National Security Transparency Advisory Group Initial Report : What We Heard In Our First Year

The National Security Transparency Advisory Group (NS-TAG) is an independent, arms-length committee that is supported financially and in-kind by the Government of Canada.

The opinions and views expressed in this document are strictly those of the NS-TAG members collectively, and should not be considered as the official view of the Government of Canada.

Initial Report to the Deputy Minister of Public Safety Canada on Transparency in National Security

Table of contents

- Introduction: The First National Security Transparency Advisory Group (NS-TAG) Report

- What We Heard in Our First Year

- Governance within the National Security Community

- Reflexive Secrecy

- Digital and Open Government

- Secrecy in Oversight Mechanisms and Legal Proceedings

- Information Management

- Privacy and Security

- Relationships with Racialized, Marginalized and Other Minority Communities

- Workplace Culture in National Security Agencies

- How the Government Communicates

- The Way Ahead

- Annex 1: Background on National Security Transparency

- Annex 2: Background on the National Security Transparency Advisory Group (NS-TAG)

- Annex 3: National Security Community Architecture

- Annex 4: NS-TAG Meeting Highlights, August 2019-September 2020

- Annex 5.1: International Jurisdictional Scan of Transparency in National Security

- Annex 5.2: Transparency Policies in National Security and Intelligence in Selected Governmental Organizations at the International Level

- Footnotes

Introduction: The First National Security Transparency Advisory Group (NS-TAG) Report

The national security community in Canada has traditionally not been very transparent. Official websites and public documents typically contain little information, while the access to information system is frequently criticized for the severe extent of its redactions and its slow processes. The situation has somewhat improved in recent years, notably through the establishment of the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians (NSICOP) and of the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA). The establishment of both review bodies have led to the enhanced review and oversight of Canada’s national security and intelligence community.

In a 2020 survey, 49% of Canadians expressed some degree of agreement that “I can trust the Government of Canada to strike the right balance between security and civil liberties.” In 2017, this percentage was 55%.

Source: Library and Archives Canada – Public Opinion Research Report 063-19.

As the National Security Transparency Advisory Group (NS-TAG), our work in the past year has convinced us of the need to continue improving national security transparency. We certainly understand that some information held by national security institutions must remain classified. At the same time, transparency is essential to the health of a democracy. Law enforcement and intelligence agencies need to be perceived as legitimate by the society they seek to protect: when they have the trust of the population, it is easier to develop ties with communities. Transparency can also ensure that national security professionals are held to account when transgressions arise. When agencies do not believe they will be held to account, inappropriate actions and behaviours continue to go unaddressed; yet when security agencies are too secretive and closed, it is more difficult for citizens to trust them. This reinforces a dynamic of mistrust and suspicion.

What We Heard in Our First Year

The main themes we explored during our first year of work include: governance within the national security community; the prevalence of reflexive secrecy; challenges associated with digital and open government; secrecy in oversight mechanisms and legal proceedings; information management; the difficult balance between privacy and security; the national security community’s relationships with racialized and other minority communities; the link between transparency and workplace culture in the community; and, finally, the more technical issue of how the government communicates.

Governance within the National Security Community

Over the course of three in-person meetings and several more virtual meetings, we heard from a range of officials from the national security community about their views on transparency. A number of challenges emerged. First, size matters: we recognize that the national security community is large. This raises important challenges in terms of coordination; improving transparency requires efforts that take time and can only be achieved through the mobilization of significant will. As a result, coordination – the alignment of multiple moving pieces – is complex. The national security community faces multiple challenges at this level, including in terms of its leadership: both the National Security and Intelligence Advisor to the Prime Minister (NSIA) in the Privy Council Office, and the Deputy Minister of Public Safety, have a coordinating role, but the precise distribution of their responsibilities is not always clearly defined. Second – a topic we will look into during our second year – definitional issues also matter: more transparency has different implications for different agencies.

It would be useful if the government could better explain these complexities in straightforward and engaging ways to enable the public to have a better grasp of national security issues. This could be done through more regular public speeches by elected officials and senior public servants, as well as more frequent and better official written communications through websites, social media, and reports. Importantly, better transparency here is not solely a matter of quantity. More communication is necessary, but it should also be clear, digestible, and meaningful. The government could also be more transparent in communicating the possible points of interactions between the public and the national security community, notably to hold it accountable (e.g., complaints mechanisms, ombudspersons, etc.). We have also heard various points of view regarding potential shifts in the scope of national security, border management, and intelligence capacities in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Going forward, we intend to give consideration to the potential implications for governance and transparency from these recent developments.

Reflexive Secrecy

In the national security community, there is a dominant reflex to keep information as secret as possible; the default position is usually to protect information. While this is sometimes necessary, efforts to improve transparency need to be accompanied by changes to this culture of secrecy. This is not a new problem. A decade ago, the Air India inquiry emphasized that one of the biggest institutional failings that led to the tragedy was a systemic lack of information-sharing among government agencies.Footnote1 The norm that information should be shared on a “need-to-know” basis is often interpreted too stringently; instead, as many of our guest speakers argued, the national security community needs to be more disciplined and rigorous in avoiding the systematic over-classification of data.

This lack of transparency can have unintended consequences, as the information gap is more likely to be filled with misinformation or raise suspicions. In an era of an abundance of online information, some of which is available through open sources or from Canada’s allies, the lack of government disclosure can raise suspicion.

Transparency is often one of the last priorities in national security discussions, but there is growing recognition of the need for systemic reforms to change this. In 2018, for example, the U.S.-based RAND Corporation published a report titled “Secrecy in US National Security: Why A Paradigm Shift is Needed.”Footnote2 The report makes the case for systemic change in governance structures and mindsets in order to improve both accountability and performance. Many of the themes in this report are closely aligned with feedback we heard from stakeholders in our own discussions.

Digital and Open Government

As digital and open government reforms have expanded in recent years, there has been growing recognition of the benefits stemming from information sharing within and outside of government, and of engaging citizens in meaningful ways. The Government of Canada has taken a number of measures to improve its performance, such as: the proactive disclosure of information; the quantity and quality of open data; and, the engagement of the public in a range of policy issues, notably through its commitments to the Open Government Partnership.Footnote3 In spite of this progress, much work remains to be done. A 2016 report on Digital Government and Westminster governance reforms by the University of Toronto’s Mowat Centre observed, for example, that public servants are incentivized to hoard scarce and specialized information rather than share it.Footnote4 As the report noted, echoing many of the insights from the aforementioned RAND study, changing this mindset can only result from a large-scale cultural shift.

Change must come both from the top – leaders can and should be more open and transparent – and from the bottom, notably through better training and awareness. This is an important point. At least one of our guest speakers emphasized that merely directing lower-level personnel in government to be more transparent is not sufficient; management must provide them with the necessary tools and skills to do so. Finally, we note that transparency efforts also require financial investments in human resources, technology to support transparency measures, and engagement activities. Absent these additional, specifically designated resources, new transparency initiatives merely add to the workload of public servants.

Secrecy in Oversight Mechanisms and Legal Proceedings

Secrecy surrounding national security oversight mechanisms and legal proceedings is another area in which added transparency is crucial in fostering public trust. Even in ordinary criminal and civil legal proceedings, the open court principle has limits. National security proceedings are no exception. Nevertheless, maximizing transparency by national security review and oversight bodies and legal proceedings could assist in reducing suspicion and the trust deficit.

In our first year, we received representations about the need for more transparency on how mandates and authorities of national security organizations are legally interpreted and implemented. Related to this is the issue of legal interpretations that arose in a recent public decision of the Federal Court.Footnote5 The Court found that due to institutional failings by both the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the Department of Justice, CSIS breached the duty of candour owed to the Court in failing to proactively identify and disclose that it had included information, in support of warrant applications, that was likely derived from illegal activities. In 2013Footnote6 and 2016Footnote7, the Federal Court had also found breaches of the duty of candour by CSIS involving warrant applications.

National security review organizations also face the challenge of balancing the importance of transparency with the need for secrecy when carrying out their responsibilities. In 2017, a former national security review organization, the Security Intelligence Review Committee (SIRC, now replaced by NSIRA), dismissed a complaint against CSIS and sought to restrain the ability of the complainant to comment on it publicly by issuing a “confidentiality order.”Footnote8 The Federal Court later allowed the disclosure of the unclassified SIRC record stating that “to find otherwise would be to routinely subordinate the open court principle to the practices of any tribunal authorized to conduct its hearings in private.”Footnote9

Information Management

Throughout our first year, we heard about a number of challenges in the information management realm that impede efforts to enhance the national security community’s transparency. Canada, in particular, does not have a comprehensive declassification strategy, which often significantly hampers the release of older classified documents. The access to information process is widely criticized for being painstakingly slow, and documents tend to be released only once they have been excessively redacted. In addition, different government departments and agencies work with a range of technologies and information management systems. Many of these do not speak easily to one another, complicating the sharing of information within government, between security bodies, and to the general public. Previous reform efforts have often failed to lead to more than incremental change.

Privacy and Security

In a 2019 survey, 92% of Canadians expressed some level of concern about the protection of their privacy.

Source: Library and Archives Canada – Public Opinion Research Report 055-18.

As governments gather and process data and information from a broadening range of sources, many have raised concerns about risks to personal privacy. Transparency in terms of how national security agencies access, share, and analyze data involving the identities and actions of members of the public is essential, as many stakeholders noted (including the Privacy and Information Commissioners of Canada). New tools stemming from Artificial Intelligence and mobile device applications create greater opportunities for enhancing security capacities while also deepening questions about privacy protections. Through advancements in machine learning, there are added concerns that metadata may reveal information about people in ways that reinforce discrimination and biases. Predictive analytics is a seductive tool, but can lead to undesirable outcomes that hurt already marginalized communities. Although many laws exist protecting the privacy rights of people living in Canada, these rights are challenged by national security legislation that may limit or override them, which makes striking an appropriate balance between openness and secrecy imperative. We also engaged with various experts on the privacy and security implications of COVID-19 contact tracing applications for mobile phones, an important example of how public health surveillance, national security, and data governance can become further intertwined and consequently heighten matters of privacy, security, and transparency.

In a 2018 survey, 41% of Canadians expressed concerns about the information that intelligence agencies collect on them.

Source: Library and Archives Canada – Public Opinion Research Report 101-17.

Safeguarding privacy also requires secure infrastructure for storing and sharing data, a growing challenge for all sectors as massive cloud-based systems expand and underpin online activity. Along with its own systems, governments also face external privacy challenges tied to encryption, which can improve privacy protections on one hand while also facilitating nefarious activities and emerging threats on the other. Creating modern and innovative cybersecurity capacities to address the various competing facets of encryption is an emerging priority for national security agencies that is closely interwoven with matters of transparency, as well as the aforementioned structures and cultures of reflexive secrecy that can impede progress in this regard. In addressing these challenges, it will be vital to ensure that transparency is not forsaken in the name of privacy and security. This necessitates creative technological solutions and requires continued work with the international community on open data standards and solutions.

Relationships with Racialized, Marginalized and Other Minority Communities

National security agencies must acknowledge that systemic racism and unconscious biases exist within them, and that these biases are manifested in their interactions toward certain members of the public. If national security agencies do not recognize and vigorously address these existing biases, they risk individually or collectively failing to detect, and act upon, actual dangers posed to society.

What information are national security agencies allowed to collect, who can they share it with, and what is appropriate and legal? Agencies often poorly answer these questions, and this lack of transparency feeds mistrust and suspicion. This further damages a sense of belonging, social cohesion, and public safety for all. As one of our guest speakers emphasized, many members of Indigenous, Black, racialized, marginalized, and other minority communities mistrust national security agencies, and the nature of their interactions with these government bodies often exacerbate these tensions.

It is essential for national security agencies, when they interact with people of all communities, to better inform the public about their mandates, responsibilities and authorities, and about the community’s or individual’s rights. They could also be more attuned to the reality that some people living in Canada, be they Canadians or not, have prior negative histories with state authorities in Canada and other countries that may shape their perceptions of Canadian security agencies. As we intend to explore in the second year of our work, enhancing diversity and inclusion in the personnel practices of national security agencies is essential to prevent mistreatment and exclusionary practices. This includes engaging in anti-racism and unconscious bias training for all levels of personnel and being more aware of the experiences of racialized, marginalized, and other minority communities within the agencies.

When it comes to national security, members of Indigenous, Black, and other racialized communities may have formed a certain perception of how national security agencies conduct their business. In an effort to be more transparent, national security agencies can be more responsive to communities’ repeated calls for accountability, address their concerns, and respond to their requests. There is also an opportunity for national security agencies to take accountability where there might have been a lack of transparency in the past. This requires a commitment to meeting communities where they stand.

Members of these communities sometimes fear that national security agencies contact them to gather intelligence under the name of outreach; it is therefore important for national security agencies to be fully transparent about their work. Is there really a need for outreach? What are an individual’s rights with regards to interactions like this? These rights should be identified clearly and without coercion prior to any further communication with an individual. National security agencies must also practice caution around the content and delivery of their training (which includes, but is not limited to, countering violent extremism and counter-terrorism). They must, in particular, make sure that training does not target or label any specific community. The stigmatizing content and delivery of their training programs has harmed trust in federal agencies and has contributed to feelings of unease and skepticism towards them.

Finally, the use of stigmatizing words or labels about a community or religion in national security reports has negatively affected interactions between local law enforcement and the public as it makes communities feel targeted. Even though different levels of organizations (municipal, provincial, and federal) have their own respective mandates, the actions of one can affect others, as many members of the public perceive all these levels under the same umbrella.

Workplace Culture in National Security Agencies

There have been a number of stories reported in the media in recent years on cases of harassment and discrimination in national security agencies. These government bodies produce public reporting explaining where such problems arose and how they were dealt with, yet they typically include only limited information. How frequent are such cases, and how can the public be confident that serious efforts are made to improve the situation? How do such problems affect these agencies’ relations and trust with racialized and other minority communities? We believe that part of our role as the NS-TAG is to help bring attention to these issues and to explain how a lack of transparency can feed mistrust.

How the Government Communicates

In a 2017 survey, “on an unaided basis, only 3% of respondents correctly name “CSE” or the “Communications Security Establishment” as the government agency responsible for intercepting and analyzing foreign communications and helping protect the government’s computer networks. The Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) is much more commonly named as the agency described (mentioned by 22%).”

Source: Library and Archives Canada – Public Opinion Research Report 128-16.

Well-intentioned government efforts at being transparent are often undermined by ineffective communications: for example, officials sometimes do not know who to reach out to, while documents and public statements – in particular on government websites – tend to use dry or technical language, making the information less engaging for the public. That is, improving transparency is not only about being more transparent, but also about improving how transparency is implemented in practice. This is an especially important issue for interactions with marginalized and racialized communities, where biases, translation challenges, or intercultural misunderstandings can hamper effective communication.

We believe that the government’s interactions with the media are an especially important, yet sometimes neglected, part of the equation. The government sometimes interacts directly with members of the public, either in person or through various reports, statements, and websites. But government information also often reaches the public after being filtered by the media; efforts to enhance transparency should therefore include initiatives to better leverage the media’s role, notably by offering improved information sessions. This is true for national and mainstream media, but also for local news outlets, and especially those that serve racialized and minority communities.

The Way Ahead

The NS-TAG will produce two reports in its second year (2020-2021). The first, to be released in the first half of 2021, will focus on the definition, measurement, and institutionalization of transparency. There are multiple definitions of transparency, in national security and beyond, and it is difficult to measure. Yet having a foundational understanding of what transparency is, how to measure it, and how to assess progress is essential to efforts to improve it. We therefore propose to dive deeper into these questions. At the same time, for enhanced transparency to be sustainable, it must be institutionalized and routinized. Structures and processes must be put in place to “hardwire” transparency into the national security community’s everyday work. The report will also examine the evolution of open government in light of the COVID-19 pandemic as we seek to understand the potential implications for government transparency generally – and the National Security Transparency Commitment specifically – in light of this new reality.

The second report, to be released later in 2021, will study relations between national security agencies (especially the RCMP, CSIS, and the CBSA) and racialized and other minority communities. For this, we will reach out to a range of individuals and organizations from various communities in year two, as well as from the agencies themselves.

Annex 1: Background on National Security Transparency

What is Transparency and Why is it Important for National Security?

Members of the public need to have confidence in national security efforts to maintain the Government’s operational effectiveness, democratic resilience, and institutional credibility. The Government has a duty to foster this confidence by providing the public with relevant and timely information on national security and related intelligence activities to enable civic engagement in the development of national security policies and activities, and to ensure public accountability.

For additional precisions on what national security is and the national security architecture, please see Annex 3.

The National Security Transparency Commitment

The National Security Transparency Commitment was announced in 2017. The aim of the Commitment is to enhance Canada’s democratic accountability by explaining to the public what the Government of Canada does to protect national security, how the government does it, and why this work is important.

The National Security Transparency Commitment identifies six guiding principles for national security transparency, categorized into three broad areas:

Information Transparency

- Departments and agencies will release information that explains the main elements of their national security activities and the scale of those efforts.

- Departments and agencies will enable and support Canadians in accessing national security-related information to the maximum extent possible without compromising the national interest, the effectiveness of operations, or the safety or security of an individual.

Executive Transparency

- Departments and agencies will explain how their national security activities are authorized in law and how they interpret and implement their authorities in line with Canadian values, including those expressed by the Charter.

- Departments and agencies will explain what guides their national security-related decision making in line with Canadian values, including those expressed by the Charter.

Policy Transparency

- The Government will inform Canadians of the strategic issues impacting national security and its current efforts and future plans for addressing those issues.

- To the extent possible, the Government will consult stakeholders and Canadians during the development of substantive policy proposals and build transparency into the design of national security programs and activities.

The Commitment was introduced following input received through the 2016 National Security Consultations.Footnote10 These extensive consultations engaged Canadians, stakeholders, and subject-matter experts on issues relevant to national security, including oversight and accountability. Across a span of four months, Canadians provided 58,933 responses to an online questionnaire and submitted 17,862 emails. They also participated in public town halls, engagement events held by Members of Parliament, in-person sessions, digital events, and one round-table.Footnote11 Many responses noted a perceived lack of transparency, as well as distrust in Canada’s national security institutions and law enforcement.

The National Security Act, 2017

Also arising from the national security consultations was Bill C-59, now known as the National Security Act, 2017. The Act established several key initiatives meant to promote national security transparency, including the introduction of a new, comprehensive national security review body called the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency and the appointment of an Intelligence Commissioner. The legislative approval of the Act gave the Commitment, a related initiative, credence and momentum to begin implementation in earnest.

The aim of the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency is to ensure that the historic and ongoing work of Canada’s national security institutions are reasonable, necessary, and in line with Canadian law.Footnote12 The National Security and Intelligence Review Agency acts independently to determine which government activities to review, and has the ability to access information from any department or agency with national security responsibilities across government.Footnote13 It collaborates with the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians, which also has a broad mandate to review the Government of Canada’s national security and intelligence institutions.

The Intelligence Commissioner conducts an oversight function by independently reviewing and authorizing certain intelligence activities before they are performed. This oversight applies to the Canadian Security Intelligence Service and the Communications Security Establishment.

The National Security Transparency Commitment does not come with review or oversight mechanisms, but rather calls upon departments and agencies with national security responsibilities to proactively share information related to their work and engage regularly with the Canadian public. In this way, the Commitment supports the work of other transparency initiatives - including the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency, the Intelligence Commissioner, the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians, the Privacy Commissioner, the Information Commissioner while making information more accessible to Canadians.

Annex 2: Background on the National Security Transparency Advisory Group (NS-TAG)

An essential component of implementing the National Security Transparency Commitment is the National Security Transparency Advisory Group (NS-TAG). The NS-TAG is an external advisory group whose mandate is to provide advice to the Deputy Minister of Public Safety (and by extension, other national security related departments and agencies) on the effective implementation of the Commitment. The annual report is the NS-TAG’s primary mechanism for dispensing advice.

The NS-TAG was established to provide advice on how toFootnote14:

- Infuse transparency into Canada’s national security policies, programs, best practices, and activities in a way that will increase democratic accountability;

- Increase public awareness, engagement, and access to national security and related intelligence information;

- Promote transparency while ensuring the safety and security of Canadians.

Minister of Public Safety Ralph Goodale officially launched the NS-TAG in July 2019. Members were selected to represent a diversity of experience and expertise in academia, civil society and the public service, in subject areas including national security, open government and human rights. The NS-TAG government co-chair is determined by the Deputy Minister of Public Safety. The Non-government co-chair is selected by the Group. The former exists to act as a bridge between the government and the NS-TAG, and liaise with national security departments and agencies as necessary.

NS-TAG Meetings

The NS-TAG is mandated to meet up to four times per fiscal year to discuss issues of transparency, hear from guest speakers, and develop their advice to the Deputy Minister. For more information on the NS-TAG’s mandate, membership, and meetings, please refer to the Group’s Terms of Reference.Footnote15

Between summer 2019 and winter 2020, the NS-TAG met three times in-person. Their fourth meeting was planned for late March 2020, but as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was replaced with a series of three virtual meetings, which took place throughout the summer of 2020.

Initial meetings focused on presentations from government officials on the roles and responsibilities of key national security institutions. Representatives from relevant review and accountability bodies were invited to help situate the NS-TAG within the broader national security transparency and accountability environment.

As meetings progressed, the NS-TAG also heard from members from civil society, including experts in national security law, representatives from human rights organizations, journalists, and technology professionals from the private sector. Several themes were addressed, from diversity and inclusion in national security institutions to privacy implications when addressing digital threats. For a more detailed overview of topics discussed, please refer to the chart in Annex 4.

Members of the NS-TAG as of October 7, 2020.

- William Baker, Chair of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada Departmental Audit Committee, Former Deputy Minister of Public Safety Canada

- Khadija Cajee, Co-Founder, No Fly List Kids

- Mary Francoli, Director, Arthur Kroeger College of Public Affairs, and Associate Dean, Faculty of Public Affairs

- Harpreet Jhinjar, Expert in Community Policing and Public Engagement

- Thomas Juneau (non-governmental co-chair), Associate Professor at the University of Ottawa's Graduate School of Public and International Affairs

- Myles Kirvan, Former Associate Deputy Minister of Public Safety Canada, former Deputy Minister of Justice and Deputy Attorney General of Canada

- Justin Mohammed, Human Rights Law and Policy Campaigner at Amnesty International Canada

- Bessma Momani, Professor of Political Science at the University of Waterloo and Senior Fellow at the Centre for International Governance and Innovation

- Dominic Rochon (government co-chair), Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, National and Cyber Security Branch, Public Safety Canada

- Jeffrey Roy, Professor in the School of Public Administration at Dalhousie University’s Faculty of Management

The term of NS-TAG membership is two years with the possibility of a one-year renewal.

Annex 3: National Security Community Architecture

What is National Security?

There is no recent, official definition of ‘national security’ by the Government of Canada. The last National Security Policy, 2004’s Securing an Open Society, focused on the following broad national security issues:

- Protecting Canada and Canadians at home and abroad;

- Ensuring Canada is not a base for threats to our allies;

- Contributing to international security.

In today’s evolving landscape, national security activities are continuously adapting to keep pace with new and emerging threats from terrorism and violent extremism, to disinformation campaigns during election season, to cyber hacks targeting government databases.

National Security Departments and Agencies in Canada

The Government relies on a number of departments and agencies to identify and address national security threats. While many federal departments and agencies have some national security responsibilities, the primary or core institutions that make up Canada’s national security community include:

Canada Border Services Agency: Provides border services that support national security and public safety priorities and facilitates the free flow of persons and goods.

Canada Security Intelligence Service: Investigates suspected threats to the security of Canada and reports to the Government of Canada, sometimes taking steps to reduce these threats.

Communications Security Establishment:Collects foreign signals intelligence and helps protect the computer networks and information of greatest importance to Canada.

Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces: Supports the Canadian Armed Forces who serve with the Navy, Army, Air Force and Special Forces to defend Canada’s interests at home and abroad.

Global Affairs Canada: Has the mandate for foreign policy, diplomatic representation and foreign intelligence, and provides reporting on a range of international security issues.

Integrated Terrorism Assessment Centre: Analyses terrorism threats to Canada and Canadian interests and recommends the National Terrorism Threat Level.

Public Safety Canada: Coordination of national security policy (crime, terrorism, cyber, critical infrastructure), emergency response, responsible for portfolio agencies – RCMP, CSIS, CBSA, Correctional Services.

Privy Council Office: The Security and Intelligence Secretariat, the Intelligence Secretariat and the Foreign and Defence Policy Secretariat are part of the Privy Council Office and serve an important role in the coordination of strategic decision-making on national security matters.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police: Prevents and investigates crimes, enforces the law, and strives to keep the public safe at the community, provincial/territorial and federal levels.

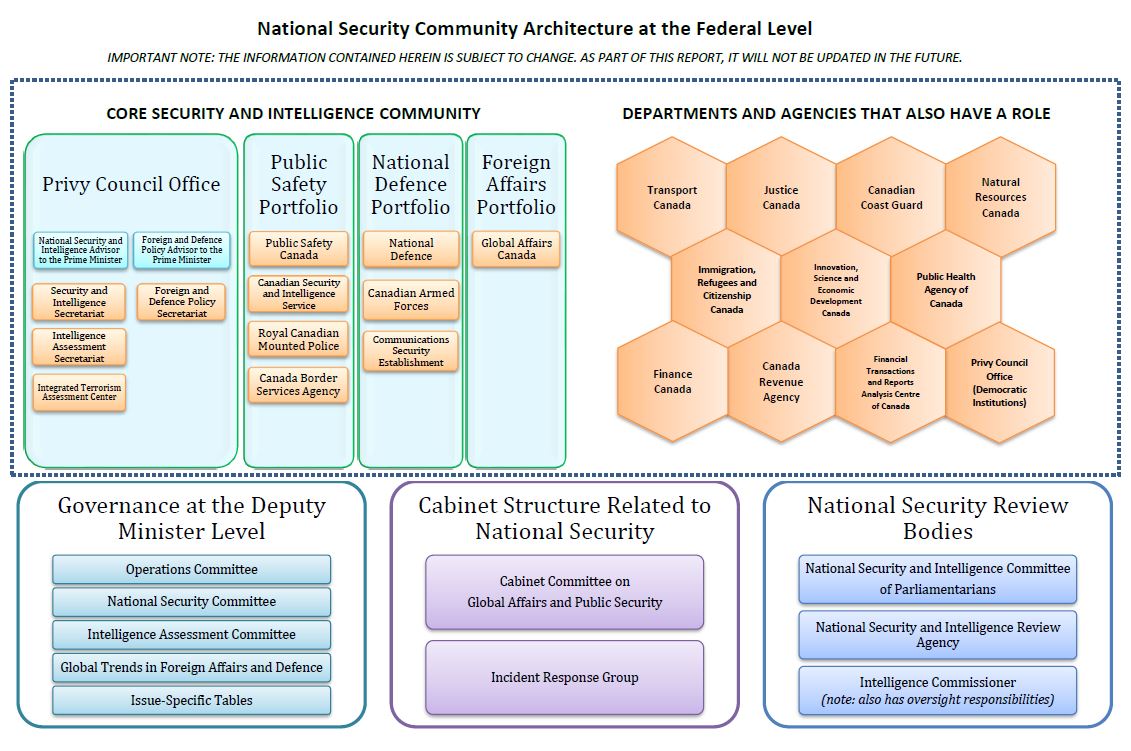

National Security Community Architecture at the Federal Level

Image Description

Core Security and Intelligence Community

Privy Council Office

- National Security and Intelligence Advisor to the Prime Minister

- Security and Intelligence Secretariat

- Intelligence Assessment Secretariat

- Integrated Terrorism Assessment Center

- Foreign and Defence Policy Advisor to the Prime Minister

- Foreign and Defence Policy Secretariat

Public Safety Portfolio

- Public Safety Canada

- Canadian Security and Intelligence Service

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- Canada Border Services Agency

National Defence Portfolio

- National Defence

- Canadian Armed Forces

- Communications Security Establishment

Foreign Affairs Portfolio

- Global Affairs Canada

Departments and Agencies that also have a role

- Transport Canada

- Justice Canada

- Canadian Coast Guard

- Natural Resources Canada

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- Finance Canada

- Canada Revenue Agency

- Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada

- Privy Council Office (Democratic Institutions)

Governance at the Deputy Minister Level

- Operations Committee

- National Security Committee

- Intelligence Assessment Committee

- Global Trends in Foreign Affairs and Defence

- Issue-Specific Tables

Cabinet Structure Related to National Security

- Cabinet Committee on Global Affairs and Public Security

- Incident Response Group

National Security Review Bodies

- National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians

- National Security and Intelligence Review Agency

- Intelligence Commissioner (note: also has oversight responsibilities)

Annex 4: NS-TAG Meeting Highlights, August 2019-September 2020

Meeting 1 – August 22-23, 2019, Ottawa

Theme/Topic:

Internal Discussion

- National Security Transparency Commitment (NSTC) briefings.

- Discussion on creating an online source for publically accessible national security information that is interesting, useful and accessible to Canadians.

- Need for a cultural change within government to support future transparency efforts.

- Discussion on National Security and Intelligence Review Agency, Open Government Partnership Global Summit 2019, and national security transparency practices across the Five Eyes.

Theme/Topic:

Discussion with Public Safety Deputy Minister

- Enhanced efforts to explain domestic national security and intelligence activities would help dispel myths and misinformation within the public regarding these activities.

Theme/Topic:

Discussion on Open Government

- The importance of public engagement in government decisions, both in person and online.

- Provided insight on the Open Government’s Multi-Stakeholder Forum’s meeting cycle, performance indicators and reporting mechanisms, and how ongoing engagement and discussion is needed to sustain these types of advising bodies.

Theme/Topic:

Discussion with the CSIS and CSE

- Increasing transparency within CSIS and CSE in response to public need and in better addressing information gaps.

- Discussion on the organizational culture of both CSE and CSIS, the role of the media in communicating issues of national security, the existing knowledge gaps on issues of national security, and the public’s perception and experience of Canada’s national security activities.

Meeting 2 – December 1-2, 2019, Ottawa

Theme/Topic:

Internal Discussion

- Provided guidance on the recruitment of a new member following the recent resignation of Michel Fortmann.

- Considered the creation of sub-groups for tasks moving forward.

- Aim to produce a report following the fourth meeting in March 2020.

Theme/Topic:

Discussion on Gender Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) with Representatives from Global Affairs Canada, Department of National Defence, Department for Women and Gender Equality (WAGE) and Public Safety Canada

- Briefings on their respective experience and expertise in community outreach and GBA+.

- Discussions on: gender, terrorism and counter-terrorism; the intersection of GBA+ with DND’s defence policy ‘Strong, Secure and Engaged’ (SSE); and on the on-the-ground impacts of using a GBA+ lens.

- Discussed the use of GBA+ within the national security and intelligence landscape, including the role it can play in assessing the potential bias of logic employed in artificial intelligence and algorithms.

Theme/Topic:

Discussion with the Assistant Secretary to the Cabinet, Security and Intelligence

- The role of the National Security and Intelligence Advisor (NSIA) within the national security and intelligence community.

- Identifying the intended audiences of past reports produced by review bodies and discussed how the NS-TAG may choose to aim at a particular audience for its own reports moving forward.

Theme/Topic:

Discussion with the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians (NSICOP) Secretariat

- Suggested that in planning for their first report, the NS-TAG should base their priorities around what Canadians would want to know more about and what has not already been covered by other committees or reports.

Meeting 3 – February 2-3, 2020, Ottawa

Theme/Topic:

Discussion with the Information Commissioner and the Privacy Commissioner

- Privacy in the digital age and public access to government information.

- Declassification programs.

- Government access to private citizens’ information for national security reasons (e.g. through social media).

Theme/Topic:

Discussion with the Assistant Chief of Defence Intelligence of the Department of National Defence

- Discussion on future initiatives to enhance transparency and communications at the Department of National Defence, including employee training.

Theme/Topic:

Discussion with Civil Society Representatives

- Allegations of misconduct within the national security agencies.

- Importance of enhancing public understanding of NS agencies through accountability and transparency, engaging diverse communities regularly, and addressing issues with workplace culture within the government.

- Transparency as it relates to judicial decisions, ministerial directions, and orders in council.

Theme/Topic:

Discussion with a Panel of Journalists

- Challenges in accessing historically classified information through the Access to Information Act.

- The lack of information flow from the government following national security incidents can negatively impact marginalized groups and communities. Inadequate communication surrounding these incidents also creates space for harmful entities to undermine democratic values and institutions.

- Recommendations to enhance the relationship between the government and the media. For example: conducting interviews in-person or over the phone; providing valuable and timely information through press conferences and technical briefings; and proactively sharing information on national security events with the media and the Canadian public.

Informal Meeting – May 20, 2020, Virtual

Theme/Topic:

Internal Discussion

- Informal NS-TAG Discussion on forward planning for future NS-TAG meetings in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Meeting 4.1 – June 10, 2020, Virtual

Theme/Topic:

Discussion with Guest Speakers: Privacy Protection, Artificial Intelligence, the Digital World and Cybersecurity: Are Canadians’ Information Expectations and Needs Met?

- Addressing the deficit of public trust in Canada’s national security institutions through transparency and accountability.

- There is a lack of evaluation standards that can be consistently and rigorously applied and assessed by national security review bodies.

- National security institutions should provide more information on the interpretation of legal authorities.

- Better communication and education to bolster public discourse and Parliamentary debates on the following topics: data collection, use and storage; clarity on how laws are being interpreted; enhanced publication process from federal national security departments/agencies.

- Enhanced public debate and inclusive outreach events to enhance the Government’s ability to connect with the public on issues.

- Need for the Government to provide clearer guidance and better partnership opportunities to the private sector in the field of artificial intelligence.

Meeting 4.2 – July 10, 2020, Virtual

Theme/Topic:

Discussion with Guests: National Security and Human Rights: How do Canadians’ individual Rights Factor Into Related Transparency Initiatives?

- The need for accountability by design where we have the level of transparency required for accountability.

- Suggestions on potential concrete steps to bridge the gap and build trust between national security departments and agencies and the communities that feel targeted by their work.

- Feelings of alienation by the public due to the use of processes of legislated listings, bifurcated legal proceedings, ex-parte processes and special advocates in NS.

- People are reluctant to share information when they are unware of what will be done with that information.

- Canadians need access to basic tools and information to manage their interactions with national security institutions.

- Important to address reports of discrimination and harassment within the national security institutions.

- Need to re-examine ways to reach and communicate with Canadians and making sure to include relevant actors who may not have the opportunity to take part in closed-door discussions.

Meeting 4.3 – July 22, 2020, Virtual

Theme/Topic:

Role of the CBSA and the RCMP in National Security and Intelligence.

- Discussions on the role, mandate and operational environment in CBSA and RCMP; how their respective departments fit into the broader national security and intelligence community; and how both organizations engage and communicate with Canadians.

- Discussions on transparency and accountability initiatives, RCMP’s federal and provincial policing role, diversity and inclusion, and the implications of a rapidly evolving digital world on CBSA and RCMP activities.

Theme/Topic:

The Role of the Toronto Police Services Board (TPSB) in National Security Oversight and Review and the Municipal Level.

- Discussion on TPSB’s role and responsibilities.

- Discussed examples of intergovernmental cooperation between different orders of government.

- Outlined best practices and the city’s methods in successfully engaging with the public.

- Key transparency practices, notably with respect to making relevant data available to the public.

Informal Meeting – September 9, 2020, Virtual

Theme/Topic:

Internal Discussion

- NS-TAG’s internal work on drafting the first annual report and address outstanding questions.

- The members agreed to continue developing the report off-line.

- Forward planning on the groups’ second year activities including meeting themes, and report(s).

Annex 5.1: International Jurisdictional Scan of Transparency in National Security

Important: This Annex and the information contained herein was last verified on October 20, 2020, and is subject to change. As part of this report, it will not be updated in the future.

The table below provides an overview of the national security and intelligence (NS&I) transparency policies and institutional features across seven countries. As the NS-TAG’s mandate is to provide advice to the Deputy Minister of Public Safety Canada on enhancing transparency policies in NS&I, this chart provides comparative perspectives to facilitate a critical examination of Canada’s context.

For the purposes of this chart, “Transparency” refers to policies and programs of national security and intelligence agencies that proactively and/or reactively disclose information to its citizens on its activities, policies, programs, and research. All the information provided below are based on publicly available information. Each country is examined across seven aspects:

- Current National Security and Intelligence Transparency Initiatives

- National Security and Intelligence Oversight and Review Bodies

- Freedom of Information Legislation

- Declassification System & Policy

- Available Data in publicly available reports and their corresponding websites

- Policy research institutes (or Think Tanks) in the national security and intelligence area

- Civil society and advocacy groups

For additional reading: A detailed analysis of the relationship between individual Five Eyes countries and their corresponding NS&I oversight bodies can be found in the Library of Parliament.

Important notes to the following table:

- Please note that these are not a comprehensive list of all possible transparency initiatives in the countries being compared.

- Please note that these are not a comprehensive list of all the available data and information on each country’s NS&I website.

- This is not an exhaustive list of all the think tanks in each country. It attempts to list some of the more prominent think tanks that conducts research in national security, defence, intelligence, cybersecurity, and privacy. Annual reports of top think tank index reports can be found here: https://repository.upenn.edu/think_tanks/

- This is not an exhaustive list of all NS&I advocacy groups.

Country |

Current NS&I Transparency Initiatives 1 |

Oversight & review Bodies |

Freedom of Information Legislation |

Declassification System & Policy |

Available Data In Public Reports & Websites2 |

NS & Policy Research Institutes3 |

NS&I NS&I Advocacy Groups4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Canada |

Public Safety Canada Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) Department of National Defence (DND) The Canadian Centre for Cyber Security The Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC) |

National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA) National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians (NSICOP) - Reviews the framework of Canada’s national security and intelligence community, as well as departments that were not previously subject to external review. The Office of the Intelligence Commissioner (no published reports) – the office conducts quasi-judicial review of the Minister’s decisions in issuing ministerial authorizations and determinations for the Communications Security Establishment (CSE) and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS). |

Access to Information Act (1983) In 1983, the Act established the Office of the Information Commissioner The Act outlines exemptions to withhold or deny access to information, including defence and security of Canada and any state allied or associated with Canada. |

Declassification System Treasury Board Directive on Security Management (2019) |

Office of the Information Commissioner NSICOP Annual Report (Redacted) 2018 CSIS Public Report Other reports to consider (may not contain specific data): |

Federal government NS&I Research Institutes NS&I-Specific: Policy Research Institutes with designated NS-related area of focus: Other notable Policy Research Institutes with short-term NS projects: |

Nation-wide groups: Regional-level groups: |

United States |

Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) Homeland Security |

ODNI United States Congress U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs |

Freedom of Information Act (1966) No official Information Commissioner but the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has acted for data security and privacy violations. FOIA includes 9 exemptions, including withholding and denying requests to protect national security. The CIA takes exemptions under the FOIA to protect sources and methods and national security information. Biometric Legislation (State-level): |

Declassification System – EO 13526 (2009) establishes the mechanisms for most declassification. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) ODNI - IC on the Record (ICOTR) NSA Declassification & Transparency |

Statistical Transparency Report Regarding National Security Authorities National Intelligence Strategy ICOTR Transparency Tracker Annual Report on Security Clearance Determination |

Federal government sponsored NS&I Research Institutes: NS&I-Specific: Policy Research Institutes with designated NS-related area of focus: |

Nation-wide groups: Regional-level groups: |

United Kingdom |

Investigatory Powers Act, 2016

|

The Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament (ISC) – the committee of Parliament with statutory responsibility for oversight of the UK IC. Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation – informs the public and political debate on anti-terrorism law Investigatory Powers Commissioner's Office (IPCO) - provides independent oversight and authorization of the use of investigatory powers by intelligence agencies, police forces, and other public authorities Investigatory Powers Tribunal – A judicial forum that investigates complaints about the conduct of UK Intelligence Community, MI5, SIS and GCHQ. Biometrics Commissioner – established by the 2012 Protection of Freedoms Act, the Commissioner is an independent advisor to the government. It reviews the retention and use of biometric data by the police. |

Freedom of Information Act (2000) Information Commissioner’s Office started as a Data Protection Registrar in 1984. The ICO was given an added responsibility of the FOI in 2001 and changed its name to Information Commissioner’s Office. UK’s FOI includes 23 exemptions and is divided into 2 types: Absolute and Non-Absolute. Security matters are classified as one of the absolute exemptions. Thus, all security agencies (ex. MI5, MI6, GCHQ) are exempt from disclosure requests. Data Protection Act (2018) – based on the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation; supersedes the 1998 Data Protection Act. |

Declassification System National Cyber Security Centre's (NCSC) – Indicator of Compromise (IoC) machine. |

ISC Annual Reports NCSC Investigatory Powers Tribunal |

Federal government NS&I Research Institutes: NS&I-Specific: Policy Research Institutes with designated NS-related area of focus: General Policy Research Institutes with short-term NS projects: |

Nation-wide groups: |

Australia |

Office of National Intelligence (ONI) Office of National Assessments (ONA) |

Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security (IGIS) – an independent statutory office that ensures the legality and propriety of the Australian Intelligence Community’s actions, investigate complaints and conduct reviews into AIC agencies and other Commonwealth departments involved in national security. Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security – conducts inquiries into matters referred to it by the Senate, the House of Representatives or a Minister of the Commonwealth Government. |

Freedom of Information Act (1982) at the federal level of government. FOI was amended in 2010, establishing the Office of the Information Commissioner. FOI outlines ten exemptions, including documents that affects national security, defence, or international relations. |

Declassification System |

IGIS Annual Reports |

Federal government NS&I Research Institutes: NS&I-Specific: Other notable Policy Research Institutes with NS projects: |

Nation-wide groups: |

New Zealand |

Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB) Australia-New Zealand Counter-Terrorism Committee (refer to the Australia section for more info) |

Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security (IGIS) – provides independent oversight of the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service and the Government Communications Security Bureau. IGIS can investigate, conduct inquiries, and review intelligence agencies. |

The Official Information Act (1982) The Office of the Ombudsman established in 1962, is an equivalent body to Canada’s Office of the Information Commissioner. The country’s Ombudsman investigates complaints against government agencies. The OIA outlines conditions to deny access to information, including the national security and defence of N.Z. (OIA, Part 1, Section 6). |

Declassification Policy |

IGIS Publication MFAT Declassification Program |

NS&I-Specific: |

Nation-wide groups: |

Germany |

Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community publishes various reports on its website German Domestic Intelligence Service (BfV) German Parliamentary Committee investigation of the NSA spying scandal |

The Parliamentary Control Panel (the Panel) – The Parliamentary Scrutiny of Federal Intelligence Activities Act allows the Panel to investigate the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV), Military Counterintelligence Service (MAD), Federal Intelligence Service (BND). The Panel investigates the federal government’s disclosure obligation since the federal government is required to volunteer following information: The Panel can compel the intelligence services to hand over evidence. However, the intelligence agencies can refuse to disclose information to the Panel under certain circumstances (ex. protection of sources, infringement of an individual’s right). The Panel also regularly reports to the federal parliament G10 Commission of the Parliament |

Freedom of Information Act (2006) Federal Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (BfDI) is the agency mandated to supervise data privacy. The 2006 FOI act added an Ombudsman function to the agency. In 2016, BfDI became an independent agency. Germany’s foreign intelligence agencies and certain activities within the federal police services are exempt from disclosure of information requests. |

Declassification Policy |

Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community The Parliamentary Control Panel German Domestic Intelligence Service Federal Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (BfDI) |

Federal government NS&I Research Institutes: NS&I-Specific: Notable Policy Research Institutes with NS area of focus: |

Nation-wide groups: |

Netherlands |

General Intelligence and Security Service (GISS) Intelligence and Security Services Review Committee (CTIVD) The Counter-Terrorism Infobox (CT Infobox) |

Intelligence and Security Services Review Committee (CTIVD) Parliamentary Oversight Committees (they do not carry out investigations, and do not produce reports) |

Government Information (Public Access) Act or Wet Openbaarheid van Bestuur (Wob) (1980) The Dutch Public Access Act makes the distinction between passive and proactive information disclosure. However, unlike passive disclosure, proactive disclosure is not enforceable. The Public Access Act has 11 exemptions. Authorities in the parliament, the judiciary, and some executive authorities like the Intelligence and Security Services Review Committee (CTIVD) are not expected to disclose information upon requests. Likewise, information that is processed by, or, in support of the intelligence services are exempted. No official Information Commissioner but does have a Dutch Data Protection Authority (similar to the Privacy Commissioner). Objections with Public Access request decisions by a government body are made directly to the government body, including the higher appeals process. |

Declassification Policy |

CTVID Publications GISS Publication National Coordinator for Counterterrorism and Security (NCTV) |

Federal government NS&I Research Institutes: NS&I-Specific: Notable Policy Research Institutes with NS area of focus: |

Nation-wide groups: |

Annex 5.2: Transparency Policies in National Security and Intelligence in Selected Governmental Organizations at the International Level

Important: This Annex and the information contained herein was last verified on October 20, 2020, and is subject to change. As part of this report, it will not be updated in the future.

The tables below provides information on the national security and intelligence (NS&I) transparency policies and initiatives in four governmental organizations at the international level. These are organizations that have NS&I implications for Canada, either directly or indirectly.

All the information provided below is based on publicly available information and is not a comprehensive list of all the available data and information.

European Union

General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

- GDPR was ratified by the European Parliament in 2016 and came into force in on May 25, 2018. It has had and continues to have significant impact in regulating the global data market.

- The framework builds on the 1998 Data Protection Directive. It aims to upgrade and harmonize regulations and organizational practices for protecting personal information of individuals. GDPR also provide guidance on how businesses should handle information of their clients. Each European country within the EU can tailor GDPR according to their contextual needs.

- Personal data can include information on an individual’s name, location, IP addresses and cookie identifiers, and online username. There are also special categories personal data that are given higher level protections. These special categories can include information such as genetic and biometric data, health information, racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious beliefs, and sexual orientation.

- GDPR includes sections for Principles (Articles 5-11) as well as Rights for data subjects (Articles 12-23).

- “Lawfulness, Fairness and Transparency”, “Integrity and confidentiality”, and “Accountability” are among the core principles of GDPR.

- Rights for individuals include: the right to be informed, the right of access, the right to data portability, and rights around automated decision making and profiling.

- While GDPR does not explicitly define transparency, Articles 12 to 14 lays out specific requirements for data controllers and processors:

- Article 12: Transparent information, communication and modalities for the exercise of the rights of the data subject (provides general rules on transparency).

- Article 13: Information to be provided where personal data are collected from the data subject (concise, transparent, intelligible communications with data subjects concerning their rights).

- Article 14: Information to be provided where personal data have not been obtained from the data subject (concise, transparent, intelligible communications with data subject in cases of data breaches).

- Restrictions: The degree of obligation to provide information to data subjects as outlined in Articles 13 and 14 may be lowered depending on each country’s national measures according to their respective fundamental rights and freedoms. Article 23 lists restrictions to GDPR, including safeguarding of national security, defence, and public safety.

- Implications of GDPR on Canada:

- GDPR applies to all organizations storing or processing the person data of EU citizens, regardless of their privacy maturity level. GDPR requires those businesses and organizations to take steps to comply with GDPR such as, the creation of data protection officers, the implementation of privacy-by-design principles to new processes and technologies, and maintenance of data processing records.

- There are heavy financial and reputational penalties for non-compliance or inaction.

- Automated decision making and profiling:

- Article 22 includes provisions around AI-based automated decision-making systems and profiling. It aims to ensure that artificial intelligence (AI) technology cannot be used as a sole decision maker in cases that impacts individuals’ rights and freedoms.

- Biometrics:

- GDPR categorizes biometrics in two ways: physical and behavioral characteristics.

- As mentioned above, biometric data used to identify an individual is classified as “sensitive data” under GDPR. As such, use of biometric data of EU citizens are restricted and subject to the regulations.

- Organizations that collect and use biometric data will need to undertake privacy impact assessments (PIA).

- On facial recognition the European Commission’s executive vice president for digital affairs have stated that facial recognition breaches GDPR because the technology fails to meet the requirement for user consent.

EU-Canada Passenger Name Records (PNR) Agreement

- The Passenger Name Records is a data sharing agreement between EU and Canada for the purposes of “the prevention, detection, investigation or prosecution of terrorism offences or serious transnational crimes.”

- PNR contain data on the flight details that are stored in airliners’ database, such as the passenger’s itinerary, contact information, forms of payment, and guests.

- The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has rejected the draft Passenger Name Record (PNR) Agreement between Canada. The Opinion of CJEU stated that the EU-Canada PNR agreement is not compatible with the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights in its current form. Charter Rights are not absolute. PNR agreement can be established allowing for sharing and retention of data to safeguard national security and public safety despite serious infringement on privacy and personal data protection. However, such infringement should be guided by clear and precise rules governing its scope and application (Section VI, A.39), strictly necessary (Section VI, B.41), and proportionate (Section VII, C.54).

- Currently, EU has PNR agreements with the United States (retention of PNR data for up to 15 years) and Australia (retention of PNR data for a period of up to 5.5 years). EU has also adopted its own internal PNR framework that allows for a retention of PNR data up to 5 years.

Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) on Security and Defence

- As part of the EU’s security and defence policy, the EU Global Strategy for Foreign and Security Policy (EUGS) formed the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO). It is a treaty-based framework between 25 EU member states. It aims to promote closer cooperation and increased investment by the member states in the face of security threats and strengthening in developing security and defence capabilities.

- Specifically, PESCO focuses on three areas:

- Deepening collaboration: collaboration between participating member states are formal and binding, and no longer ad hoc;

- Majority of PESCO projects are linked to operational needs;

- PESCO can be used in concert with other tools to identify gaps and opportunities for new initiatives. It aims to avoid duplication and streamline resources.

- Participating member states: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden.

Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD)

- In 2016, the EU Global Strategy for Foreign and Security Policy (EUGS) created the Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD0 to foster capability development through analyses and assessment of the EU’s defence and security plans and capability landscape.

- Its objective is “to develop, on a voluntary basis, a more structured way to deliver identified capabilities based on greater transparency, political visibility and commitment from Member States.” It aims to enhance cooperation between member states and ensure the optimal use of defence spending in conjunction with PESCO.

Resources:

- General Data Protection Regulation

- PNR: Opinion 1/15 Of The Court

- PESCO Fact Sheet

- Permanent Structured Cooperation on Defence PESCO

- Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD)

Five-Eyes Countries

- A multilateral intelligence alliance between five Anglophone countries: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States. It is an agreement between the five countries to share by default signals intelligence that they gather.

- There is very little information on the legal framework underlying the intelligence sharing and how intelligence sharing is conducted. The most recent publicly available information dates back to 1955.

- On July 2017, Privacy International and Media Freedom & Information Access Clinic (Yale Law School) filed a lawsuit against the National Security Agency, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the State Department, and the National Archives and Records Administration. The lawsuit sought information and access to records of the Five Eyes activities. The NSA and the State Department have disclosed limited information as a response.

- Disclosures:

- 1959-61 Appendices to the United Kingdom-United States Communication Intelligence (UKUSA) Agreement

- 1961 General Security Agreement between the Government of the United States and the Government of the United Kingdom (General Security Agreement)

- 1998 Agreement to Extend the 1966 Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the United States of America relating to the Establishment of a Joint Defence Facility at Pine Gap (Pine Gap Agreement)

Note: Information provided above is based on secondary sources of information.

Five Eyes Intelligence Oversight and Review Council (FIORC)

- The scope and purpose of FIORC, meetings, operational guidelines, and the administrative elements are set out in the Charter.

- Council of FIORC is composed of non-political intelligence, oversight, review, and security organizations of the Five Eyes countries:

- The Office of the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security of Australia

- The National Security and Intelligence Review Agency of Canada

- The Office of the Intelligence Commissioner of Canada

- The Commissioner of Intelligence Warrants & the Office of the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security of New Zealand

- The Investigatory Powers Commissioner's Office of the United Kingdom

- The Office of the Inspector General of the Intelligence Community of the United States

- The Council meets in person to discuss mutual interests and concerns, compare best practices in review and oversight methodology, explore new opportunities for cooperation on reviews and information sharing, and encourage transparency to enhance public trust.

- Executive summaries of the annual meetings are publicly available.

Resources:

- Lawfareblog.com article: “Newly Disclosed Documents on the Five Eyes Alliance and What They Tell Us about Intelligence-Sharing Agreements”

- Justsecurity.org article: “The “Backdoor Search Loophole” Isn’t Our Only Problem: The Dangers of Global Information Sharing”

- ODNI - Five Eyes Intelligence Oversight and Review Council (FIORC)

- The Charter of FIORC (PDF)

Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD)

OECD Principles on Artificial Intelligence (AI)

- In 2018, OECD’s Committee on Digital Economy Policy created an Expert Group on AI (AIGO) to provide guidance on scoping principles for the integration of AI into the society and economy. The groups included experts from OECD members. Canada had one representative from Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR) on AIGO.

- The Principles serve as international standards on AI that “aim to ensure AI systems are designed to be robust, safe, fair and trustworthy.” It was adopted on May 21, 2019. 42 countries adopted the Principles, including Canada.

- The European Commission have provided its support for the Principles.

- Implications in Canada

- Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy: In 2017, the Government of Canada budgeted $125 million for Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy and appointed a non-profit research institute CIFAR to develop and lead a national AI strategy. CIFAR works with three of Canada’s national AI Institutes (Vector Institute, Mila, Amii), universities, hospitals, and other organizations. CIFAR’s AI & Society Program is a key pillar of the Pan-Canadian AI Strategy. It aims to connect experts across various sectors (academia, industry, law, ethics, healthcare, and government, etc.) to conduct in-depth discussions on timely issues and challenges.

- Canada-France International Panel on AI: On July 2018, the Canadian and the French government announced that they would work to create an International Panel on AI. The objective is to create a global point of reference for sharing research on AI issues and best practices. The aim is to create “promote a vision of human-centric artificial intelligence.”

Resources:

- OECD Principles on AI

- Artificial Intelligence in Society

- Recommendation of the Council on Artificial Intelligence

- CIFAR Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy

- CIFAR Report on National and Regional AI Strategies

- Mandate for the International Panel on Artificial Intelligence

- News Release

North Atlantic Treaty Organization

North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

- NATO is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 countries. Canada was a founding member of NATO since 1949. Canada currently has a joint delegation to NATO consisting of political, military, and defence-support sections.

- Financial Transparency

- NATO is funded by its member countries, and thus is accountable to its member governments.

- NATO publishes annual civilian budget totals (administrative costs for NATO Headquarters) and military budget totals (costs of the integrated Command Structure), NATO Security Investment Programme budget (military capabilities), and annual compendium of financial, personnel and economic data for all member countries.

Unified Vision

- Each year, NATO undertakes a major trial managed by Allied Command Transformation and NATO Headquarters in the context of NATO's Joint Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (JISR). JISR provides key decision-makers and operators with an enhanced situational awareness of what is happening on the ground to facilitate a timely and well-informed decision. The allies share the burden of collecting, analyzing, and sharing information. JISR brings together surveillance and reconnaissance data gathered through various projects.

- For example, Unified Vision 2016 was a test to improve the Alliance’s ability to share and process complex intelligence. According to the organization, the outcomes of the trial has been stated to improve how the Alliance responds to multinational operations, hybrid warfare, and leverage the new Alliance Ground Surveillance capability.

NATO Building Integrity (BI) Policy

- NATO Building Integrity Policy was endorsed in 2016 NATO Summit.

- The Building Integrity Policy and Action Plan works with member countries to promote good governance and implement principles of integrity, transparency, and accountability in NATO policy. BI policy aims to prevent insecurity, extremism, and terrorism faced by partners and other nations through good governance practices.

- NATO BI Policy contributes to the three core NATO tasks: collective defence, crisis management and cooperative security.

- NATO BI works with United Nations, World Bank and European Union to promote good governance practices and is supported by experts across sectors.

Resources:

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

- Financial Transparency and Accountability

- Canada and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization

- Unified Vision 2016

- Unified Vision 2018

- NATO Building Integrity Policy

- Building Integrity

Footnotes

- 1

“The Government of Canada Response to the Commission of Inquiry into the Investigation of the Bombing of Air India Flight 182.” Public Safety Canada, 21 Dec. 2018, www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/rspns-cmmssn/index-en.aspx.

- 2

Bruce, James B., et al. “Secrecy in U.S. National Security: Why a Paradigm Shift Is Needed.” RAND Corporation, 1 Nov. 2018, www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE305.html.

- 3

“Canada.” Open Government Partnership, 2020, www.opengovpartnership.org/members/canada/.

- 4

Johal, Sunil, et al. “Reprogramming Government for the Digital Era.” Mowat Centre, Munk School of Public Policy & Governance, 11 Sept. 2014, https://munkschool.utoronto.ca/mowatcentre/wp-content/uploads/publications/100_reprogramming_government_for_the_digital_era.pdf. Page 12.

- 5

Federal Court, 16 July 2020, www.fct-cf.gc.ca/Content/assets/pdf/base/2020-07-16-CONF-1-20-CSIS-duty-of-candour.pdf.

- 6

Federal Court, 22 November 2013, https://decisions.fct-cf.gc.ca/fc-cf/decisions/en/66439/1/document.do.

- 7

Federal Court, 4 October 2016, https://decisions.fct-cf.gc.ca/fc-cf/decisions/en/212832/1/document.do.

- 8

“SIRC Annual Report 2017–2018.” Security Intelligence Review Committee, 20 June 2018, www.sirc.gc.ca/anrran/2017-2018/index-eng.html#section_3. Section 3.

- 9

Federal Court, 31 October 2018, https://decisions.fct-cf.gc.ca/fc-cf/decisions/en/349913/1/document.do.

- 10

“National Security Consultations: What We Learned Report.” Public Safety Canada, 21 Dec. 2018, www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/2017-nsc-wwlr/index-en.aspx.

- 11

Ibid.

- 12