Joining The Circle - Identifying Key Ingredients for Effective Police Collaboration within Indigenous Communities

Disclaimer

Public Safety Canada funded this project as part of the interim response to the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. The views and findings reflect those of the author(s) and those who kindly agreed to participate in the project.

Prepared by:

Dr. Chad Nilson

Barb Mantello

November 2019

About the Paper

This paper serves as the final deliverable resulting from a contribution agreement between Public Safety Canada and Community Safety Knowledge Alliance (CSKA). Its purpose is to inform the development of tools, programs, and future policies concerning police relationships in Indigenous communities.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the staff, Elders, and community members of Muskoday First Nation, English River First Nation, and Prince Albert Métis Women’s Association for their guidance and support in the planning and delivery of this project.

About Community Safety Knowledge Alliance

CSKA is a non-profit organization that supports governments and the broader community safety and well-being sector in their drive toward new and effective models for, and approaches to, community safety and well-being. Through its four lines of business (research, evaluation, technical guidance/support and professional development) CSKA mobilizes, facilitates and integrates research and the development of a knowledge base to inform how community safety-related work is organized and delivered.

For further information on Community Safety Knowledge Alliance, please contact:

Shannon Fraser-Hanson, Manager

Community Safety Knowledge Alliance

120 Sonnenschein Way

Saskatoon, SK S7N 3R2

(306) 384-2751

sfraserhansen@cskacanada.ca

www.cskacanada.ca

Project Director: Cal Corley

Chief Executive Officer

Community Safety Knowledge Alliance

(613) 297-6728

ccorley@cskacanada.ca

Paper Authors:

Dr. Chad Nilson

(306) 953-8384

LSCSI@hotmail.com

Barb Mantello

(403) 360-2754

bmantello@outlook.com

To reference this work, please use the following citation:

Nilson, C. and Mantello, B. (2019). Joining the Circle: Identifying Key Ingredients for Effective Police Collaboration within Indigenous Communities. Saskatoon, SK: Community Safety Knowledge Alliance.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Chad Nilson has a wide background in researching, developing and measuring collaborative social innovations for non-profit, municipal, provincial, federal and Indigenous organizations. As a community-engaged researcher, advisor and evaluator, Chad has contributed broadly to the field of community safety and well-being. Chad’s reputation and expertise has drawn him into many national and international projects of high profile and impact. He is primary investigator for the Living Skies Centre for Social Inquiry and a community-engaged scholar at the University of Saskatchewan’s Centre for Forensic Behavioural Science and Justice Studies. In these roles he has been invited to lead and mentor the measurement and development of community safety and well-being initiatives in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Nunavut and Prince Edward Island. Chad’s relationship and involvement with Indigenous communities spans multiple nations and tribal territories.

Barb Mantello Barb has a practical and instructional background in criminal justice. She spent 10 years working with young offenders before embarking on a post-secondary teaching and research career. Prior to retiring as Chair of the School of Justice Studies at Lethbridge College, Barb spent most of her academic years teaching and supporting students in pursuit of corrections, policing and other public safety careers. Barb has extensive experience with the development and implementation of applied learning at the college and university level. Part of that experience includes developing courses for face-to-face and online teaching platforms; completing curriculum reviews; and designing a specialized, competency-based cadet training program aimed to assist police agencies in hiring selections for their service. Based in Lethbridge, Alberta, Barb now provides research, advising, and developmental support to community safety organizations in Canada.

1.0 INTRODUCTION

Opportunities for improving the safety and well-being of communities in Canada partially lie within the relationships that police have with citizens, leaders, and other human service providers (Lang et al., 2009; Rajaee et al., 2013; Skogan, 2006). This is especially true in First Nation, Métis, and Inuit (hereafter referred to as Indigenous) communities, where the importance of strong police-community relations is undeniable (Cunneen, 2007; Griffiths & Clark, 2017; Linden, 2005).

One of the major challenges impacting safety and well-being in Indigenous communities is violence against women and girls (Brennan, 2009; Kwan, 2015). While violence on its own is a serious harm, the occurrence of violence further impacts victim employment (Reeves & O’Leary-Kelly, 2007), feelings of safety (Johnson & Dawson, 2011), physical health (Vos et al., 2006) and life satisfaction (Statistics Canada, 2009), among other hardships. At the community level, violence impacts stability in housing (Kirkby & Mettler, 2016), education (Lloyd, 2018), mental wellness (Statistics Canada, 2009), service access (AuCoin & Beauchamp, 2007) and economic outcomes (Zhang et al., 2013), among other community safety and well-being indicators.

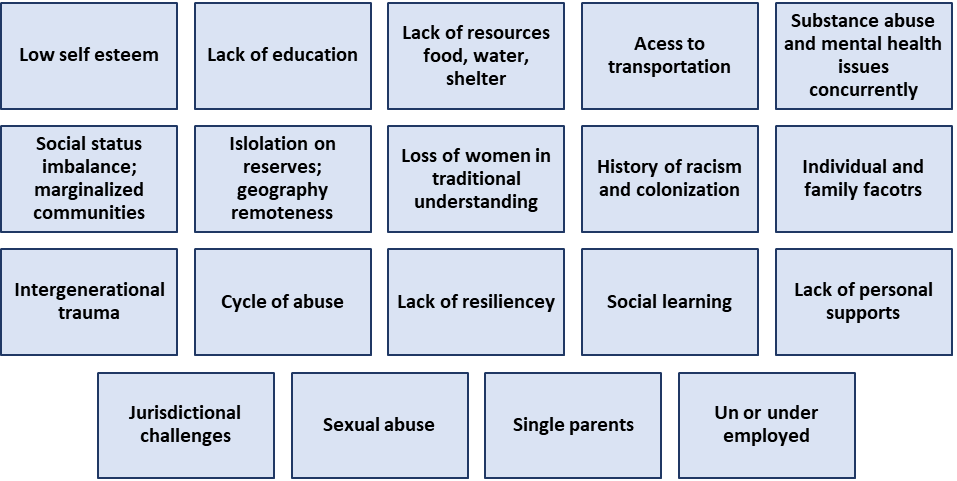

Scholars of violence (Brownridge, 2008) find Indigenous women are, on average, four times more likely to experience violence than non-Indigenous women. Much of this is linked to the disproportionate accumulation of risk factors for violence that Indigenous women experience (Burnette & Renner, 2017; Pearce et al., 2015). Another contributor to this disproportion is that Indigenous women face multiple barriers in accessing help and support in both violence intervention and prevention (Davis & Taylor, 2002; Kurtz et al., 2013).

Police in Canada have an opportunity to work collaboratively with Indigenous communities to move upstream and address both the root causes of violence, as well as identify and resolve barriers to prevention/intervention services and support that Indigenous women face (Chrismas, 2016; Griffiths, 2019). While this pathway is not always clear or easy, there are opportunities for police to improve their policies, practices, and processes when engaging Indigenous communities. According to some experts (Chrismas, 2012), improved communication, community engagement, and empowerment can better align police agencies with the values of Indigenous people. This in turn, can have a positive impact on both police-community relations and community safety and well-being outcomes.

The purpose of this paper is to identify the key ingredients, techniques, challenges, and opportunities for police professionals to engage in effective collaboration within Indigenous communities. The consultations and data gathered for this paper identify how police involvement in information-sharing and collaboration with various Indigenous human service sectors can help reduce barriers, establish trust for police, and reduce violence against women and girls.

Key components of different multi-sector collaborative models were explored in preparation for writing this paper. Using a lens of opportunities and key ingredients, the analysis of data captured through this project identified leading police practices, skills and commitments that can be enhanced through tools, programs, and future policies for provincial, Indigenous and federal government. The intent of this paper is to not only inform the future but strengthen and validate existing efforts to improve police-Indigenous relations. The opportunities identified in this project show great potential for helping police professionals become successful in joining the circle and become an important part of Indigenous communities in Canada.

The next section of this report begins with a background on the project, including a presentation of key objectives and outcomes, major research questions, and an explanation for how the entire project was guided by Indigenous communities. Following the background section is an overview of three key literature areas. They include: violence against Indigenous women, barriers that Indigenous women face, and collaborative opportunities for police to help reduce the risks and barriers associated with violence against Indigenous women and girls. Next, the methodology of this study involves a comparative model analysis, researcher observations, and interviews with key respondent groups: community stakeholders, topic experts, and collaborative model participants. Findings of this research are organized by the original research questions posed. Finally, the key deliverable in this paper is a list of actionable recommendations that police administrators, government leaders, and frontline professionals can implement in order to effectively collaborate with Indigenous communities in a way that reduces violence against women and girls.

2.0 BACKGROUND

The impetus of this project can be traced back to Public Safety Canada’s response to the interim recommendations of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (2019). Under its Policy Development Contribution Program, Public Safety Canada announced funding opportunities to support research that contributes to cooperation between police services, social service providers and Indigenous peoples. The intent was for funded research to “inform the development of tools and resources which, once complete, will be made available to police services throughout Canada to enable the delivery of culturally competent police services to Indigenous peoples” (Public Safety Canada, 2019: 1).

As a major contributor to linkages between research, practice and policy in Canada, Community Safety Knowledge Alliance (CSKA) submitted a proposal for funding in March of 2019. By May of 2019, CSKA signed a contribution agreement with Public Safety Canada to undertake this project. This paper serves as the final deliverable outlined in the agreement. Work for this project commenced in May and was completed in November of 2019.

2.1 Objectives & Outcomes

This project was driven by several objectives originally outlined in the proposal, and reinforced during preliminary and interim reporting activities to Public Safety Canada. They include:

- Identify areas of police policy and practice requiring improvement;

- Identify successful models of multi-sector collaboration that reduce violence against Indigenous peoples;

- Determine key ingredients, traits and skill-sets that contribute to positive police-Indigenous relations;

- Prepare recommendations that support the development of tools and resources for police (and other human service professionals) to use in improving collaborative opportunities to reduce violence against Indigenous people.

The objectives for this project were designed to help produce three intended outcomes. These include:

- Enhanced awareness of key challenges in police-Indigenous relations, together with the identification of key mitigating strategies and tactics;

- Improved understanding of, and commitment to, adopting multi-sector collaboration within an Indigenous context;

- Knowledge of opportunities to reduce violence against Indigenous people through effective multi-sector collaboration.

2.2 Work Plan

To begin working on these objectives, the authors designed a project work plan that spanned the duration of the project. Various components of the work plan were dependent upon completion of other components in the plan. To outline each of these activities, Table 1 lists each activity, provides a description of the activity, and a timeline.

PROJECT ACTIVITY |

DESCRIPTION |

DATE (2019) |

|---|---|---|

Mobilize Partners |

Engaged Indigenous partners and multi-sector collaboration stakeholders in project planning and design. |

May |

Establish Project Questions |

Utilized feedback and guidance from Indigenous partners to create research questions. |

May |

Determine Approach |

Finalized goals of project and developed strategy for pursuing the research questions. |

Jun |

Initial Reporting |

Submitted preliminary outline of project and initial cashflow. |

Jun |

Conduct Literature Review |

Examined variety of literature types and sources to determine case examples and common practices. |

Jun – Jul |

Develop Consultative Methodology |

Prepared process for data collection and analysis. |

Jun |

Conduct Initial Outreach |

Reached out to stakeholders for coordination of dialogue, refinement of approach, and suggestions of respondents. |

Jul |

Finalize Data Tools |

Prepared tools for data collection during consultative process. |

Jul |

Conduct Consultations |

Gathered observations, feedback, suggestions from Indigenous communities, subject matter experts, and key stakeholders. |

Jul – Nov |

Secondary Reporting |

Submitted interim activity report, cashflow and financial statement. |

Aug |

Model Analysis |

Assessed collaborative human service models on criteria determined through consultation process. |

Sep – Oct |

Collaboration Observations |

Made observations of collaborative models and practices involving police partners. |

Sep – Nov |

Organize Data |

Separate and organize data as it arrives. |

Jul – Nov |

Analyse Data |

Analyze data gathered during research project. |

Nov |

Prepare Report |

Prepare evidence and outline recommendations for improving police-Indigenous relations. |

Nov |

Final Reporting |

Submit final cashflow statement, final financial statement, final activity report, and final report to Public Safety Canada. |

Nov |

2.3 Indigenous Guidance

To deliver an appropriate and effective resource for police in Canada, the research team included Indigenous guidance starting at the proposal stage and continuing through to the end of the project—where recommendations were made. To secure this guidance, the authors approached three separate guidance cohorts of Indigenous human service delivery. The first were Elders, staff and community members of Muskoday First Nation—a Cree and mixed tribe community in plains country. This cohort has multiple experiences developing collaborative human service models with police. The second guidance cohort were Elders, community members, and staff of English River First Nation—a Dënesųłiné community in the Northern forests. This cohort also has experience collaborating with police on multiple projects in their community. The third guidance cohort included Elders, staff, and community members belonging to Prince Albert Métis Women’s Association. This organization works to reduce violence against Indigenous women and girls, while also improving the resilience of Indigenous families to various forms of vulnerability (e.g., HIV, unemployment, criminality, overdose, homelessness, poverty).

Members of the guidance cohorts were approached for feedback and guidance at the proposal, planning, data collection, and results preparation stages of this project. Interaction with the guidance cohorts occurred through face-to-face visits, conference calls, and videoconferencing. Members of the guidance cohorts not only helped shape the methods and approach, but also provided insight into some of the themes, challenges, and trends appearing in the research. Another benefit of the guidance cohorts was their assistance in identifying and accessing interview respondents. Feedback from members of the guidance cohorts indicated that their participation in this project was “meaningful and motivating”. Several of the guidance cohort members provided additional insight during the data collection stage (i.e., interviews).

2.4 Research Questions

Several key questions guided this research project. These questions were developed following consultations with the project’s Indigenous guidance cohorts, reflection on the original project proposal, and examination of the key literature areas that were most relevant to the project. To assist in organizing efforts required by the project, the research questions are organized into four key themes (see Table 2).

THEME |

QUESTIONS |

|---|---|

Defining the Problem |

1. What conditions or barriers contribute to increased vulnerability of women and girls to violence in Indigenous communities? |

2. What police-related challenges impact efforts to reduce vulnerability and barriers to support for women and girls in Indigenous communities? |

|

Identifying Solutions |

3. What opportunities are there for police to contribute to a reduction in vulnerability and barriers to support? |

Building |

4. What past community experiences can we learn from to inform future directions for police-Indigenous community relations? |

5. Moving forward, what are the key ingredients for effective collaboration among police, human service providers and Indigenous peoples? |

|

Recommendations |

6. What key features and characteristics of future police tools and resources would best contribute to a reduction in vulnerability to violence among Indigenous women and girls? |

3.0 LITERATURE REVIEW

To begin answering the research questions, several different bodies of literature were examined for insight and direction. The first of these is the literature exploring violence that impacts Indigenous women and girls. The review highlights some risk factors connected to violence, as well as the barriers impacting women at-risk for or already exposed to violence. Within the discussion on barriers facing Indigenous women is a sub-section on police-related challenges. A description of the different contributing factors to violence, along with barriers to support, show the need for police involvement in multi-sector collaboration. Exploring this further, the literature review then examines key concepts, practices, and approaches to multi-sector collaboration in human service delivery. This is followed by a review of collaborative models and key ingredients for collaboration mentioned in the literature.

3.1 Violence Impacting Indigenous Women and Girls

Violence against Indigenous women and girls in Canada is a significant national concern (Government of Canada, 2014). In 2009, a Statistics Canada survey found that Indigenous women were almost three times more likely to be violently victimized than non-Indigenous women. The majority of these women were between 15 and 34 years of age, and reported experiencing multiple episodes of violence (Statistics Canada, 2012).

According to the RCMP (2014), despite the fact that Indigenous women make up four percent of Canada’s population, they represent 16 percent of all murdered women in Canada, and 12 percent of all missing women on record. This disproportion can be explained in part by an elevated risk of partner violence for Indigenous women compared to non-Indigenous women in Canada (Brownridge, 2008; Daud, et al., 2013; Kirkup, 2016; Pederson, Malcoe & Pulkingham, 2013).

An examination of the literature on risk factors for violence against Indigenous women revealed a wide range of determinants. Some of the personal risks include alcohol use (Clough et al., 2014), drug use (Pearce et al., 2015), low emotional control (Jewell & Wormith, 2010), poor communication skills (Burnette & Hefflinger, 2017), poor physical health (Bianchi et al., 2014), and cognitive limitations (Keeling & van Wormer, 2011). Some of the risks considered to be more situational in nature, include historical oppression (Burnette & Hefflinger, 2017), parent alcohol abuse (Burnette, 2016), economic insecurity (Daoud et al., 2013), geographic isolation (Varcoe & Dick, 2013), low income (Burnette & Renner, 2017), and past exposure to violence (Abraham & Tastsoglou, 2016). Additional risks include infidelity, family conflict, and poor mental health (Collins et al, 2002).

3.2 Barriers to Services and Support

One of the main concerns of this research is the barriers Indigenous women face when reaching out for support because they are at-risk for or have been exposed to violence. According to some researchers (Davis & Taylor, 2002), Indigenous women are often “invisible”, which makes recognizing barriers impacting Indigenous women even more challengingFootnote1 . Others (Kurtz et al., 2013) argue that many Indigenous women do not access services because they feel their voices are silenced. Much of this is rooted in the deep effects of colonialism, which undermine both efforts to prevent violence, as well as efforts to support women impacted by violence (Kwan, 2015).

According to service providers working to reduce violence against women (Muskoday Community Health Centre, 2012), the consequence of this history is a deeply embedded social devaluing of Aboriginal women in Canada. In pre-colonial times, despite having different roles within society, Aboriginal men and women were generally regarded as equals. With European settlers also came the introduction of patriarchal and hierarchical systems of power. This is evident through the administration of Western policies such as The Indian Act. According to some observers (National Aboriginal Circle Against Family Violence, 2006) “The Indian Act was particularly harsh on Native women. It imposed male-lineage and wrote male-female inequality into law” (p.12). The Indian Act formally justified the subordination of women in Aboriginal societies. Most reserve communities in Canada are still under the authority of the Indian Act, though some communities have taken steps to reduce the power differential and increase equality between men and women at the organizational/institutional level. However, there is still much more work that needs to be done as patriarchy and male domination is powerful and persistent across Canada and women’s struggle for equality is continually undermined (Pederson, Malcoe & Pulkingham, 2013).

The impact of gender differences has created a lot of additional barriers for women. These barriers come in four different types. These include personal, situational, systemic, and community-based (Ooshtaa, 2019). The following subsections further explain each barrier type.

Personal Barriers

Personal barriers include barriers that stem from an individual’s skills, abilities, personality, capacity, and behaviour. Some of the more common personal barriers impacting women who are at-risk for or who have been exposed to violence include distrust of service providers (Setting the Stage, 2013), lack of confidence in the police or justice system (Cao, 2014), low self esteem (University of Michigan, 2009), poor communication skills (Hegarty & Taft, 2001), anxiety accessing support from others (Narasimha et al., 2018), lack of awareness of services in the community (Du Mont et al., 2017), reluctance of victims to ask for help (Davis & Taylor, 2002), and cognitive limitations (Keeling & van Wormer, 2011).

Situational Barriers

Situational barriers include circumstances about or related to the individual which affect their ability to engage in services. Unlike ‘personal barriers’, they do not pertain to the individual, but rather about things going on around them (Ooshtaa, 2019). Some examples include lack of childcare (Burman, Smailes & Chantler, 2004), transportation (Setting the Stage, 2013), geographic isolation (Griffiths, 2019), financial ability (Burman & Chantler, 2005), and lack of family support (Canadian Resource Centre for Victims of Crime, 2011).

Systemic Barriers

Systemic barriers involve certain obstacles and challenges that are attributable to some sort of design feature, structure, rule, capacity, policy, or other element of the human service system (Dylan, Regehr & Alaggia, 2008). Common examples include wait-times (Ooshtaa, 2019), long and intrusive intake procedures (Setting the Stage, 2013), demanding admission requirements and steep entrance thresholds (Nilson & Okanik, 2016), limited service hours (Setting the Stage, 2013), a lack of resources (Daoud et al., 2013), un-coordination of existing resources (Aboriginal Affairs & Northern Development Canada, 2012), a lack of privacy and anonymity in small communities (Nilson & Okanik, 2016), ineffective services (Iyengar & Sabik, 2009), and barriers for victims when trying to find support.

One of the more challenging systemic barriers for women is conflicting approaches between support delivery models in the violence, mental health, and addiction sectors. According to Haskell (2010), while violence against women services are often based in feminist frameworks that advocate empowerment and social justice, health services such as addiction support often emphasize individual accountability. According to the Canadian Women’s Foundation (2011), priorities between the three sectors may also differ, with support for violence focusing on safety, addictions services focused on sobriety, and mental health services on stabilization. Without recognition of the connections between violence, mental health, and substance use—services and supports are unlikely to meet the needs of survivors.

Another major systemic barrier for women exposed to violence is that many support services (e.g., shelters, therapy, respite) are limited to those women who are clean and sober. Research shows a multi-directional relationship between violence, mental health issues, and substance abuse (Canadian Women’s Foundation, 2011; Haskell, 2010; Rossiter, 2011). As such, blanket restrictions for women seeking support based solely on mental wellness and/or substance use are essentially denying women support due to their symptoms of violence and/or attempts to cope with their environment (Setting the Stage, 2013). In turn, women exposed to violence may feel that they are being negatively judged for responding to violence in the way they choose. For some women, this judgement may be experienced as yet another form of disempowerment (BC Society of Transition Houses, 2011).

A final systemic barrier is turnover among service provider staff. Helpers are at risk of experiencing compassion fatigue, burnout, and vicarious/secondary trauma (Ferencik & Ramirez-Hammond, 2011; McEvoy & Ziegler, 2006). Vicarious trauma is strongly associated with higher rates of illness, sick leave, and staff turnover. Vicarious trauma may also contribute to lower morale in the workplace and lower productivity (Ferencik & Ramirez-Hammond, 2011). All of these pressures impact the quality and availability of care for women at-risk for or exposed to violence.

Social Barriers

When it comes to social barriers, perhaps the two most impactful barriers are stigma and shame. As Haskell (2010) argues, disclosing victimization of violence may bring shame, not only to the woman, but to her family as well, which prevents many women from seeking support. Many victims would prefer to heal in private, behind dark glasses and closed curtains. According to some experts (Canadian Resource Centre for Victims of Crime, 2011), their physical pain is more bearable than the shame and humiliation they are experiencing.

A third major social barrier to accessing support is fear. It is common for women and girls who have been abused to live in a high level of justifiable fear due to ongoing violence. Female victims of violence may fear leaving their partner due to increased chances that the violence will continue or even escalate (Hotten, 2001). Women may fear that no one will believe them and/or they will be judged by family and friends (Narasimha et al, 2018). They may have a fear of losing control through engagement with the justice system and, therefore, be reluctant to work with the police and the courts. Mothers may fear being seen as a ‘bad mother’ if their children witnessed the abuse. They may also fear the possibility of having their children apprehended by child protection services if they access support. Finally, women may fear potential changes in lifestyle if they no longer remain in their relationship (Setting the Stage, 2013).

Two additional common social barriers to accessing supports include denial and normalization of violence. From a community perspective, there is still a great tendency for people to ignore what happens behind closed doors. While theft, child abuse, or even animal cruelty might quickly be reported to appropriate officials, violence against women may not always be reported (Canadian Resource Centre for Victims of Crime, 2011). From a victim perspective, normalization occurs through a process of rationalizing the violence, and blaming stress, substances, or financial difficulties for acts of violence towards them. On top of all this internal normalization, a perpetrator may make promises that the violence will never happen again. As part of the ‘cycle of violence’, many women and girls want to believe this to be true (Canadian Resource Centre for Victims of Crime, 2011).

Community Barriers

When it comes to addressing problems of violence on-reserve, there are several challenges which make the process more difficult than addressing violence off-reserve. These challenges stem largely from most on-reserve communities having small populations (Government of Canada, 2004), geographic isolation (Griffiths, 2019), long histories of violence (Griffiths & Clark, 2017), a lack of resources (Bopp, Bopp & Lane, 2003), considerable social and economic problems (Assembly of First Nations, 2007), and drug and alcohol use (Gelles & Cavanaugh, 2005). Attempts to reduce these barriers are challenging, largely because they extend beyond the reach of most violence intervention and prevention programs. According to some observers (Guggisberg, 2019), the best approach to reduce community barriers are through culturally-appropriate methods designed with and supported by local community stakeholders.

3.2.1 Police-Related Barriers

At the centre of this research project is the question of how police-related circumstances may serve as barriers to services and support for Indigenous women at-risk or exposed to violence. A review of the literature identified four types of police-related barriers. Considering the small size of most Indigenous communities, each of these barriers can be widely felt, and in-turn, can have long-term implications for the members of these communities (Jones et al., 2014).

Police Perception

The first barrier identified in the literature concerned police perceptions of Indigenous communities and of Indigenous women. According to research on this topic (Lithopoulos & Ruddell, 2011), the perception that police have of individuals impacts their approach to each situation. In the case of victims to violence, for example, police support for victims is often contingent on the severity of injury (Campbell, 1998), credibility (Frohman, 1991), sexual history (Campbell, 2006), and substance use (Campbell 2006). Another determinant of police support for victims is the officer’s own stereotypes of Indigenous people (Neugebauer, 2000). According to Palmater (2016), racism and sexism among policing professionals is a reality in Canada. These stereotypes have major implications for violence against Indigenous women—including the way in which victims of violence approach the judicial process (Dylan, Regehr & Alaggia, 2008).

A contributor to these stereotypes is the actual policing environment within which officers stationed in Indigenous communities must work in. Results of the Ipperwash Inquiry indicate that the reasons that community policing models are challenged in Indigenous communities is because of “the placement of officers from outside the community, people with little knowledge, little sensitivity and even less interest in knowing the residents, the lack of trust between police and members of the community, and, the high crime rates that force police with limited resources to focus on responding to problems, with virtually no time for prevention” (Human Sector Resources, 2004: 9).

Public Perception

The second type of police-related barrier impacting services and support for Indigenous women at-risk of or exposed to violence is public perception. According to Cao (2014), Indigenous people have lower level of trust and confidence in police. This sense of distrust can lead to a lack of cooperation with police investigations and the perception and experience that police officers are indifferent to the plight of victims. This is particularly problematic in cases involving domestic violence and sexual assault (McGillivray & Comaskey, 1999).

Another factor in public perception of police is the outcomes of police work in Indigenous communities. According to Rhoad (2013), police failures to protect Indigenous women and girls from violence and violent behavior add to longstanding tensions between police and Indigenous communities. The lack of success in protecting victims of violence further undermines police efforts to build positive relationships with community members.

Policing Structure

The third type of police-related barrier concerns the structure and design of policing services in Canada. Most Indigenous communities are policed by a provincial policing service (e.g., Ontario Provincial Police, Sureté du Québec) or the RCMP in all other provinces and territoriesFootnote2 . By being organized on a provincial or national scale, police officers are often transferred between different detachments every few years. This mobility challenges the ability of police officers to develop lasting relationships that are important for effective violence prevention/intervention (Lithopoulos, 2015).

Another structural issue is the size of detachment areas within which Indigenous communities are located. Since most Indigenous communities have small populations, not only are a small number of officers assigned to each community, but those officers are also assigned to also police other communities in the area. Due to the high visibility of police activity in these communities, everyone sees and knows what the police are doing. This high visibility brings significant consequence to small detachments who are quite often only seen under negative circumstances (e.g., arrest, fight breakup) (Griffiths, 2016).

Reporting Violence

Another police-related challenge involves the reporting of violence to police. Generally, many occurrences of violence are never actually reported to police (Status of Women Canada, 2019). Those incidents which are reported, most often involve serious violence, an intoxicated offender, or child witnesses. These more complicated situations, while certainly important to address, usually involve some degree of mandated services. When services are mandated, there tends to be less opportunity for multiple human service providers to collaborate with one another in helping the victim and perpetrator (Nilson, 2014).

Another challenge with violence being reported to the police is that it is often very limited to a smaller cohort of victims. An Australian study (Voce & Boxall, 2018) of violence reporting showed that victims who are female, non-white, experiencing frequent violence and who have been abused in the past, are more likely to report. Unfortunately, Indigenous women who are just newly at-risk or who have limited exposure to violence, tend to report less. This marks a lost opportunity to support women and girls upstream prior to violence becoming a regular occurrence in their life (Before it Happens, 2019).

A third challenge with reporting of violence is that it can negatively impact public opinion of the police. According to Griffiths and Clark (2017), under-reporting of violence to the police undermines police ability to prevent or intervene in escalations of risk to violence. When this occurs, it not only impacts collaboration with the community, but it suggests that police are indifferent to the plight of victims. Fueling this under-reporting further, is a distrust for the police that is often tied to police inability to successfully reduce violence in communities (McGillivray & Comaskey, 1999).

3.3 MULTI-SECTOR COLLABORATIVE SOLUTIONS

As the above literature review identified, geographic isolation, social conditions, a history of distrust of the police, combined with the structure through which police services are delivered in Canada, can present significant challenges to the safety and well-being of Indigenous communities. However, the unique characteristics of Indigenous communities provide police with opportunities in multi-sector collaboration that can help communities overcome many of these barriers (Griffiths, 2019). Supporting this claim, Chrismas (2016) proposes that the pathway to enhancing positive relations between police and Indigenous communities is through increased multi-sectoral collaboration around social problems.

Collaboration scholars (Agranoff & McGuire, 2003) argue that multi-sector collaboration is an effective approach for addressing a variety of social problems. In fact, much of what we know about risk factors for violence concern the risk factors of these other social problems (Barton, Watkins & Jarjoura, 1997). In fact, other researchers (Echenberg & Jensen, 2009; Newcomb & Felix-Ortiz, 1992; Shader, 2003) suggest that various risk factors for individual harms are not only related to one another but combine to have a cumulative effect. The composite nature of risk for those individuals and families most affected by social problems has prompted several observers (Amuyunzu-Nyamongo, 2010; Hammond, et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2009; Pronk, Peek & Goldstein, 2004) to advocate for multi-disciplinary approaches to addressing the needs of individuals presenting with composite risk.

Additional research shows multi-sector collaborative approaches to improve social outcomes in the areas of sexual exploitation (Clayton et al., 2013), sexual health (Landers et al., 2011), community school support (Anderson-Butcher et al., 2010), youth development (Barton, Watkins & Jarjoura, 1997; Hernandez-Cordero et al., 2011), population aging (Hee Chee, 2006), child protection (Darlington & Feeney, 2008), health promotion (de Vries et al., 2008), home care (Dodd et al., 2010), special needs education (Farmakopolous, 2002), community-based mental health (Fieldhouse, 2012), housing (George et al., 2008), disease epidemics (Thomson et al., 2016), addictions (Treno & Holder, 2002), primary health (Lewis, 2005), employment support (Lindsay, McQuaid & Dutton, 2008), and of course, violence (Banks et al., 2009).

Collaboration among human service professionals is described as “an interpersonal process through which members of different disciplines contribute to a common product or goal” (Berg-Weger & Schneider, 1998: 98). Some (Claiborne and Lawson, 2005) add that collaboration is a form of collective action that involves multiple agencies working together to address mutually-dependent needs and complex problems. Others (Bronstein, 2003: 299) explain that collaboration is a partnership process that involves “interdependence, newly-created professional activities, flexibility, collective ownership of goals and reflection on process”.

Success of collaborative relationships requires much more than simply mutual interest of the partners. Some of the key determinants of successful collaboration include past experience with collaboration (Daley, 2009), the design and function of the collaborative process (Bolland & Wilson, 1995), knowledge among the partners (Boughzala & Briggs, 2012), communication patterns (Broom & Avanzino, 2010), marketing of the collaborative (Austin, 2008), organizational characteristics of the partners (Lehman et al., 2009), trust between partners (Weaver, 2017) and both non-spatial and geographic proximity of partners to one another (Knoben & Oerlemans, 2006).

Once collaboration begins to occur, the partners begin to experience a number of benefits. According to Kaye & Crittenden (2005), collaboration legitimates an issue, attracts broader support, and creates new synergies. Another benefit of collaboration is that it helps to close service gaps and increases the capacity of the partners involved (Nowell & Foster-Fishman, 2011). Perhaps the most common benefits of multi-sector collaboration include the broadened understanding of an issue (Sanford et al., 2007) and the diversified knowledge and skills to address the issue more effectively (Hulme & Toye, 2005).

While there are several documented benefits of multi-sector collaboration, challenges also exist. Some of the more common challenges mentioned in the literature on multi-sector collaboration include differences in prioritization between the partners (Margolis & Runyan, 1998); barriers to information sharing (Munetz & Teller, 2004); power and autonomy to fulfill obligations (Byles, 1985); difficulties with shared measurement (Davis, 2014); and the general costs of collaboration itself (e.g. time, funding) (Kaye & Crittenden, 2005).

To overcome these challenges, there is value in being mindful of key ingredients suggested for multi-sector collaboration models. Following a study of 126 collaboratives involving criminal justice professionals in Canada, Nilson (2018) identified and categorized several ingredients into five main themes. These include: partnership, process, commitment, resources and perspective. Table 3 lists these ingredients under each theme.

THEME |

KEY INGREDIENTS |

|---|---|

Partnership |

|

Process |

|

Commitment |

|

Resources |

|

Perspective |

|

(Source: Nilson, 2018: 24)

3.3.1 Police Involvement in Collaboration

Over the past two decades, police involvement in multi-sector collaboration has increased in Canada and other democracies. Some of this is driven by the belief that collaborative models foster the type of inclusiveness, support, and shared ownership that best support vulnerable populations—thereby better improving community safety (Gilling, 1994). Others (Heller, 1992) point out that multi-sector collaboration promotes greater efficiency in service delivery and expands agency leverage through partnerships and resource-sharing. In more recent years, perhaps the most prevalent reason for police to become involved in multi-sector collaboration is because of the opportunity it provides to simply “do better” (Mcfee & Taylor, 2014).

The literature on multi-sector collaboration shows police involvement in a wide variety of models. Some of these include service-based collaboratives (Bruns, 2015; Cherner et al., 2014; Mears, Yaffe & Harris, 2009; TRiP, 2016); addictions and housing initiatives (Tsemberis, 2011); police and mental health crisis teams (Belleville Police Service, 2007; Chandrasekera & Pajooman, 2011); health and education partnerships (Buchanan, 2008); complex case management (Clark, Guenther & Mitchell, 2016; Fraser Health, 2017; Gaetz, 2014); police and domestic violence teams (Corcoran & Allen, 2005; Nilson, 2016a); emergency response partnerships (Murray, 2015); restorative justice programs for both youth and adults (Bonta et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2009; Latimer et al., 2001); community safety and well-being action teams (Nilson et al., 2016); court diversion programs and problem-solving courts for both youth and adults (Werb et al., 2007; Hornick et al., 2005; Fischer & Jeune, 1987); Aboriginal partnerships (Hubberstay et al., 2014; Public Safety Canada, 2014); community safety teams (City of Calgary, 2010; Hogard, Elis & Warren, 2007; City of Edmonton, 2013); police prevention initiatives (Giwa, 2008; Dumaine, 2005; Walker & Walker, 1992); and multi-sector harm reduction programs (van der Meulan et al., 2016; Cooper et al., 2005; Kerr et al., 2005).

Within the policing sector, research has shown collaboration to improves outcomes in intimate partner violence (Kisely et al, 2010), police satisfaction (Corcoran et al., 2001), probation (Gibbs, 2001), offender re-entry (Bond & Gittell, 2010), and work with young offenders (Callaghan, et al., 2003; Erickson, 2012). Collaboration has been shown to nurture outcomes in other human service areas, including increased access to services and improved responsivity of those services to client needs (Gray, 2016; Clement, 2016; Cherner et al., 2014; Rezansoff et al., 2013); improved information sharing among participating organizations and greater interagency awareness (Gossner et al., 2016; Bellmore, 2013; Lipman et al., 2008); enhanced community/school engagement (Lafortune, 2015; Cooper, 2014); and, reduced risk/vulnerability of clients and families (Gray, 2016; Kirst et al., 2015; Augimeri et al., 2007).

3.3.2 Collaborative Models

Past analyses of multi-sector collaboration (Braga & Weisburd, 2012; Hayek, 2016; Przybyiski, 2008; Public Safety Canada, 2012; Stewart, 2016; Struthers, Martin & Leaney, 2009) have shown a growing reliance on partnerships to produce desired social change in Canadian communities. Compilations of the literature on criminal justice involvement in these models demonstrates increasing commitment toward social innovations at local, provincial and national levels (Nilson, 2018).

When it comes to human service professionals working collaboratively with Indigenous populations, there is also a growing understanding of traditional practices and protocol (Menzies & Lavallée, 2014). This, combined with the uptake of multi-sector collaboration in Canada, provides new opportunities to reduce or eliminate violence against Indigenous women (Chrismas, 2016; Muskoday Health Centre, 2012).

Literature (Taggart, 2015) on collaborative models in human service delivery show that successful intervention and prevention of violence requires a multi-system approach that addresses all of the conditions related to violence (e.g., racism, poverty, addictions). Addressing the various needs, interests, and barriers pertaining to violence invites a role for several interests to be involved. While social work professionals most often come to mind in violence intervention and prevention, there is an equally important role for health care practitioners (Thackeray et al., 2010), educators (Sundaram, 2014), spiritual leaders (Puchala et al., 2010), female survivors of violence (Wendt, 2013), and the police (Davis & Taylor, 2002).

While police hold the roles of enforcing laws through investigation, charge, and arrest, there are other ways the policing sector can contribute to violence prevention and intervention. In their research on effective solutions for violence against Aboriginal women in Australia, Davis and Taylor (2002) explain how among multiple important innovations, having police involvement at all levels was very important:

“It was about having a family violence intervention team who work with the police like a drug squad. They are housed away from the police station, there are three or four police officers involved, one being the DV liaison officer, three cops being part of the follow-up and two community-based workers, one Aboriginal and one non-Aboriginal woman…” (p.82).

In an attempt to assess their own involvement in multi-sector collaborative efforts to reduce violence against women, the RCMP (2017) completed an organization-wide scan of all models, initiatives, and projects that their members were involved in. Results of the assessment revealed the RCMP to be involved in at least 61 different types of collaborative activities. Among these 61 activities, all of them had occurred in more that once province or territory—with many being implemented across the country.

Each of these models identified through the RCMP assessment were grouped into one of four categories. Those considered to be policing, investigative and justice initiatives included examples like “Diversion Courts”, “Hub Model”, “Inter-Agency Violence Coordination”, “Risk Management Team”, and “MMIWG Family Liaison”. Those within the crime prevention category included examples such as “Aboriginal Shield Program”, “Band Engagement on Family Violence”, “Cadet Corps”, “Community Safety Plans”, “Moose Hide Campaign”, and “Working with MMIWG Groups”. Examples of collaborative training activities included “Bullying and Cyber-Bullying”, “Elder Safety”, “Family Violence and Historical Trauma”, “Girls Empowerment and Safety”, “Human Trafficking and Safety”, and “Suicide Prevention and Intervention”. Lastly, other initiatives included “Family Violence Initiative-Funded Projects”, “Indigenous-Specific Shelters” and “Protocols with Indigenous Organizations” (p.33-34).

In a recent national scan of 126 different multi-sector collaborative initiatives involving criminal justice professionals, Nilson (2018) examined the characteristics, purpose, design, intended outcomes, challenges, and benefits of each model. The author then organized these models into 20 groupings, which all fit into one of 6 approaches to community safety and well-being. To summarize these models, Table 4 provides a brief description of each grouping by approach.

APPROACH |

MODEL GROUP |

DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

Upstream Intervention |

Collaborative Risk-Driven Intervention |

Multiple human service providers meet weekly in a disciplined discussion forum to detect acutely-elevated risk, share limited information, and plan/deploy rapid multi-sector interventions before harm occurs. Situations are closed as soon as services are mobilized. |

Incident Response |

Police and Mental Health Crisis Teams |

Police officers partner with mental health crisis responders to respond to situations involving incidents stemming from mental health or addiction conditions. |

Police and Domestic Violence Teams |

Collaborative initiatives between police and a range of human service providers in the community that are implemented before, during, and after incidents of domestic violence. Child protection/family service workers may be deployed with police to respond to domestic/family violence calls. These specialized units are based on a coordinated model of specially trained police working in partnership with specially trained victim service workers from a community-based agency. |

|

Emergency Services Collaboration Teams |

Emergency services collaboration teams involve collaboration to enable emergency services - fire, police, and paramedic services – to more effectively share information and respond to emergency situations. |

|

Coordinated Support |

Service-Based Support Collaboratives |

A large group of initiatives involving collaboration between criminal justice professionals and other human service providers are defined as service-based supports. These initiatives mobilize service delivery from multiple sectors to support vulnerable individuals and families. In general, methods of needs assessment, care planning, and ongoing coordinated case management make up the activities in this model. Typically, service supports are coordinated until an individual or family stabilizes and can sustain their stability independent of support from human service providers. |

Integrated Police and Parole Initiatives |

The integrated police and parole initiative is designed to strengthen the link between branches of the criminal justice system by partnering corrections organizations with police services. The program uses a case management model of service delivery and consists of three components: comprehensive assessment of the offender’s circumstances including, but not limited to, a risk and criminogenic needs assessment; risk management interventions through supervision and other environmental structures; and risk reduction through rehabilitative interventions designed to reduce re-offending over time. |

|

Offender Reintegration Programs |

Offender reintegration programs involve collaborations between parole and community-based services (e.g., housing, vocational support, education) upon release of an offender to support successful re-entry into the community following a period of incarceration. |

|

Community Prevention |

Community Safety Teams |

Formal working partnership among police, fire, rescue, public health, housing, and emergency medical services to work with residents, businesses, and organizations to continuously assess and generate solutions to a broad array of community safety concerns such as underage drinking, drug houses, unsafe dwellings, etc. |

Police Youth Outreach Programs |

Police collaborate with youth services in the community to engage youth and develop a positive relationship with law enforcement. These types of programs may be targeted (e.g., programs for high-risk youth) or broader in nature (e.g., in-school programs). Youth outreach programs may involve partnerships with a wide range of community-based services to deliver programs that range from sports activities, art projects, drama productions, community cleanups, and hiking trips to leadership skills training. |

|

Aboriginal Partnerships |

Partnerships between the criminal justice system and local Aboriginal communities/services to ensure self-determination and promote healing and justice consistent with Aboriginal traditions and models of healing and wellness. |

|

Collaborative Community Prevention |

Collaborative community prevention initiatives are those programs in which criminal justice system representatives work with community-based services to deliver primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention activities in a community setting. These activities may be targeted (e.g., sexual offender programs) or broader (e.g., increasing officer visibility in public areas). |

|

Harm Reduction Programs |

Harm reduction programs involve criminal justice professionals to employ a health-centred approach that seeks to reduce health and social harms associated with drug use. |

|

Multi-Sector Cross Training and Education |

Criminal justice practitioners and professionals from other community-based services provide information and training to one another and/or receive joint training. Criminal justice professionals gain awareness of community resources and community needs, and other human service professionals gain knowledge of police and other criminal justice protocols. |

|

Community Safety Planning |

Involves a multi-sector process of assessing community needs, securing leadership support, mobilizing community assets, and developing a strategic plan to improve community safety. |

|

Collaborative Systemic Solution-Building |

Human service organizations partner to identify opportunities to improve the human service delivery system and address systemic problems through information sharing, data analysis, research, and consultation. |

|

Program-Based Prevention |

Program-Based Support Collaboratives |

A wide variety of group and individual-based programs designed to support vulnerable individuals and their families. The focus of these programs is largely to strengthen the resiliency of participants and reduce their risk factors for anti-social behavior. These programs can often involve participation and support of criminal justice professionals. |

Community Programs inIncarceration Facilities |

This model involves the delivery of community programs (e.g., vocational training, maternal support, trauma groups) to inmates who are incarcerated within the incarceration facility. Specially trained facilitators from community-based organizations deliver programs directly to the inmate population during their incarceration. |

|

Alternative Justice |

Restorative Justice Programs |

Restorative justice programs are collaborative community-based programs in which corrections works with other community services to manage minor domestic violence or drug offenses outside of the criminal justice system. Offenders must adhere to a set of conditions for participation and continued management of the issue outside of the court system, including participation in targeted community programming. Victims are also connected to appropriate services. |

Problem-Solving Courts |

Problem-solving courts (e.g. drug courts, domestic violence courts) offer a process to deal with a particular matter outside of the court system. Offenders are placed on a diversion plan outlining certain criteria (similar to probation) and program participation that must be completed to avoid a criminal record. Court diversion programs exist across Canada for both youth and adults. |

|

Youth Diversionary Programs |

Evidence-based process designed to divert moderate-risk youth from entering the criminal justice system. Validated screening and assessment tools are used by trained police officers to identify youth needs and risks. A multi-sector team of human service professionals conducts case planning, provides coordinated service delivery, and monitors youth performance until vulnerability subsides. |

(Source: Nilson, 2018:16-18)

Indigenous Models

Among the models featured in Nilson’s (2018) work, several were either implemented in Indigenous communities or designed to serve Indigenous populations. Some examples have been pulled from the larger work and are featured in Table 5 below.

MODEL NAME |

DESCRIPTION |

CITE |

|---|---|---|

Muskoday Intervention Circle |

Designed as a duo-enhancement to the Hub Model. In one way, the team works further upstream to support individuals before risks elevate. In another way, the team continues to collaborate after the intervention until client reaches a satisfactorily level of stabilization. |

Muskoday Intervention Circle (2015) |

Samson Cree Nation Hub |

Weekly meeting of multiple service providers focused on detection of elevations in risk, sharing of limited information, and rapid interventions designed to mitigate risk. |

Nilson (2016b) |

The Regina Intersectoral Partnership |

Shared assessment of client need; integrated coordination of support; ongoing barrier reduction; continuous trouble-shooting; and police involvement in mentoring, recreation and school engagement activities. |

TRiP (2016) |

British Columbia Indigenous Courts |

Developed in consultation with First Nations, speciality sentencing court brings together multiple stakeholders (including police) to plan support, healing and rehabilitation for the perpetrator and victims in the community. |

Provincial Court of BC (2019) |

Violence Against Women Case Review Project |

Human service and legal professionals collaborate with police to review cases of sexual assault to determine opportunities to improve how violence against women can be addressed by the legal system. |

OCTEVAW (2017) |

Risk Management Teams |

Collaboration among courts, police, human services, Elders, and community leaders to offer victims and perpetrators safety planning and service access. |

RCMP (2017) |

3.3.3 Key Ingredients

The central purpose of this report is two-fold: first, to identify key ingredients to effective police collaboration with Indigenous communities, and second, through this to contribute to a reduction in violence against women. Much of the literature reviewed in preparation of this report speaks to opportunities to build and strengthen good relations between police and Indigenous communities (Blagg, 2008; Human Sector Resources, 2004; Griffiths & Clark, 2017; Tyler, 2006). Some of this collaboration-related literature delves into opportunities to reduce violence against women (Griffiths & Clark, 2017; Jones et al., 2016; Puchala et al., 2010).

Earlier challenges for police and policy leaders include that for many years, despite the high importance placed on positive relationships between police and Indigenous communities, there was very little evidence around “what works” (Human Sector Resources, 2004). More recently, however, researchers (Chrismas, 2016; Jones et al., 2016; Nilson, 2018) have begun to assess several components of police-Indigenous relations to identify “what works” and “how”.

To begin, effective collaboration requires policing approaches to be driven through a “community policing” lens rather than “reactive enforcement” paradigm (Human Sector Resources, 2004). Initiatives built under such a framework must enhance Indigenous ownership and control over justice and justice-related processes (Blagg, 2018). Opportunities to achieve this include local governance structures like a police board or commission (Human Sector Resources, 2004). Others recommend recruitment strategies (Hylton, 2005), retention strategies for Indigenous officers (Cefai, 2005), community mentors (Griffiths & Clark, 2017), and cultural training (Palmater, 2016).

Next, police must secure community confidence (Myhill & Quinton, 2010) and legitimacy (Tyler, 2006). These ingredients can be secured when three things occur. The first is when police address problems that the community identifies as important to them (Mazerolle & Wickes, 2015). The second is when communities believe that authorities, institutions, and social arrangements are proper and just (Tyler, 2006). Lastly, the third is when it becomes clear that police and the community members share values (Griffiths & Clark, 2017).

To illustrate this process, Griffiths and Clark (2017) present a case study on police-Indigenous relations in the Yukon. Their findings reveal that the collaborative initiatives formed in the aftermath of several critical incidents significantly altered the dynamic between the police and Indigenous communities. Their case study illustrated that it is possible for large police organizations, in this case the RCMP, to adapt its policies and operations to better address the needs of the local communities it serves. In doing so, communities become a partner in addressing issues of crime and disorder.

A similar study of multi-sector collaboration was conducted in Samson Cree Nation, located in central Alberta. Results of the study (Nilson, 2016b) showed that police buy-in to the collaborative, shared ownership, and mutual commitments with other service providers, not only improved relationships between the RCMP and other service professionals, but between RCMP and the public. Indicators of success included more information-sharing with police, outreach for help from citizens, and reduced risk among target populations.

To offer some additional insight into key ingredients for effective collaboration between police and Indigenous communities, Jones et al., (2016) share several global themes from their review of community perspectives on policing in Saskatchewan. These include:

- Acknowledgement and identification of the reality of crime and public safety issues in these communities by the participants;

- The importance of the role of history, language, and culture when considering the administration of justice;

- The importance of police awareness and acknowledgement of the effects of intergenerational trauma resulting from the legacy of Canada’s colonial history, particularly the Indian Residential School System;

- The need for a more holistic approach to justice and policing centered on restorative values such as healing, helping, harmony, and balance that seeks to restore the community to a state of equilibrium rather than solely meeting legal concerns;

- The crucial importance of reciprocal mutual respect in relationships between the police and the community;

- The importance of collaborations between the police and community in addressing public safety issues;

- The need to embrace and incorporate a holistic approach by the police that moves significantly beyond a law enforcement paradigm;

- The flexibility to consider different logistical models of administering policing that reflect the individual circumstances of communities (i.e., integrated, self-administered).

(Jones et al., 2016:2-3)

Collaboration Ingredients to Reduce Violence

More specific to violence, key ingredients for police collaboration with Indigenous communities include community involvement in the design and delivery of justice and human service delivery (Blagg, 2008). Examples of this include police support for legislation that protects victims (Levan, 2003), online interventions (Rempel et al., 2019), harm reduction programs (Shannon et al., 2008), school and college-based interventions (Crooks, Jaffe & Kerry, 2019), spiritual programming (Puchala et al., 2010), and ‘women’s desks’ to handle harassment and domestic violence complaints (Perova & Reynolds, 2017).

In addition to community involvement, there also must be community commitment. According to Muskoday Community Health Centre (2012),

“A fair and pragmatic approach to changing social conditions—such as violence, addiction or poverty—requires long-term commitments of multiple partners. These partners must accept that working outside of their silos and collaborating their efforts is the only way to deliver an effective and sustainable solution to a social problem” (p.6).

With communities committed to collaboration, and committed to working innovatively, there is greater opportunity to identify the root causes of violence (Burnette, 2016). Understanding the root causes of violence better prepares collaborators to identify and mitigate the most pressing needs facing women, girls and their perpetrators.

In addition to community involvement and community commitment being required to reduce violence against women, the models themselves must be developed using insights from Indigenous women (Kurtz et al., 2013). Having the insight of Indigenous women properly informs narrative used within the partnership, and strengthens the relevance and overall outcomes of the service delivery model.

4.0 METHODOLOGY

To answer the questions driving this research project, a mixed methodology was employed. Each component of the methodology was designed to try and uncover knowledge on opportunities and key ingredients in establishing effective police collaboration within Indigenous communities. In total, there are five components of the methodology. These include: community interviews, subject matter expert interviews, model participant interviews, collaborative model analysis, and observation. To show how each question is pursued through this methodology, Table 6 shows the methods and data sources used to answer each question.

QUESTIONS |

METHOD |

DATA SOURCE |

|---|---|---|

1. What conditions or barriers contribute to increased vulnerability of women and girls to violence in Indigenous communities? |

a) literature review |

a) published; grey literature |

2. What police-related challenges impact efforts to reduce vulnerability and barriers to support for women and girls in Indigenous communities? |

a) literature review |

a) published; grey literature |

3. What opportunities are there for police to contribute to a reduction in vulnerability and barriers to support? |

a) literature review |

a) published; grey literature |

4. What past community experiences can we learn from to inform future directions for police-Indigenous community relations? |

a) literature review |

a) published; grey literature |

5. Moving forward, what are the key ingredients for effective collaboration among police, human service providers and Indigenous peoples? |

a) literature review |

a) published; grey literature |

6. What key features and characteristics of future police tools and resources would best contribute to a reduction in vulnerability to violence among Indigenous women and girls? |

a) literature review |

a) published; grey literature |

To better explain how the research team pursued answers to the research questions, the following sub-sections introduce each component of the methodology.

4.1 Community Interviews

The first part of the methodology included interviews with respondents from various Indigenous communities across Canada. Through a process of non-probability convenience sampling, respondents were identified through Internet and phonebook searches (Jager et al., 2017). In creating search parameters, the research team strived to achieve a broad-based sample of respondents. This involved outreach to Elders, community leaders, women exposed to violence, and a variety of human service stakeholders.

In total, 69 individuals were interviewed during the community interview component of this project. Interviews with community respondents were guided by the Community Interview Guide (see appendices). Interviews with community respondents lasted between 15 and 90 minutes. Responses were gathered in-person (n = 40) or over the phone (n = 29). Among the 69 individuals who received a request to be interviewed, only 4 refused to participate (response rate = 94%).

4.2 Subject Expert Interviews

The second part of the methodology involved interviews with individuals considered to be subject matter experts in the areas of family violence, social policy, policing, law, multi-sector collaboration, women’s health, Indigenous governance, research, and human rights. Respondents were identified in one of three ways. Some were identified during the literature review process and others were mentioned during planning consultations with the guidance cohorts. The remainder were identified by asking previous respondents who they suggested would be a relevant stakeholder to include (i.e., non-probability referral sampling).

In total, 29 subject matter experts were interviewed using the Stakeholder Interview Guide (see appendices). Most interviews were conducted either on the phone (n = 21) or in-person (n = 4). Each interview lasted between 30 and 120 minutes. A small number (n = 4) of respondents opted to answer the questions in writing and submit their responses to the research team electronically.

4.3 Model Participant Interviews

The third component of this methodology involved reaching out and interviewing actual participants of collaborative human service models in Indigenous communities that involve police. During the literature review, initial consultation, and collaborative model analysis portions of this methodology, several collaborative models of human service delivery were identified. The research team reached out and requested interviews with participants of the models. In total, all 47 model participants who received an interview request, agreed to be interviewedFootnote3.

Interviews with Model Participants lasted between 45 and 90 minutes. All were conducted either in-person (n = 32), through video conference (n = 14), or over email (n = 1). Interviews with Model Participants were led by the Model Participant Interview Guide (see appendices). Due to the sensitive nature of some topics covered in this research, model participants and their models were promised anonymity in the results write-up.

4.4 Collaborative Model Analysis

The fourth part of the methodology involves analysing existing collaborative models for opportunities and challenges concerning police involvement in these models. During both the literature review and preliminary consultations conducted during the planning stages of this project, the research team looked for existing multi-sector human service models being implemented in Indigenous communities. The purpose of this exercise was to learn about effective police participation in these models. In particular, the analysis was designed to examine three topics of police involvement in multi-sector collaborative models: a) police preparation for participating in the model; b) common challenges of police while engaged in the model; and c) maintaining effectiveness while engaged in the model.

4.5 Observation

The final component of the methodology involved naturalistic observation of some of the collaborative human service models included in this research. Through model contacts made during the consultation stage, arrangements were made for the research team to observe some of the core components (i.e., meetings) of the collaborative models. During the observation process, the research team captured notes on a variety of themes, including: synergy, teamwork, communication, process, discipline, roles, challenges, and main characteristics. In total, 3 different opportunities for observation were made available to the research team. These include observations of Samson Cree Nation Hub, Muskoday Intervention Circle, and English River Intervention and Support Circle.

5.0 RESULTS

Data collected for this evaluation were analysed in October and November of 2019. Results are presented by each individual method used to capture data. The first set of results presented are those stemming from interviews with Indigenous community leaders, Elders, human service professionals, women exposed to violence, and community members. The second set of results stems from data gathered during interviews with subject matter experts. The third set of results derives from interviews with participants of Indigenous collaborative models involving police. The fourth set of results involve a model analysis completed using data from the interviews and literature review. The final set of results includes observations made by the research team.

5.1 COMMUNITY INTERVIEWS

During the research project, 69 individuals from Indigenous communities agreed to take part as interview respondents. Respondents in this group included a wide variety of community leaders, Elders, human service professionals, women exposed to violence, and community members. In total, 46 of these interviews were with First Nation respondents, 21 of these interviews were with Métis respondents, 1 interview was with an Inuit respondent, and 1 interview was with a non-Indigenous respondent working for an Indigenous organization. While most interviews were conducted individually, one group interview with 17 human service providers from different professional backgrounds was facilitated Footnote4. Regionally, respondents came from Indigenous communities in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Nunavut. To show you the sectors engaged in this process, Table 7 shares the number of respondents by sector/role.

SECTOR/ROLE |

N |

% |

|---|---|---|

Accreditation |

1 |

1.4 |

Addictions |

3 |

4.3 |

Business Owner |

3 |

4.3 |

Bylaw |

1 |

1.4 |

Corrections |

3 |

4.3 |

Culture and Spirituality |

3 |

4.3 |

Early Childhood Development |

2 |

1.4 |

Education |

6 |

10.1 |

Elder |

4 |

5.8 |

Employment Support |

1 |

1.4 |

Family Violence |

5 |

7.2 |

Healthcare |

4 |

5.8 |

Housing |

3 |

4.3 |

Income Assistance |

3 |

4.3 |

Justice |

3 |

4.3 |

Leadership (Chief, Council, President) |

9 |

13.0 |

Mental Health |

2 |

2.9 |

Police |

1 |

1.4 |

Post-Secondary |

3 |

4.3 |

Sports and Recreation |

3 |

4.3 |

Women Exposed to Violence |

6 |

8.7 |

Police Partnerships

The first question on the survey asked respondents how they would describe their relationship with police in the community. This was a fixed response question that offered three possible answer choices: ‘not good’, ‘ok’, and ‘good’. Results show that a majority of respondents described the relationship with police in their community to be either ‘ok’ (42.1%) or ‘good’ (47.8%) (see Table 8).

RESPONSE |

N |

% |

|---|---|---|

Not Good |

7 |

10.1 |

Ok |

29 |

42.1 |

Good |

33 |

47.8 |

The second question asked respondents whether the police partner with any organizations in their community. This was also a fixed response question with three possible answer choices: ‘they do not’, ‘I do not know’, and ‘yes they do’. Results of the analysis show that most (63.5%) of respondents answered ‘yes they do’. In contrast, only 23.1% felt police did not partner with others, and 13.5% reported that they ‘did not know’ (see Table 9).

RESPONSE |

N |

% |

|---|---|---|

They do not partner |

15 |

21.7 |

Do not know |

11 |

15.9 |

Yes, they do partner |

43 |

62.3 |

As a follow-up to the previous question, if respondents reported that police did partner with organizations in their community, they were asked to explain the type of partnership. Feedback from respondents identified a few different observations. Some of the more common responses include inter-agency meetings, neighbourhood watch, school presentations, awareness walks, Aboriginal Shield, search and rescue, the Hub Model, and problem-solving teams. To provide further insight, Table 10 divides responses between partnership models or initiatives and partnership gestures or activities.

PARTNER TYPE |

EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

Model/Initiative |

|

Activity/Gesture |

|

Good Relations

The next question asked respondents what they believe makes for a good relationship between police and the community. Table 11 groups some of the more common suggestions into themes. These include communication, action, presence, effort, engagement and approach.

THEME |

SUGGESTIONS |

|---|---|

Communication |

|

Action |

|

Presence |

|

Effort |

|

Engagement |

|

Approach |

|

Bad Relations

In contrast to the last question, respondents were asked to identify what makes for bad relations between police and the community. As Table 12 indicates, feedback from community-level respondents identify some challenges around inaction, process, lack of knowledge, absence, opinion, and negative attitude.

THEME |

SUGGESTIONS |

|---|---|

Inaction |

|

Process |

|

Lack of Knowledge |

|