representing an average of approximately 128 per year. According to CBSA statistics, in 2012 and 2013, 33 deportees attempted to return to Canada. Of these, 20 attempted to return once and 13 attempted to return between two and five times. In the U.S., by contrast, “out of the 188,382 criminal aliens deported in 2011, at least 86,699, or 46 percent, had been deported earlier and had illegally returned to the United States” (Schulkin, 2012:2). These relatively low Canadian numbers reinforce the notion shared in an interview with a Honduran law enforcement official that those deported from Canada generally see return as too difficult, and the border controls too tight, to merit the attempt (and may attempt to migrate to the U.S. instead).Note 7 While there are established overland routes from Central America through Mexico and into the U.S. that are well-known to Hondurans, there is no comparable route to Canada.

The Reintegration Capacity of Honduras

While there are some (grossly insufficient and under-resourced) reintegration programs for returned migrants deported for violation of visa conditions and the like, there are no programs tailored to criminal deportees. Experts interviewed for this report indicated that “in a country like Honduras, there is no infrastructure, institutional or otherwise, to allow for return migrants to reintegrate in a meaningful way into Honduran society.”Note 8 Seelke (2014:8) indicates that support services to deportees vary widely across Latin America: “While a few large and relatively wealthy countries (such as Colombia and Mexico) have established comprehensive deportee reintegration assistance programs, most countries provide few, if any, services to returning deportees. In Central America, for example, the few programs that do exist tend to be funded and administered by either the Catholic Church, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), or the International Organization for Migration (IOM).” As one researcher told the authors, the return centres are not government operated. CAMR uses government spaces and receives funding from the government, but is not actually part of the government.Note 9

In Honduras, CAMR, the Asociación Menonita and other organizations helping returned migrants receive much of their funding from religious bodies.Note 10 Even with funding from these religious organizations and from the Honduran and U.S. governments, CAMR is under-resourced. As one Latin American researcher interviewed for this report noted: “At CAMR they do what they can with very few resources, but there is no real buy-in from the Honduran Government—the few programs that are in place are not adequate and don't benefit most people. Those who have fled violence are offered no protection whatsoever.”Note 11

Transnational Crime Connections between Canada and Honduras

Honduras hosts two distinct forms of transnational criminality that could affect public security in Canada: the youth gangs known as the maras, and the more sophisticated transnational organized crime groups that oversee the hemisphere's drug trade (while also participating in other forms of transnational organized crime including human smuggling and arms trafficking). A crucial distinction must be made between these types of criminal groups owing to their very different natures: the maras are loose networks of highly localized, place-based identity groups, while the organized crime networks utilize a much more sophisticated modus operandi that features high-level corruption, extensive rural landholdings and clandestine flights. There is some ad hoc collaboration between these two types of criminal organization, and gangs do indeed represent a subset of organized crime that often meets Canada's Criminal Code definition of a criminal organization (MacKenzie, 2012:6); yet these two types of criminality remain fundamentally distinct phenomena and are thus considered separately below. As the following section explains, to date there is no evidence of direct ties to Canada from either type of Honduran criminal organization, and criminal deportees are highly unlikely to forge such connections in the future.

The Origins and Evolution of the Central American MarasNote 12

Honduras is host to over 100 street gangs of varying natures (Bosworth, 2011:70), but the groups most feared for their reputed transnational reach are the maras, which represent the paradigmatic case of circular migration fuelling crime. Given their known reach into North America, these gangs provide a possible channel by which Honduran deportees from Canada could become threats to Canada. This section examines the origins, activities and evolution of the Central American maras, while the next section assesses their links to Canada. Together they find that the “transnational” structure of the maras is often overstated, and the risk of criminal deportees aiding mara activity in Canada is negligible. While these groups pose a significant threat in the U.S., the situation in Canada is very different.

The maras originated in the 1980s, when thousands of Guatemalans and Salvadorans fled the civil wars in their countries and migrated to poor areas of Los Angeles. Their children suffered poverty, gang victimization and social exclusion, and some coped with their situation by joining gangs—either the 18th Street Gang (also known as the Dieciocho, Barrio 18,or M-18, formed in the 1960s by marginalized Mexican youths), or the rival Mara Salvatrucha or MS-13 (formed by Central Americans). Escalating gang violence and growing undocumented immigration prompted the Clinton Administration to pass the Illegal Immigrant Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act in 1996, which sent thousands of these young gang members “back” to Central American societies they scarcely knew. Between 1998 and 2005, the U.S. deported 46,000 convicts and 160,000 undocumented immigrants to Central America (Rodgers, Muggah & Stevenson, 2009:7) and it continues to deport criminals by the thousands.Note 13

As some of the poorest countries in the world, still reeling from war and free-market “structural adjustment” reforms, the Central American republics were (and remain) entirely unable to reintegrate deportees into society (and were generally not forewarned of their arrival). Deportees entered urban environments already host to a multitude of street gangs fuelled by social marginalization, poverty, a lack of basic services and education, unemployment, public insecurity, dysfunctional families, rapid urbanization, and a culture of violence and machismo. Lacking support networks, cultural orientation, and, in some cases, Spanish language proficiency, many of these “returnees” relied on their Barrio 18 or MS-13 gang identities in order to survive. The two maras quickly came to dominate the gang landscape as local groups joined either the Barrio 18 or MS-13 franchise. While most Los Angeles gang members were deported to El Salvador and Guatemala, their mara brands crossed the border to dominate in Honduras as well.

The maras are composed of local “cliques” of 30–150 members, bolstered by a multitude of local supporters and tied to a specific neighbourhood.Note 14 Each clique is led by the primera palabra and the segunda palabra (the first and second bosses, or “givers of the word”) and remain generally autonomous in their operations, relating to other cliques on an ad hoc basis.Note 15 They are not arranged into a hierarchy of command and control, but associate informally in shifting arrangements depending on their reputation, fealty and experience. The cliques are generally involved in localized crime, including neighbourhood drug distribution, protection rackets, extortion, kidnapping, robbery and murder. The maras provide a modicum of order to some marginalized neighbourhoods, using acts of demonstrative violence to maintain their authority and enforce obedience.

Estimates of the number of gang members in Honduras vary widely. One high-level U.S. State Department official estimated there to be as many as 85,000 mara members in the Northern Triangle (Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras) today (Seelke, 2014:3), but this is a relatively high estimate. In Honduras, estimates range from 36,000, in a United States Agency for International Development (USAID) report (USAID, 2006), to 25,000, from the Honduran police (InSight Crime and the Asociación para una Sociedad más Justa, 2015:7), to a total of 12,000 from the UNODC (2012:27-28), which estimates that Honduras hosts 7,000 MS-13 members and 5,000 Barrio 18 members, to even lower estimates by Honduran NGOs, which put the number at 6,000 or less (InSight Crime and the Asociación para una Sociedad más Justa, 2015:7). By 2012 figures, Honduras hosted 149 mareros per 100,000 population; Guatemala hosted 153 per 100,000 and El Salvador 323 (UNODC, 2012:29).

As the maras rapidly spread across the region, the governments of Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador responded in the early 2000s with a series of mano dura (iron fist) enforcement-first policies that combine militarized crackdowns with draconian penal and judicial measures. El Salvador led the charge with its July 2003 legislation enabling authorities to arrest and imprison youth for up to five years for having gang tattoos or using gang signals. Honduras followed with its August 2003 cero tolerancia policy that outlawed mara membership, with punishments of up to 12—and later 30—years in prison. Within a year, the prison population rose to twice the capacity of its facilities and suffered large-scale rioting (Arana, 2005:102). Following violent conflagrations between Barrio 18 and MS-13 prisoners, the two maras were segregated into separate wings and prisons. In July 2015, the Honduran Congress voted to further stiffen penalties for mara members, extending the maximum prison terms for gang leaders from 30 to 50 years and for lower members from 20 to 30 years (Dhont, 2015). Today, the country's 24 prisons and 3 preventive detention centres house 14,531 people in facilities designed for just 8,130 (US DoS, 2014a:4).Note 16

Ultimately, these mano dura policies have only exacerbated the violence and criminality of the maras by stimulating the evolution of gang behaviours. While criminal deportation from the U.S. represented a “first transition” in the nature of the maras (their spread to Central America), the mano dura policies fostered a “second transition” to greater levels of organizational capacity, violence and criminality (Santamaría, 2013). In Honduras, the mano dura policies of the early 2000s temporarily forced the maras out of Tegucigalpa, and prompted their spread to other Honduran cities. Mareros quickly learned to be less conspicuous in their appearance and behaviour. They also, on many occasions, retaliated against state policies with acts of extreme violence against civilians, including an incident in which MS-13 members opened machine gun fire on a bus in Chamalecon, killing 28 people at random to protest the government's crackdown on gangs (Arana, 2005:98). The country's homicide rates continued to rise after the government crackdown in the early 2000s.

Most importantly, the massive arrests stemming from mano dura policies have turned prisons into important sites of gang coordination, training and recruitment. Shielded from law enforcement, rivals and day-to-day responsibilities, imprisoned mara leaders can meet and coordinate criminal activities that take place outside the prison, using cell phones and corrupt prison officials.Note 17 The mano dura policies fostered a war mentality and defensive posture for the maras, and imprisoned leaders gained the contacts and forged the cooperation necessary to deepen their involvement in the drug and arms trade and coordinate more sophisticated extortion, kidnapping and targeted killing operations (Santamaría, 2013:74-75).

In this way, the mano dura had the perverse effect of increasing the organization, violence and criminality of the maras. Nonetheless, these policies remain popular among Central American publics and politicians; the maras provide a convenient scapegoat for the multiple forms of violence and criminality afflicting the country (including high-level corruption) and the mano dura encourages a “populism of fear” based on punitive measures that undermine human rights and the rule of law (Godoy, 2005). Meanwhile, “second generation” gang policies (sometimes called the mano amiga or the mano extendida—the “friendly hand” or the “extended hand”), which address the causes of gang membership and aim to rehabilitate and reintegrate gang members (in contrast to the enforcement-first approach of the first generation mano dura policies), have so far been ad hoc, sorely underfunded and shown little concrete result (Jütersonke, Muggah & Rodgers, 2009:385–391).

The second transition arguably fostered greater hierarchy and transnational reach of the maras, but both qualities are easily exaggerated. After consolidating their dominance in Central America, the maras continued their spread by establishing cliques in Mexico, many American cities, and even Canada. In October 2012, the U.S. Department of the Treasury labeled MS-13 a “transnational criminal organization” in the first ever application of the category to a U.S. street gang (Executive Order 13581). This spread, however, “should not be mistaken for evidence that they operate transnationally, or that they all respond to some international chain of command” (UNODC, 2012:28). The expert consensus is that “neither gang is a real federal structure, much less a transnational one. Neither the Dieciocho nor the Salvatrucha gangs answer to a single chain of command, and their “umbrella” nature is more symbolic of a particular historical origin than demonstrative of any real unity, be it of leadership or action” (Jütersonke, Muggah & Rodgers, 2009:380). To the extent that cross-border links exist between cliques, they are mainly of mutual recognition of identity rather than institutionalized coordination and collaboration in transnational criminal activity.Note 18

The maras are first and foremost local, place-based identity groups.Note 19 As the UNODC (2012:27) asserts, the maras' “territorial control is about identity, about ‘respect,' and about their place in the world.” Wolf (2012:77) contends that “crime is a product of gang affiliation rather than its purpose. Gangs exist because they fulfill their members' psychosocial aspirations (notably status, identity, respect, friendship, and fun) and legitimate antisocial behavior.” Alarmist fears of their involvement in transnational flows of drugs, migrants, and other organized criminality are generally unwarranted.Note 20 The MS-13 has become involved in migrant-smuggling over the Guatemalan-Mexican border, but as a gatekeeping protection racket rather than as transporters. The maras have also been known to work with the Zetas and Sinaloa Federation (Mexican transnational drug trafficking organizations), but only on an ad hoc and local basis, providing security for shipments, distributing drugs locally and carrying out executions (see Corcoran, 2011). The maras are simply incapable of operating their own transnational criminal enterprise. Ultimately, they“play very little role in transnational cocaine smuggling” (UNODC, 2012:5), and their conspicuous, undisciplined, and violent natures render them unattractive partners for transnational organized crime groups.Note 21

Although the maras have gradually become more coordinated and hierarchical, their structure nonetheless remains loose and fluid. Hierarchy, to the extent that it exists, is most advanced in El Salvador where the negotiation and implementation of a 2012 gang truce—in which the MS-13 and Barrio 18 agreed to stop killings of rival gang members and members of the security forces in exchange for concessions from the authorities—required such arrangements, including city-wide mara leadership. The absence of such coordination, and the lack of official sanction for such a step, prevented a replication of the truce in Honduras. Indeed, the maras in Honduras are generally believed to be weaker and less organized than their counterparts in El Salvador and Guatemala.Note 22

Notably, some foresee a “third transition” in the evolution of the maras, one in which theybegin to disappear as the attraction of more organized forms of criminality (such as those discussed below) replace their logic of identity, rivalry and belonging (Santamaría, 2013:75-76). Already, more experienced gang members may be entering sophisticated transnational organized crime networks, but on an individual basis rather than through their mara affiliation. One report noted a decline of neighbourhood gangs alongside the rise of larger organized crime groups: “As the drug trade has generated new opportunities for economic gain, violent crime appears to be driven less by turf battles linked to gang identity. Homicides have evolved from visible gang violence to hired killings with unknown motives and perpetrators. The local sale and consumption of drugs have increased substantially, while a wide range of economic crimes, from extortion to assault and robbery, has become more common” (Berg & Carranza, 2015:13). The extent and future of this possible “third transition,” however, remain uncertain.

The Central American Maras and Canada

Canadian law enforcement authorities have since 2006 identified an increasing number of gangs operating in Canada (Criminal Intelligence Service of Canada [CISC], 2010:18),Note 23 predominantly engaged in local distribution of illicit drugs that they obtain from more sophisticated organized crime groups, including outlaw motorcycle gangs, Italian mafia groups and Asian criminal organizations (Barker, 2012:50). In Toronto, for example, police have identified over 70 gangs, ranging in size from 10 to 40 members and encompassing 1,800–2,000 members in total, typically aged between 16 and 25 (National Post, n.d.). Canadian street gangs generally lack the sophistication required to import or produce large quantities of illicit drugs (CISC, 2010:20). As the CISC (2010: 20) reports, “The vast majority of street gangs operate at a local level with limited reach or mobility beyond a defined area of operation. A small number of street gangs extend their illicit activities at a provincial level as well as inter-provincially. Some street gangs in Canada have borrowed or copied the name of well-known international gangs, such as the U.S. ‘Crips' or ‘Bloods', but no known international affiliation actually exists.”

There is to date no evidence of a direct connection between Honduran deportees from Canada and gang activity in Canada. Indeed, the influence of deportees within Central American mara cliques has waned substantially in recent years as these groups have expanded their local roots (Wolf, 2012:75). Such ties remain possible, in the present and in the future, because the MS-13 and the Barrio 18 are both known to operate in Canada, but are highly improbable given the nature of the maras, asoutlined above.Note 24 Authorities believe that mareros from Central America seek refuge in Canada (CTV News, 2008), particularly gang members from Guatemala (Mason, 2008). Yet the diffused and localized structure of these gangs belies the purported transnational connections by which deportees in Honduras could influence gang activity in Canada.

The exact size of mara groups is difficult to estimate and little data is available from the academic literature.Note 25 Nonetheless, both the Barrio 18 and MS-13 operate in Canada and present significant risks to public security. The MS-13 spread from Seattle into Vancouver, where police arrested the first member in 1997, and the numbers of suspected gang members and drug houses raided have both increased since then (Global National, 2007). It was reported in 2007 that the gang had 34 members in Vancouver (The Gazette, 2007). There is one publicized instance of an MS-13 member illegally entering Canada from Seattle and being deported several times (Bolan, 2009), yet this case suggests that any cross-border mara ties would likely be between Canadian and American cliques, not with Honduran ones. There are nonetheless some concerns about gang members entering Canada with, and taking advantage of, migrant workers (Global National, 2007).

In June 2008, a Greater Toronto Area-wide police operation raided 22 homes in the city and its outlying regions to arrest 21 suspected members of the MS-13, alleged to be involved in drug and arms trafficking and violent robberies. Police seized more than six kilos of cocaine, drug paraphernalia, firearms and other illegal weapons, vehicles and cash. They portrayed the operation as an attempt to prevent the still nascent mara from developing a foothold in Canada (Henry, 2008a). As then-Toronto Police Chief Bill Blair said of the raid, “We have dismantled this clique by cutting off its head” (Howley, 2008). Authorities laid 63 charges against 14 men and 3 women ranging from 19 to 46 years of age (Henry, 2008b). Four of those arrested were young Latino immigrants charged with conspiracy to commit murder against a corrections official, but these charges were later stayed (Howley, 2008; Henry, 2008c). Blair declared: “We believe with the arrest we have effectively ended the activities of this gang” (CTV News, 2008), and indeed the group has been largely absent from news coverage since the 2008 raid. Yet the MS-13 has a known presence in Vancouver, Montreal, Toronto and, to a lesser extent, Edmonton and Calgary (Global National, 2007). Ethnically based gangs of Hispanic origin are most prominent in Quebec (Barker, 2012:53), but there is no evidence of specifically Honduran gangs, or involvement of deportees.

In Canada, the mara is not known to commit the type of brutal acts of violence for which it is known in the U.S. Indeed, cliques in different countries tend to have distinct profiles. An FBI threat assessment concerning the MS-13 found them to operate in at least 42 states and the District of Columbia, with 6,000–10,000 members in the U.S., and an expanding affiliation, but no national leadership structure (US FBI, 2008). Their Canadian numbers are orders of magnitude less than in the U.S. and Central America. Canadian authorities have liaised with counterparts in these countries to prevent mara growth. There is no evidence that mara groups in Canada have links with cliques in Honduras, and the diffuse structure of the maras makes the future development of such connections highly unlikely.

Organized Crime in Honduras

Honduras occupies the midway transshipment point along the “highest value drug flow in the world” (UNODC, 2012:16). It links the world's most prolific cocaine producers in South America to the world's largest drug market in the U.S. This role is hardly a new one; in the 1980s, for example, Honduras was home to the infamous drug trafficker Juan Ramón Matta Ballesteros, who used the country to transit cocaine from Pablo Escobar's Medellin Cartel to Mexico's still nascent Guadalajara Cartel (later to transform into the Sinaloa Federation). Yet the presence—and violence—of organized crime in Honduras (and Central America more broadly) has expanded precipitously in recent years owing to developments elsewhere.

When successful interdiction efforts closed Caribbean trafficking routes in the 1990s, drug flows shifted to Central American pathways into North America. This relocation, alongside Colombia's crackdown on its largest drug trafficking organizations (DTOs), has increasingly empowered Mexican operations over Colombian ones. Their growing power prompted the Mexican government to launch a full military assault against the country's DTOs, escalating the violence among these groups as they fight over a declining cocaine market (UNODC, 2012:17–20). Mexican DTOs responded to the pressure in Mexico by moving their operations—and the accompanying violence—further south into Central America.

The June 2009 military coup against Honduran President Manuel Zelaya enabled the Mexican DTOs to consolidate their hold on Honduras (Bosworth, 2011; Ruhl, 2012). With the government in turmoil, security forces focused on the political crisis, American military assistance suspended and diplomatic ties broken, organized crime flourished in Honduras. “The result was a kind of cocaine gold rush. Direct flights from the Venezuelan/Colombian border to airstrips in Honduras skyrocketed, and a violent struggle began for control of this revivified drug artery” (UNODC, 2012:19). In 2009, an estimated 200 metric tons of narcotics passed through Honduras (Dudley, 2011a:30); in 2010, the figure was 267 tons (UNODC, 2012:43). In September 2010, shortly after the coup, the U.S. designated Honduras a major drug transit country.

Honduras today hosts the Zetas, Gulfand Sinaloa Federation DTOs of Mexico, which work with a loose network of local transportistas. The latter boast long-standing expertise in smuggling contraband, control key trafficking territories and secure the cooperation of corrupt officials. These local networks are loose and flexible, so there is often overlap in areas of operation rather than different organizations carving out exclusive territories. Police have reported Sinaloan operations in the provinces of Copán, Santa Bárbara, Colón, Olancho and Gracias a Dios (Bosworth, 2011:65), often buying up land and co-opting local officials along the Honduras-Guatemalan border (Dudley, 2011a:31). The Zetas are known to operate in Olancho and Cortés (Dudley, 2011a:31). Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzman, the head of the Sinaloa Federation who recently escaped for the second time from a Mexican maximum security prison, has been rumoured to reside in Honduras at various times (Bosworth, 2011:65).

Most cocaine arrives by boat to the Atlantic coast, but drug flights have grown considerably following the 2009 coup, utilizing hundreds of clandestine airstrips in Yoro and Olancho provinces as well as farmlands specifically rented for landings (Dudley, 2011a:38–40). The Sinaloa and Gulf DTOs tend to move cocaine by land over the Honduras-Guatemalan border, while the Zetas favour sea transportation to either Guatemala or Mexico, departing from the vicinity of La Ceiba (Bosworth, 2011:64). As Bosworth (2011: 63) asserts: “Honduras is often the location where the handoff is made, but a large Mexican criminal organization controls the cocaine trafficking from Honduras to Mexico, across the border into the United States, and increasingly the distribution inside the United States.”

Much of the violence afflicting Honduras today arises from the destabilization of local criminal arrangements and power balances triggered by the Mexican expansion in Honduras. The UNODC (2012:11) identifies “a clear link between contested trafficking areas and the murder rate.” As a result, the border between Guatemala and Honduras is today one of the most dangerous places in the world. The International Crisis Group (ICG) (2014:i) reports that “The absence of effective law enforcement has allowed wealthy traffickers to become de facto authorities in some areas, dispensing jobs and humanitarian assistance but also intimidating and corrupting local officials. Increasing competition over routes and the arrest or killing of top traffickers has splintered some criminal groups, empowering new, often more violent figures.”

The cocaine trade is hardly the only form of organized crime afflicting Honduras. The Sinaloa Federation has used the Olancho province to manufacture methamphetamine and ecstasy for American and European markets (Bosworth, 2011:64, 66). Arms smuggling is also prominent, and firearms (including grenade launchers) that have gone missing from Honduran armories have resurfaced in Mexico or Colombia (Bosworth, 2011:78). Human smuggling does occur, but because Central American citizens can move freely throughout the region, smuggling is mostly an issue at the Guatemalan border with Mexico.

The transportistas that facilitate transnational organized crime through Honduras have a profile that would scarcely place them in association with criminal deportees from Canada. They tend to be wealthy, established family-based operations that have specialized knowledge, important contacts with corrupt state officials and other Honduran elites, and access to large landholdings in key (and generally remote) transit areas. These features sharply distinguish tranportista networks from the maras and other lower-level criminals. The UNODC (2012:42) reports that “Some municipalities in the northwest part of the country (in Copán, Ocotepeque, Santa Bárbara) are completely under the control of complex networks of mayors, businessmen and landowners (“los señores”) dedicated to cocaine trafficking.” This profile describes the two best-known transportista groups in Honduras—the Cachiros and the Valles, which are family-based groups known to work with the Sinaloa Federation (InSight Crime, “Cachiros Profile” and “Valles Profile”). Key leaders of both groups have been arrested, undermining their future prospects, but other transportista networks are readily able to pick up the slack despite government successes against them. As Colombia and Mexico continue their offensives against organized crime, they may inadvertently displace it further into Central America in the coming years (Santamaría, 2013:83).

Over the past decade, Mexican DTOs have largely displaced Colombian groups in Honduras and gained dominance over domestic transportista groups to control the flow of drugs through Honduras (Bosworth, 2011:72). In turn, transportista groups may hire local gangs for specific tasks on an ad hoc basis, but gang members are unattractive partners (as discussed above). Given the nature of these transportista groups and the Mexican DTOs that dominate them, criminal deportees appear as even less likely candidates for recruitment into these transnational criminal networks.

Honduran Organized Crime and Canada

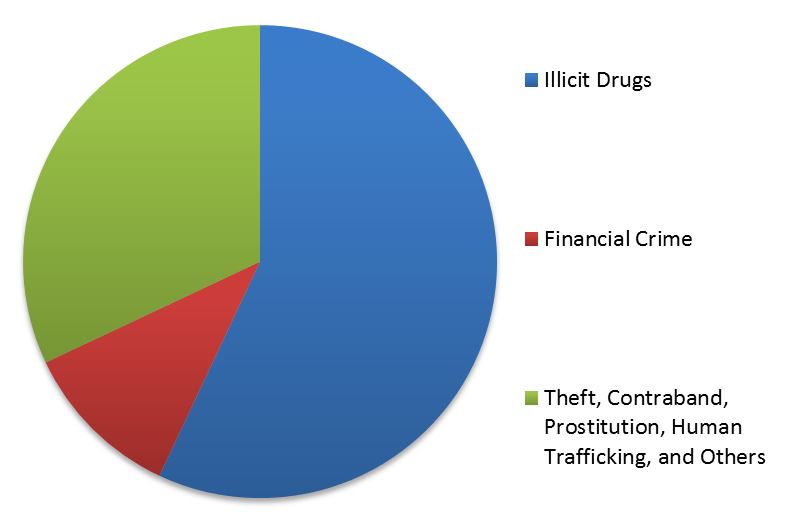

As a recent report of Canada's Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights (MacKenzie, 2012:2) asserts, “Organized crime poses a serious long-term threat to Canada's institutions, society, economy, and to our individual quality of life.” Key organized criminal markets in Canada include: counterfeit goods, illicit drugs and pharmaceuticals, firearms, mortgage fraud, payment card fraud, vehicle theft, heavy equipment theft, securities fraud, prostitution, illegal gambling, and smuggling of contraband goods (CISC, 2010). Eighty-three percent of Canadian organized crime groups are involved in the illicit drug trade, with cocaine as the predominant market, followed by cannabis, then synthetic drugs (MacKenzie, 2012:10). Organized criminals engage in such crimes as theft, robbery, murder, extortion, fraud, assault, intimidation, money laundering and financial offences.

Figure 1: Canadian Organized Criminal Markets

Based on figures in MacKenzie (2012:10-11)

Image description

Illicit Drugs: 55%

Financial Crime: 10%

Theft, Contraband, Prostitution, Human Trafficking, and Others: 30%

In place of the hierarchical, competitive, and ethnic or familial organized crime groups of the past, authorities today increasingly identify more diffuse and fluid networks (CISC, 2010:12; Beare, 2015; MacKenzie, 2012:23-24). There is no dominant organized crime group, but a fluctuating diversity of 600 to 900 groups across the country, with major hubs in Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal. These groups include: “not only tightly knit groups comprised of individuals with familial, ethno-geographic or cultural ties, but also more loosely associated, ethnically diverse, integrated criminal networks” (CISC, 2010:23).

There are no direct ties between Honduran organized criminal groups and Canada, and Honduran transportista groups do not generally operate outside of Central America.Note 26 But Honduras nonetheless occupies a crucial location in hemispheric patterns of transnational organized crime that affect Canada, most prominently via cocaine smuggled into the country where it feeds local criminality and jeopardizes the health of approximately 305,000 Canadian users (Health Canada, 2012).Note 27

The majority of cocaine entering Canada crosses the U.S. border in commercial and—to a lesser extent—personal vehicles. In the U.S., Mexican, Colombian and Dominican gangs control the cocaine market, selling to outlaw motorcycle gangs, traditional organized crime rings (of Italian origin), independent groups and Southeast Asian organized crime groups in Canada (U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) et al., 2010:6).Note 28 Mexican DTOs are known to move large quantities of cocaine through Chicago, some of which reaches Canada.Note 29 Cocaine transited by Mexican DTOs also fuels gang violence in Vancouver (Diebel, 2009).

Cocaine entering Canada thus does not relate directly to Honduran criminal groups, which operate much further down the supply chain. As one expert interviewed for this report noted, “there are many degrees of separation between people smuggling drugs into Canada and those transshipping it through Honduras. The relationship is really indirect.”Note 30 The knowledge and experiences of Canada gained by criminals deported to Honduras are thus very unlikely to assist these already well-established illicit flows into Canada. Honduran and other Latino demographics are not cited by authorities as significant players in the import and wholesale distribution of any drug in Canada (see US DHS et al., 2010).Note 31

Security and Judicial Capacity in Honduras

Deportees to Honduras are returning to an environment marked by some of the weakest state institutions and most brutal violence in the world. The Pentagon has recently deemed the Northern Triangle the “most dangerous non-war zone in the world” (Mulrine, 2011). Honduras in particular has suffered some of the highest murder rates “on record in modern times,” reaching a staggering 92 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2011 (UNODC, 2012:15). In 2012, Honduras had the second-highest rate of violent death in the world (Syria is highest) with approximately 90 violent deaths per 100,000 population (Geneva Declaration, 2015:58, 66). In 2011, San Pedro Sula became the world's most violent city, with a murder rate of 159 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants (International Security Sector Advisory Team [ISSAT] 2015), which rose to 193 per 100,000 in 2013 (ICG, 2014:3). The UNDP estimates that crime and violence costs Honduras the equivalent of 10.5 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) each year (Meyer, 2015:8).

One report (Berg & Carranza, 2015:6) attributes the growth in crime over the last decade to “several risk factors that have worsened during this period, including poverty, unemployment, urban migration, and shifts in the transnational drug trade, along with a political crisis that weakened the capacity of the state to respond.” In the 2015 Latinobarómetro survey of Honduras, 37.4 percent of respondents reported feeling that their security was “not guaranteed” against crime, 21.8 percent reported “little guaranteed,” and just 33.6 percent reported “somewhat guaranteed” or “very much guaranteed.” In 2014, one-third of Hondurans reported feeling “somewhat unsafe” or “very unsafe” in their own neighbourhoods, while 18.3 percent reported being victims of crime (Pérez & Zechmeister, 2015:163, 169).

As these figures suggest, the escalation of violence and criminality afflicting Honduras has readily overwhelmed its already fragile state institutions. Government agencies suffer endemic corruption and lack full control of Honduran territory, including its violent border with Guatemala, its long Caribbean coastline and large tracts of uninhabited land well suited to illicit activity. In Transparency International's 2014 Corruption Perceptions Index, the country ranked 126th out of 174. In 2014, 23 percent of Hondurans reported being asked for a bribe sometime in the previous year (Casas-Zamora, 2015, referring to data from the Latin American Public Opinion Project at Vanderbilt University). Widespread crime, the 2009 coup d'état, and poor governance are undermining the public's support for democratic politics (Ruhl, 2012:37; Meyer, 2015:1; Pérez & Zechmeister, 2015:191).

According to regional expert Steven Dudley (2011b:902), Co-director and Co-founder of InSight Crime, “Honduras is arguably at the greatest risk of turning into a narco-state, a government whose national interests are completely subsumed by those of the various competing criminal organizations such as the Sinaloa Cartel, the Zetas, local drug trafficking groups, or a combination.” The US DoS's 2014 Human Rights Report on Honduras found that “Among the most serious human rights problems were corruption, intimidation, and institutional weakness of the justice system leading to widespread impunity; unlawful and arbitrary killings by security forces; and harsh and at times life-threatening prison conditions” (2014:1).

Although homicide rates have dropped over the last two years and the Honduran government has arrested and extradited several prominent organized crime figures, the challenge of violent organized crime remains grave. Honduran government institutions are unable—and in many cases unwilling—to ensure the public safety of citizens (including deportees) and address the country's role in the transnational organized crime afflicting the hemisphere (see Meyer, 2015). International assistance has had limited success due to the dearth of reliable local partners and widespread institutional dysfunction. The following paragraphs provide an overview of the nature of the security and justice sectors in order to elucidate the institutional context to which deportees return and in which organized crime continues to thrive.

Honduran judicial institutions are known for their vulnerability to political interference from the executive branch and Congress, as well as their corruption and lack of capacity. Investigative capacity is particularly weak, and prosecutions selective, fostering massive impunity across the country. Lawyers and prosecutors are often targeted by organized crime, with at least 84 lawyers killed since 2010 (Gurney, 2014). Of the homicides recorded between 2010 and 2013, only four percent saw convictions (Meyer, 2015:9). According to 2015 Latinobarómetro results, 42.5 percent of Hondurans assess the performance of the judiciary as “poor” or “very poor,” while only 22.1 percent of Hondurans reported “some” or “much” confidence in the judiciary, 25.7 percent “little,” and 46.7 percent “none.”

As of 2011, the police force had just 14,491 officers (ISSAT 2015). With a population of 8.75 million, the country has approximately 166 officers per 100 000 people. Canada in 2014, for comparison, had 194 officers per 100 000 population, and the US had 234 in the same year.Note 32 In addition to being understaffed, it is also one of the most corrupt bodies in the region, known to demand bribes, use excessive force, provide information to criminal groups, allow drugs to pass unchecked and participate in criminal violence (ISSAT 2015; Pérez & Zechmeister, 2015:175). The typical officer is poorly trained, underequipped and underpaid; they can make the equivalent of their USD 500 monthly salary in just a night's work for organized criminal operations (Ruhl, 2012:38-39). “The second highest ranking member of the Honduran National Congress recently estimated that 40 percent of the police are linked to organized crime” (Ruhl, 2012:39). In 2014, 41.4 percent of Hondurans reported they were either “dissatisfied” or “very dissatisfied” with police performance in their neighbourhood (Pérez & Zechmeister, 2015:176); and in 2015, Latinobarómetro surveys found 36.8 percent of Hondurans had “some” or “much” confidence in the police, while 29.7 percent had “little” and 32.7 percent had “none.”

The Honduran government is trying to reform the police force by rooting out corruption. In 2011, it created the Directorate for the Investigation and Evaluation of the Police, an external oversight agency, and in 2012 it formed a Commission on Public Security Reform, but resources are scarce. A purge of corrupt officers using polygraphs and financial monitoring is underway, but progress remains slow and partial. In perhaps the most promising step forward, the country began a community policing initiative in September 2011 that includes 250 officers and 50,000 civilian volunteers that has shown some positive results in reducing crime in neighbourhoods of Tegucigalpa (ISSAT 2015; for more on community-based crime prevention, see Berg & Carranza, 2015). The U.S. is a major supporter of Honduran police reform, establishing a Criminal Investigative School, leading (via the FBI) a Transnational Anti-Gang Unit, supporting a Violent Crimes Task Force, and (via USAID) implementing community-based crime and violence prevention programs (Meyer, 2015:18).

Given the low force levels, the corruption and the incapacity of the Honduran police force, the government has increasingly relied upon its armed forces to fight the country's mounting insecurity.Note 33 The military has 10,550 personnel, mostly concentrated in ground forces, who are constitutionally permitted to cooperate with public security institutions to combat drug trafficking, arms trafficking and terrorism (ISSAT, 2015). A November 2011 emergency decree (subsequently renewed) granted the military policing powers, while a 2012 bill created a new elite military police force to fight organized crime. By such decrees, military units have gained the power to collect evidence, conduct searches and arrest suspects despite their lack of training in law enforcement (Ruhl, 2012:40). The Honduran Congress also established the “Tigers,” an elite military-trained unit of the National Police. The current government continues the widespread use of the military against crime, deploying 2,000 military police to San Pedro Sula in March 2014. The public's confidence in the armed forces is much greater than its confidence in the police. According to 2015 Latinobarómetro results, 49.5 percent of Honduras had “some” or “much” confidence in the armed forces, versus 25.7 percent with “little” and 22.7 percent with “none.”

Although the military is popular in the fight against crime, its deployment raises a number of issues concerning human rights, the rule of law and the militarization of society. The lack of separation between the military and the police has long undermined public security, human rights and democracy throughout Latin America (Withers, Santos & Isacson, 2010). The military ruled the country almost uninterrupted from 1963 to 1982, and the Honduran police force was under military control until 1996; its status as a democratic civilian institution remains embryonic and vulnerable. Further, the armed forces may itself have ties to organized crime, as thousands of guns have disappeared from government stockpiles, which, combined with the country's lax gun laws, render the country a major source for the regional arms trade (ISSAT, 2015).

It must also be recalled that it was the military that perpetrated the 2009 coup d'état against President Manuel Zelaya, comprising a major affront to constitutional order and the rule of law in the country. As Human Rights Watch (2010:1) reports: “After the coup, security forces committed serious human rights violations, killing some protesters, repeatedly using excessive force against demonstrators, and arbitrarily detaining thousands of coup opponents.” Journalists, human rights defenders, and political activists continued to be victimized by threats and violence even after the restoration of democratic government. As a result, the U.S. government maintains restrictions on military aid to Honduras (Meyer, 2015:22-23). Dudley (2011b:902) asserts that “in addition to being over-politicized, they are ill equipped and ill-trained to handle such a challenge” as the security crisis afflicting Honduras today. The ICG (2014:24) concludes that Honduras' militarized policing measures “are often popular among crime-plagued populations seeking immediate relief, but they do not address the institutional vacuum that has allowed criminal organizations to thrive.”

One of the chief obstacles to institutional expansion and reform is the country's dismal tax base. Despite strong private sector opposition, the government did manage in June 2011 to pass a security tax to increase the revenues available to the security sector, but the tax rate remains a paltry 17.3 percent of GDP (Central Intelligence Agency,2015). Here the government faces a paradox: dissatisfied with the quality of public security provision, the country's elite increasingly rely on private security forces rather than raising their taxes, but without an increase in government revenues, public security continues to deteriorate (The Economist, 2011). Less-wealthy citizens have resorted to vigilante actions and social cleansing campaigns targeting suspected gang members (Berg & Carranza, 2015:11). Even more worrying, both Human Rights Watch and the U.S. DoS have reported paramilitary death squads targeting perceived delinquents, operating in collusion with state authorities (Rodgers, Muggah & Stevenson, 2009:13).

While the Honduran security and justice sectors are thus overwhelmed by the challenge of violent crime, significantly undermanned and under-resourced, and plagued by corruption and dysfunction, reforms are underway, including the September 2015 approval of an international Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH). The most promising development in recent years is perhaps the marked surge of civil society activism against corruption and impunity, signalling strong public demand for reform that should be supported and harnessed in international assistance programming.

Possible Policy Options

Potential Short-Term Policies

Support Reintegration Programs in Honduras

The Canadian government has an opportunity to work with Honduran authorities and civil society groups to develop and fund reintegration programs specifically geared towards criminal deportees. These programs could help track those deported from Canada once in Honduras. Colombia and Mexico are known to have successful deportee reintegration programs that could provide helpful lessons and experiences.Note 34 Deportees face a particularly high level of danger in the days and weeks after their return, when they are vulnerable, and may lack money and support networks in Honduras. This vulnerability is likely to be particularly acute for criminal deportees, who face stigma, and some of whom may face threats from criminal groups. Programs such as CAMR that provide immediate support to criminal and non-criminal returnees on arrival are limited by shortages in funding. Canadian government support for similar programs aimed at criminal deportees from Canada could help smooth deportees' return, and help to prevent crime and repeat migration.

CAMR (like a similar program in El Salvador, Bienvenido a Casa), provides a number of services for returnees, including: psychosocial support; professional, vocational and business-management training; substance abuse rehabilitation; and capacity building to allow host governments to take responsibility for the programs (McDonald, 2009). However, the human and economic resources allocated to these programs are insufficient, given the wide range of services they need to provide (e.g., housing, meals, employment training, drug abuse counselling and assistance in locating family) (McDonald, 2009). Further, these programs are not tailored to the unique needs and experiences of criminal returnees.

Expand Information-Sharing with Honduran Authorities

A lack of information sharing has been cited as an issue of U.S.-Honduras deportations. U.S. authorities do not provide a full criminal record for deportees, and do not report gang affiliation unless this is the primary reason for the deportation. Central American officials have asked the U.S. to provide more information on criminal deportees, including their gang affiliation (Seelke, 2014:7). There have been some efforts to redress this shortfall in information-sharing. In August 2015, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) signed a memorandum of cooperation with the Honduran police to enhance their ability to share information on criminal records of Hondurans repatriated from the U.S. (US ICE, 2014). Previously, in January 2014, the U.S. DoS and the DHS agreed to expand a program to share more information on criminal history with officials in Mexico and the Northern Triangle (Seelke, 2014:8). In a recent report, Michael Shifter called for the U.S. to “enhance information sharing on criminal deportees and support Central American reintegration programs for returned migrants,” via the Criminal History Information Program. “Given the increased levels of criminal deportations to Central America under the Obama Administration, such steps, although not a comprehensive reintegration strategy, would provide the critical information that national and local law enforcement need to understand the scope of criminality returning home and mitigate its risks” (Shifter, 2012: 22). The potential benefits of increased information sharing, however, must be balanced against the potential risks, particularly in light of the abysmal record of Honduran police in terms of human rights and corruption, and their participation in (or at least toleration of) violence against suspected gang members.

There are procedural and legal issues that make sharing this kind of information difficult. In Canada, CBSA officials are limited in the kinds of information they are able to share with foreign law enforcement authorities. In the case of criminal deportees, the CBSA shares publicly available information, such as a list of offences. However, it is limited by the Privacy Act in terms of what kind of information it can share with foreign authorities.Note 35 The CBSA does not, for instance, provide any details of the cases themselves, nor any information on sentencing, even in cases of serious organized crime.Note 36

Unlike with other countries, such as Jamaica, the Canadian government currently does not have a Memorandum of Understanding with the Honduran government pertaining to the deportation process. Consequently, any support provided by Canadian officials and any cooperation surrounding high-risk offenders is likely to occur on an ad hoc basis.Note 37 The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) may be better positioned to share information through its International Operations Branch and network of Liaison Officers, who are mandated to “maintain a link between law enforcement agencies in Canada and in their countries of accreditation in order to facilitate bilateral cooperation to advance criminal matters that have a Canadian connection” (RCMP, 2010).

Unlike the CBSA, the RCMP has the ability to decide to share information on a case-by-case basis.Note 38 The RCMP Liaison Officer stationed in Mexico City is well situated to participate in regional law enforcement information sharing, in particular with the Transnational Anti-Gang (TAG) initiative (the Centro Antipandillas Transnacional), which is made up of representatives of the U.S. FBI and regional law enforcement institutions (Immigration and Refugee Board, 2010). Canada is an external partner of the TAG through the Liaison Officer in Mexico City.Note 39 The RCMP often provides information to the CBSA through these connections with the TAG office; however, when there is no obvious reason to suspect gang involvement, the CBSA may never initiate any request for information to the RCMP.Note 40

Review Deportation to Honduras

Canada has a policy of not forcibly returning individuals to countries where their lives could be at risk due to conflict, insecurity or persecution. In cases where the risks are deemed to be too great, Canada can issue a Temporary Suspension of Removals (TSR). A TSR would not apply to those who have been convicted of a crime. TSRs have been issued in the past when conditions on the ground seriously jeopardized the safety of deportees due to political unrest (for instance, in Haiti in 2004), natural disasters (Haiti in 2010) or general insecurity. The difficult conditions facing Honduran deportees are well documented in this report. Poor economic conditions, social exclusion and lack of access to healthcare, shelter and medical assistance are not sufficient to justify a TSR. By contrast, forced gang recruitment, intimidation, abuse and murder could justify the implementation of a TSR. In light of the documented murder of at least 35 deportees from the U.S. upon their return to Honduras, it would be reasonable to conduct additional research into the conditions facing Canadian deportees returning to Honduras, paying particular attention to threats to their personal security.

Potential Medium- to Long-Term Policies

Continue to Support Security Sector Reforms

In September 2015, the Honduran government agreed to establish the MACCIH, which offers an entry point for more effective international assistance. The body is modelled after Guatemala's successful Commission against Impunity and Corruption in Guatemala (CICIG), but lacks the robust international investigative and prosecutorial powers that were crucial to CICIG's success. As it stands, MACCIH merely facilitates international advice to Honduran law enforcement institutions (see Casas-Zamora, 2015:11). Honduras should be encouraged to broaden MACCIH's mandate to maximize its potential to fight corruption and strengthen Honduran institutions.Note 41

Canada is already providing funding to strengthen law enforcement capacity, particularly against homicide, throughout the Northern Triangle (Justice Education Society, 2015), but much more support is needed. Canada has an opportunity to further contribute to peace and security in Honduras by supporting security sector reform programs, targeting in particular the country's failing police force. A cornerstone of this assistance should be to discourage the continued use of the discredited mano dura policies that have only exacerbated the adverse security situation. Reforms should instead emphasize community-based policing programs, based on a service provision model attentive to citizens' day-to-day needs, particularly for the most marginalized and violence-stricken areas of the country in order to reduce the threats posed by gangs and criminal recidivism.Note 42 Indeed, successful community policing was a key factor in preventing the spread of the maras and their associated violence in Nicaragua (Santamaría, 2013:86).

To date, the majority of international assistance has focused on building military capacity while overlooking the police and judicial institutions as arguably more important parts of any long-term solution. The U.S. Central American Regional Security Initiative, for example, focuses on increasing security capacity rather than mounting institutional reform. The focus should be on local-level (rather than solely national) institutions as the ones most vulnerable to criminal capture. A recent World Bank Report (Berg & Carranza, 2015) reviews current community-based prevention programs in Honduras, while the Colombian cities of Bogotá and Medellín have over the last decade mounted successful violent crime reduction strategies from which lessons can be drawn (see Felbab-Brown, 2011).

The Central American region has received nearly USD 2 billion of international security assistance over the last 10 years.Note 43 Poor coordination has limited the effectiveness of this assistance, making it vital that any security sector assistance be undertaken in close coordination with international donors, regional initiatives and individual countries in the region.Note 44

Conclusions

The impact of deportation from Canada on organized crime in Canada and Honduras should not be overstated. Owing to the relatively small population of Hondurans currently living in Canada and the small numbers deported annually (particularly in relation to the much larger numbers deported from the U.S. and Mexico), there is little evidence to date that the flow of deportees has had substantial impacts on either country. There is evidence, however, that Honduran gangs have begun to operate in a number of Canadian cities. While these groups undoubtedly tap into transnational drug trafficking networks, they do not have direct connections to mara cliques in Honduras.

There is little evidence—either in the literature or in interviews conducted with law enforcement officials and policy researchers in Canada, the U.S. and Honduras—of a direct connection between organized crime groups in Honduras and in Canada. Rather, Honduran organized crime groups are part of a chain of criminal organizations that are responsible for the transportation of the majority of cocaine from South America producers to North American markets, including Canada. Most of the transnational flow of drugs moves through the U.S., where other intermediaries handle it before it enters Canada. Moreover, research literature and CBSA statistics indicate that return migration to Canada on the part of previously deported migrants is far less common than in the U.S. As a result, the direct threat to Canadian public safety posed by offenders who have been deported to Honduras is likely to be minimal.

Deportees to Honduras return to a country that is facing urgent humanitarian challenges. They frequently find themselves unable to secure suitable housing, healthcare and employment, owing to the extremely difficult economic conditions in Honduras, as well as social stigma, and, for some, the threat of violence. There are a number of Honduran organizations providing social services to deportees, but they remain under-resourced and unable to cope with the massive flow of return migrants, particularly from the U.S. Canada can play an important role in international efforts to support deportees and the Honduran authorities, while pushing for broader security and justice reform in Honduras.

Acronyms

Canada

- CBSA

- Canada Border Services Agency

- CISC

- Criminal Intelligence Service of Canada

- IRPA

- Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (2001)

- RCMP

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- TFWP

- Temporary Foreign Worker Program

Honduras

- CAMR

- Centro de Atención al Migrante Retornado

- CIGIG

- Commission against Impunity and Corruption in Guatemala

- CPSR

- Commission on Public Security Reform

- MACCIH

- Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras

United States

- DHS

- Department of Homeland Security

- DoS

- Department of State

- FBI

- Federal Bureau of Investigation

- ICE

- Immigration and Customs Enforcement

- USAID

- United States Agency for International Development

General

- DTOs

- Drug Trafficking Organizations

- GDP

- Gross Domestic Product

- ICG

- International Crisis Group

- IOM

- International Organization for Migration

- ISSAT

- International Security Sector Advisory Team

- NGOs