Crime Prevention Programs in Canada: Examining Key Implementation Elements for Indigenous Populations

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Methodology

- Description of Projects and Services Delivered

- Detailed Results

- Discussion

- Conclusions and Recommendations

- References

- Footnotes

by Hannah Cortés-Kaplan and Laura Dunbar

RESEARCH REPORT: 2021-R001

Abstract

This research study sought to examine the unique implementation issues for crime prevention programs aiming to serve Indigenous populations. This was completed through the analysis of implementation data from 49 crime prevention projects with completed evaluations, funded under the National Crime Prevention Strategy. The purpose was to examine the information that currently exists related to the implementation process, to provide an in-depth understanding of the associated challenges and strategies, and to identify possible recommendations for moving forward. An exploratory research design was employed, whereby data obtained from evaluation reports and related documents, were analyzed using Microsoft® Excel and QSR International NVivo 10. Results demonstrated that projects experienced implementation challenges in the following areas: program accessibility; funding requirements; management and administrative issues; and time management and planning deficiencies. Although few strategies were identified overall, adding a cultural element or making cultural adaptations were acknowledged as important components in addressing challenges. Findings from this research study identified the importance of program readiness and planning, resource limitations, culturally relevant adaptations, and formative evaluation in the implementation process. Knowledge of the latter may in turn help to assist crime prevention practitioners and policy makers in their understanding of implementation issues and strategies for improving projects aimed at serving Indigenous populations moving forward.

Author’s Note

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Public Safety Canada. Correspondence concerning this report should be addressed to:

Research Division

Public Safety Canada

340 Laurier Avenue West

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0P8

Email: PS.CPBResearch-RechercheSPC.SP@ps-sp.gc.ca

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Janet Currie and Tim Roberts [Focus Consultants] for their work on the development of the original database of crime prevention programs, and for their preliminary analyses on a number of the projects included in this research report.

Introduction

The Government of Canada is committed to reducing crime and enhancing the safety of communities through effective prevention, policing, and corrections. With respect to prevention, Public Safety Canada is responsible for implementing the National Crime Prevention Strategy (NCPS). The Strategy aims to reduce crime by targeting at-risk groups in the population by funding evidence-based prevention programs and knowledge dissemination projects. Focusing on effective ways to prevent and reduce crime, Public Safety Canada continues to gather and synthesize national evidence on what works to help guide policy and program decisions. This information contributes to the body of empirical knowledge in the crime prevention domain.

While crime prevention initiatives in Canada are increasingly being evaluated in order to measure their impact on populations of interest, examination of the elements of implementation that contribute to program effectiveness has not progressed at the same rate. Public Safety Canada seeks not only to gather national evidence on what works, but also evidence on how crime prevention programs are implemented and in which context(s) they are most effective.

Presently, the literature confirms that some aspects of implementation are generalizable across various sectors, particularly with regard to the stages of implementation and the key components (Fixsen, Naoom, Blasé, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005). However, certain conditions in the implementation of crime prevention programs suggest that there may be certain elements, even particular challenges and strategies that are specific to this sector (Savignac & Dunbar, 2014). Further, there are a number of factors that may be more or less likely to increase the probability of success with implementation of programs involving different populations.

Of particular interest are any specific and unique implementation issues that should be considered as part of realizing any crime prevention initiative aiming to serve Indigenous populations. In Canada, the need for culturally relevant programming for Indigenous peoples is well documented. As a result of colonialism and intergenerational trauma, their rates of violence, victimization, substance abuse, mental health issues, and other socio-economic vulnerabilities are higher than among their non-Indigenous counterparts (Boyce, 2016). The rates of crime and victimization are indicative of the present problems of overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in the criminal justice system. Indigenous communities and populations present distinct differences for program responsiveness and successful interventions. In the Government of Canada’s efforts to improve relationships with Indigenous communities and populations, this research study will contribute to efforts to improve the implementation of programs aimed at serving these groups.

To this end, the current research study sought to examine implementation information from a subset of NCPS funded crime prevention projects with a completed evaluation. The major findings related to key implementation elements can assist crime prevention practitioners and policy makers in their understanding of common challenges associated with implementing programs for Indigenous populations, and practical information about how they may be addressed and mitigated. They can also help to identify gaps in the information being collected about key implementation elements that can be filled through future data collection and analysis in order to provide additional knowledge about challenges and ways to address them. This research report provides an overview of the pertinent research literature on implementation, presents the methodology used to carry out this particular research study, briefly describes the NCPS funded projects and the services delivered, presents the key findings, and provides some conclusions and recommendations for moving forward.

Literature Review

This literature review section seeks to provide background information on implementation science, implementation in the context of crime prevention initiatives, including strategies and challenges, and considerations for Indigenous populations. The latter includes examining the role of culture, location, and historical experiences, as well as other factors that can affect implementation.

Implementation Science

Implementation science is defined as the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic adoption of research results and other evidence-based practices into current practice with a view to improve the quality (effectiveness, reliability, security, relevance, equity, efficiency) of services for the public (adapted from Eccles et al., 2009). Implementation science is multi-sectoral and applies to programs in a variety of areas including health and wellness, education, and crime prevention (Bauer, Damschroder, Hagedorn, Smith, & Kilbourne, 2015; Bauer & Kirchner, 2019; Bhattacharyya & Reeves, 2009; Eccles et al., 2009; Proctor et al., 2009). Implementation science examines the gaps between research and practice as well as individual, organizational, and community influences surrounding the implementation process (Savignac & Dunbar, 2014). This allows for greater definition of implementation strategies to introduce or change evidence-based interventions. For example, implementation science is concerned with the development of knowledge, with the goal to incite change by helping different practitioners (Proctor & Rosen, 2008). In examining a particular program, this field of study aims to promote the use of successful evidence-based interventions in routine practice.

Implementation science considers the wide-range of environments and settings within which implementation transpires. It occurs in varying contexts, which include “the social, cultural, economic, political, legal, and physical environment, as well as the institutional setting, comprising various stakeholders and their interactions, and the demographic and epidemiological conditions” (Peters, Adam, Alonge, Agyepong, & Tran, 2013, p. 1). In addition, implementation research includes multiple targets of investigation. For example, research examining the implementation of a particular project may involve collecting data across a variety of levels, such as observation data (participants, providers, facility, organization) and broader environmental factors such as community, policy environment, and economic situation (Bauer & Kirchner, 2019; Peters et al., 2013). It is worth noting that these parts of implementation are interconnected and can affect one another, therefore, they should be evaluated both together and separately.

The implementation process can be described using a multi-level model. In their examination of mental health services, Proctor and colleagues (2009) analyzed implementation using a top-, middle-, and bottom-level approach. The top-level represents the policy context, which follows the understanding that implementation is included in a policy, typically relating to changes at the request of the government. For example, a policy to ensure that effective interventions are implemented in diverse settings and populations. Second, the middle-level represents the organizations and groups. For example, the organizational culture may influence whether an organization has the ability and inclination to implement certain interventions. Finally, the bottom-level describes the crucial role that individual behaviour plays in implementation.

Furthermore, implementation has several stages, for example, exploration and adoption, program planning, initial implementation, full operation, innovation, and sustainabilityFootnote1. Throughout the entire process it is necessary that all stakeholders are aware of the role they play, and the impact that political and financial changes can have on implementation. Program management, staff, and the community “must be aware of the shifting ecology of influence factors and adjust without losing the functional components of the evidence-based program” (Fixsen et al., 2005, p. 17). Evidence-based programs allow for the implementation of new programs to use models and examine the successes and challenges. They represent a way to transform the conceptual goal-oriented needs of program funders and organization directors into the specific methods necessary for effective treatment, management, and quality control (Fixsen et al., 2005).

Implementation Science and Crime Prevention Programs

Implementation science as applied to criminal justice settings is an emerging field, and offers the opportunity to provide frameworks, models, and insights that will assist both researchers and practitioners in their quest to apply evidence-based practices in the field (Hanson, Self-Brown, Rostad, & Jackson, 2016). The implementation of a crime prevention program is multifaceted, involving careful planning, taking note of staffing requirements, training, possible challenges and strategies, and how programs may be adapted while maintaining awareness of differences in settings and target populations. This involves a clear understanding of the multitude of elements that interconnect, and their impact on implementation. There are different crime-related concerns across communities and these demonstrate differences in social and cultural contexts. As well, the nature and meaning of crime and violence may be different in Indigenous communities. As a result, “attitudes towards crime and prevention may be affected by changes in city life, crime rates and trends, the media, and that crime is addressed in the political arena” (Podolefsky, 1985, p. 36).

Before attempting to introduce a new program or practice, organizational readiness should be assessed, considering current strengths and gaps, and identifying areas for needed capacity building (Meyers, Durlak, & Wandersman, 2012). In selecting crime prevention programs for implementation, the “analysis of organizational resources and capacities is too often a missing piece” (Savignac & Dunbar, 2015, p. 14). Organizational readiness for implementation examines the extent to which an organization is both willing and able to implement and sustain a selected intervention. When organizational readiness is high, effective and sustained implementation of a new program is more likely; when readiness is low, change and implementation efforts are more likely to fail (Dymnicki, Wandersman, Osher, Grigorescu, & Huang, 2014). A growing body of work points to three core components of readiness for implementation: (1) motivation, which refers to the willingness or desire of individuals in an organization to change and adopt an intervention; (2) general capacity, which refers to aspects of an organization’s healthy functioning (e.g., effective leadership, appropriate staff, and clear expectations and procedures); and (3) intervention-specific capacity, which refers to the human, technical, and physical conditions needed to implement a particular program or practice effectively (Dymnicki et al., 2014; Scaccia et al., 2015). If any one of these components is missing, then the organization is unlikely to be ready. As an organization becomes stronger in each area, its level of readiness for successful implementation grows. Similarly, Savignac and Dunbar (2015) note four organizational factors to facilitate the implementation of high-quality crime prevention programs, these are: operational capacity; financial capacity; previous experience; and sound and effective partnerships and networksFootnote2.

Sustainability is defined as “the extent to which an evidence-based intervention can deliver its intended benefits over an extended period of time after external support… is terminated” (Rabin & Brownson, 2017, p. 26), whereas sustainment relates to creating and supporting the structures and processes that will allow an implemented intervention to be maintained in an organization (Aarons et al., 2016). Therefore, the sustainability of initiatives requires thoughtful planning and attention throughout the implementation process. The sustainment of interventions presents many complexities and organizations often face different unanticipated challenges pertaining to intervention characteristics, the organizational setting, and the broader policy environment (Damschroder et al., 2009). Other barriers to sustainability include: securing funding; providing services to special populations; strategic planning and prioritizing sustainability planning; achieving local buy-in; creating and maintaining partnerships; and securing local political support (Savignac & Dunbar, 2015). Hailemariam and colleagues (2019) conducted a systematic review to summarize the existing evidence supporting discrete sustainment strategies for evidence-based interventions and identified nine such strategies. Most frequently reported were funding and/or contracting for continued use of the intervention and maintenance of workforce skills through continued training, booster training sessions, supervision, and feedback. Other sustainment strategies included: organizational leader stakeholder prioritizing and supporting continued use; aligning organizational priorities, and/or program needs with the intervention; maintaining staff buy-in; accessing new or existing money to facilitate sustainment; systematic adaptation of the intervention to increase continued fit/compatibility of the latter with the organization; mutual adaptation between the intervention and the organization to improve fit and alignment of the organization’s procedures; and continued monitoring of the intervention’s effectiveness. It is important to note that many of the challenges and successes mentioned above align with health programs, but many similarities can be drawn with crime prevention programs (Savignac & Dunbar, 2015).

In addition to planning, staff and others involved in program delivery can also have a significant impact on the success or failure of program implementation. The main factors related to crime prevention practitioners are the attitudes toward and perceptions of the program; level of confidence; and skills and qualifications (Savignac & Dunbar, 2015). The processes of hiring and training are components that contribute to successful implementation. To understand their contributions, researchers have sought to analyze what requirements are needed for each to understand how it was carried out (Public Safety Canada, 2012). Fixsen and colleagues (2005) found that staff need to have a high degree of understanding of the practices being implemented in the organization, making the selection of staff significant in ensuring that evidence-based practices and programs are carried out. This degree of understanding and knowledge demonstrates how one’s profession and training can influence program implementation. Specific to the area of crime prevention, it is important for staff to have experience working with at-risk individuals and those who have engaged in criminal behaviours, to identify the criminogenic needs, and to have the ability to provide the required support and services. Training provides program staff with the tools and opportunities for skill development related to delivering program activities, as well as community and service development skills (Cunneen, 2001). However, there is limited academic literature examining the impact of staff training on program participants, and there are several factors that are known to impact the delivery of training (Fixsen et al., 2005). For example, as many program activities are delivered in schools, finding the time for teachers to participate in training may be difficult (Fixsen et al., 2005). Other things to consider are the target audience(s) and whether the training will be unique to each position or general for all staff.

Furthermore, staff turnover is a common factor that can directly impact program implementation. This may be due to the working environment, job type (term, contract, full-time, part-time), job autonomy, and work attitudes, among other things. In fact, Aarons Sommerfeld, Hecht, Silovsky, and Chaffin (2009) studied the effect of staff turnover on evidence-based practice implementation and fidelity and how it can influence the quality and outcomes of services. They found that turnover negatively influences staff morale, organizational effectiveness, reduces productivity, increases costs of training for new employees, leads to inconsistent services, and decreases intervention fidelity. Having limited staff and staff turnover can lead to what McKay, Bahar, and Ssewamala (2019) called task shifting, which is a process whereby tasks are moved from one group of specialized or well-trained workers to another group or type of worker with shorter training and fewer qualifications. This largely occurs due to having limited staff capacity or the inability to find qualified staff, although service and program delivery must continue.

Program adaptation is described as the modification of an evidence-based program or intervention to meet the unique needs of a specific situation within a certain population, location, and/or community capacity (Public Safety Canada, 2017b). Importantly, it needs additional resources (personnel, time, and funds), planning, and evaluation to monitor the adaptations and evaluate the outcomes (Savignac & Dunbar, 2015). Moreover, the ability to adapt and make program modifications has been discussed as being significant in the capacity to proceed with implementation. For example, Kirsch, Siehl, and Stockmayer (2017a) found that “program staff need to understand the nature of the transformation and remain conscious of the fact that there are only a few stable conditions in it, and that content, alliance, ownership, commitment, and resources change over time” (p. 32). In fact, program adaptations are required for a number of factors, and staff must be aware of the ever-changing environment and have the ability to sustain the program. Kirsh and colleagues (2017b) noted several challenges that occur during the program implementation. They include: “unexpected political developments; resistance to changes from staff within organizations who are needed to implement reforms; mistrust among actors avoiding cooperation; lacking common understanding and agreement on central elements; capacity and resource constraints; and the institutional environment not providing sufficient flexibility for programs to adapt to changing local circumstances” (p. 328). Program implementation is not exempt from challenges, in order to successfully implement a crime prevention program, the knowledge of such challenges will help the program continue if adaptations are required. Such strategies to adapt implementation are required to overcome obstacles to program implementation. Implementation strategies attempt to overcome such challenges and sustain the program. They enable practitioners to “deal with the contingencies of various service systems or sectors and practice settings, as well as the human capital challenge of staff training and support, and various properties of interventions that make them more/less amenable to implementation” (Proctor et al., 2009, p. 26).

Crime prevention programs must understand and address the unique needs of their diverse target communities and populations. In a study examining implementation of crime prevention programs in Uganda, McKay and colleagues (2019) found that many of the interventions and implementation strategies originally designed for developed regions were applied to developing ones. This means that it is necessary for interventions to make adaptations where possible to better fit each community. Similarly, Podolefsky (1985) explained that recognizing the differences that exist between communities, whether it be in general, or in terms of their crime-related characteristics, allows for dynamic crime prevention programs. This demonstrates the importance of understanding the social and cultural contexts. Specifically, because of diverse factors in high-needs communities, program implementation recognizes the major social problems that exist, such as unemployment, poverty, substance abuse, welfare and food programs, language barriers, etc. (Podolefsky, 1985). In fact, to facilitate implementation in transformative settings, specific expertise and skills are required, whether it be practice, technical, or theoretical (Kirsch et al., 2017b). Additionally, adaptations must reflect both the needs and goal of the program and must be intentional and planned. For example, appropriate adaptations to program activities account for age groups, culture, and context of the population while inappropriate adaptations remove or modify key aspects of the program that may weaken the program’s effectiveness (Public Safety Canada, 2017b).

A major aim of implementation science is to investigate and address major bottlenecks (e.g., social, behavioural, economic, management) that imped effective implementation. This is important since historical and current inequalities like those experienced by First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples in Canada may be addressed by this field of study.

Considerations for Indigenous Populations

While the field of prevention science has generated and amassed substantial evidence for many programs and approaches, Indigenous communities have largely been left out of the participant pools of both efficacy and effectiveness trials (Ivanich, Mousseau, Walls, Whitbeck, & Whitesell, 2018; Jernigan, D’Amico, & Kaholokula, 2020). Thus, less is known about what works in these communities. This drives the need for research to focus on the rate and scope within which existing or promising Indigenous service delivery models or prevention programs are transferred and implemented within and across communities (McCalman et al., 2012). The historical, cultural, geographic, and political diversity that exists in Indigenous communities (Grover, 2010; Jernigan et al., 2020) creates unique implications for crime prevention programs. This implores the need for innovative programming and implementation. The following section focuses largely on work involving Indigenous populations in Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand.

Crime prevention programs for Indigenous peoples must examine the historical context and recognize how colonization, assimilation, and a number of other factors will affect implementation. For example, colonization (including the use of residential schools) has profoundly affected the Indigenous population in Canada and elsewhere, leading to the loss of land, broken families, and the loss of language, culture, and identity (Capobianco & Shaw, 2003; Grover 2010). Linked to the latter, Indigenous peoples face a large number of risk factors, such as child abuse, school failure, unsupportive family environments, substance abuse issues, and relatively few protective factors (Capobianco & Shaw, 2003; Homel, Lincoln, & Herd, 1999). Furthermore, it is in recognizing that Indigenous crime is not solely an Indigenous problem, but rather the product of circumstances created by history, social policies and structures, local conditions, and colonial criminal justice practices (Homel et al., 1999), that successful program implementation will be possible.

The research literature points to the importance of culturally sensitive crime prevention programs that aim to develop strong community partnerships and are respectful of Indigenous rights. This reflects the importance of cultural continuities and how the lack of relationship building and cultural recognition may hinder implementation efforts (Cunneen, 2001; Homel et al., 1999; Jernigan et al., 2020). Cultural resilience is a major protective factor for Indigenous peoples and importance is placed on relationships within their communities. Strategies such as building trust, effectively communicating to all participants, and having an inclusive working relationship will contribute to strengthening these relationships (Grover, 2010). Kinship ties, socialization practices, Indigenous languages, and other religious frameworks are significant in ensuring that these programs are not developed in isolation from their community context (Homel et al., 1999).

Emery (2000) examined how to integrate traditional knowledge in project planning and implementation. The study found that using traditional knowledge promotes active community involvement and sustainability. Incorporating traditional knowledge in project planning encourages the collaboration between various partners to evaluate the applicability of program components to Indigenous peoples. Issues can develop when adopting program components and guidelines that have not previously been applied to an Indigenous population. For instance, local knowledge and clinical judgement are required to interpret the adaptability to Indigenous peoples and communities. As well, there is an obligation to involve those in positions of authority, including Elders, leaders of organizations, parents, and older family members throughout the process (Cunneen, 2001). These individuals have knowledge and insights about how their community works and can provide guidance about the required adaptations. For example, the Restitution Peace Project in Yellowknife included community partners on the steering committee, and through this they were able to promote the program in their own organizations. This helped with the implementation of the program model in other communities and ensured sustainability of the program (Capobianco & Shaw, 2003). Another example is how programming can use cultural knowledge and community collaboration to include cultural activities into programming. For instance, the Kāholo Project in Hawaii used a culturally accepted form of physical activity into their programing called hula. In consulting directly with Indigenous communities who practice hula, they used this as the main intervention component, as it encourages social cohesion, cultural values, and connectedness to the world (Jernigan et al., 2020).

In addition to cultural differences, Indigenous communities and populations are diverse in their settings. There are more than 3,100 self-governing Indigenous communities across Canada, in addition to many other Indigenous communities that are dispersed throughout urban, rural, and small communities. Therefore, evidence-based programs “developed in dominant culture settings do not always translate to Indigenous settings, especially if culturally supported interventions, including indigenous theories and context, are excluded from the research” (Jernigan et al., 2020, p. 76). Unique differences such as scheduling, language, and compensation make for careful planning. For example, scheduling must take into consideration the communities’ seasonal requirements; language translation might be required; and individuals may require compensation for their commitment to the program (Emery, 2000). These considerations, among others, are more likely to be incorporated with community engagement and recognizing the disparities existing across different types of communities. A common approach is to take an evidence-based practice or program with documented effectiveness in other populations and implement it with Indigenous populations. While the science of intervention adaptation is emerging, there remains little guidance on processes for adaptation that strategically leverage both existing scientific evidence and Indigenous prevention strategies.

Using Evaluation to Examine Implementation

Increasingly, crime prevention programs are being evaluated in order to measure their impact on the participant group such as their ability to reduce problematic behaviours or to strengthen protective factors. However, the field continues to be challenged by questions about why a selected program works and under what circumstances (Harachi, Abbott, Catalano, Haggerty, & Fleming, 1999). It has become increasingly important to move beyond a ‘black box’ approach to program evaluation (McLaughlin, 1987; Patton, 1979) by focusing on aspects of implementation and not just on program impact. This attention also helps to distinguish what pertains specifically to the program and what pertains to the way in which it was implemented (e.g., program failure versus implementation failure). Process evaluations are one of the main ways to gather information on the favourable conditions and challenges surrounding implementation (e.g., the manner in which the program was, or was not, successful in reaching the target group; delivering the proper training to staff; and/or adequately delivering activities while respecting dosage requirements). The data from process evaluations can provide important details about the way in which a program is implemented (Savignac & Dunbar, 2014), which in turn can help to explain the achievement of desired results, or not. These implementation findings can help to better understand and promote the conditions and circumstances necessary to produce intended outcomes moving forward.

To summarize, implementation science considers the research findings of evidence-based practices to improve the quality and effectiveness of specific programs and services. In examining each part of implementation and the unique implications and considerations for Indigenous peoples, this literature review sought to highlight and bring forward the importance of recognizing the historical experience of Indigenous peoples and the impacts on crime among the latter. Additionally, it demonstrated how culture, community, and traditional knowledge contribute to the development of effective crime prevention programs. Finally, it highlighted how process evaluation can be used as a tool to better understand program implementation, and identify strategies to promote program success. The current research study aims to contribute to the body of knowledge related to the implementation of crime prevention projects aimed at serving Indigenous populations.

Methodology

Research Design and Sampling Process

This research study employed an exploratory research design whereby the implementation process for crime prevention projects aimed at serving Indigenous populations were examined and described in detail. This was completed through the review and analysis of process evaluation reports for crime prevention projects funded through Public Safety Canada (PS)’s National Crime Prevention Strategy (NCPS). The purpose of this review was to examine the information that currently exists related to the implementation process, to provide an in-depth understanding of the associated challenges and strategies, and to identify possible recommendations for moving forward. This work offers a contribution to the field of implementation science through the collection and presentation of information and key findings as it applies to crime prevention programs aimed at serving Indigenous populations.

The sample used for this research study was comprised of 49 process evaluation reports of crime prevention projects funded through the NCPS. To be included in the sample, projects needed to be focused on Indigenous populationsFootnote3 and have a completed process evaluation report available for review. This information was retrieved from an implementation repository initially created for PS under an external research contract (Currie & Roberts, 2015Footnote4) that collected implementation data from crime prevention projects funded through the NCPS between 2008 and 2014. Forty-four (44) projects meeting the inclusion criteria were selected from this repository. An additional five (5) projects that concluded by the end of 2019 and met the inclusion criteria were added to the sample by PS staff members.

Data Collection

Modelling after Currie and Roberts’ (2015) approach to examining program implementation, the identification of key implementation data to be collected was undertaken in multiple phases. The first phase involved the review of pertinent implementation literature and PS reference documents to better understand implementation science and crime prevention programs, followed by a detailed reading of each included process evaluation report. Furthermore, using a repository coding guide and a validated data collection form prepared by PS, data was collected retrospectively from existing projects’ process evaluation reports. Data collection forms were completed for the 49 projects, as identified above. Reports were scanned several times prior to coding the relevant information into the data collection form. Information reviewed related to project description, location, participation, referrals and assessments, management, planning, staff recruitment, volunteers, partnerships, evaluation, fidelity, implementation challenges/successes, and lessons learned. After the information was collected in the data collection forms, it was input into a Microsoft® Excel database, where every part of the data collection form was represented and all aspects of the implementation process were captured in detail. The coded items were presented numerically, other than data that could only be presented through text. The latter related to project planning and management, services provided, participant involvement, engagement and retention, data handling, and overall implementation challenges.

Quality of Research

To ensure the trustworthiness and rigor (i.e., reliability and validity) of the qualitative findings, a peer review process was employed where a second individual reviewed and confirmed the interpretation made by a first individual who was primarily responsible for analyzing the data (Patton, 2015; Tobin & Begley, 2004). Reliability was ensured through successive review by one individual (test-retest reliability) and simultaneous review by more than one individual (inter-rater reliability). Certain process evaluation reports were examined and coded numerous times to retrieve all necessary information. Content validity, or how accurately the assessment or measurement distinguished the specific construct in question (Content Validity: Definition, Index & Examples, 2015), was also examined. This research study was designed to measure and analyze specific content (i.e., retrieve implementation information from process evaluation reports) and using the repository coding guide and data collection form, it was in fact able to measure the specified content.

Data Analysis

Microsoft® Excel (Excel) and QSR International NVivo 10 (NVivo) were used for storing and analyzing data retrieved from the process evaluation reports. The analysis began by using the Excel database to generate descriptive statistics for quantitative information. Specific cells relating to the type of program activities, location, participants, recruitment and retention of participants, project fidelity and adaptation, and partners, were selected.

Data requiring thematic analysis was completed using NVivo. The Excel database was uploaded to NVivo and all information coded under the cells of implementation challenges and strategies, and lessons learned were coded. Of these three categories, sub-themes (nodes and sub-nodes) were created to sufficiently represent the data. Each was created by examining and analyzing the data and understanding the themes that frequently emerged. Query functions were used to question the coded data in NVivo and identify specific data relating to a particular area. Further analysis examined frequency, severity, and irregularities, among other things.

Methodological Limitations

The process evaluation reports varied in terms of project goals, targeted age groups, risk factors, fidelity tools, dosage guidelines, and evaluation design. It is important to note that due to these varying evaluation designs and the extent of implementation challenges, some evaluations primarily reported qualitative information, while others reported statistically significant results and more robust findings.

Description of Projects and Services Delivered

To understand how implementation is affected, it is vital to examine the various aspects that contribute to it. Each project has its own way of operating and method to deliver services. This is explained by the fact that the “contexts in which implementation efforts occur are themselves complex because of multiple interacting levels with wide variation from setting to setting” (Bauer et al., 2015, p. 5). Although each project aims to serve an Indigenous population, each is implemented independently, using different program models, which in turn impacts the services delivered. Projects incorporated different elements and activities, were located in urban, rural, or small communities, and served children, youth, and adults. The varying results of implementation are characterized by the differences in their areas, among others. This section provides an overview of the type of programs, location and setting, elements provided, and the characteristics of participants.

Types of Programs

All 49 projects were classified into one of three types: model, promising, and innovativeFootnote5. The majority of projects (70%, 34) were classified as promising and innovative, each representing approximately one third (35%, 17) of all projects. These include projects such as the Leadership and Resiliency Program, Project Venture, the Youth Inclusion Program, the Wraparound Approach, Alternative Suspension, Pathways to Education, Project L.E.A.D, Reconnecting Youth, Cadet Corps, Innovative Program, and Gang Prevention Through Targeted Outreach.

Project Locations and Primary Setting

Projects were delivered across Canada and were implemented in most provinces and territories. The majority of projects (65%, 32) were concentrated in four provinces: British Columbia, Alberta Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. Approximately one third (37%, 18) of projects were located in Northern CanadaFootnote6, of which half (51%, 25) were in remote or isolated communitiesFootnote7. Many projects were implemented in small communities (43%, 21), while the rest were implemented in primarily urban, primarily rural, or mixed settings.

Projects were delivered in different settings and by a variety of organization types (e.g., school, health, recreation, youth justice, social service). Many projects were school-based (33%, 16) and delivered within a community, recreation, and/or youth facility setting (37%, 18). Often teachers incorporated project elements into the education curriculum, using school facilities and materials, in addition to having organizations and/or community centres host the project’s activities.

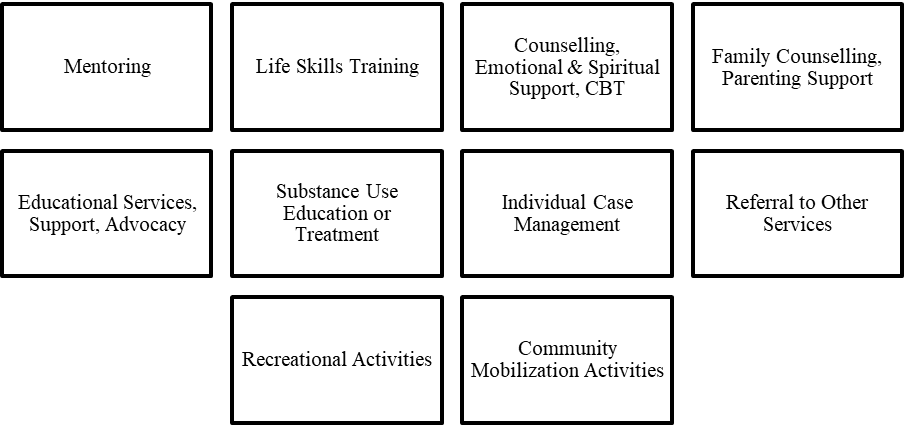

Service Elements Provided by the Projects

There were 10 main service elements included in project implementation depending on the individual project (see Figure 1). These included the following: mentoring; life skills training; counseling, emotional and spiritual support, and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT); family counseling and parenting support; educational services, support, and advocacy; substance use education or treatment; individual case management; referral to other services; recreational activities (e.g., field trips, sports, outdoor activities), which aim to combine amusement with other program components; and community mobilization activities, which allow community organizations to offer their help and support. Mentoring, life skills training, and counseling services and other forms of therapy, were activities delivered in most projects (71%, 35). Service elements were delivered by project management and/or coordinators, staff (counsellors, psychologists, other professionals), volunteers, teachers, community partners, Elders and other Indigenous partners, and law enforcement. It is important to note that participants were most satisfied with having Indigenous staff deliver the service elements and having cultural elements included. As well, elements focusing on mental health, addiction, and basic skills development contributed to the overall level of satisfaction of participants and their families.

Figure 1. Service Elements

Image Description

Figure 1 displays the 12 main service elements included in project implementation. Each square is presented in order by frequency of delivery. The first row includes the services delivered in most projects, including: mentoring; life skills training; counselling, emotional and spiritual support, CBT; and family counseling, parenting support. The second row includes: educational services, support, and advocacy; substance use education or treatment; referral to services; and individual case management. The third row includes: community mobilization; and recreational activities.

Characteristics of Program Participants

The primary crime issues that these projects sought to address included: bullying; gang violence/gang criminal activity; intra-family violence; drug/alcohol related crime; hate/bias crime; violence (non-family); sexual exploitation; property crime; and gun/weapon crime. Other participant focused issues included: challenges with basic needs (lack of food security, employment, addiction); physical/mental health; family, school, socio-economic issues; and criminal behaviours, including violence. Project participants faced unique and challenging life circumstances (documented through the identification of many risk factors and few protective factors) creating an increased risk for offending. In addition, projects offered provisions to address other participant needs, for example, providing snacks and meals, transportation, after-school care, and school supplies.

Participants came from a variety of Indigenous communities, including First Nations, Inuit, and Métis. Languages spoken by participants included Indigenous languages (e.g., ᐊᓂᐦᔑᓈᐯᒧᐎᓐ / Anishinaabemowin / Ojibway, ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ / Nēhiyawēwin / Cree, Tłı̨chǫ Yatıì / Tlicho / Dogrib, ᓇᔅᑲᐱ / Nakaspi) and English, and certain projects involved the use of translation services to implement project activities. Projects were delivered to both boys and girls and the majority were delivered to youth aged 12-17 (63%, 31). Of these participants, the majority had mental health, drug-alcohol issues, and were at risk of offending or reoffending (67%, 33).

Detailed Results

Using descriptive statistics and the information retrieved from the coding process, this section examines and analyzes categories linked to the implementation of projects aimed at Indigenous populations, capturing the challenges but also highlighting the successes. The categories discussed below include recruitment and retention of youth participants, project fidelity and adaptations, relationships with partners (community organizations, Indigenous organizations, schools, and police) and their engagement, implementation challenges and strategies to overcome them, as well as lessons learned for project implementation.

Recruitment of Youth Participants

Approximately half of the projects (49%, 19) included in this research study described one or more challenges related to the recruitment of youth participants, including the following: low number of referrals; unwillingness of family to complete forms; difficulties engaging highest-risk youth and securing family commitment; youth and families suspicious of service providers and a lack of trust in the program; program activities in competition with other school and extra-curricular commitments; and a high level of staff turnover.

To address these challenges, facilitative strategies were put in place in many cases, increasing the time and effort dedicated to outreach activities (e.g., informal contact with program staff in the community, information sessions delivered in schools, door-to-door communication with families). It should be noted that in the cases with issues related to recruitment, only one third of projects (33%, 16) provided strategies to address the challenges.

Retention of Youth Participants

More than half of the projects (55%, 27) identified challenges related to retaining their participants in program activities, including the following: complex and challenging lives of youth that served to disrupt their attendance; their disinterest in structured activities (especially older youth); activities in competition with other school extra-curricular commitments; being distrustful of the ‘system’; worker fatigue and staff turnover that disrupted participant trust; a lack of parental involvement; participants stopped contact with the program, received long-term custodial sentences, or were deceased; lack of transportation; youth outgrew the program or graduated from school; and conflicts with other youth in the program and/or issues related to stigma.

Approximately half of the projects (51%, 25) described the specific strategies that they used to maintain participant involvement in program activities, including: school presentations and announcements to advertise the program and speaking with youth; fostering engagement through the introduction of Indigenous cultural elements and activities; offering incentives to both youth and their parents such as meals, transportation, and child care; being flexible with program activities such as offering a variety of educational and on-the-land activities and involving youth in decision-making and planning; and promoting a strong level of trust between staff and participants and attending to complex needs.

Project Fidelity & Adaptations

Approximately one third of the projects (39%, 19) made some adaptations from the pre-established program model, and in the case of three projects (6%) many adaptations were made. Adaptations reflected the needs of individual projects and were highly variable. The most common adaptations involved dropping or reducing some elements of the program.

Adding cultural elements or making cultural adaptations to existing elements was noted in close to one third of the projects (29%, 14). This included: the addition of culturally appropriate activities such as feasts and ceremonies; the addition of cultural references and elements in the program curriculum; and the involvement of Elders in program activities.

A small number of projects (14%, 10) noted the addition of components or activities such as Wraparound elements, SNAP® components, life skills training components, recreational activities, crisis management components, and gender-based components. Other adaptations involved making changes to the outreach approach and system of engagement, and to program administration activities.

The primary reasons for adaptations to the projects stemmed from project challenges. These included: needing to add meaningful cultural content that was not previously included in these crime prevention programs; addressing the problems of parent and community involvement; and making modifications to increase the engagement of youth participants. Adaptions were also made to projects due to the lack of resources and service capacity – this sometimes involved reducing the number, type, and scope of program activities.

Almost half of the projects (41%, 20) indicated that there were aspects of implementation that limited the delivery of effective services to participants. The main issue was the lack of key staff or staff turnover, which led to disruptions and limited the delivery of some activities. Another important issue included the lack of space and/or a permanent facility to hold program activities and the absence of reliable transportation services to the program.

Relationships with Partners

A majority of the projects (80%, 39) reported having at least one partner that contributed to the implementation of the program. From these projects, approximately one third (31%, 12) had 1-5 partners involved in some capacity, another third (39%, 15) had between 6-10 and 11-15 partners, a small number (10%, 4) had 16 or more partners, and one quarter (20%, 8) did not have any available data on the nature of their partnerships.

Community Organizations

Most of the projects (86%, 34) had partnership arrangements with community organizations. The main contributions made by the latter were the provision of speakers and trainers for the program and referrals, recruitment and assessment of participants, and providing the space and supplies for the program. In addition, other contributions included: making financial investments; collaborating on events; and providing transportation. For half of these projects (51%, 17), these partnerships appeared to be positive. The major challenges identified were limited referrals and less engagement than was originally planned. In order to resolve challenges, referral forms were simplified. Improving communication and networking between the project and partners was also identified as important for building strong relationships with community organizations.

Indigenous Organizations

Just over half of the projects (61%, 24) had partnership arrangements with Indigenous organizations. The main contributions made by the latter included: developing cultural programming and adaptations including Elder involvement; assistance with program planning and design as well as participation on advisory committees; and the provision of volunteers, facility space, equipment, and transportation for participants. For just over a third of these projects (37%, 9), these partnerships appeared to be positive. Available information on the types of challenges was limited but included: a lack of Band Council support; problems accessing funding; few or inconsistent referrals; and communication issues. Most of these issues appeared to be unresolved at the end of program implementation.

Schools

Most of the projects (86%, 34) had partnership arrangements with schools. The main contributions made by the latter were referrals of participants and provision of facilities/sites for program activities. For half of these projects (49%, 17), these partnerships appeared to be positive. The major challenges identified included: the reluctance of schools to fully engage; a high turnover with school staff; difficulty incorporating project components into education curriculum; lack of a strong, formal relationship; and lack of a thorough understanding of the program. In addition, school closures as a result of unforeseen problems (e.g., flooding) required certain programs to find new facilities. In some cases, projects offered information on how these challenges were addressed, including: the importance of establishing trust, buy-in and positive communication with the schools; and focusing on extra-curricular components and settings.

Police Services

Three quarters of projects (73%, 28) had a police service as a major project partner. The main contributions made by the latter included: providing referrals, recruitment, and assessment of participants; aiding in the creation of program protocols; and acting as volunteers or chaperones for various project activities and events. For a third of these projects (33%, 9), these partnerships appeared to be positive. Available information on the types of challenges was limited but included: weak engagement with the police; lack of information sharing; fewer referrals were made than originally anticipated; lack of trust and weak relationship; and the police had a different philosophy from the other partners.

Engaging and Motivating Partners

Approximately a third of the projects (31%, 12) provided information on the challenges of engaging partners. The most common challenge identified was the time and resources required to network and communicate sufficiently to maintain interest of partners and to build trust. Projects also indicated that partner organizations were often too busy to become meaningfully involved.

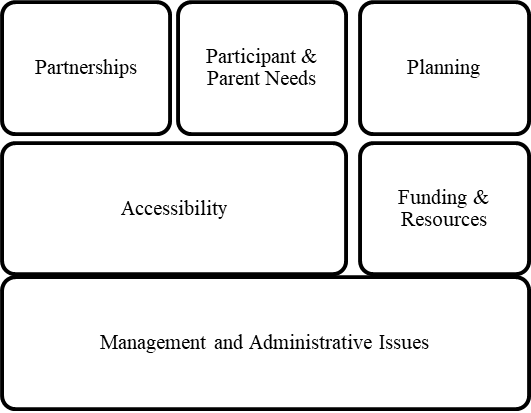

Most Common Project Implementation Challenges

Project staff and management aimed to successfully implement their program in line with their selected project model(s). Implementation challenges were noted in most projects (92%, 45), often due to factors related to community readinessFootnote8 and community mobilizationFootnote9. Frequently faced challenges included: program accessibility attributed to minimal transportation, poor weather conditions and securing a safe project location; lack of funding; management and administrative issues such as staff turnover, recruitment difficulties, and meeting minimum qualifications; lack of support and understanding from partners of the curriculum; and little time management and planning. Figure 2 provides an overview of these challenges and the size of each box denotes the general level of their prevalence among projects.

Figure 2. Implementation Challenges

Image Description

Figure 2 displays the implementation challenges and a general level of their prevalence across projects. Prevalence is denoted by the size of each box. Challenges experienced from most prevalent to least prevalent include: management and administrative issues; accessibility; funding and resources; partnerships; participants and parent needs; and planning.

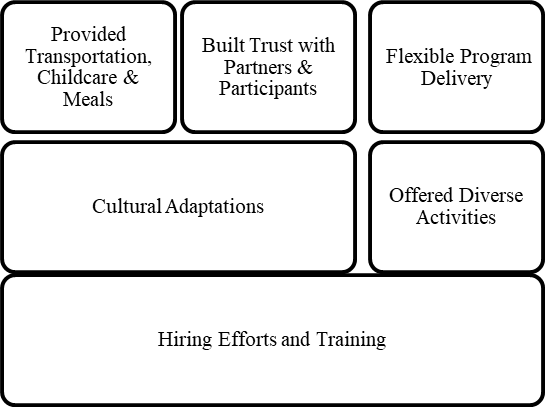

Most Common Strategies to Address Project Implementation Challenges

Several challenges were experienced throughout implementation, and strategies and approaches were employed to address these challenges. Approximately half of the projects (53%, 26) used implementation strategies. Those most frequently used included: building strong relationships through sustained communication and networking; providing additional training to staff and making efforts to hire more staff; offering diverse activities that were appropriate and interesting to youth; incorporating cultural teachings in materials and cultural activities/events where applicable; flexible program delivery to adapt to life challenges; and providing transportation, child care, and meals. Figure 3 provides an overview of these strategies and the size of each box denotes the general level of their prevalence among projects.

Figure 3. Strategies to Overcome Implementation Challenges

Image Description

Figure 3 displays the strategies to overcome implementation challenges and a general level of their prevalence across projects. Prevalence is denoted by the size of each box. Strategies used to address implementation challenge from most prevalent to least prevalent include: hiring efforts and training; cultural adaptations; offered diverse activities; provided transportation, childcare and meals; built trust with partners and participants; and flexible program delivery.

Lessons Learned for Project Implementation

Many projects offered information about the lessons learned or best practices they had identified in relation to successful program implementation. These learnings have been categorized into the areas of program development, participant groups, sponsor organization and staff, partners, and evaluation and are presented in detail below.

Program Development

- Flexibility to adapt the program model if needed is important (e.g., for isolated, remote and/or Northern communities or to encourage engagement and interest).

- It is important to include cultural-based activities, tools, and materials with Indigenous communities and to involve service providers in cultural programs.

- The selected program should consider the community’s characteristics (e.g., community contexts, program capacity, historical backgrounds, intergenerational trauma).

- In geographically large communities, transportation is a challenge and is required for program activities.

- Programs require adequate space and facilities to accommodate participants and deliver activities.

- Establishing a liaison between project management and staff, and an individual representing the community is fundamental to program success.

Participant Groups

- Increase engagement with parents (e.g., regular outreach, explain rationale for assessment procedures, provide support services, minimize reference to criminal behaviour).

- Engage effectively with youth (e.g., spend sufficient time, give practical support, adapt to their schedules, and meet youth where they are at physically and emotionally).

- Especially in isolated or remote communities, consider the provision of specific services (e.g., child stipend, meals, or childcare to enable participation).

Sponsor Organization and Staff

- To retain continuity of service and alignment of program activities, avoid burnout and reduce turnover (e.g., provide ongoing staff support and training, including for volunteers and Elders).

- Especially in isolated or remote communities, the organization needs stability (i.e., a ‘track record’ and history in the community), experience with target group and partners, and the ability to implement new and promising programs.

Partners

- It is important to understand partners and develop formal partner agreements, and to communicate about program philosophy and conditions for optimal partner participation.

Evaluation

- Program planning and design should involve a strategy that produces data to be used by the program evaluator.

- Project management and staff must ensure that accurate and complete documentation is available for the program evaluator.

- Ensure data base management capacity and systems are in place prior to project start-up to support ongoing monitoring and assessment of progress in line with the program’s goals.

Discussion

The literature review and the findings from this research study provide important information on the implementation process for crime prevention programs aimed at serving Indigenous populations and how to promote its success. This section thematically analyzes and describes the findings while considering the existing literature. This includes an analysis of program readiness and planning, resource limitations, culturally relevant adaptations, and the importance of formative evaluation.

Program Readiness and Planning

The reviewed literature detailed how program readiness and planning are primary measures of successful implementation. In fact, this research study found that certain challenges developed from a lack of community readiness and mobilization. This was partly related to the influence of community context and historical factors faced by Indigenous populations on project planning, and the willingness and ability of the organizations to implement and sustain the program.

As everyday life is rooted in culture and traditions, the impact of colonization and assimilation on Indigenous peoples has significant long-standing effects, such as loss of identity, and mental and physical health challenges, among others (Capobianco & Shaw, 2003; Grover, 2010; Homel et al., 1999). The implementation of crime prevention programs aimed at serving Indigenous populations has unique considerations related to community context, organizational capacity, and historical/systematic factors (e.g., systemic discrimination, intergenerational trauma). It is crucial that cultural responsiveness is considered when developing crime prevention initiatives as these issues directly impact Indigenous peoples’ experiences within the program and on the effectiveness of these programs. There is a need to be mindful of how each participant will experience program activities, and whether the activity is appropriate for participants. This research study found that staff who have experience working with the target group and are familiar with the community context are necessary for improving program participation. Also, of importance is the need for specific services (childcare, meals, transportation, allowances) that further support participation. The availability of these services has been observed to affect participant retention and recruitment challenges. Further, projects aim to address specific issues (e.g., bullying, gang violence/gang criminal activity, family violence, drug and alcohol-related crime, and hate crime, etc.). Focusing on other factors, such as basic needs and social support services, helps to address risk factors that contribute to criminality, but also supports the individual’s ability to participate in the program.

Effective youth engagement is necessary for participant recruitment, enrollment, and retention in crime prevention initiatives. This involves: adapting to youths’ schedules; understanding they might not be ready to open up; recognizing the importance of building trust and a relationship; giving practical support; and spending the time needed with participants. In fact, Grover (2010) explained that certain program models and funding agencies underestimate the time needed to fully establish and integrate the capacity building process in Indigenous communities. Difficulties with recruitment were associated with the community context, such as a lack of trust with project staff, and challenges encountered with participants’ families. Also noted were the burdensome requirements to complete certain documentation and assessment questionnaires during the intake process. Careful and considerate outreach and engagement are required, especially when working with a population that has experienced various forms of trauma, that may lead to a variety of day-to-day challenges. It is also important to note the role that the community context, personal experiences, recruitment strategies, and the intake process have on retention. The research evidence suggests several options, including: having less intrusive questioning; minimal documentation; more activities; less formal discussions; and components delivered during school hours. Modifying recruitment methods so they respect the needs of Indigenous peoples and the community enhances the likelihood of recruitment, and considers the community’s needs as a whole. Furthermore, projects experienced retention challenges due to the circumstances faced by the target population and circumstances that were beyond the control of staff. For example, participants graduating, involvement with the criminal justice system, losing interest in program activities, participant stigma, challenges between participants, or moving away were noted. Projects did not determine strategies for these specific circumstances. As a result, projects were delayed in trying to recruit more participants and develop strategies. Project management should seek to find ways to continue engaging participants even when attendance and retention is low.

An element that may also be part of the planning process is the development of community safety plans, which are a means to determine community readiness. These plans determine what is required from the community, partners, and by extension project staff in order to address crime and safety issues. They ensure that the appropriate tools, strategies, and training and supports are available. In fact, “Indigenous communities develop tailored approaches to community safety that are responsive to their concerns, priorities, and context” (Public Safety Canada, 2019, p. 1). These plans require the engagement and involvement of the community and community leaders. Grover (2010) noted the importance of including the community in project planning from the beginning of the project. An important contextual factor to consider in project planning is community readiness, which affects program success. Furthermore, there are six core principles essential to inform community safety plans: (1) be holistic; (2) be culturally relevant; (3) encourage community involvement; (4) recognize the gifts and strengths of individuals and the community; (5) be respectful of each community’s current state of development; and (6) be developed by and for Indigenous peoples (Public Safety Canada, 2019). These guiding principles contribute to the inclusion of key community elements, to promote and address specific community issues.

Ensuring the sustainability of crime prevention projects in Indigenous communities is essential to fostering long lasting positive outcomes and relationships, but remains a challenge. Projects often face obstacles to sustainability including time-limited funding, reduced resources, and limited community support. A strong and sustainable program requires the following: ongoing funding and resource development; building and maintaining effective partnerships; ensuring effective leadership and staff commitment; fostering community buy-in and participation; maximizing program quality and effectiveness; and prioritizing good communication and visibility (Bania, 2014). Emery (2000) found that in planning for sustainability, projects should include Elders and women, consider the environmental impact and changes faced by program participants, and take time to understand the cultural etiquette of the community. Similarly, Bania (2014) noted the advantage of getting to know the community in terms the following: its diversity; perceptions of the program; to set clear expectations; and to show appreciation and recognition. These considerations for sustainability should be incorporated into the project planning phase. Moreover, organizational capacity may only allow the program to be implemented over the duration of its funding allocation. In this case, there is the possibility to incorporate program components into activities of project partners. For example, adding activities into school lessons, organizing cultural outings and activities with community centres, and distributing program resources to inform the community. In sum, efforts for sustainability include early discussions to help identify and secure funding from current partners and other community organizations, connecting partners, and allowing sufficient time to plan and organize for program sustainability.

Resource Limitations

In combination with program readiness, there are resources necessary for program implementation. This includes both financial and in-kind resources such as management and staff and partnerships with community organizations. There is a requirement to have certain resources in place for effective program delivery, adaptation, and sustainability. The research literature and the findings from the current research study demonstrate that resource limitations directly impact the implementation of crime prevention programs. The challenges identified in several projects included staff recruitment, finding qualified staff, staff turnover, and lack of understanding and support from partners. In order to address these common challenges, having a specific staff-related contingency plan will allow for project management to effectively address staff turnover, vacancies, and who will temporarily cover off additional tasks.

The findings demonstrate the challenges in staff recruitment and hiring qualified staff. As a result, there were delays to project start-up and service delivery. In fact, the majority of these projects were located in Northern Canada, in small and remote communities. This type of location made it challenging to find staff with specific qualifications for service delivery (psychologists, social workers), and staff who could commit the time required to program implementation. Projects aimed to address recruitment issues through incentives, such as providing lodging for staff who came from other communities. Research has demonstrated that project success increases when management and staff have experience working with the target population, are well informed on the program, and undergo training to further develop the skills necessary for the position (Cunneen, 2001; Fixsen et al., 2005). Further, greater outcomes for the target population occur when projects have qualified staff, with a clear understanding of the services to be delivered.

Staffing challenges (turnover and retention) were found to delay the implementation of project components. In fact, program time and resources were diverted to filling staff vacancies and finding specialized staff. These issues are of concern when considering implementation because of the increased resources required for additional training and clinician support (Aarons et al., 2009). The current research study found that staff turnover meant that remaining staff covered several positions, which they might not have been qualified nor trained for (McKay et al., 2019). This related to the organizational pressure that staff experienced in maintaining project continuity. As a result, staff are more likely to experience burnout due to increasing demands and having limited access to staff support services. One reason for staff turnover is when management decisions do not consider staff needs (Aarons et al., 2009), often impacting the overall productivity and morale of the remaining staff. The direct impact on projects included the following: delays in activity delivery; activities were delivered differently or inconsistently, due to a lack of training; new start to relationship-building; youth stopped attending activities; and certain participants’ psychological needs could have been missed as a result of few qualified staff. The beginning phases of project planning should include key considerations such as these, so that project resources do not limit implementation. Approaches to minimize delays caused by staffing challenges include: early staff recruitment; a project design considering different staffing complements; dedicated staff resources and support services; and backup plans noting possible challenges and the strategies to address them.

In addition, partners played an important role in the success of implementation. Partners are a major contributor of program resources (financial investments, in-kind contributions), transportation, delivery, and the provision of staff. Partners were involved in a majority of the projects included in this research study, although many reported experiencing difficulties with engagement. The majority of partnerships were with schools, and Indigenous and community organizations. The main challenge was for the partners to clearly understand the program and their role in the latter, which contributed to difficulties in consistent program delivery. For example, many teachers indicated lacking the time and effort required to implement program components in their classes, which in part came from having little knowledge and understanding of the program itself. Additionally, although many Indigenous partners helped develop and deliver cultural programming and adaptations, there was little support from Band Councils. Band Councils hold the necessary skills and knowledge to connect youth with their heritage (traditional hunting, gathering, ceremonies). This demonstrates an opportunity to develop further training and other resources to support partners and staff. Additional resources help to support staff so they are equipped with the necessary tools to deliver program components, have reference materials, and to ensure that program components are delivered consistently. In some instances, the lack of understanding led to program components not being delivered properly or delivered at all. This created tensions between partners and project management, as partners are usually volunteering their time. For teachers, they are occupied with other course curriculum requirements and obligations. Other challenges with partners made it difficult for staff to be prepared and to make certain adaptations for participants, such as the lack of information sharing and referrals. Knowing participants’ background information can help partners in the delivery of activities and the impact on the community. Knowledge and information sharing between project management, staff, and partners promotes open communication. Developing partner agreements and promoting ongoing communication throughout the duration of the project, are strategies found to facilitate greater partner participation.

Culturally Relevant Adaptations

Culture is an important protective factor for Indigenous peoples, as cultural values lay the foundation for resilience, and are positively associated with health and social outcomes. These include: personal wellness; positive self-image; self-efficacy; familial and non-familial connectedness; positive opportunities; positive social norms; and cultural connectedness (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019). Cultural factors can be incorporated into crime prevention programs, for example including aspects of Indigenous cultures in program components, having Indigenous staff, and making culturally relevant adaptations where needed. As well, the addition of cultural aspects to crime prevention programing helps to acknowledge unique historical factors and particular community context. Understanding how culture impacts specific situations is at the centre of culturally-relevant adaptations. For example, considering the social determinants of health (e.g., income, education, employment, mental health), examining traditions and celebrations, and understanding the political climate. There are a range of contextual factors influencing implementation, interacting with each other, and changing over time. This highlights that implementation often occurs as part of a complex adaptive system (Peters et al., 2013).

Additionally, it is important for projects to recruit Indigenous staff and/or volunteers. This would encourage trust and relationship building between staff and participants, which is a significant part of Indigenous cultures. This research study identified challenges with participation and retention due to the lack of trust between participants and staff. Although staff worked toward building relationships, having Indigenous staff can encourage and promote a greater sense of trustworthiness. Indigenous staff can help to motivate greater engagement by encouraging participants to communicate in their language, making them more inclined and comfortable to open up, to share commonalities with staff, and be better equipped to deliver cultural activities. Moreover, staff coming from other types of communities might not understand the life complexities and challenges faced by the program participants. In fact, this research study noted the difficulties in trust and relationship building between participants and staff coming from outside of Northern Canada and small communities.

Several projects noted that adaptations were made throughout implementation, and these were largely in response to project challenges (e.g., lack of resources and service capacity). This may be explained in part by a project’s lack of engagement with and from partners and organizations. This demonstrates the need to develop community engagement initiatives during planning and implementation. It may also be explained by the fact that evidence-based programs are often applied in Indigenous communities without a requirement for adaptations to address the community contextual differences (Jernigan et al., 2020). Project management must recognize the disparities that exist among communities and participants when looking to make adaptations. From the start, program adaptations must recognize the differences among participants and the community and find ways to keep the key aspects of the program model to ensure its effectiveness. This involves researching, developing an understanding, and making changes where possible to best fit the culture(s) of the target population.