Evaluation of Risk Assessment Tools for Indigenous Individuals with a History of Sexual Crimes: A Response to Ewert case (2018)

By Seung C. Lee, R. Karl Hanson, and Julie Blais

Table of contents

Abstract

In Canada, the issue of cultural bias in risk assessment tools is an ongoing concern, particularly for Indigenous peoples who are overrepresented in the criminal justice system. To date, there has been relatively little research on the validity of structured risk assessment tools for Indigenous peoples. This study examined the predictive accuracy (discrimination and calibration) of two risk assessment tools (the Static-99R and Static-2002R) used with White individuals (n = 1,560) and persons of Indigenous heritage (n = 653) who have a history of sexual crimes from five independent Canadian samples. The results indicated that the Static-99R predicted sexual recidivism with similar accuracy for Indigenous peoples and White individuals. The Static-2002R predicted sexual recidivism only for White individuals. The domains of persistence/paraphilia and youthful stranger aggression were not as predictive for Indigenous individuals as for White individuals; however, the general criminality domain predicted sexual recidivism for both Indigenous and White peoples. Furthermore, results suggested that White individuals had more indicators of paraphilic interests whereas Indigenous peoples displayed higher indicators of general criminality. The findings suggest that the treatment for individuals at risk for sexual offending may benefit from an increased focus on distinctive risk-relevant characteristics of White individuals and Indigenous peoples in the criminal justice system.

Keywords: sexual offending, Indigenous peoples, Static-99R, Static-2002R

Author's note

The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institutions that supported this research. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to:

Seung C. Lee

Department of Psychology, Carleton University

1125 Colonel By Drive

Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6

Email: seungc.lee@carleton.ca

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

R. Karl Hanson is a co-author and certified Static-99R and Static-2002R trainer. The copyright for Static-99R and Static-2002R is held by the Government of Canada, and none of the authors receives royalties from this measure.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Patti McDonald and Leticia Gutierrez for their helpful feedback on an early version of this article. We would also like to thank the following researchers for permitting us to use their data: Jim Bonta, Andy Haag, and Mark Olver.

Introduction

The purpose of the Canadian correctional system is to administer sentences, promote public safety, and assist in the rehabilitation of offenders (Corrections Act, 1988; Corrections and Conditional Release Act, 1992/2012; Ministry of Correctional Services Act, 1990). Forensic risk assessment has become a ubiquitous practice in achieving these goals, from determining whether offenders should be incarcerated in higher security settings (e.g., Dangerous Offender hearings; ss. 752 and 753 of the Criminal Code of Canada) to deciding who should be released on parole. According to the Risk principle of the widely accepted Risk, Need, and Responsivity model of offender rehabilitation (RNR), treatment programs are most likely to be effective when the most intensive services are provided to the highest risk offenders (Andrews, Bonta, & Wormith, 2006; Andrews & Bonta, 2010; Gendreau, Smith, & French, 2006). Consequently, accurate assessments of recidivism risk are a prerequisite for effective offender rehabilitation.

An ongoing concern of the assessment of recidivism risk is the extent to which measures, developed and validated using predominantly White samples, can be applied to other ethnic and racialized minority groups (i.e., cultural bias). In Canada, the issue of cultural bias has mostly concerned individuals of Indigenous heritage, who are overrepresented at all stages of the criminal justice system (Haag, Boyes, Cheng, MacNeil, & Wirove, 2016). This issue has received renewed attention with the Ewert v. Canada (2015, 2018) case where the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that several well-known risk assessment scales (e.g., Static-99; Hanson & Thornton, 2000; Psychopathy Checklist-Revised [PCL-R], Hare, 2003) had insufficient evidence on cross-cultural validity to justify their use with Indigenous peoples with a history of crime.Note1

Given this context, the purpose of this study was twofold: 1) examine the potential for cultural bias in the predictive validity of two widely adopted scales for individuals with a history of sexual crimes (i.e., Static-99R [Hanson & Thornton, 2000; Helmus, Thornton, Hanson, & Babchishin, 2012] and Static-2002R [Hanson & Thornton, 2003; Helmus, Thornton, et al., 2012]), one of which was specifically named in the Ewert case; and 2) assess the presence and predictive validity of the psychological constructs that underlie these scales. This study represents the largest and most up-to-date evaluation of both the Static-99R and Static-2002R with individuals of Indigenous heritage. It is also the only study of these measures to examine both discrimination (i.e., relative risk) and calibration (i.e., absolute risk) as indicators of predictive validity.

Indigenous Overrepresentation in Canadian Corrections

Despite accounting for approximately 4% of the total Canadian adult population (Statistics Canada, 2015), Indigenous peoples (First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) account for more than 20% of the total offender population (i.e., in custody and in community under supervision; Public Safety Canada, 2018) and 23% (444/ 1,898) of individuals serving a federal sentence for a sexual offence (MacDonald, 2014). Furthermore, Indigenous peoples in the criminal justice system are more likely to be placed in higher security prisons (Public Safety Canada, 2018), less likely to be granted statutory release (i.e., released after 2/3 of their sentence; Public Safety Canada, 2018), and more likely to have their parole revoked (Office of the Correctional Investigator, 2018).

There are several proposed reasons for the overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in Canadian corrections. First, research has consistently found that Indigenous peoples are more likely to be arrested and convicted than non-Indigenous peoples (e.g., Bonta, Laprairie, & Wallace-Capretta, 1997; Quann & Trevethan, 2000) and have significantly higher recidivism rates (Gutierrez, Wilson, Rugge, & Bonta, 2013; Rojas & Gretton, 2007; Sioui & Thibault, 2002). An important finding for the current study is that Indigenous individuals in the criminal justice system score higher on the majority of established risk factors for general and violent recidivism than non-Indigenous individuals (i.e., Central Eight risk/needs factors; Andrews & Bonta, 2010). For example, Indigenous individuals in the criminal justice system have lengthier criminal histories (e.g., Holsinger, Lowenkamp, & Latessa, 2006; Perley-Robertson, Helmus, & Forth, 2018; Shepherd, Adams, McEntyre, & Walker, 2014), higher rates of substance abuse (e.g., Ellerby & MacPherson, 2002; Shepherd et al., 2014), more problems with family/marital relationships (e.g., Shepherd et al., 2014; Trevethan, Moore, & Rastin, 2002), and less education/employment (Holsinger, Lowenkamp, & Latessa, 2003; Shepherd et al., 2014; Trevethan et al., 2002) than non-Indigenous individuals in the criminal justice system.

The presence of these risk factors is not surprising when we consider that, in comparison to non-Indigenous peoples, Indigenous peoples have lower median incomes ($25,526 vs. $34,604), lower employment rates (52% vs. 60.5%), lower education levels (62% with a high school diploma vs. 80%; Statistics Canada, 2018), and poorer health outcomes (e.g., mental health issues and short life expectancy; Statistics Canada, 2005; Statistics Canada, 2015). It is also well documented that Indigenous peoples report higher rates of childhood maltreatment (neglect and sexual/physical abuse) and intimate partner violence (Boyce, 2016; Scrim, 2010; Sinha et al., 2011). They are also more likely than non-Indigenous peoples to be victimized according to official crime statistics (Boyce, 2016; Scrim, 2010; Sinha et al., 2011).

These indicators of adversity and social disadvantage need to be understood in the context of Canada's history of colonization and the devastating effects of racist social policies towards Indigenous peoples (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015). As the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) makes clear, many of the most pressing problems in Indigenous communities are predictable consequences of the efforts of the dominant social class to eliminate Indigenous cultures (i.e., residential schools, the Indian Act, and enfranchisement, wherein the Canadian government would strip Status Indians of their status if they obtained a university degree, served in the armed forces, or if a Status Indian woman married a non-Indigenous or non-status person). Whether it is poverty, substance abuse, low levels of formal education, or alienation and isolation, the criminogenic factors that contribute to higher rates of crime among Indigenous peoples in Canada are rooted in some 500 years of Indigenous-settler relations. To quote the RCAP (1996):

People who endure these disruptions may feel adrift - disoriented and unsure of how to get along in the sometimes hostile non-Aboriginal world. If their aboriginality has been devalued or ridiculed, they may have lost pride and self-esteem and be unable to build these qualities in their children. If they have been damaged in heart and soul, they may turn to alcohol, violence, crime or other forms of anti-social behavior (p.36).

The creation of the reserve system has further marginalized Indigenous communities and fostered environments conducive to crime for the following reasons:

- the reserve system creates large groups of disadvantaged people with limited resources;

- these communities tend to exist separate from mainstream society creating the potential for culture clash (e.g., differing views of crime and justice); and

- individuals in this environment are more likely to experience early and sustained abuse (Laprairie, 1996).

Although such conditions do not describe all First Nation Communities, there was no question that the reserve system placed non-Indigenous peoples in control of most of Canada's natural resources – natural resources for which Indigenous people continue to be dependent upon.

Another factor that may lead to Indigenous overrepresentation is the effect of systemic discrimination and bias in how Indigenous individuals are treated at all levels of the criminal justice system (R v. Gladue; Rudin, 2009; Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015). For example, there is evidence of differential treatment of Indigenous peoples in policing (i.e., higher likelihood of arrest), sentencing (i.e., longer sentences), and rehabilitation (i.e., reduced access to culturally appropriate programming; LaPrairie, 2002; Mann, 2009; Rudin, 2009). Underlying this discrimination is the false assumption that Indigenous individuals, just because of their race, are more likely to commit a crime (i.e., higher risk) than non-Indigenous individuals.

Risk Assessment and Cultural Bias

Considerable research has demonstrated that structured approaches to risk assessment, particularly those based on statistical methods (i.e., actuarial), provide a more accurate estimate for the likelihood of recidivism than unstructured judgments (Ægisdóttir et al., 2006; Grove, Zald, Lebow, Snitz, & Nelson, 2000; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2009). Risk assessment scales are criterion-referenced measures because the main goal is to assess the likelihood of a specific outcome in the future. Unlike norm-referenced scales, where the goal is the assessment of a specific construct, predictive validity becomes the most important metric for evaluating the efficacy of criterion-referenced measures (Gutierrez, Helmus, & Hanson, 2016). A comprehensive understanding of predictive validity considers both discrimination (how likely offenders with a higher score are to reoffend than offenders with a lower score) and calibration(how well the estimated recidivism probability from the instrument's norms corresponds with the observed recidivism probability of a new sample).

The Canadian Code of Ethics for Psychologists (Canadian Psychological Association, 2017) states that psychologists need to ensure that assessment methods are appropriate to the particular cultural and social contexts of the individuals being assessed (p. 20). Nevertheless, relatively little research has examined the cultural bias in structured risk assessment instruments. Cultural bias in risk assessment occurs when either discrimination or calibration is systematically different across ethnic groups (Reynolds & Suzuki, 2013). There are several possible causes for the cultural bias in the performance of risk assessment instruments. When looking at cultural bias within the instrument itself, we can refer to both item bias and construct bias (Geisinger & McCormick, 2013; see Haag et al. [2016] for a more thorough review). Item cultural bias refers to differential responses based solely on the cultural interpretation of the content of the item itself (e.g., the term "unrelated victim" could mean something different to someone from a more collectivistic culture). Construct cultural bias occurs when the constructs measured by the scale do not equally apply to individuals with different cultural backgrounds (Geisinger & McCormick, 2013). This could be an indication that the items meant to measure a specific construct are different for different ethnic groups, or that constructs may only partially apply to members of different groups (Byrne et al., 2009).

Until recently, relatively little research attention had been devoted to the validity of structured risk assessment instruments for individuals of Indigenous heritage. This, of course, changed with the Ewert case. Mr. Ewert, a Métis, serving two concurrent life sentences for sexually motivated homicide and assault, challenged the use of psychological and actuarial risk assessment instruments (e.g., Static-99) by the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC). The claim was that Mr. Ewert's rights under s. 24(1) of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (i.e., the use of accurate and up to date information) and ss. 7 (i.e., right to life, liberty, and security of the person) and 15 (i.e., equality before and under the law) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms were violated given that the instruments were not adequately validated for use with Indigenous peoples (Ewert v. Canada, 2015).

The original complaint resulted in a victory for Mr. Ewert; however, this decision was overturned on appeal. The case, therefore, proceeded to the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) where it was determined that, although Mr. Ewert's Charter rights were not infringed upon, the court made a declaration that CSC had failed in its duties under s. 24(1). More specifically:

The CSC had long been aware of concerns regarding these tools exhibiting cultural bias yet took no action to confirm their validity and continued to use them in respect of Indigenous offenders, despite the fact that research would have been feasible. In doing so, the CSC did not meet the legislated standard set out in s. 24(1)(Ewert v. Canada. 2018; pp.7-8).

In addition to the Ewert case, longstanding concerns about Indigenous over-representation has motivated repeated calls for more and better research (e.g., Mann, 2009; Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2016).

Risk Assessment with Indigenous Individuals with a History of Sexual Crimes

Structured risk assessment instruments consist of empirically identified risk factors associated with the recidivism outcomes (e.g., violent or sexual recidivism). There are two broad categories of risk factors: static (unchangeable) and dynamic (changeable) risk factors. In the criminal justice system, risk assessment instruments are widely used to estimate the likelihood of recidivism risk (i.e., prediction; static and/or dynamic risk factors) and to guide the effective intervention strategies (i.e., risk reduction; dynamic risk factors; Heilbrun, 1997; Neal & Grisso, 2014).

Within the last few decades, important risk factors associated with sexual recidivism have been identified based on samples of predominantly White people. These risk factors can be organized into two broad categories: indicators of general antisociality (e.g., impulsiveness, supervision failures, criminal history) and sex crime specific indicators (e.g., sexual preoccupation, emotional congruence with children; Hanson & Bussière, 1998; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2005; Mann, Hanson, & Thornton, 2010; Whitaker et al., 2008). When examining the risk profile of Indigenous individuals with a history of sexual crime, they tend to score significantly higher on general antisociality while scoring lower on sexual deviancy compared to non-Indigenous individuals (Babchishin, Blais, et al., 2012; Ellerby & MacPherson, 2002; Helmus, Babchishin, Blais, 2012). They also tend to be younger and have higher sexual, violent, and general recidivism rates (e.g., Babchishin, Blais et al., 2012; Rastin & Johnson, 2002; Rojas & Gretton, 2007).

Few studies have examined the predictive validity of risk assessment scales with Indigenous peoples with a history of sexual offending. Olver and his colleagues (2018) demonstrated that the Violence Risk Scale - Sex Offender version (VRS-SO; Wong, Olver, Nicholaichuk, & Gordon, 2003) significantly predicted sexual recidivism for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals with a history of sexual crimes. They further demonstrated that treatment change was significantly related to reductions in risk for both groups. In contrast, Helmus, Babchishin, et al. (2012) found that the STABLE-2007, another dynamic scale, did not predict sexual recidivism for Indigenous individuals with a history of sexual crimes. Their results were mostly attributed to the poor performance of the general criminality items; sexual deviancy items performed equally well for Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals.

Static-99R and Static-2002R are the most commonly used actuarial risk tools for adult males with a history of sexual crimes in Canada (Bourgon, Mugford, Hanson, & Coligado, 2018) and the U.S. (Kelley, Ambroziak, Thornton & Barahal, 2018). The Static-99R contains 10 static (i.e., unchangeable) items (e.g., prior sex offences) and the total score (-3 to 12) is used to estimate the likelihood of sexual offending. The Static-2002R was developed to improve the conceptual coherence of the Static-99R scale and, thus, to measure psychological constructs (e.g., deviant sexual interests, general criminality). Static-2002R also contains only static items (8 of 14 items from Static-99R), and the total score (-2 to 13) is used to estimate the likelihood of sexual offending. Also, the Static-2002R items are categorized into five conceptually meaningful constructs (see Hanson & Thornton, 2003).

A recent study found that considering the items from both Static-99R and Static-2002R improves the assessment of the psychologically meaningful constructs associated with sexual recidivism (Brouillette-Alarie, Babchishin, Hanson, & Helmus, 2016). The three major propensities are the following: 1) persistence/paraphilia (e.g., rate of sexual offending, male victim); 2) youthful stranger aggression (e.g., age at release, non-sexual violence at index, unrelated victim); and 3) general criminality (e.g., breach of conditional release; prior nonsexual violence; Brouillette-Alarie et al., 2016). The first construct, persistence/paraphilia, is associated with deviant sexual interests, but without the intent to harm their victims (e.g., pedophilia, voyeurism, and exhibitionism). The second construct, youthful stranger aggression, is related to the intent to sexually harm the victim (e.g., sexual sadism, hostility towards women). The construct of general criminality is related to the antisocial traits (e.g., impulsivity, lack of remorse, rule violations; Brouillette-Alarie, Proulx, & Hanson, 2017).

Furthermore, the Static-99R and Static-2002R recently adopted the standardized risk category system (i.e., Level I, II, III, IVa, and IVb; Hanson, Babchishin, Helmus, Thornton, & Phenix, 2016). Each category demonstrates quantitative information (e.g., likelihood of sexual reoffending, percentile ranks) as well as psychological characteristics associated with each level (e.g., sexual deviance and general antisociality). Consequently, the standardized risk levels assist evaluators to arrive at the same inferences for individuals assigned to the same risk category, regardless of the risk tool used.

There is only one study to examine the predictive validity (discrimination) of the Static-99R and Static-2002R for Indigenous peoples in Canada. Babchishin and colleagues (2012) examined the predictive validity of both scales among 1,588 individuals with a history of sexual crime (Indigenous, n = 319; non-Indigenous, n = 1,269). Overall, there was moderate discrimination between recidivists and non-recidivists for both groups for the Static-99/R (sexual recidivism; AUCs of .71 for Indigenous individuals and .74 for non-Indigenous individuals). The Static-2002R, however, was significantly less predictive of sexual recidivism for Indigenous individuals compared to non-Indigenous individuals. Total Static-2002R scores did not significantly predict sexual recidivism for Indigenous individuals with a history of sexual crime (AUC of .61 vs. AUC of .76 for non-Indigenous individuals). This study did not evaluate the calibration of either Static-99/R or Static-2002R.

Current Study

The Ewert decision (2018) highlighted the lack of research examining cultural bias in several widely adopted risk assessment scales in Canadian corrections - including the Static-99R. The purpose of this study was to provide an updated examination of the predictive validity of both the Static-99R and Static-2002R for Indigenous men and White men with a history of sexual crimes. The development and validation samples of Static-99R and Static-2002R comprised predominantly White individuals. White individuals - a dominant and privileged group - might have distinctive features associated with criminal behaviour, features that differ from the factors motivating criminal behaviour among Indigenous peoples.

There are other ethnic groups in Canada with potentially distinctive features (e.g., South Asians, East Asians, Caribbean Blacks). Of these groups, this study focused on Indigenous peoples because of their overrepresentation at all stages of the criminal justice system, and the concern that risk assessment practices could be contributing to this problem. Given legal and public policy concerns, this study also focused on the ability of these risk tools to identify individuals at high risk for sexual recidivism. Finally, this is the first study to assess both discrimination and calibration when evaluating the predictive accuracy of these specific tools.

Based on existing research, we expected Indigenous individuals to score higher on the total scores for both the Static-99R and Static-2002R, largely due to elevated scores on the items indicative of general antisociality. We also expected Indigenous peoples to score lower than White individuals on items related to sexual deviancy. Regarding predictive validity, we expected the Static-99R to show moderate discrimination for Indigenous individuals, but that discrimination would be lower than that observed for White individuals. Given the similarity between the Static-99R and Static-2002R, we expected similar results for both risk tools. Although previous studies with Indigenous peoples found that the Static-2002R was less accurate than the Static-99R, this finding lacks theoretical explanation and may be a sampling anomaly that could disappear with future research. No hypotheses regarding the calibration analyses were made for either instrument because no previous studies examined calibration of either tool for Indigenous peoples.

The second goal of this study was to examine the presence and predictive validity of risk-relevant characteristics for Indigenous and White peoples with a history of sexual crimes. Although no study to date has applied these specific constructs to Indigenous peoples, we would again expect that Indigenous individuals with a history of sexual crime to score higher on indicators of general criminality and lower on indicators of sexual deviancy than White individuals with a history of sexual crime.

Methods

Sample

The current study included two groups, adult Indigenous men (n = 653) and adult White men (n = 1,560) from five independent Canadian samples (Bonta & Yessine, 2005; Brankley, Lee, Babchishin, Hanson, & Harris, 2017; Haag, 2005; Lee, Mularczyk, Babchishin, Blais, & Bonta, 2018; Olver et al., 2018). The Indigenous study group represented a mixed group of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit individualsNote2 and the White study group referred to the individuals of European descent.

All samples were adult males (18 years or older) who had been convicted of sexual crimes and were classified by an administrative process as having a high level of risk and/or need (e.g., preselected [referred to as National Flagging System], detained until the end of a sentence, or attended high-intensity treatment programs). Although the samples were collected across all Canadian regions, most of the Indigenous group were from the Prairies (see Appendix A). The high proportion of Indigenous samples from the Prairies could be due to the even higher overrepresentation rates of Indigenous peoples in the Prairie provinces compared to other provinces (Department of Justice, 2017). The current samples partially overlap with the samples from Babchishin, Blais, et al. (2012; i.e., Bonta & Yessine [2005] and Haag [2005]).

Bonta & Yessine (2005). The original sample included three subgroups: (1) individuals flagged as potential Dangerous Offenders (considered for indeterminate sentences) by the National Flagging System, (2) individuals designated as Dangerous Offenders, and (3) individuals who committed a violent reoffence after being detained until their Warrant Expiry Date (WED). Only the first group (referred to as National Flagging System) was included in this study because Static-99 scores were only available for this group. These individuals were released into the community between 1992 and 2004 and followed until April 2005. Sexual recidivism was defined as a conviction for a sexual offence (excluding prostitution offences, indecent phone calls, and possession of child pornography) after the release into the community. The sexual recidivism information was obtained from the Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC).

Haag (2005). The original study sample included all male Canadian federal inmates serving a sentence for a sex offence whose warrant expiry date (WED) was in 1995. For the current study, only individuals detained until WED and released into the community (about 25% of the total sample) were included. Sexual recidivism was defined as a conviction for a further sexual offence within seven years after release, and the sexual recidivism information was obtained from the CPIC.

Olver et al. (2018). This study included adult males who served federal sentences and attended sex crime specific treatment programs (e.g., Clearwater programs, National Sex Offender Program) between 1983 and 2008. Sexual recidivism was defined as any criminal code violation for a sexually motivated offence (including child pornography offences). The recidivism information was obtained from the CPIC.

Brankley et al. (2017). This study was an extended follow-up to the Hanson and Harris (1998/2000) study. Adult males who had served part of their sentences in the community (e.g., probation, parole) were selected from all Canadian federal and provincial correctional systems (except Prince Edward Island). All individuals had been convicted of a sexual offence involving physical contact with the victim(s). Sexual recidivism was defined as any subsequent offences that were considered sexually motivated (including offence, charge, or conviction) and their recidivism information was obtained from official (CPIC) and unofficial sources (news articles).

Lee et al. (2018). The sample used in this study comprised individuals who had a history of sexual crimes taken from the Blais and Bonta (2015) study. Updated recidivism information was obtained resulting in a longer follow-up period than was available in the original study. Participants were adult males categorized into three separate and mutually exclusive groups: 1) Flagged Offenders, 2) Dangerous Offenders, and 3) Long-Term Offenders. File information for all three groups was gathered from the National Flagging System coordinators across Canada. Sexual recidivism was defined as any subsequent offences that were considered sexually motivated (including offence, charge, or conviction) and their recidivism information was obtained from official (CPIC) and unofficial sources (news articles).

In accordance with the Tri-Council Policy Statement 2 (TCPS2, Article 9.17, 2010), experts' reviews and opinions from individuals of Indigenous heritage who were engaged professionally with the issue of Indigenous overrepresentation in Canada's criminal justice system were solicited (Leticia Gutierrez and Patti McDonald). Their contributions help shape the interpretations and narratives of the research findings. This research project received research ethics approval from Carleton University's Research Ethics Boards (CUREB)-B.

Measures

Static-99R (Hanson & Thornton, 2000; Helmus, Thornton, et al., 2012). Static-99R is a 10-item empirical actuarial risk tool designed to assess the risk of sexual recidivism among adult males with a history of sexual offending. The Static-99R is identical to the Static-99 except that it contains revised age weights. The total score (ranging from -3 to 12) is calculated by summing all items and can be used to place individuals in one of five risk categories: Level I - very low risk (scores of -3 to -2), Level II - below average risk (scores of -1 to 0), Level III - average risk (scores of 1 to 3), Level IVa - above average risk (scores of 4 to 5), and Level IVb - well above average risk (scores of 6 or higher; Hanson et al., 2017). When necessary, Static-99R scores were computed from Static-99 scores by using the individual's date of birth to calculate the updated age item.

Static-2002R (Hanson & Thornton, 2003; Helmus, Thornton, et al., 2012). The Static-2002R is also an empirical actuarial risk assessment tool for an adult male with a history of sexual offending. The scale has 14 items grouped into five main subscales: Age at Release (1 item), Persistence of Sex Offending (3 items), Sexual Deviance (3 items), Relationship to Victims (2 items), and General Criminality (5 items). The Static-2002R items are identical to the original Static-2002 except for updated age weights. The total score for Static-2002R can range from -2 to 13 and can be used to place individuals in one of five risk categories: Level I - very low risk (scores of -2 to -1), Level II - below average risk (scores of 0 to 1), Level III - average risk (scores of 2 to 4), Level IVa - above average risk (scores of 5 to 6), and Level IVb - well above average risk (scores of 7 or higher; Hanson et al., 2017). When necessary, Static-2002R scores were computed from Static-2002 scores by using the individual's date of birth to calculate the updated age item.

Sexual recidivism. Sexual recidivism was defined as any subsequent offence(s) that were considered sexually motivated (offence, charge or conviction). Some studies, however, did not consider Category B sex offencesNote3 as defined by the Static-99R coding rules (e.g., possession of child pornography, prostitution offenses; Phenix, Fernandez, Harris, Helmus, Hanson, & Thornton, 2017, p. 27). To assess sexual recidivism, official criminal records were used for all of the studies (e.g., CPIC) and unofficial sources were used for a subset of the studies (e.g., news articles).

Psychological constructs of Static-99/R and Static-2002R. Three psychological constructs were identified from the Static-99R and Static-2002R items: 1) persistence/paraphilia, related to deviant sexual interests but without the intent to harm their victims (e.g., pedophilia, voyeurism, and exhibitionism), 2) youthful stranger aggression, related to the intent to sexually harm the victim (e.g., sexual sadism, hostility towards women), and 3) general criminality, related to the antisocial trait (e.g., impulsivity, lack of remorse, rule violations; Brouillette-Alarie et al., 2016; Brouillette-Alarie et al., 2017). These psychological constructs were used to compare risk-relevant characteristics between Indigenous and White individuals who had committed sexual crimes.

Plan of Analysis

Aggregation of findings. AUC values and logistic regression parameters across the studies were aggregated using fixed-effect meta-analyses (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009; Hanson & Broom, 2005). Fixed-effect analyses have the advantage of providing an estimate of between-study variability (Q) that can be used to compare the variability across the studies (Borenstein et al., 2009). The Q statistics is distributed as a chi-square, with k-1 degree of freedom (k = the number of studies).

Comparing the risk-relevant characteristics. For assessing the relationship of risk-relevant characteristics between Indigenous and White study groups, AUC analyses (Swets, Dawes, & Monahan, 2000) were used. The AUC can vary between 0 and 1, with .50 indicating no difference between the groups. AUCs above .50 indicate that the Indigenous study group has higher levels of the risk-relevant characteristic compared to the White study group. As a rough heuristic, an AUC of .56 corresponds to small effect size, while .64 reflects a moderate effect, and .71 reflects a large effect size (Rice & Harris, 2005). In contrast, AUCs below .50 indicate that the White study group has higher levels of the risk relevant characteristic compared to the Indigenous study group (.44 for a small effect, .33 for a moderate effect, and .29 for a large effect). An AUC value is statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval does not include .50.

When a risk factor was a binary variable, the odds ratio (instead of AUC) was calculated with 0.5 added to each cell to stabilize the variance (Fleiss & Berlin, 2009). An odds ratio is defined as p/(1-p), where p is the raw proportion of the sample with the characteristic. Odds ratios above 1 indicate that the Indigenous study group has higher levels of the risk-relevant characteristic compared to the White study group. For example, an odds ratio of 2 would indicate that the Indigenous study group has twice the odds of having the risk-relevant characteristic compared to the White study group. No association is indicated when the 95% confidence interval of the odds ratio contains 1 (i.e., the odds are equal for both groups).

Predictive validity of Static-99R and Static-2002R. Assessing the predictive accuracy of a risk assessment instrument requires considering discrimination (how different are recidivists from non-recidivists?) as well as calibration (correspondence between expected and observed recidivism rates). For discrimination, we used two statistical methods: 1) AUCs from receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis (Swets et al., 2000), and 2) odds ratios from logistic regression (Hosmer, Lemeshow, & Sturdivant, 2013). For calibration, we used a fixed-effect meta-analysis to compare logistic regression parameters (i.e., base rates; Borenstein et al., 2009; Hanson & Broom, 2005).

Area Under the Curve (AUC). AUC values can also be interpreted as the probability that a randomly selected recidivist would have a more deviant score than a randomly selected non-recidivist. AUC values are expected to be smaller in prognostic studies than in diagnostic studies because the outcome of interest in prognostic studies does not exist at the time of assessment, and may never happen (Royston, Moons, Altman, & Vergouwe, 2009; Helmus & Babchishin, 2017). The AUC has the advantage of being insensitive to base rates and robust to outliers (Ruscio, 2008). An AUC value is statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval does not include .50.

To compare the unpaired AUC values, bootstrapping (n = 10,000) was used to obtain the standard error (S.E.) of the differences between AUC1 and AUC2 of the two (original) ROC curves with a pROC packagefor the statistical software R (Robin et al., 2011, 2014). The 95% confidence intervals of differences between AUC1 and AUC2 were calculated as follows:

95% C.I. = (AUC1 – AUC2) ± 1.96* S.E.

The difference of AUC values is statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval does not include 0.

Odds ratios. Odds ratios indicate the change in relative risk associated with a one-unit change in Static-99/R and Static-2002R scores. For example, Static-99R scores for the 5-year estimates are associated with a consistent relative risk increase of approximately 1.28 (Hanson, Thornton, Helmus, & Babchishin, 2016) in the high-risk/high-needs samples. This indicates that the odds of recidivism increase 1.28 times as each Static-99R score increases. The primary advantage of odds ratios is that they are less influenced by a restriction of range than AUCs (Hanson, 2008).

Comparing logistic regression parameters. Calibration was examined by comparing the extent to which logistic regression parameters, such as intercept values (centered on Static-99R scores of 2 [B02] and Static-2002R scores of 3[B03]), differed from the logistic regression parameters for the high-risk/high-needs sample norms (Hanson et al., 2016). B0 coefficients centered on 2 for the Static-99R and centered on 3 for the Static-2002R (median values among those with a sexual offence conviction in Canada) represent the expected recidivism rate for sex offenders in the middle of the risk distribution. Specifically, the B02 represents the expected recidivism rate for a Static-99R score of 2 (p2) in logit units (ln[p2/{1-p2}]) and the B03 represents the expected recidivism rate for a Static-2002R score of 3 (p3) in logit units (ln[p3/{1-p3}]).

In addition, high-risk/high-needs sample norms were used to evaluate the calibration of the Static-99R and Static-2002R given that the current samples were preselected as individuals with a high risk to reoffend (e.g., individuals flagged as potential Dangerous Offenders or who had attended high-intensity treatment). Differences between the parameters in the current sample and those of the norms were tested using Q statistics from a fixed-effect meta-analysis (Borenstein et al., 2009; Hanson & Broom, 2005). The Q statistics is distributed as a chi-square, with k-1 degree of freedom (k = the number of studies, which in this case k = 2: Indigenous study group versus the norms, and, separately, the White study group versus the norms).

The index used to assess the differences between the parameters of Indigenous and White study groups was the bi-difference statistic, which was calculated for each parameter by subtracting the bi of the White samples from bi of the Indigenous samples. The variance for the bi difference was calculated according to the Ley (1972) using the following formula:

Var (bi diff) = s2x + s2y - 2rxysxsy

where sx is the standard deviation of the di from the Indigenous sample, sy is the standard deviation of the di from the White sample, and rxy is the correlation coefficient estimating the relationship between the average effect size for the Indigenous sample and the White sample.

Results

The Indigenous study group was, on average, approximately 4 years younger than the White study group (36.1 versus 40.6 years; AUC = .61, 95% CI [.57, .65]). The average Static-99R and Static-2002R total scores for both groups were in the Above Average range (Risk Level IVa, see Table 1), and were approximately a 1/2 point higher for the Indigenous study group than the White study group (4.8 versus 4.3 for Static-99R, AUC = .57, 95% CI [.53, .60]; 6.1 versus 5.7 for Static-2002R, AUC = .55, 95% CI [.51, .59]).

Indigenous |

White |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Study |

n |

Age at release |

Static-99R |

Static-2002R |

n |

Age at release |

Static-99R |

Static-2002R |

|

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

||||

Bonta & Yessine (2005) |

37 |

36.8 (7.8) |

5.1 (2.1) |

- |

118 |

40.4 (10.1) |

5.0 (2.2) |

- |

|

Haag (2005) |

50 |

33.7 (8.7) |

4.2 (1.9) |

5.8 (1.9) |

141 |

38.6 (10.1) |

3.9 (2.4) |

5.5 (2.5) |

|

Olver et al. (2018) |

425 |

- |

4.6 (2.4) |

- |

739 |

- |

3.2 (2.9) |

- |

|

Brankley et al. (2017) |

36 |

35.5 (8.4) |

4.7 (2.0) |

6.3 (2.1) |

346 |

40.4 (11.6) |

4.2 (2.4) |

5.9 (2.5) |

|

Lee et al. (2018) |

105 |

38.3 (9.2) |

5.4 (2.1) |

6.4 (2.1) |

216 |

43.9 (12.3) |

4.8 (2.7) |

5.8 (2.8) |

|

Average (fixed-effect) |

653 |

36.1 (4.2) |

4.8 (0.9) |

6.1 (1.2) |

1,560 |

40.6 (5.5) |

4.3 (1.1) |

5.7 (1.5) |

|

Comparing Risk-Relevant Characteristics

The Indigenous study group showed less persistence/paraphilia than the White study group (AUC = .39). Compared to the White study group, the Indigenous study group was significantly less likely to have a history of non-contact sex offences (odds ratio = 0.45), male victim (odds ratio = 0.22), unrelated young victim (odds ratio = 0.27), and prior sex offences (AUC = 0.45; Table 2).

Regarding youthful stranger aggression, the Indigenous study group showed a significantly higher score than the White study group (AUC of .60). The difference was attributed to two items (age at release and index non-sexual violence). Specifically, the Indigenous study group was significantly younger than the White study group (AUC of .59) and more likely to have been convicted of a violent index offence (odds ratio = 1.61; Table 2).

Indigenous |

White |

Odds Ratio |

95% CI |

AUC |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Items |

% |

n/N |

% |

n/N |

|||||

Persistence/Paraphilia |

|||||||||

Prior sex offences (Static-99R; Item #5) |

.453 [.413, .493] |

||||||||

None |

36.0 |

82/228 |

34.7 |

285/821 |

|||||

1-2 charges or 1 conviction |

30.3 |

69/228 |

22.5 |

185/821 |

|||||

3-5 charges or 2-3 convictions |

21.9 |

50/228 |

19.5 |

160/821 |

|||||

6+ charges or 4+ convictions |

11.8 |

27/228 |

23.3 |

191/821 |

|||||

Prior sentencing occasions for sexual offences (Static-2002R; Item #2) |

.470 [.424, .515] |

||||||||

None |

36.0 |

82/191 |

38.8 |

273/703 |

|||||

1 |

26.8 |

61/191 |

32.7 |

230/703 |

|||||

2-3 |

18.4 |

42/191 |

20.5 |

144/703 |

|||||

4 or more |

2.6 |

6/191 |

8.0 |

56/703 |

|||||

Rate of sexual offending (Static-2002R; Item #4) |

1.04 |

[0.73, 1.48] |

|||||||

< 1 sentencing occasion every 15 years |

71.7 |

137/191 |

72.4 |

509/703 |

|||||

≥ 1 sentencing occasion every 15 years |

28.3 |

54/191 |

27.6 |

194/703 |

|||||

Non-contact sex offences (Static-99R; Item #7) |

0.45 |

[0.24, 0.82] |

|||||||

No |

94.7 |

215/227 |

88.6 |

727/821 |

|||||

Yes |

5.3 |

12/227 |

11.4 |

94/821 |

|||||

Male victim (Static-99R; Item #10) |

0.22 |

[0.15, 0.35] |

|||||||

No |

88.6 |

202/228 |

63.2 |

519/821 |

|||||

Yes |

11.4 |

26/228 |

36.8 |

302/821 |

|||||

2+ victims < 12 year-old, one unrelated (Static-2002R;Item # 7) |

0.27 |

[0.18, 0.40] |

|||||||

No |

82.7 |

158/191 |

56.2 |

395/703 |

|||||

Yes |

17.3 |

33/191 |

43.8 |

308/703 |

|||||

Persistence/Paraphilia |

M = 1.48 (SD = 1.53), n = 191 |

M = 2.18 (SD = 1.81), n = 703 |

.387 [.343, .430] |

||||||

Youthful stranger aggression |

|||||||||

Age at release (Static-99R; Item #1) |

.590 [.549, .631] |

||||||||

18 to 34.9 |

46.6 |

103/221 |

33.3 |

263/789 |

|||||

35 to 39.9 |

18.6 |

41/221 |

18.0 |

142/789 |

|||||

40 to 59.9 |

33.9 |

75/221 |

41.7 |

329/789 |

|||||

60 or older |

0.9 |

2/221 |

7.0 |

55/789 |

|||||

Juvenile sexual arrest prior to age 18 (Static-2002R; Item #3) |

1.01 |

[0.56, 1.81] |

|||||||

No |

92.1 |

176/191 |

92.0 |

647/703 |

|||||

Yes |

7.9 |

15/191 |

8.0 |

56/703 |

|||||

Ever lived with a lover for +2 years (Static-99R; Item #2) |

1.23 |

[0.91, 1.66] |

|||||||

Yes |

57.7 |

131/227 |

62.7 |

510/814 |

|||||

No |

42.3 |

96/227 |

37.3 |

304/814 |

|||||

Index non-sexual violence - any convictions (Static-99R; Item #3) |

1.61 |

[1.18, 2.19] |

|||||||

No |

63.0 |

143/227 |

73.2 |

601/821 |

|||||

Yes |

37.0 |

84/227 |

26.8 |

220/821 |

|||||

Unrelated victim (Static-99R; Item #8) |

0.73 |

[0.47, 1.13] |

|||||||

No |

13.6 |

31/228 |

10.4 |

85/821 |

|||||

Yes |

86.4 |

197/228 |

89.6 |

736/821 |

|||||

Stranger victim (Static-99R; Item #9) |

1.21 |

[0.90, 1.62] |

|||||||

No |

50.4 |

115/228 |

55.1 |

452/820 |

|||||

Yes |

49.6 |

113/228 |

44.9 |

368/820 |

|||||

Youthful stranger aggression |

M = 3.26 (SD = 1.62), n = 184 |

M = 2.68 (SD = 1.77), n = 668 |

.599 [.553, .644] |

||||||

General Criminality |

|||||||||

Any community supervision violation (Static-2002R; Item #12) |

3.88 |

[2.36, 6.36] |

|||||||

No |

9.9 |

19/191 |

30.4 |

214/703 |

|||||

Yes |

90.1 |

172/191 |

69.6 |

489/703 |

|||||

Years free prior to index sex offence (Static-2002R; Item #13) |

3.11 |

[2.05, 4.72] |

|||||||

> 36 months prior to sexual offence AND > 48 months prior to sex conviction |

15.7 |

30/191 |

37.0 |

260/703 |

|||||

< 36 months prior to sexual offence OR < 48 months prior to sex conviction |

84.3 |

161/191 |

63.0 |

443/703 |

|||||

Prior criminal involvement (Static-2002R; Item #10) |

2.58 |

[1.37, 4.86] |

|||||||

No |

5.8 |

11/191 |

14.1 |

99/703 |

|||||

Yes |

94.2 |

180/191 |

85.9 |

604/703 |

|||||

Prior sentencing occasions for anything (Static-2002R; Item #11) |

.670 [.628, .712] |

||||||||

0-2 |

14.7 |

28/191 |

42.5 |

299/703 |

|||||

3-13 |

64.9 |

124/191 |

50.9 |

358/703 |

|||||

14 + |

20.4 |

39/191 |

6.5 |

46/703 |

|||||

Prior sentencing dates (Static-99R; Item #6) |

3.17 |

[2.28, 4.41] |

|||||||

3 or less |

24.6 |

56/228 |

50.9 |

418/821 |

|||||

4 or more |

75.4 |

172/228 |

49.1 |

403/821 |

|||||

Prior non-sexual violence – any convictions (Static-99R; Item #4) |

3.25 |

[2.36, 4.47] |

|||||||

No |

27.6 |

63/228 |

55.5 |

455/820 |

|||||

Yes |

72.4 |

165/228 |

44.5 |

365/820 |

|||||

Prior non-sexual violence sentencing occasion (Static-2002R; Item #14) |

3.96 |

[2.79, 5.61] |

|||||||

No |

27.7 |

53/191 |

60.5 |

425/703 |

|||||

Yes |

72.3 |

138/191 |

39.5 |

278/703 |

|||||

General Criminality |

M = 4.47 (SD = 1.43), n = 191 |

M = 3.22 (SD = 1.74), n = 703 |

.722 [.682, .763] |

||||||

Note: Numbers in bold indicate statistical significance (i.e., p < 0.05). |

|||||||||

The Indigenous study group showed more general criminality than the White study group (AUC = .72; Table 2). All the items associated with general criminality were significantly higher for the Indigenous study group than the White study group. Compared to the White study group, the Indigenous study group was more likely to have a history of community supervision violation, prior non-sexual violent crimes, and prior criminal involvement.

Predictive Accuracy of Three Psychological Structures and Items

Persistence/paraphilia predicted sexual recidivism for the White study group (AUC of .65). The AUC value for the Indigenous study group was, however, lower than that of the White study group (AUC of .58), but the difference was not statistically significant. All the items of persistence/paraphilia had lower predictive accuracy for the Indigenous study group compared the White study group. Only two items (prior sex offences and unrelated young victim) significantly predicted sexual recidivism rates for the Indigenous study group. For one item (non-contact sex offences), the direction of the effect was reversed for the Indigenous study group (i.e., Indigenous peoples with a history of non-contact sex offences are less likely to commit another sexual crime in the future; Table 3).

Indigenous |

White |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Items |

AUC |

n/N |

AUC |

n/N |

Diff. |

95% C.I. |

|||

Persistence/Paraphilia |

|||||||||

Prior sex offences (Static-99R; Item #5) |

.608 [.528, .688] |

59/219 |

.626 [.582, .670] |

187/759 |

- .018 |

[-.108, .072] |

|||

Prior sentencing occasions for sexual offences (Static-2002R; Item #2) |

.571 [.482, .660] |

50/182 |

.628 [.582, .674] |

171/641 |

- .057 |

[-.159, .045] |

|||

Rate of sexual offending (Static-2002R; Item #4) |

.573 [.496, .650] |

50/182 |

.606 [.564, .647] |

171/641 |

- .033 |

[-.120, .054] |

|||

Non-contact sex offences (Static-99R; Item #7) |

.474 [.448, .499] |

59/219 |

.522 [.494, .551] |

187/759 |

- .048 |

[-.086, -.010] |

|||

Male victim (Static-99R; Item #10) |

.495 [.449, .541] |

59/219 |

.538 [.498, .579] |

187/759 |

- .043 |

[-.103, .017] |

|||

2+ victims < 12 year-old, one unrelated (Static-2002R;Item # 7) |

.572 [.502, .641] |

50/182 |

.573 [.530. .617] |

171/641 |

- .001 |

[-.050, .048] |

|||

Persistence/Paraphilia |

.581 [.489, .673] |

50/182 |

.645 [.597, .693] |

171/641 |

- .127 |

[-.333, .079] |

|||

Youthful stranger aggression |

|||||||||

Age at release (Static-99R; Item #1) |

.514 [.436, .592] |

59/219 |

.616 [.574, .659] |

186/757 |

- .102 |

[-.189, -.015] |

|||

Juvenile sexual arrest prior to age 18 (Static-2002R; Item #3) |

.502 [.458, .546] |

50/182 |

.534 [.507, .561] |

171/641 |

-.032 |

[-.084, .020] |

|||

Ever lived with a lover for +2 years (Static-99R; Item #2) |

.470 [.396, .543] |

59/218 |

.531 [.490, .571] |

186/753 |

- .061 |

[-.143, .021] |

|||

Index non-sexual violence - any convictions (Static-99R; Item #3) |

.580 [.506, .654] |

59/218 |

.512 [.476, .549] |

187/759 |

.068 |

[-.013, .149] |

|||

Unrelated victim (Static-99R; Item #8) |

.516 [.466, .566] |

59/219 |

.537 [.516, .558] |

187/759 |

- .021 |

[-.074, .032] |

|||

Stranger victim (Static-99R; Item #9) |

.513 [.438, .588] |

59/219 |

.577 [.536, .618] |

187/758 |

- .064 |

[-.148, .020] |

|||

Youthful stranger aggression |

.529 [.439, .620] |

50/182 |

.644 [.597, .690] |

170/636 |

- .115 |

[-.217, -.013] |

|||

General Criminality |

|||||||||

Any community supervision violation (Static-2002R; Item #12) |

.572 [.542, .602] |

50/182 |

.616 [.582, .649] |

171/641 |

- .044 |

[-.089, .001] |

|||

Years free prior to index sex offence (Static-2002R; Item #13) |

.517 [.459, .576] |

50/182 |

.579 [.539, .619] |

171/641 |

- .062 |

[-.133, .009] |

|||

Prior criminal involvement (Static-2002R; Item #10) |

.500 [.461, .539] |

50/182 |

.548 [.522, .573] |

171/641 |

- .048 |

[-.095, -.001] |

|||

Prior sentencing occasions for anything (Static-2002R; Item #11) |

.578 [.499, .578] |

50/182 |

.592 [.549, .635] |

171/641 |

- .014 |

[-.105, .077] |

|||

Prior sentencing dates (Static-99R; Item #6) |

.568 [.509, .626] |

59/219 |

.566 [.525, .607] |

187/759 |

.002 |

[-.096, .100] |

|||

Prior non-sexual violence – any convictions (Static-99R; Item #4) |

.563 [.501, .625] |

59/219 |

.541 [.500, .583] |

187/758 |

.022 |

[-.051, .095] |

|||

Prior non-sexual violence sentencing occasion (Static-2002R; Item #14) |

.545 [.475, .616] |

50/182 |

.515 [.472, .558] |

171/641 |

.030 |

[-.051, .111] |

|||

General Criminality |

.589 [.501, .677] |

50/182 |

.613 [.568, .658] |

171/641 |

-.024 |

[-.122, .074] |

|||

Note: Numbers in bold indicate statistical significance (i.e., p < 0.05). |

|||||||||

Youthful stranger aggression predicted sexual recidivism for the White study group (AUC of .64), but not for the Indigenous study group (AUC of .53), which was significantly lower than that of the White study group. Specifically, the item of age at release for the Indigenous study group did not predict sexual recidivism and was significantly lower than the value for the White study group (AUCs of .51 versus .62). In other words, sexual recidivism risk for the Indigenous study group was unrelated to age at release. In addition, it was found that the relationship between the Indigenous study group and their victims (i.e., unrelated/stranger victim) was not associated with sexual recidivism risk. Only one item (index non-sexual violence) predicted sexual recidivism for the Indigenous study group (AUC of .58) whereas it did not predict for the White study group (AUC of .51). The difference was, however, not statistically significant (Table 3).

Overall, general criminality significantly and similarly predicted sexual recidivism for both Indigenous and White study groups (AUC of .59 and .61). The item of prior criminal involvement did not predict sexual recidivism for the Indigenous study group (AUC of .50), and it was also significantly lower than that of the White study group (AUC of .55; Table 3). Most AUC values between Indigenous and White study groups, however, did not differ significantly.

Predictive Validity Static-99R and Static-2002R

Overall, sexual recidivism rates for the Indigenous study group were higher than those of White study group (Table 4). For the Indigenous study group, 16.2% sexually reoffended within a fixed 5-year follow-up period and 24.0% sexually reoffended within a fixed 10-year follow-up period. For the White study group, 11.9% sexually reoffended within a fixed 5-year follow-up period and 19.3% sexually reoffended within a fixed 10-year follow-up period.

Indigenous |

White |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Study |

Sexual Recidivism |

AUC |

Sexual Recidivism |

AUC |

|||||

% |

n/N |

% |

n/N |

||||||

Fixed 5-year |

|||||||||

Bonta & Yessine (2005) |

19.2 |

5/26 |

.60 [.25, .96] |

14.4 |

13/90 |

.71 [.58, .85] |

|||

Haag (2005) |

28.0 |

14/50 |

.60 [.42, .77] |

17.7 |

25/141 |

.70 [.59, .81] |

|||

Olver et al. (2018) |

14.3 |

57/400 |

.62 [.55, .70] |

9.6 |

64/665 |

.71 [.65, .77] |

|||

Brankley et al. (2017) |

11.4 |

4/35 |

.62 [.27, .97] |

11.4 |

35/308 |

.70 [.61, .80] |

|||

Lee et al. (2018) |

19.3 |

17/88 |

.56 [.41, .72] |

15.8 |

27/171 |

.69 [.59, .79] |

|||

Average (fixed-effect) |

16.2 |

97/599 |

.61 [.55, .67]ns |

11.9 |

164/1,375 |

.70 [.66, .74] ns |

|||

Fixed 10-year |

|||||||||

Olver et al. (2018) |

23.4 |

64/274 |

.67 [.59, .74] |

16.7 |

72/432 |

.71 [.65, .77] |

|||

Brankley et al. (2017) |

20.0 |

7/35 |

.60 [.34, .87] |

21.7 |

65/299 |

.74 [.67, .80] |

|||

Lee et al. (2018) |

28.8 |

19/66 |

.66 [.51, .81] |

23.1 |

27/117 |

.70 [.59, .82] |

|||

Average (fixed-effect) |

24.0 |

90/375 |

.66 [.60, .72] ns |

19.3 |

164/848 |

.72 [.68, .76] ns |

|||

Note: ns indicates no significant variability across studies (Q statistics). Numbers in bold indicate statistical significance (i.e., p < 0.05). |

|||||||||

Static-99R

Discrimination. Using the fixed 5-year follow-up, the Static-99R was able to discriminate recidivists from non-recidivists for both Indigenous and White study groups. Whereas the White study group had the moderate AUC value of .70, the AUC value for the Indigenous study group was smaller (AUC = .61). With the fixed 10-year follow-up, the AUC value of the Indigenous study group increased to moderate effect size (AUC of .66) but was still lower than the AUC value of the White study group (AUC of .72; Table 4).

Before comparing predictive accuracies across groups, the degree of consistency within each group was examined. For the Indigenous study group, both the 5-year (5 studies) and 10-year sexual recidivism rates (3 studies) with a Static-99R score of 2 (B02) were very similar across the studies included in this meta-analysis (both p > .50, see Table 5). The relative risk (B1) of the Static-99R across the studies was also very similar with a fixed 5-year follow-up (5 studies) as well as with a fixed 10-year follow-up (3 studies; both p > .70, see Table 5).

Study |

Base rate (Static-99R score of 2 in logit units) |

Relative risk |

Odds Ratio |

95% C.I. |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

B02 |

SE |

B1 |

SE |

Lower |

Upper |

||||

Fixed 5-year |

|||||||||

Bonta & Yessine (2005) |

- 1.876 |

(13.3%) |

.954 |

.162 |

.234 |

1.18 |

0.72 |

1.63 |

|

Haag (2005) |

- 1.384 |

(20.0%) |

.551 |

.187 |

.181 |

1.21 |

0.85 |

1.56 |

|

Olver et al. (2018) |

- 2.393 |

(8.4%) |

.265 |

.201 |

.067 |

1.22 |

1.09 |

1.35 |

|

Brankley et al. (2017) |

- 2.366 |

(8.6%) |

.991 |

.114 |

.283 |

1.12 |

0.57 |

1.68 |

|

Lee et al. (2018) |

- 2.030 |

(11.6%) |

.623 |

.168 |

.148 |

1.18 |

0.89 |

1.47 |

|

Q (df = 4) |

2.93, p = .570 |

0.14, p = .998 |

|||||||

I2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|||||||

Average (fixed-effect) |

- 2.175 |

(10.2%) |

.212 |

.190 |

.056 |

1.21 |

1.09 |

1.35 |

|

Fixed 10-year |

|||||||||

Olver et al. (2018) |

- 2.001 |

(11.9%) |

.276 |

.274 |

.071 |

1.32 |

1.18 |

1.45 |

|

Brankley et al. (2017) |

- 1.736 |

(15.0%) |

.783 |

.126 |

.226 |

1.13 |

0.69 |

1.58 |

|

Lee et al. (2018) |

- 2.195 |

(10.0%) |

.756 |

.342 |

.175 |

1.41 |

1.06 |

1.75 |

|

Q (df = 2) |

0.18, p = .914 |

0.58, p = .750 |

|||||||

I2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|||||||

Average (fixed-effect) |

- 1.995 |

(12.0%) |

.246 |

.271 |

.063 |

1.31 |

1.16 |

1.48 |

|

Note: Numbers in bold indicate statistical significance (i.e., p < 0.05). |

|||||||||

For the White study group, both the 5-year (5 studies) and 10-year sexual recidivism rates (3 studies) with a Static-99R score of 2 (B02) across the studies were very similar (both p > .60, see Table 6). The relative risk (B1) of Static-99R across the studies was also very similar with a fixed 5-year follow-up (5 studies; p = .93) as well as with a fixed 10-year follow-up (3 studies; p = .60; Table 6).

Study |

Base rate (Static-99R score of 2 in logit units) |

Relative risk |

Odds Ratio |

95% C.I. |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

B02 |

SE |

B1 |

SE |

Lower |

Upper |

||||||||

Fixed 5-year |

|||||||||||||

Bonta & Yessine (2005) |

- 3.305 |

(3.5%) |

.863 |

.442 |

.188 |

1.56 |

1.19 |

1.92 |

|||||

Haag (2005) |

- 2.343 |

(8.8%) |

.392 |

.324 |

.106 |

1.38 |

1.17 |

1.59 |

|||||

Olver et al. (2018) |

- 2.889 |

(5.3%) |

.212 |

.287 |

.054 |

1.33 |

1.23 |

1.44 |

|||||

Brankley et al. (2017) |

- 3.047 |

(4.5%) |

.366 |

.340 |

.089 |

1.40 |

1.23 |

1.58 |

|||||

Lee et al. (2018) |

- 2.539 |

(7.3%) |

.401 |

.279 |

.092 |

1.32 |

1.14 |

1.50 |

|||||

Q (df = 4) |

2.75, p = .600 |

0.90, p = .925 |

|||||||||||

I2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|||||||||||

Average (fixed-effect) |

- 2.797 |

(5.7%) |

.151 |

.306 |

.038 |

1.36 |

1.26 |

1.46 |

|||||

Fixed 10-year |

|||||||||||||

Olver et al. (2018) |

- 2.149 |

(10.4%) |

.228 |

.326 |

.059 |

1.38 |

1.27 |

1.50 |

|||||

Brankley et al. (2017) |

- 2.437 |

(8.0%) |

.292 |

.407 |

.075 |

1.50 |

1.36 |

1.65 |

|||||

Lee et al. (2018) |

- 2.070 |

(11.2%) |

.406 |

.300 |

.099 |

1.35 |

1.15 |

1.54 |

|||||

Q (df = 2) |

0.78, p = .677 |

1.02, p = .600 |

|||||||||||

I2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|||||||||||

Average (fixed-effect) |

- 2.227 |

(9.7%) |

.164 |

.346 |

.042 |

1.41 |

1.30 |

1.53 |

|||||

Note: Numbers in bold indicate statistical significance (i.e., p < 0.05). |

|||||||||||||

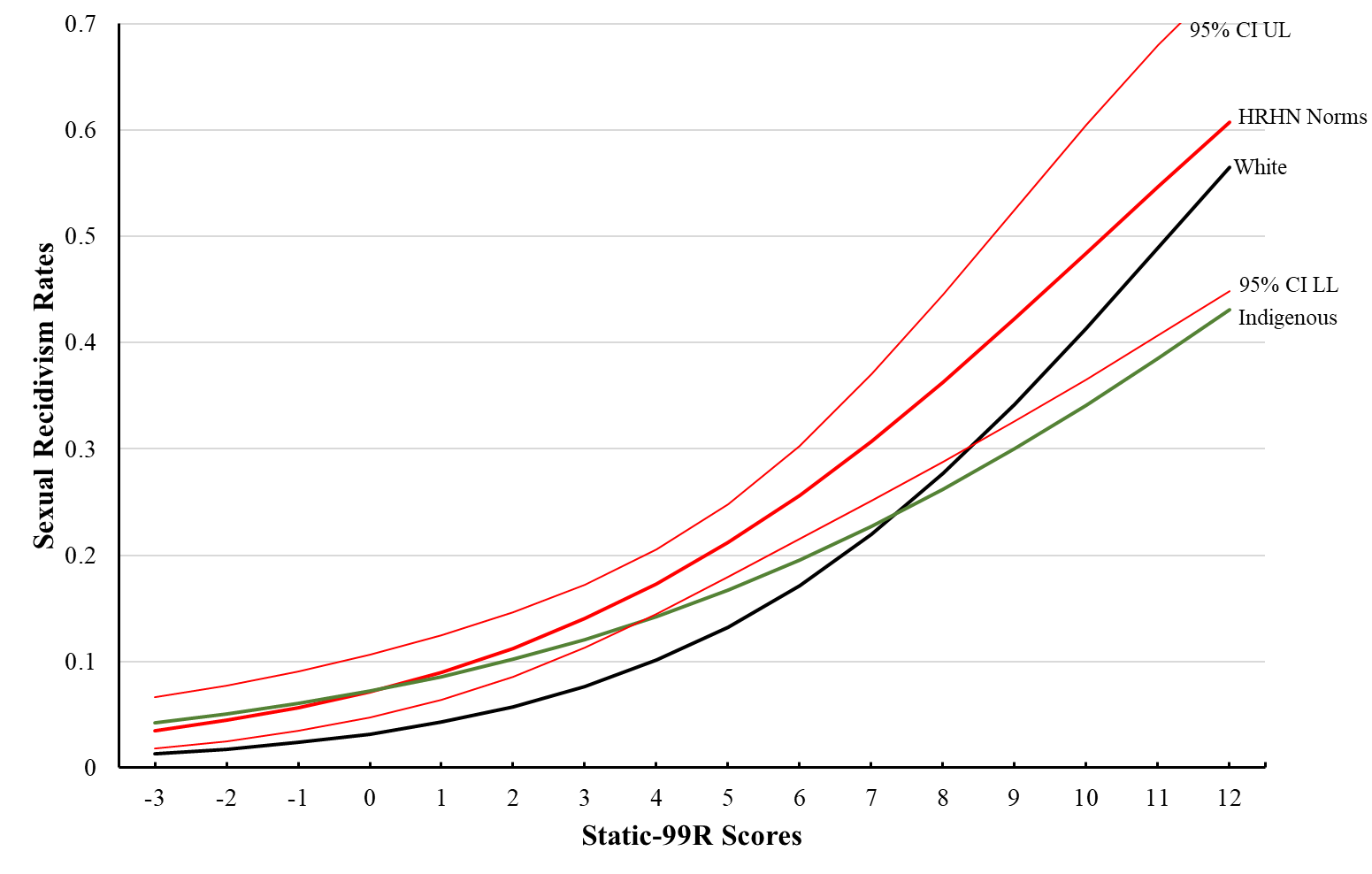

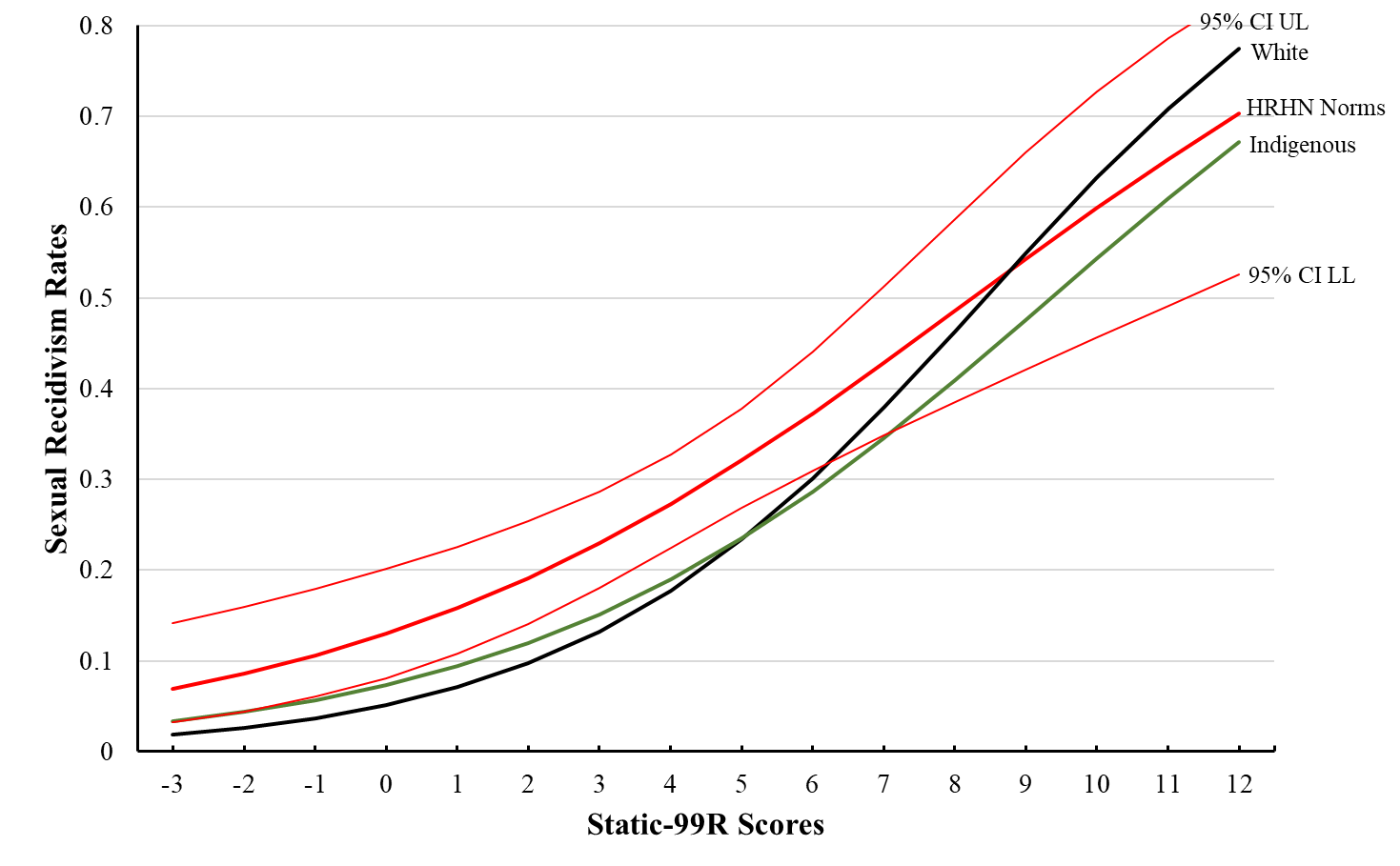

The 5-year sexual recidivism rates with a Static-99R score of 2 for the Indigenous study group were significantly higher than that of the White study group (10.2% versus 5.7%; Table 7; Figure 1). The 10-year sexual recidivism rates at a Static-99R score of 2 for the Indigenous study group were, however, similar to that of the White study group (11.9% versus 9.7%; Table 7; Figure 2). The discrimination (change in relative risk) was higher for the White study group than for the Indigenous study group with both 5-year (odds ratios = 1.21 versus 1.36) as well as 10-year follow-up periods (1.31 versus 1.41), but these differences in discrimination between racial groups were not statistically significant (Table 7; Figure 1; Figure 2).

Meta-Average (HRHN Norms) |

Indigenous |

White |

BIndigenous-White |

95% C.I. |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Fixed 5-year |

|||||||||

Base rate |

|||||||||

B02 (SD) |

- 2.06 (.153) (11.3%) |

- 2.18 (.212) (10.2%) |

- 2.80 (.151) (5.7%) |

0.623 |

[0.179, 1.066] |

||||

QΔ (df = 1) |

0.18 |

11.60*** |

|||||||

Relative risk |

|||||||||

B1 (SD) |

.250 (.042) |

.190 (.055) |

.306 (.038) |

- 0.116 |

[- 0.245, 0.013] |

||||

QΔ (df = 1) |

0.755 |

0.971 |

|||||||

Fixed 10-year |

|||||||||

Base rate |

|||||||||

B02 (SD) |

- 1.44 (.186) (19.2%) |

- 2.00 (.246) (11.9%) |

- 2.23 (.164) (9.7%) |

0.232 |

[- 0.307, 0.770] |

||||

QΔ (df = 1) |

3.64 |

9.99** |

|||||||

Relative risk |

|||||||||

B1 (SD) |

.231 (.056) |

.271 (.063) |

.346 (.042) |

- 0.075 |

[- 0.222, 0.071] |

||||

QΔ (df = 1) |

0.28 |

2.72 |

|||||||

Note: ***p < .001, **p < .01, * p < .05. r (between Indigenous and White) = 0.260 for B02 and 0.208 for B1. Numbers in bold indicate statistical significance (i.e., p < 0.05). |

|||||||||

Figure 1. Logistic curves of Static-99R for Indigenous and White study groups with the High Risk/High Need Norms with a fixed 5-year follow-up.

Image description

This figure illustrates the logistic curves of Static-99R for Indigenous and White study groups with the High Risk/High Need Norms with a fixed 5-year follow-up showing the 5-year sexual recidivism rates with a Static-99R score of 2 for the Indigenous study group were significantly higher than that of the White study group (10.2% versus 5.7%). The discrimination (change in relative risk) was higher for the White study group than for the Indigenous study group with both 5-year (odds ratios = 1.21 versus 1.36) as well as 10-year follow-up periods (1.31 versus 1.41), but these differences in discrimination between racial groups were not statistically significant

Figure 2. Logistic curves of Static-99R for Indigenous and White study groups with the High Risk/High Need Norms with a fixed 10-year follow-up.

Image description

This figure illustrates the logistic curves of Static-99R for Indigenous and White study groups with the High Risk/High Need Norms with a fixed 10-year follow-up showing the 10-year sexual recidivism rates at a Static-99R score of 2 for the Indigenous study group were similar to that of the White study group (11.9% versus 9.7%). The discrimination (change in relative risk) was higher for the White study group than for the Indigenous study group with both 5-year (odds ratios = 1.21 versus 1.36) as well as 10-year follow-up periods (1.31 versus 1.41), but these differences in discrimination between racial groups were not statistically significant

Calibration. For the Indigenous study group, when compared to the high-risk/high-needs norms (from Hanson et al., 2016), the adjusted (score of 2) base rate with a fixed 5-year follow-up period was slightly lower (11.3% versus 10.2%) and the discrimination was smaller (odds ratios = 1.28 versus 1.21), but those differences were not statistically significant (Table 7; Figure 1). With a fixed 10-year follow-up period, the adjusted (score of 2) base rate for the Indigenous study group was lower (19.2% versus 11.9%), and the discrimination was larger for the Indigenous study group compared to the norms (odds ratios = 1.26 versus 1.31), but those differences were not statistically significant (Table 7; Figure 2).

For the White study group, when compared to the high-risk/high-needs norms (from Hanson et al., 2016), the adjusted (score of 2) base rate with a fixed 5-year follow-up period was significantly lower (11.3% versus 5.7%) and the discrimination was larger (odds ratios = 1.28 versus 1.36), but not significant (Table 7; Figure 1). With a fixed 10-year follow-up period, the adjusted (score of 2) base rate for the White study group was significantly lower (19.2% versus 9.7%), and the discrimination was larger (odds ratios = 1.26 versus 1.41), but not significantly so (Table 7; Figure 2).

Static-2002R

Compared to those of Static-99R, the sample size of the Indigenous study group for the Static-2002R was reduced to 173 (3 studies) with a 5-year follow-up period and 101 (2 studies) with a 10-year follow-up period.

Discrimination. The Static-2002R was able to discriminate recidivists from non-recidivists for the White study group (AUCs > .69). The predictive accuracy of Static-2002R for the Indigenous study group was, however, lower (AUCs < .61) and not statistically significant (Table 8).

Study |

Indigenous |

White |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sexual Recidivism |

AUC |

Sexual Recidivism |

AUC |

||||||

% |

n/N |

% |

n/N |

||||||

Fixed 5-year |

|||||||||

Haag (2005) |

28.0 |

14/50 |

.56 [.36, .75] |

17.7 |

25/141 |

.69 [.59, .80] |

|||

Brankley et al. (2017) |

11.4 |

4/35 |

.57 [.27, .87] |

11.4 |

35/308 |

.70 [.61, .79] |

|||

Lee et al. (2018) |

19.3 |

17/88 |

.56 [.42, .70] |

15.8 |

27/171 |

.69 [.59, .79] |

|||

Average (fixed-effect) |

20.2 |

35/173 |

.56 [.45, .67]ns |

14.0 |

87/620 |

.69 [.64, .75] ns |

|||

Fixed 10-year |

|||||||||

Brankley et al. (2017) |

20.0 |

7/35 |

.64 [.40, .88] |

21.7 |

65/299 |

.74 [.67, .80] |

|||

Lee et al. (2018) |

28.8 |

19/66 |

.60 [.45, .75] |

23.1 |

27/117 |

.69 [.58, .81] |

|||

Average (fixed-effect) |

25.7 |

26/101 |

.61 [.49, .74] ns |

22.1 |

92/416 |

.72 [.67, .78] ns |

|||

Note: ns indicates no significant variability across studies (Q statistics). Numbers in bold indicate statistical significance (i.e., p < 0.05). |

|||||||||

Similar to the outcomes of Static-99R, there were very consistent base rates and relative risk levels of Static-2002R across studies within each racial group. Specifically, for the Indigenous study group, both the 5-year (3 studies) and 10-year sexual recidivism rates (2 studies) with a Static-2002R score of 3 (B03) across the studies were very similar (both p > .40; Table 9). The overall outcomes of Static-2002R, however, did not seem to be stable given the small number of studies in the meta-analysis. For example, the average base rate (B03) within a fixed 5-year follow-up (16.4%) was higher than that within a fixed 10-year follow-up (14.3%) because there were a different number of studies in each analysis. The relative risk (B1) of the Static-2002R across the studies was also very similar with a fixed 5-year follow-up (3 studies) as well as with a fixed 10-year follow-up (2 studies; both p > .60; see Table 9). Nevertheless, the relative risk (i.e., odds ratios) of the Static-2002R was not statistically significant (i.e., poor discrimination; Table 9).

Study |

Base rate (Static-2002R score of 3 in logit units) |

Relative risk |

Odds Ratio |

95% C.I. |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

B03 |

SE |

B1 |

SE |

Lower |

Upper |

||||||

Fixed 5-year |

|||||||||||

Haag (2005) |

- 1.212 |

(22.9%) |

.600 |

.092 |

.171 |

1.09 |

0.76 |

1.43 |

|||

Brankley et al. (2017) |

- 2.540 |

(7.3%) |

1.124 |

.142 |

.268 |

1.15 |

0.63 |

1.68 |

|||

Lee et al. (2018) |

- 1.768 |

(14.6%) |

.563 |

.093 |

.132 |

1.10 |

0.84 |

1.36 |

|||

Q (df = 2) |

1.20, p = .549 |

0.03, p = .985 |

|||||||||

I2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|||||||||

Average (fixed-effect) |

- 1.630 |

(16.4%) |

.386 |

.099 |

.097 |

1.10 |

0.91 |

1.34 |

|||

Fixed 10-year |

|||||||||||

Brankley et al. (2017) |

- 2.437 |

(8.0%) |

.997 |

.293 |

.229 |

1.34 |

0.89 |

1.79 |

|||

Lee et al. (2018) |

- 1.560 |

(17.4%) |

.591 |

.178 |

.137 |

1.19 |

0.93 |

1.46 |

|||

Q (df = 1) |

0.42, p = .449 |

0.19, p = .667 |

|||||||||

I2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|||||||||

Average (fixed-effect) |

- 1.788 |

(14.3%) |

.509 |

.208 |

.117 |

1.23 |

0.97 |

1.55 |

|||

For the White study group, both the 5-year (3 studies) and 10-year sexual recidivism rates (2 studies) with a Static-2002R score of 3 (B03) across the studies were very similar (both p > .20; Table 10). The relative risk (B1) of Static-2002R across the studies was also very similar with a fixed 5-year follow-up (3 studies) as well as with a fixed 10-year follow-up (2 studies; p > .20; Table 10).

Study |

Base rate (Static-2002R score of 3 in logit units) |

Relative risk |

Odds Ratio |

95% C.I. |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

B03 |

SE |

B1 |

SE |

Lower |

Upper |

|||||

Fixed 5-year |

||||||||||

Haag (2005) |

- 2.506 |

(7.5%) |

.427 |

.313 |

.100 |

1.37 |

1.17 |

1.56 |

||

Brankley et al. (2017) |

- 3.200 |

(3.9%) |

.407 |

.314 |

.085 |

1.37 |

1.20 |

1.53 |

||

Lee et al. (2018) |

- 2.561 |

(7.2%) |

.410 |

.248 |

.085 |

1.28 |

1.11 |

1.45 |

||

Q (df = 2) |

1.76, p = .415 |

0.37, p = .829 |

||||||||

I2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

||||||||

Average (fixed-effect) |

- 2.765 |

(6.0%) |

.239 |

.289 |

.052 |

1.34 |

1.21 |

1.48 |

||

Fixed 10-year |

||||||||||

Brankley et al. (2017) |

- 2.686 |

(6.4%) |

.332 |

.391 |

.072 |

1.48 |

1.34 |

1.62 |

||

Lee et al. (2018) |

- 2.040 |

(11.5%) |

.406 |

.258 |

.089 |

1.29 |

1.12 |

1.47 |

||

Q (df = 1) |

1.52, p = .220 |

1.36, p = .248 |

||||||||

I2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

||||||||

Average (fixed-effect) |

- 2.427 |

(8.1%) |

.257 |

.338 |

.056 |

1.40 |

1.26 |

1.56 |

||

Note. Numbers in bold indicate statistical significance (i.e., p < 0.05). |

||||||||||

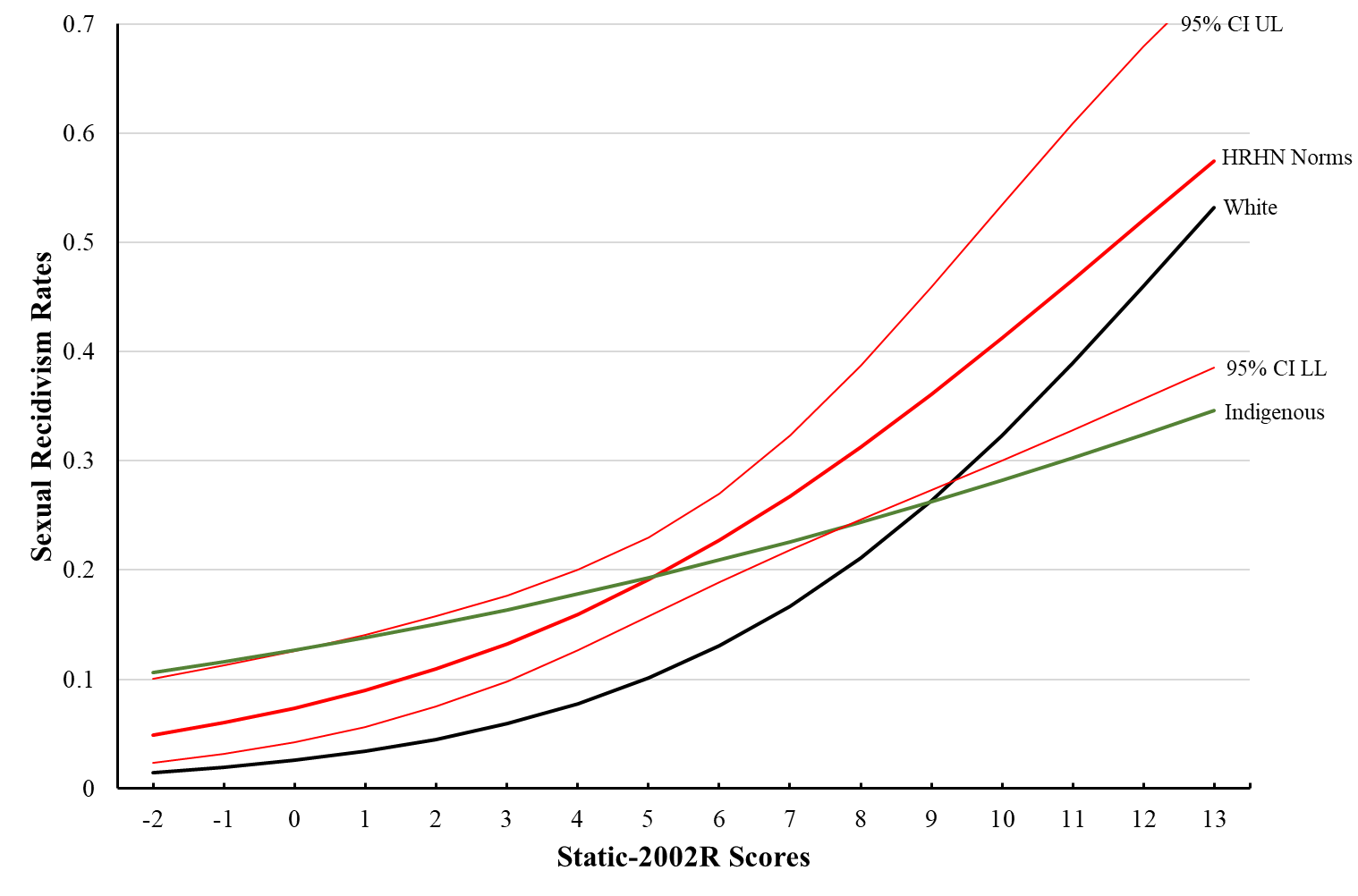

The 5-year sexual recidivism rates with a Static-2002R score of 3 for the Indigenous study group were significantly higher than that of the White study group (16.4% versus 6.0%; Table 11; Figure 3). The 10-year sexual recidivism rates with a Static-2002R score of 3 for the Indigenous study group were also higher than that of the White study group, but the difference was not statistically significant (14.3% versus 8.1%). The discrimination (change in relative risk) was higher for the White study group than the Indigenous study group for both 5-year (odds ratios = 1.10 versus 1.34) and 10- year follow-up periods (1.23 versus 1.40); however, the difference between racial groups was statistically significant only for the 5-year follow-up period (Table 11; Figure 3).

Meta-Average (HRHN Norms) |

Indigenous |

White |

B Indigenous-White |

95% C.I. |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Fixed 5-year |

|||||||||

Base rate |

|||||||||

B03 (SD) |

- 1.88 (.153) (13.2%) |

- 1.63 (.386) (16.4%) |

- 2.76 (.239) (6.0%) |

1.135 |

[0.402, 1.868] |

||||

QΔ (df = 1) |

0.36 |

9.75** |

|||||||

Relative risk |