Examining Key Populations in the Context of Implementing Cyberbullying Prevention and Intervention Initiatives

Literature Review on 2SLGBTQ+, Girls, and Ethno-racially Diverse Youth

By Nishad Khanna, Eva Maxwell, Dr. Wendy Craig

Abstract

This report reviewed literature on the cyberbullying experiences of young people who are minoritized based on their gender, sexuality and/or ethno-racial identities to inform cyberbullying prevention and intervention initiatives. Using a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria and keywords to scan academic databases and sources of grey literature, a total of 162 articles were analyzed. The research is relatively recent and has a largely Western world focus, owing to a review of only English studies. There are limited studies on risk and protective factors and even fewer intervention studies to inform cyberbullying prevention and intervention initiatives for minoritized youth. Though few, findings suggest that cyberbullying programs can target the protective and risk factors for minoritized youth. Offline bullying victimization is a common key risk factor of cybervictimization for minoritized youth. Thus, programs designed to prevent and intervene in targeted offline bullying may be effective at reducing the risk of cybervictimization and mediating the associated impacts. In addition, there are several key factors that may be effective elements of prevention and intervention initiatives: connectedness (e.g., family support, school connectedness) for 2SLGBTQ+ youth; mental health support for girls and young women; and opportunities to build a stronger sense of ethno-racial identity for ethno-racial minorities. This report recommends supplementary research to address research opportunities and gaps; the development and evaluation of initiatives based on risk and protective factors; and leveraging existing partnerships and networks of minoritized youth and their communities to support relevant initiatives, social policy, and social change.

Author's Note

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Public Safety Canada. Correspondence concerning this report should be addressed to:

Research Division

Public Safety Canada

340 Laurier Avenue West

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0P8

Email: PS.CPBResearch-RechercheSPC.SP@canada.ca

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Jennifer Martin, Dr. Andrea Slane, Fiona Amara, Reem Atallah, Kelly Gillis, Emma May Liptrot, Catherine Moleski, and Katy Celina Sandoval.

Introduction

Purpose

The main intent of this report is to provide a comprehensive review of recent advances in cyberbullying research and knowledge, with a specific focus on different gender, sexual and/or ethno-racial minority groups (youth and young adults) in Canada and internationally. A previous literature review “Cyberbullying research in Canada: A systematic review” (Zych et al., 2020) conducted for Public Safety Canada revealed that there is a gap in knowledge in this area. Thus the primary objective of this cyberbullying review is to focus on recent literature and examine the prevalence of cyberbullying perpetration and victimizations among gender and ethnic minority groups in Canada and abroad; the impacts of cyberbullying on youth and young adults in different minority groups; how ethnicity and gender are understood as risk factors and protective factors and the specificity of factors associated with different ethnic and gender minorities; the considerations that should be made in order to better protect minority groups from cyberbullying; and the remaining gaps in research and understanding in relation to cyberbullying among different minority groups. This report will present a systematic review of academic literature and grey literature, from Canada and abroad, on the topic.

Context

Cyberbullying has been defined as “any behaviour performed through electronic or digital media by individuals or groups that repeatedly communicates hostile or aggressive messages intended to inflict harm or discomfort to others” (Tokunaga, 2010, p. 278) and thus refers to willful and repeated harm, done through the use of electronic devices (cellphones, computers, etc.) (Patchin & Hinduja, 2015). This definition is changing with the ever-evolving nature of online activities and interactions, however; cyberbullying behaviours can take many forms (e.g., harassment, cyberstalking, outing/doxing, trolling, exclusion, fake profiles, etc.). Indeed, another definition of cyberbullying refers to “using information and communication technologies (ICT) to repeatedly and intentionally harm, harass, hurt and/or embarrass a target” (Peter & Petermann, 2018, p. 358). Some of the differences between online and offline bullying include anonymity, greater social dissemination, lack of supervision, and greater accessibility.

Unfortunately, cyberbullying is a common occurrence among children, youth and young adults. Of note, in 2014, the General Social Survey on Victimization in Canada found that approximately “17% of the Canadian population aged 15 to 29 that accessed the Internet at some point between 2009 and 2014, reported they had experienced cyberbullying or cyberstalking” (Hango, 2016). The recent Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children study published by the Public Health Agency of Canada also provides statistics about bullying and cyberbullying incidences among youth, shedding light, for example, on the reporting of cyberbullying by girls versus boys, “girls are more likely to report being cyber-victimized than boys. For example, 16% of girls in grade 10 and 9% of boys in grade 10 report being cyber-victimized” (Craig. et al., 2020)Footnote 1. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing requirements, cyberbullying has become more salient. Furthermore, racist cyberbullying targeting East and Southeast Asian youth has increased (Alsawalqa, 2021; Cheah et al., 2020).

Cyberbullying is particularly harmful to those who are victimized. Some researchers suggest that online bullying can, in some cases, have more serious consequences than traditional victimization. Victims of cyberbullying may experience various emotional, social, and academic problems (e.g. anxiety, depression, self-denigration, poor relationships, isolation, aggression, etc.) and consequences (e.g. decreased academic performance, poor concentration, etc.). They may also suffer from reminders and revictimization every time they go online. Indeed, there is a continuum of harm with cyberbullying, and, in some cases, severe consequences may include suicide and suicidal ideation (Hinduja & Patchin, 2010). Cyberbullying is particularly difficult to address due to the issues of anonymity; widespread access to Internet/social media, particularly in urban contextsFootnote 2; the potential for behaviours to “go viral”; private/inaccessible platforms, apps and websites; the difficulty of removing offensive material; the dissemination of private information and photographs and the legal framing thereof; youth possession of sensitive images, etc. Furthermore, cyberbullying deploys various types of violence that specifically target gender, sexual, and ethnic minorities, including racial and gender-based violence.

In light of the overall prevalence of cyberbullying, the specific experiences of different gender, sexual and ethnic minority groups (i.e., girls/women, trans people, queer populations, racialized populations, Indigenous populations, etc.) may be substantialFootnote 3, although related literature is limited. Where research is available, this literature review seeks to shed greater light on different gender, sexual, and ethnic minority groups (i.e., prevalence, risk factors, protective factors, impacts, etc.), in order to help inform the development and implementation of policies and programs aimed at addressing and reducing cyberbullying directed at and among these subgroups.

Rationale

Public Safety Canada seeks to further understand the most promising practices and keep abreast of the latest knowledge and research relating to cyberbullying. In this regard, Public Safety Canada has conducted an environmental scan of programs (Directions Evidence and Policy Research Group, LLP, 2019) and a literature review on cyberbullying (Zych et al., 2020) and is interested in learning more about the gaps that were highlighted as key areas of focus. Thus, this literature review will take a deeper look at the specific experiences of different ethnic, gender, and sexual minority groups (youth and young adults) in the context of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization, with a view to informing future policy and program design for Canadian federal government programming aimed at reducing cyberbullying. This effort will contribute to Public Safety Canada/the Government of Canada's broader priorities and agenda focusing on reducing crime and enhancing community safety through prevention, policing, and corrections.

Objective and Research Questions

The primary objective of the work is to provide a comprehensive report on recent advances in cyberbullying research and knowledge, with a specific focus on different gender, sexual and ethnic minority groups (youth and young adults) in Canada and internationally. Gender minorities are defined as populations whose genders are minoritized in our society (e.g., trans, gender-queer, non-binary, Two-Spirit). Sexual minorities are defined as populations whose sexualities are minoritized in our society (e.g., Two-Spirit, lesbian, bisexual, pansexual). Ethno-racial minorities are defined as populations whose ethnicities and/or racial identities are minoritized in our society (e.g., racialized, Indigenous, immigrant). This report will explore:

- The prevalence of cyberbullying perpetration among gender, sexual and ethnic minority groups in Canada and abroad;

- The prevalence of cyberbullying victimization among gender, sexual and ethnic minority groups in Canada and abroad;

- The short and long-term impacts of cyberbullying on youth and young adults in different gender, sexual, and ethnic minority groups, and the extent to which the impacts differ between groups;

- How the intersectionality of various minority group memberships (gender, sexuality, ethnicity) uniquely impacts youth and young adults' experiences with cyberbullying;

- Which risk factors/protective factors are most important to identify and address in order to prevent and intervene in incidences of cyberbullying (both perpetration and victimization) among different minority groups;

- The considerations, if any, that have been made within existing cyberbullying prevention and intervention initiatives for different minority groups;

- The considerations that can/should be made in cyberbullying prevention and intervention initiatives in order to better address cyberbullying among different minority groups; and

- The remaining gaps in research and understanding in relation to cyberbullying among different minority groups.

Methodology

Scope of Research and Search Parameters

This review is limited to literature written in English available through web searches from the early 2000s to August 2021, appearing in electronic databases (academic journal articles/peer reviewed articles and book chapters) and in select sources of grey literature (e.g., government publications) and does not include consultations or interviews. The search included Canadian and international literature.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Documents were screened according to the following inclusion and exclusion criteria:

- Studies were included if cyberbullying was explicitly measured through a specific instrument (scale, observation, peer nominations, etc.). Studies where cyberbullying was mentioned, but not measured, were excluded.

- This literature review focuses specifically on cyberbullying. Thus, cyberbullying was analyzed as a separate variable, not as a part of general bullying. Papers that measured cyberbullying as a part of bullying and treated bullying and cyberbullying as a single variable were excluded.

- Studies were included if they present quantitative or qualitative results about cyberbullying in Canada and internationally.

- Empirical studies (i.e. studies that include original research results) were included. Review studies (i.e. studies that include reviews of other studies, without original research results) were excluded.

- Research published in English was included.

- Research that appears in a peer review article, or government report were included (sources are listed in the references section).

- Studies were included if they involve children, youth, and/or young adults (8-25 years of age).

Data Collection and Analysis

Data Collection

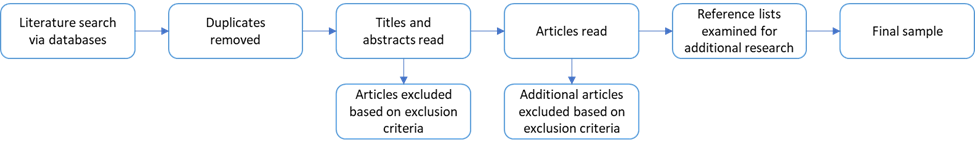

The data collection started with a scan of databases (listed below) and all other relevant sources of literature (e.g., online/web scans) using the list of keywords found under the subsection entitled “Keywords.” Articles found within the date range (2000s to August 2021) were compiled into a common database (Zotero). Subsequently, all articles were reviewed with a view to sorting and prioritizing the most relevant sources. Sources were checked for validity and reliability, ensuring that they are supported by rigorous methodology, containing findings that are relevant for this study. As per Figure 1 below, exclusion and inclusion criteria were applied to arrive at a final sample. Of particular interest were sources that address or answer the research questions and objectives identified above.

Figure 1: Article Selection Process

Figure 1 – Text version

Selection Step |

Exclusion Step |

|

|---|---|---|

Step 1 |

Literature search via databases |

|

Step 2 |

Duplicates removed |

|

Step 3 |

Titles and abstracts read |

Articles excluded based on exclusion criteria |

Step 4 |

Articles read |

Additional articles excluded based on exclusion criteria |

Step 5 |

Reference lists examined for additional research |

|

Step 6 |

Final sample |

A matrix was used to capture summary data from each of the sources, for comparability and synthesis of findings. The table captured the following fields:

- Article title

- Author(s)

- Date of publication

- Location (country) of research

- Sample (number of participants, age range of participants, ethnicity, gender)

- Design (longitudinal/cross sectional; qualitative or quantitative; mixed methods)

- Key constructs measured (name of scales and reference)

- Key findings

- Limitations

Additionally, a table was used to summarize data on the prevention and intervention initiatives capturing the following fields:

- Article title

- Author(s)

- Date of publication

- Location (country) of research

- Sample (number of participants, age range of participants, ethnicity, gender)

- Prevention/ intervention?

- Name of program

- Type of treatment (individual/group/whole school)

- Theory of change, if mentioned

- Length of treatment

- Design (longitudinal/cross sectional; qualitative or quantitative)

- What was assessed (measures and reference)

- Key Results

- Specific impact on minority groups evaluated? (yes/no)

Analysis

Texts were analyzed qualitatively using a content analysis approach (i.e., qualitative, inductive content analysis of both manifest and latent content), through which patterns, themes, tendencies, and trends that are present in the sources were identified. During this process, all sources were reviewed to determine emerging key themes and code words.

Next, all literature were processed, applying codes to the text. These codes were grouped thematically in a process of decontextualization (breaking down the texts into smaller meaning units) and eventual recontextualization and categorization (identification of themes, categories in order to arrive at findings). The principal intent of content analysis is to interpret the patterns, themes, and categories arising from the literature to arrive at a set of overall findings, aligned with the research questions and objectives.

Conclusions were drawn from the coded data (e.g., the principal themes and patterns that have emerged from the data; how the data and findings relate to the research questions; and the sense and general conclusions that arise from the current research). Trends in the type or research being produced on cyberbullying prevention and intervention were also identified, to inform potential future research needs or gaps.

Sources

The following sources were searched for relevant articles:

Academic Databases

- ProQuest Social Sciences

- PUBMED

- Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

- EMbase

- Psycinfo

- ISI Web of Science

- Scopus

- The Cochrane database of Systematic Reviews

- The Campbell Collaboration

- Social Services Abstracts

- Social Work Abstracts, Sociological Abstract

- Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) and Education Research Complete

- Grey literature to be identified by searching key websites known for producing or disseminating relevant research on this topic, including, for example:

- Women and Gender Equality Canada

- Public Safety Canada

- Department of Justice

- Statistics Canada

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- Virtual Knowledge Center to End Violence Against Women and Girls

- Population Reference Bureau

- Eldis - Gender-based violence (GBV)

- Violence Prevention

- GBV Prevention Network

- Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence - Institute of Behavioral Science

- SVRI Website

- Campbell Systematic Reviews

- UNICEF Online Library

- WHO Publications

- PREVnet

- the American Evaluation Association

- the Canadian Evaluation Society

- Public Safety Canada's Crime Prevention Inventory

- National Online Resource Center on VAW

Keywords

The keywords that were used for finding articles are presented below. These keywords (and their close variants to account for spelling, synonyms, word endings, etc.) were used in conjunction with other search parameters (e.g., date, location) and may be combined into phrases (i.e. using “and”/“or”).

Aboriginal; academic outcomes; adolescent; African-American; aggression; Asian; BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Colour); black; body shaming; boys; cyber aggression; cyber bullying; cyber intimidation; cyber stalking; cyber perpetration; cyber victimization; cyberaggression; cyberbullying; cybervictimization; deadnaming; electronic bullying; ethnic minorities; gender; gender minorities; gender non conforming; girls; homophobia; immigrant; Indigenous; Indigenous (First Nations; Inuit; Metis); internet bullying; intervention; Inuit; Islamophobia; LGBTQ2S+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, two-spirit); long-term impacts; mental health; mental outcomes; Metis; minority groups; misogyny; misgendering; mobile; Native; Native American; newcomer; non-binary; perpetration; physical outcomes; POC; prevention; protective factors; queer; racial discrimination; racialized; racial minority; racialized; racism; refugee; risk factors; sexual harassment; sexual minority; short-term impacts, social media; social outcomes; systemic factors (individual, peer, school, community); teenager; trans; transphobia; two-spirit; victimization; visible minority; young adult; youth.

Findings

Study Characteristics

Initially 246 academic articles were collected. These included 231 articles related to the cyberbullying experiences of gender, sexual and ethno-racial minority youth and 15 articles specifically about cyberbullying prevention and/or intervention initiatives. Eighty-eight articles were excluded because they either did not analyze cyberbullying as an independent variable; did not have any relevant findings related to minoritized youth; did not focus on youth; or were literature reviews, book chapters or PhD dissertations. In addition, 10 grey literature articles and documents were collected and four were excluded because they did not have findings or recommendations specific to cyberbullying and minoritized youth. A total of 162 articles were analyzed overall (156 academic articles and 6 from the grey literature). The full list of references can be found in the reference list. Table 1 summarizes the collection, exclusions and inclusions. Of note, due to the limited number of articles identified for the review, many of the findings are based on few studies and should be with interpreted with caution.

Initial collection |

Exclusions |

Included articles |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Academic articles: Cyberbullying experiences of minoritized youth |

231 |

81 |

150 |

Academic articles: Prevention and intervention initiatives |

15 |

9 |

6 |

Grey literature |

10 |

4 |

6 |

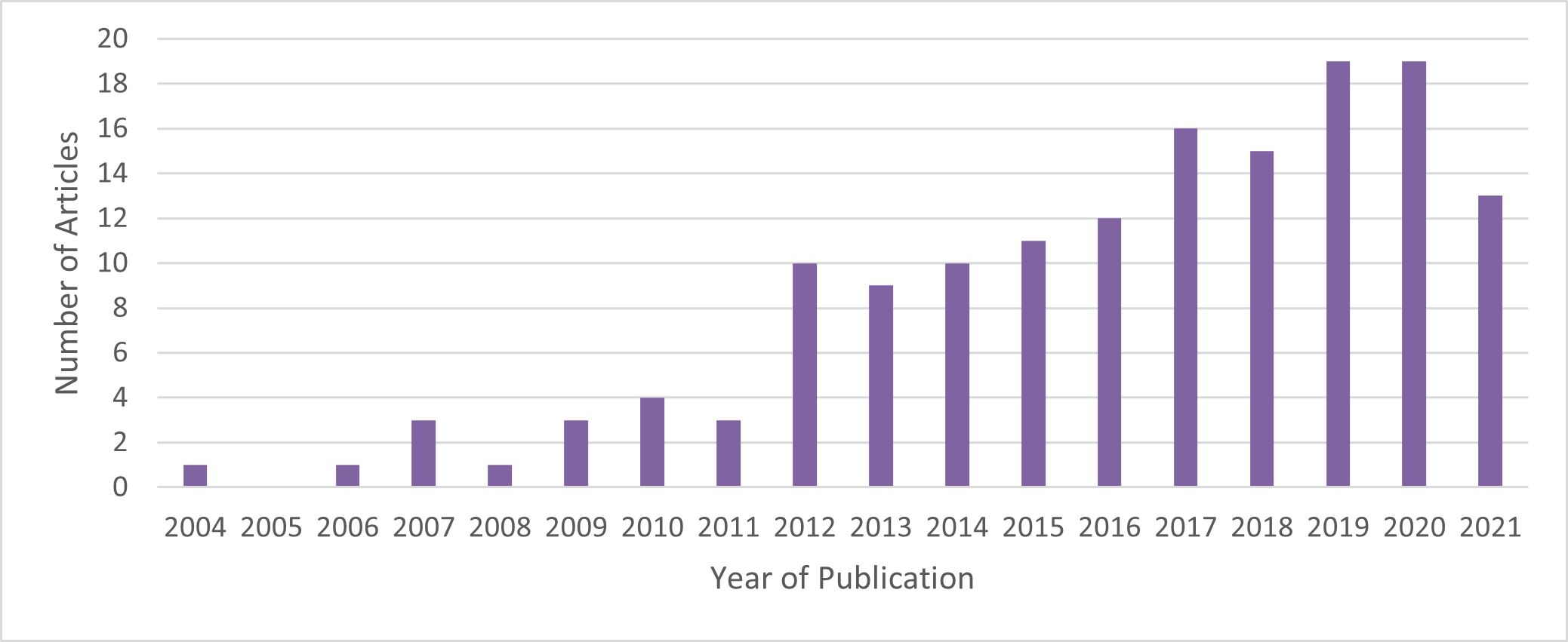

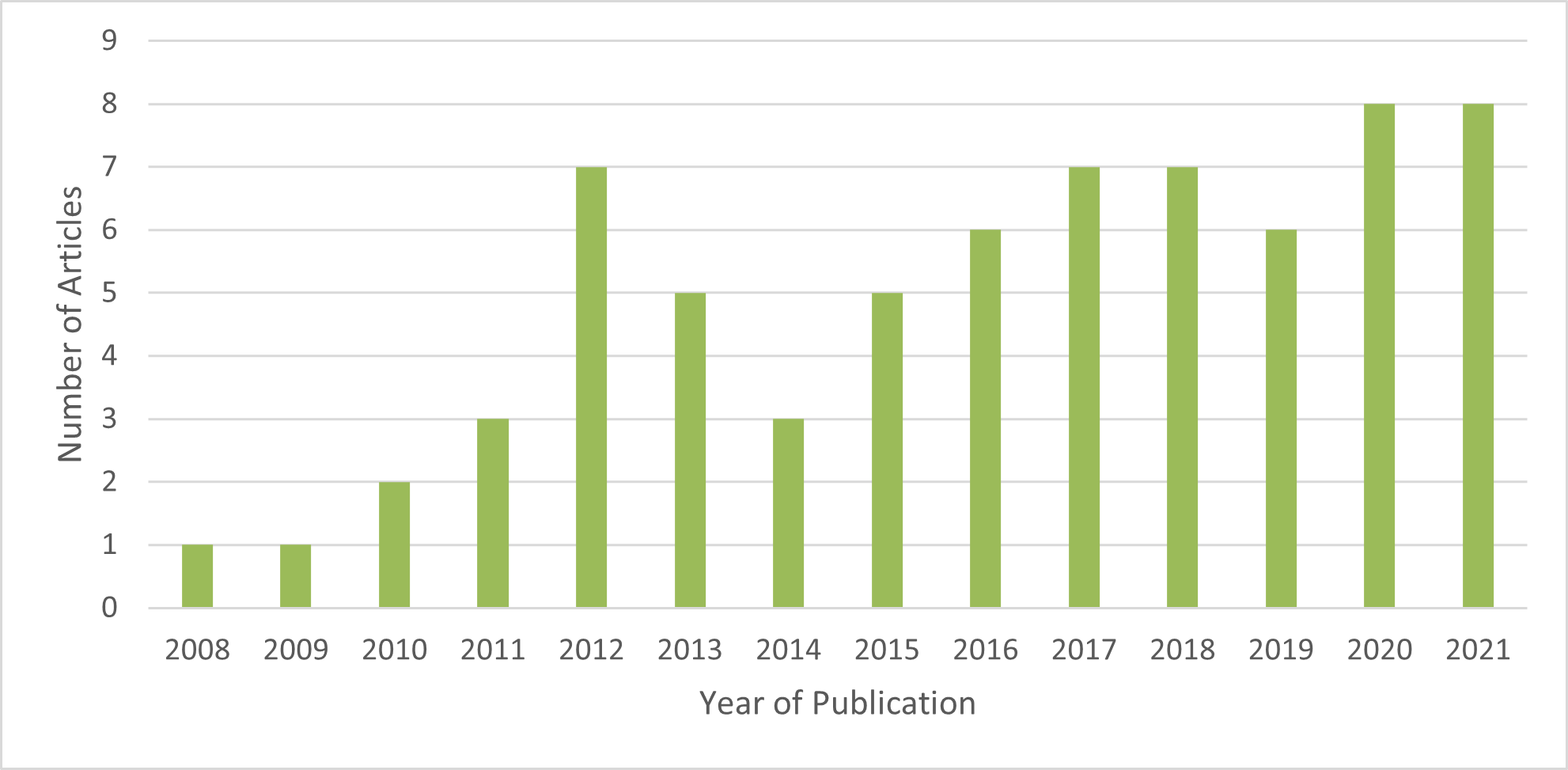

Dates of Publication

A total of 150 articles focusing on the cyberbullying experiences of youth minoritized due to their gender, sexual and ethno-racial identity were analyzed. Articles dated from 2004 to 2021, with only 16 from between 2004-2011 and most studies published over the last 10 years. The highest number of studies were published in 2019 and 2020. This demonstrates the newness of the focus on minoritized youth and cyberbullying. Figure 2 illustrates the recent growing number of studies focusing on cyberbullying experiences of minoritized youth.

Figure 2: Year of publication of studies related to gender, sexual and ethno-racial minority youth

Figure 2 – Text version

Year of Publication |

Number of Articles |

|---|---|

2004 |

1 |

2005 |

0 |

2006 |

1 |

2007 |

3 |

2008 |

1 |

2009 |

3 |

2010 |

4 |

2011 |

3 |

2012 |

10 |

2013 |

9 |

2014 |

10 |

2015 |

11 |

2016 |

12 |

2017 |

16 |

2018 |

15 |

2019 |

19 |

2020 |

19 |

2021 |

13 |

Methodology and Research Design

With regards to methodology, 89% of the articles (n=134) used quantitative analysis. Ten articles employed a mixed methods approach and only six used qualitative analysis. The newness of this field of research is also evident in the research design: 89% (n=133) were cross-sectional and 17 were longitudinal. The longitudinal studies ranged from 2 months to 10 years in length.

Samples

Sample sizes in the studies ranged from 18 to 214,080 (the largest study included participants from 41 countries). Sample ages ranged from children 8 years old to young adults up to 29 years old. Some studies included older people (up to 67 years) but were only included if results were disaggregated by age and/or were relevant to understand long-term impacts of cyberbullying.

Location

A total of 47 countries were listed in the articles reviewed.Footnote 4 The distribution of countries represented in these studies likely reflects the limitation of this literature review to English articles. Consequently, there is an overrepresentation of majority white populations in the Western world and studies that are embedded in a Western worldviewFootnote 5. The greatest representation is from the United States (95 studies), followed by Canada (26 studies), Spain (10 studies), and Taiwan (6 studies). Table 2 summarizes the number of articles by country.

Country (in descending frequency) |

Number of articles |

|---|---|

United States |

95 |

Canada |

26 |

Spain |

10 |

Taiwan |

6 |

Finland |

3 |

Netherlands |

3 |

Portugal |

3 |

Sweden |

3 |

United Kingdom |

3 |

Austria |

2 |

Australia |

2 |

Belgium |

2 |

Bulgaria |

2 |

Denmark |

2 |

Germany |

2 |

Israel |

2 |

Turkey |

2 |

Armenia |

1 |

Cyprus |

1 |

Brazil |

1 |

Croatia |

1 |

Czech Republic |

1 |

Estonia |

1 |

France |

1 |

Greece |

1 |

Greenland |

1 |

Hungary |

1 |

Iceland |

1 |

Ireland |

1 |

Italy |

1 |

Japan |

1 |

Jordan |

1 |

Latvia |

1 |

Lithuania |

1 |

Luxembourg |

1 |

Malaysia |

1 |

Malta |

1 |

Norway |

1 |

Poland |

1 |

Romania |

1 |

Russian Federation |

1 |

Slovakia |

1 |

Slovenia |

1 |

Switzerland |

1 |

Thailand |

1 |

Ukraine |

1 |

Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia |

1 |

Terminology

- Cis-gender

- Someone whose gender identity is aligned with the sex assigned to them at birth.

- Cyber-perpetration

- “The use of information and communication technology (ICT), such as instant messaging, e-mail, text messaging, blogs, and social media, by adolescents in the victimization or bullying of their peers” (Chan & Wong, 2019, p. 5).

- Cybervictimization

- Intentional and repeated harm inflicted through the use of technology; individuals who are at the receiving end of cyberbullying behaviors are considered cyber victims (Kalia & Aleem, 2017).

- Gender expansive

- An umbrella term for people who are exploring a wider and more flexible range of gender identity and/or expression possibilities than typically associated with the binary gender system (e.g., non-binary, genderfluid, gender creative, gender non-conforming).

- Gender minority

- Populations that are systemically minoritized based on their gender. Although not a statistically minority, the experiences of cisgender girls are also included in this report, but separated from gender minorities (e.g., trans, gender expansive) where appropriate.

- Ethno-racial minority

- Populations that are systemically minoritized based on their ethnic and/or racial identities.

- 2SLGBTQ+

- 2SLGBTQ+ is an acronym for Two-Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Queer. The “+” acknowledges that this acronym is not exhaustive and that there are other identities that are not explicitly listed (e.g., asexual, pansexual, questioning). Other variations of the acronym (e.g., LGBT, LGBQ) are used throughout the report to separate findings related to sexual and gender minorities.

- Minoritization

- A process that positions some subgroups as “outsiders to dominant norms and consequently seen to fall short of the standards of the dominant group” (de Finney et al., 2011; p.361). Minoritization produces inequities for youth, their families, and their communities.

- Polyvictimization

- Exposure to multiple victimizations. In the context of this report, polyvictimization refers to exposure to both face-to-face bullying and cyberbullying.

- Sexual minority

- Populations systemically minoritized based on sexual orientation.

- Trans

- Trans is used as a short and more inclusive version of “transgender”. It is an umbrella term for people whose gender identity and/or expression does not align with cultural expectations of gender based on the sex they were assigned at birth.

- Vicarious cybervictimization

- Exposure to online victimization that is directed at one's community (e.g., ethno-racial group) or at others with whom one shares a minoritized identity and/or experience.

Sexual Minority Youth

This section focuses on cyberbullying involving sexual minority youth in Canada and abroad. Specifically, differences in cybervictimization and cyber-perpetration experiences, risk and protective factors, and outcomes will be explored. The acronym LGBQ+ is used throughout this section to specifically identify those in the 2SLGBTQ+ community who are minoritized by their sexual orientation. Trans and gender expansive youth are included in the following section about gender minority youth.Footnote 6

Studies categorized young people minoritized by sexual orientation in different ways. In some studies, they were disaggregated with different combinations of the following identifiers (e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual, pansexual, questioning, queer, unsure, mostly heterosexual), while other studies dichotomized the variable (e.g., sexual minority, non-sexual minority/heterosexual).

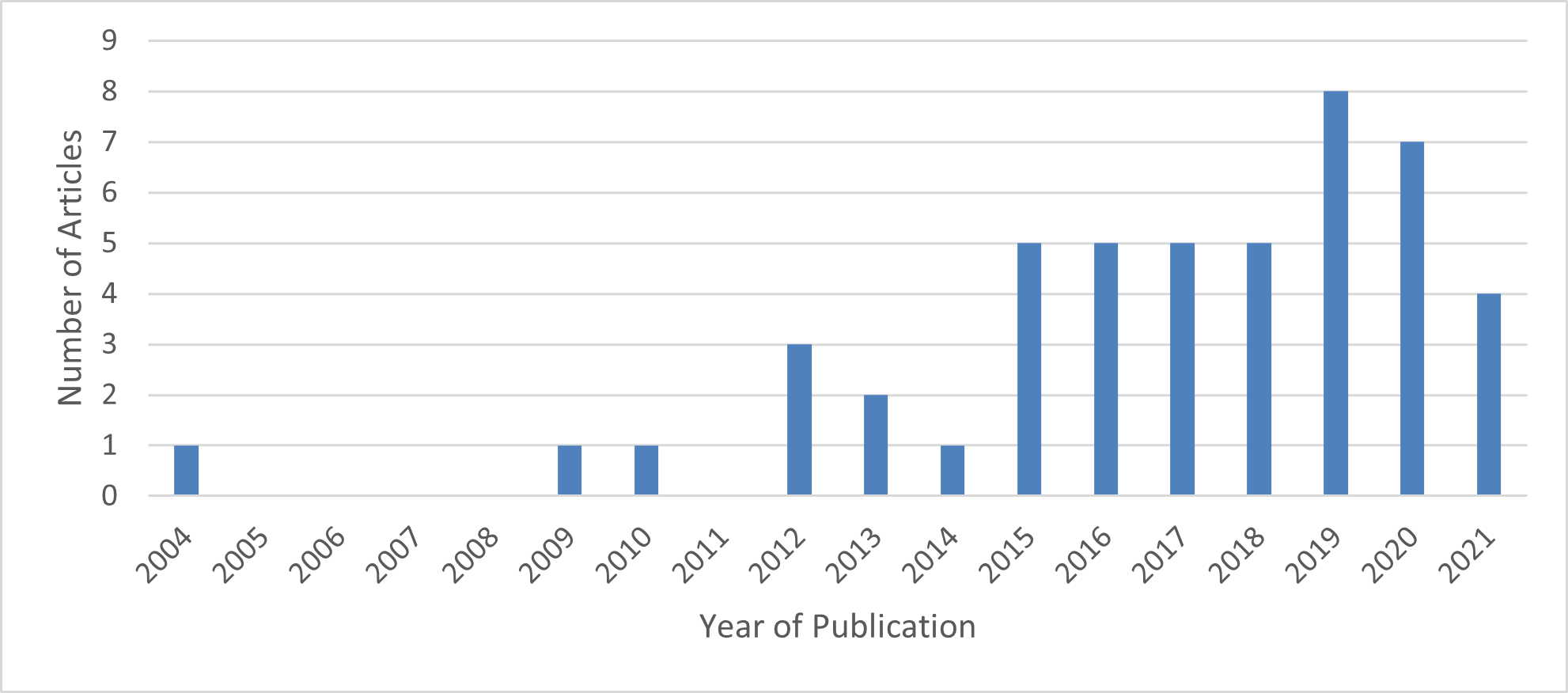

Study Characteristics

Forty-seven articles included findings related to LGBQ+ youth and all but five of these had an explicit focus in the title or primary research questions about sexual minority youth. Almost all are quantitative (n=43), two are qualitative, and two are mixed methods studies. Only two studies were longitudinal. Figure 3 depicts the year of publication for studies focused on cyberbullying experiences of LGBQ+ youth. The majority of studies were published in the last seven years.

Figure 3: Year of publication of articles related to sexual minority youth

Figure 3 – Text version

| Year of Publication | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

2004 |

1 |

2005 |

0 |

2006 |

0 |

2007 |

0 |

2008 |

0 |

2009 |

1 |

2010 |

1 |

2011 |

0 |

2012 |

3 |

2013 |

2 |

2014 |

1 |

2015 |

5 |

2016 |

5 |

2017 |

5 |

2018 |

5 |

2019 |

8 |

2020 |

7 |

2021 |

4 |

Most of these studies were conducted in Western countries, with thirty from the United States and a cluster of studies (n=6) based on the same sample in Taiwan. Only three of the studies were from Canada. The rest of the studies came from Australia (n=2), Belgium (n=1), and Sweden (n=1).

Prevalence of Cyberbullying Victimization

LGBQ+ youth report experiencing cybervictimization at significantly higher levels than their heterosexual counterparts. This finding was consistent across all studies that compared prevalence of cybervictimization among sexual minority youth and heterosexual youth (N=32). Furthermore, one study examining minority status and cyberbullying found that only sexual minority status correlated with cyberbullying involvement (cybervictimization and cyber-perpetration), whereas other minoritized status (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender and socioeconomic) did not (Duarte et al., 2018).

Within sexual minorities, some youth are more minoritized and at even higher risk of cybervictimization. Bisexual and pansexual youth (Angoff & Barnhart, 2021; Myers et al., 2017; Ybarra et al., 2015), sexual minority youth in rural areas (Marra, 2013), and boys who identify as sexual minorities (Levine & Button, 2021; Llorent et al., 2016; Wensley & Campbell, 2012) are at higher risk of cybervictimization.

Nature of Cybervictimization

Sexual minority youth experience more severe cybervictimization than their heterosexual counterparts (e.g., Garaigordobil & Larrain, 2020). The content of the cybervictimization often focused on their sexual orientation and can involve being outed, which can be dangerous. LGBQ+ youth are more likely to experience online sexual victimization and harassment than their heterosexual peers (Kahle, 2020; Ybarra et al., 2015). They are also at higher risk of online harassment from strangers (Finn, 2004) and cybervictimization through significantly more electronic sources (e.g., by text, multiple social media platforms, multiple apps: Myers et al, 2017). Furthermore, sexual minority youth are at higher risk of polyvictimization (i.e., cyber and offline bullying) than their heterosexual counterparts (Myers et al., 2017).

Prevalence of Cyberbullying Perpetration

Prevalence of cyberbullying perpetration by LGBQ+ youth was reported in only three studies. They found either no difference in prevalence as compared with heterosexual youth (Garaigordobil & Larrain, 2020; Wensley & Campbell, 2012), or higher prevalence of cyberbullying perpetration by LGBQ+ youth (DeSmet et al., 2018). These differences may be due to the smaller proportion of LGBQ+ youth in the latter study (7.1% in DeSmet et al., 2018 vs. 12.5% in Garaigordobil & Larrain, 2020 and 17.2% in Wensley & Campbell, 2012), which may exaggerate differences between cyber-perpetration by LGBQ+ and heterosexual youth. These studies did not specify against whom LGBQ+ youth cyber-perpetrate.

Outcomes Associated with Cybervictimization and Cyber-Perpetration

Sexual minority youth are at higher risk for negative outcomes associated with cybervictimization than their heterosexual peer (studies that examined outcomes n=15). Only one of these studies is longitudinal. In a study examining relationships among minority status and outcomes of cybervictimization and perpetration, sexual minority was the only demographic factor (not gender, ethnic or socioeconomic minority status) to strongly correlate with negative mental health symptoms associated with cyberbullying (Duarte et al., 2018). Severity of outcomes associated with cybervictimization is exacerbated by polyvictimization. For example, gay and bisexual young men who were victimized both by in-person and cyber homophobic bullying had more severe anxiety in early adulthood than those victimized by cyber homophobic bullying alone (Wang et al., 2018). However, more longitudinal research is needed to fully understand long-term impacts.

Sexual minority youth have higher rates of concurrent and long-term mental health outcomes associated with cybervictimization than their heterosexual counterparts. These negative mental health outcomes include depression (Luk et al., 2018; Mereish et al., 2019) and suicidal ideation and attempts (Mereish et al., 2019; Humphries et al., 2021). Based on their 5-year longitudinal study, Luk and colleagues (2018) found that cybervictimization is a significant mediator of depression among sexual minority youth. That is, cybervictimization partially explained the higher level of depression among sexual minority youth as compared with heterosexual youth. Depression associated with cybervictimization can last into early adulthood.

Particular sexual minorities may be at higher risk of mental health challenges related to cybervictimization. For example, in a Canadian study (N=8194), bisexual girls were more likely to report psychological distress, lower self-esteem, and suicidal ideation associated with cyberbullying victimization than gay, lesbian, and questioning youth (Cenat et al., 2015).

Sexual minority youth also have higher rates of concurrent alcohol use (Mereish et al., 2019; Trujillo et al., 2020; Phillips et al., 2017). In a retrospective study with young adults, Li and colleagues (2019) found that higher rates of alcohol use associated with cybervictimization in childhood continue into early adulthood (Li et al., 2019).

Similarly to cybervictimization, cyberbullying perpetration is also positively associated with depression (Garaigordobil & Larrain, 2020).

Risk and Protective Factors

Risk Factors

Table 3 provides a detailed summary of risk factors for cybervictimization and perpetration among LGBQ+ youth. Although these findings are based on limited studies (n=7), and many are identified from only one study (Wang, Hsiao & Yen,, 2019), they provide some insight into the mechanisms that can be potentially targeted by prevention and intervention programs. Despite the limited research, one consistent finding is that in-person sexuality-related victimization (e.g., homophobic, biphobic bullying) is a key risk factor for cybervictimization of LGBQ+ youth.

ModeratorsFootnote 7 |

Direct Effects (Predictors) |

|

|---|---|---|

Cyber Victimization |

Polyvictimization moderates mental health outcomes

|

In-person sexuality-related victimization

|

Low family support

|

||

Obesity

|

||

Early coming out

|

||

Cyber-Perpetration |

Homophobic victimization

|

Protective Factors

Support and connection are key protective factors against cybervictimization and its impacts on LGBQ+ youth. Table 4 provides details of protective factors for cybervictimization among sexual minority youth. These findings should be interpreted cautiously as they are based on single studies and findings that have not been reproduced. There were no studies found that identified protective factors for cyber-perpetration.

Moderators |

Predictors |

|

|---|---|---|

Cyber Victimization |

Family support in childhood

|

In-person support from friends

|

School connectedness

|

Girls and Gender Minority Youth

This section focuses on cyberbullying involving youth minoritized by gender in Canada and abroad, including girls, trans and gender expansive youth.

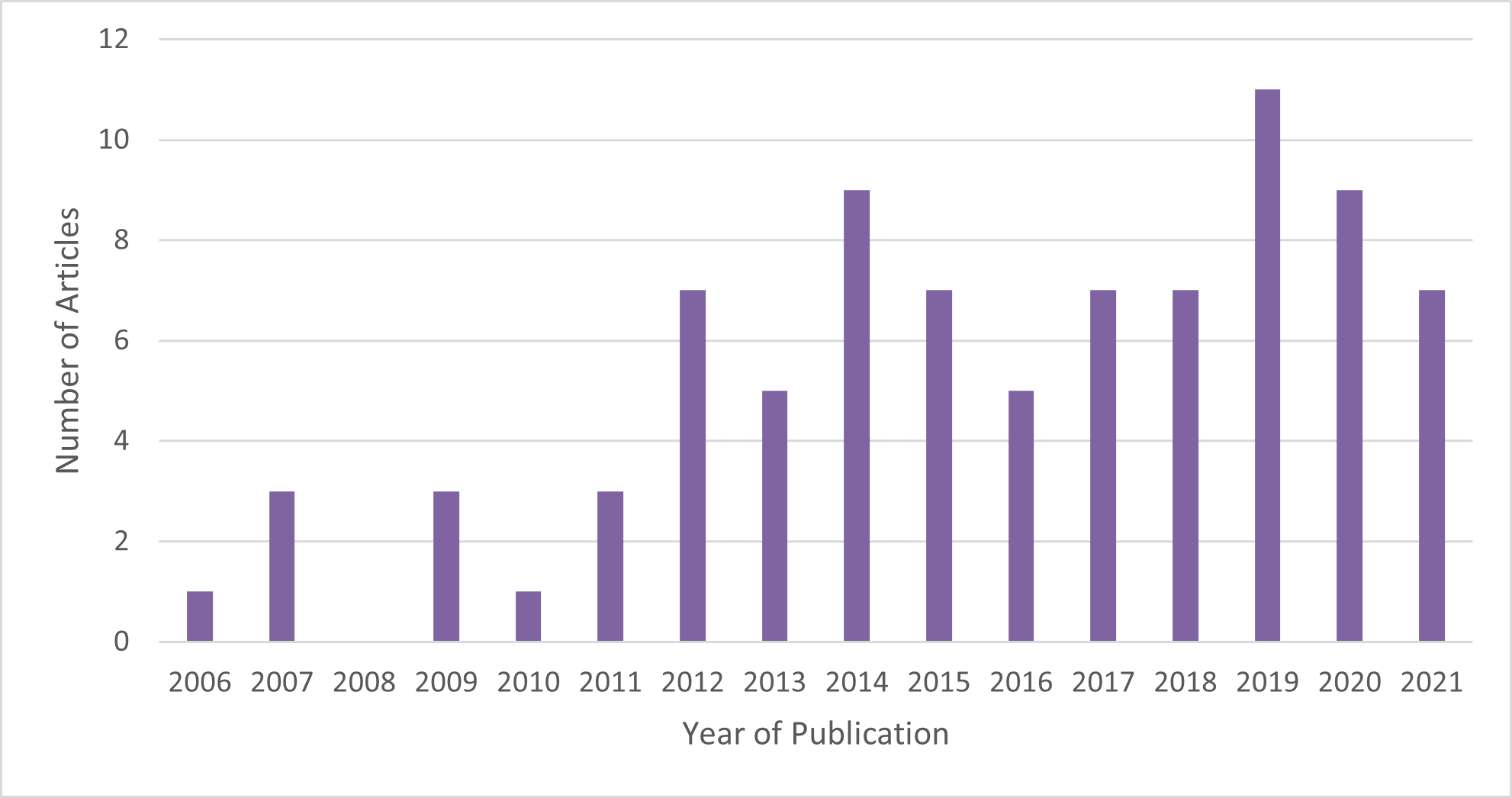

Study Characteristics

A total of eighty-five articles (N=85) included findings related to girls and/or gender minority youth. However, only twenty of these had a specific focus on gender/sex either in the title or research questions. Therefore, most of the gender-based findings are from studies that incidentally report gender-based differences. Trans and gender expansive youth are underrepresented in the literature and disaggregated findings were included in just over 10% of studies included related to girls, trans, and gender expansive youth (n=8).Footnote 8

Most of the studies are quantitative (n=72), seven are mixed methods studies, and four are qualitative. Nine studies were longitudinal. The majority of studies were published in the last ten years. Figure 4 depicts the year of publication for studies focused on cyberbullying experiences of girls, trans and gender expansive youth.

Figure 4: Year of publication of articles related to girls and gender minority youth

Figure 4 – Text version

Year of Publication |

Number of Articles |

|---|---|

2006 |

1 |

2007 |

3 |

2008 |

0 |

2009 |

3 |

2010 |

1 |

2011 |

3 |

2012 |

7 |

2013 |

5 |

2014 |

9 |

2015 |

7 |

2016 |

5 |

2017 |

7 |

2018 |

7 |

2019 |

11 |

2020 |

9 |

2021 |

7 |

Most of these English studies were conducted in Western countries, with the majority of studies from the United States (n=51) and Canada (n=20). There were several from Europe, including three studies from Spain and one each from Finland, Sweden, UK, and Portugal. There were also one each from Israel, Jordan, Japan, Malaysia, Taiwan and Thailand.

Prevalence of Cyberbullying Victimization

There were mixed findings in the literature about the prevalence of cybervictimization for girls and young women. Most of the studies (n=39) found that girls experience more cybervictimization than boys, six found that girls have a lower prevalence of cybervictimization, and five found that prevalence was similar for girls and boys. However, girls are more likely to experience polyvictimization, including cyber-victimization (Ash-Houchen & Lo, 2018; Barboza, 2015; Garnett & Brion-Meisels, 2017). The mixed findings about prevalence are summarized in Table 5.

Although few, studies are consistent that youth who identify as transgender and gender expansive are at higher risk of cybervictimization than their cisgender peers (Eisenberg et al., 2017; Garthe et al., 2021; GLSEN, 2013; Myers et al., 2017; Skierkowski-Foster, 2019; Ybarra et al., 2015). One American study found that transgender youth reported, 2.96, 1.34 and 1.14 times more cyber victimization than cisgender and gender expansive youth, respectively. Gender expansive youth reported, 2.61 and 1.18 times more cyber victimization than male and female youth, respectively (Garthe et al., 2021). An international study (75 countries) found that transgender youth reported more frequent cybervictimization than cisgender, pangender and genderqueer youth (Myers et al., 2017).

Gender Identity |

Higher prevalence (# studies) |

Lower prevalence (# studies) |

Similar prevalence (# studies) |

|---|---|---|---|

Girls/young women |

39 |

6 |

6 |

Trans, gender expansive |

6 |

0 |

0 |

Nature of Cybervictimization

Girls, trans, and gender expansive youth experience specific gendered cybervictimization (e.g., Faucher et al., 2014). For example, girls were more likely to experience “sextortion” online (e.g., humiliation or blackmail using sexualized images: Casado et al., 2019), unwelcome sexualized images or comments (Hazeltine & Hernandez, 2015; Jackson et al., 2009; Mishna et al., 2010), sexual solicitation (Wells & Mitchell, 2013); cyberstalking (Reyns et al., 2012), appearance-related comments (Berne et al., 2014; Jackson et al., 2009), and negative messages about their gender than boys (Jackson et al., 2009).

There was very little included about the nature of cybervictimization experienced by trans and gender expansive youth. However, in one qualitative study, trans and gender expansive youth described cybervictimization related to their gender expression, including cyber-perpetrators asking about their genitalia, misgendering, and making other dehumanizing and transphobic comments (Price et al., 2021). Trans and gender expansive youth are also at greater risk of polyvictimization than their cisgender counterparts (Garnett & Brion-Meisels, 2017).

In a longitudinal qualitative study in Canada, Mishna and colleagues (2020) found that gendered and sexualized cyberbullying were part of a socialization process wherein girls come to expect gender-based violence and inequality. While boys' roles and behaviors in gendered and sexualized cyberbullying were frequently made invisible, girls' experiences were often minimized and normalized by peers, and linked to gender norms and stereotypes that are invisible in their ubiquity (Mishna et al., 2020). These specific characteristics of cybervictimization make visible gender-based root causes influencing cyberbullying that targets girls, trans, and gender expansive youth, although more research is needed to further support this understanding of cybervictimization.

Prevalence of Cyberbullying Perpetration

Similarly, there are mixed findings in the literature about cyberbullying perpetration among girls and young women. Sixteen studies found that boys/young men reported cyber-perpetration more than girls/young women. Five found the opposite and four found no gendered differences. None of the studies described the nature or targets of cyber-perpetration by girls and young women. There were no studies that examined prevalence of perpetration by trans and gender expansive youth.

Outcomes Associated with Cybervictimization

There were mixed findings about whether girls and gender minorities experience more concurrent and long-term (n=2) outcomes associated with cybervictimization. In the majority of studies, girls and young women who experience cybervictimization report more associated negative outcomes than boys and young men (n=14). No studies included outcomes reported by trans or gender expansive youth.

Studies found concurrent and long-term correlates at the individual, social, and system level. At the individual level, there were mixed findings. Most studies found that girls experience more severe mental health and behavioral outcomes. Girls who experienced cybervictimization were more likely to report concurrent and long-term psychological distress (Cénat et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2019; Parris et al., 2020; Sampasa-Kanyinga.& Hamilton, 2015), concurrent and long-term suicidal ideation and attempts (Jackson et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2019; Romero et al., 2018; Sampasa-Kanyinga.& Hamilton, 2015), lower self-esteem and more depression (Berne et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2018; Romero et al., 2018; Tynes et al., 2012) than boys. In one study, girls who were cybervictimized had increased odds of substance use and delinquency (Kim et al., 2019). However, two studies found that mental health outcomes, delinquency and violent behaviors are more pronounced in boys (Alhajji et al., 2019; Mehari et al., 2020).

Two Canadian studies found that girls and young women reported a greater range of negative impacts on academics and their personal lives (e.g., concentration, reputation, ability to make friends) than boys and young men (Faucher et al., 2014; Jackson et al., 2009).

At the system level, in one study, polyvictimization was associated with girls' experiences of the school environment: the number of victimization experiences was significantly associated with a decrease in girls' perception of safety, connection and equity (Garnett & Brion-Meisels, 2017).

Risk and Protective Factors

Very few studies identified risk factors, and no studies included protective factors for cybervictimization for girls and young women. Furthermore, there were none that pertained to trans or gender expansive youth. Table 6 provides a summary of the risk factors that mediate and/or predict cybervictimization. These should be interpreted with caution as they are based on single studies. There were no studies that identified risk or protective factors for cyber-perpetration.

MediatorsFootnote 9 |

Predictors |

|

|---|---|---|

Cyber Victimization |

Depression mediated the association between cybervictimization and suicide attempts for girls only (Bauman et al., 2013) |

Obesity/overweight

|

Disability

|

||

Internalizing symptoms

|

||

Externalizing problems

|

These risk factors suggest that programs that focus on improving mental health may mitigate some of the harms of cybervictimization for girls and young women.

Ethno-Racial Minority Youth

This section focuses on cyberbullying involving young people who are minoritized based on their ethnic and/or racial identity in Canada and abroad. Studies categorized young people minoritized by ethno-racial identity in different ways. In some studies, they were disaggregated by broad ethnic and/or racial categories (e.g., African-American, Black, Hispanic, LatinxFootnote 10, Asian, Arab), while other studies dichotomized the variable (e.g., immigrant and non-immigrant, non-white and white, ethnic minority and ethnic majority).

Overall, the findings vary depending on ethno-racial group, which is indicative of the complexity and heterogeneity of ethno-racial identities and cultures, and various forces of oppression and domination that lead to specific transnational histories and experiences of discrimination. As a result, the findings may reflect the inadequacy of over-simplified ethno-racial minority categories. Moreover, due to the various ethno-racial categories used throughout the studies, much of the findings for specific ethnic and racial groups are based on a small number of articles and should be interpreted with caution.

Study Characteristics

A total of seventy articles (N=70) included findings related to ethno-racial minority youth and fifty of these had an explicit focus in the title or primary research questions about ethno-racial minority youth. Almost all of them are quantitative (n=63), one is qualitative, and six are mixed methods studies. Nine studies were longitudinal.

Figure 5: Year of publication of articles related to ethno-racial minority youth

Figure 5 – Text version

| Year of Publication | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

2008 |

1 |

2009 |

1 |

2010 |

2 |

2011 |

3 |

2012 |

7 |

2013 |

5 |

2014 |

3 |

2015 |

5 |

2016 |

6 |

2017 |

7 |

2018 |

7 |

2019 |

6 |

2020 |

8 |

2021 |

8 |

Most of these studies were conducted in Western countries, including forty-eight from the United States, ten from Canada, and five from Spain. The rest of the studies were from Turkey (n=2) and one each from Cyprus, Finland, Israel, Jordan, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. For a full list of the ethno-racial minorities and majorities studied in each country, please see Appendix A.

Prevalence of Cyberbullying Victimization

Forty-seven studies included findings related to the prevalence of cybervictimization of ethno-racial minorities in comparison with dominant ethno-racial populations, but the findings are mixed. Twenty-five studies found that ethno-racial minority youth experience more cybervictimization than ethno-racial majority populations while fourteen studies found that ethno-racial minority youth experience less. Eight studies found that ethno-racial minority youth experienced a similar amount of cybervictimization as ethno-racial majority youth.

The specific ethno-racial group matters. That is, cybervictimization prevalence varies between ethno-racial minority groups. Most studies were conducted in the United States and these most frequently included Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx youth. Findings for these populations were mixed and the majority of studies found that Black/African-American youth and Hispanic/Latinx youth were less likely to report cybervictimization than white youth (e.g., Angoff & Barnhart, 2021; Ash-Houchen & Lo, 2018; Jackman et al., 2020; Lindsay & Krysik, 2012; Webb et al., 2021; Yousef & Bellamy, 2017).

Alternatively, Asian-American youth experience significantly more cybervictimization than dominant populations and other minorities. While some of these studies occurred before 2020, (e.g., Zalaquett & Chatters, 2014) others capture the increase of anti-Asian cybervictimization since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan (East and Southeast Asian students: Alsawalqa, 2021) and the United States (Chinese-American children and youth: Cheah et al., 2020).

Several studies collapsed ethno-racial groups using dichotomous variables (e.g., immigrant/non-immigrant; ethno-racial minority/ethno-racial majority, white/non-white). Four studies found that immigrant youth (both 1st and, 2nd generation) were more likely to experience cybervictimization than majority youth populations in Europe (e.g., Calmaestra et al., 2020; d'Haenens & Ogan, 2013; Ergin et al., 2021; Strohmeier et al., 2010), while one found lower prevalence of cybervictimization among immigrant youth in Canada (Beran et al., 2015). When combined into a single category of ethno-racial minority, three studies from the United States, Spain, and the UK found ethno-racial minorities more likely to experience cybervictimization (Jones et al., 2013; Llorent et al., 2016; Przybylski, 2019), one study in the United States found that ethno-racial minority youth experience less cybervictimization (Sinclair et al., 2012), and six American studies found no significant differences of cybervictimization prevalence between ethno-racial minority and majority youth (Accordino & Accordino, 2011; Barboza, 2015; Duarte et al., 2018; Lenhart et al., 2011; Morin et al., 2018; Schneider et al., 2012). Due to the use of dichotomous variables, these findings likely obfuscate differences between ethno-racial groups.

Table 7 summarizes the findings by ethno-racial minority and location of the study.

Ethno-racial minority |

Higher prevalence (# studies) |

Lower prevalence (# studies) |

Similar prevalence (# studies) |

|---|---|---|---|

Black/African |

3 (Spain, United States) |

10 (United States) |

0 |

Hispanic/Latinx |

2 (United States) |

9 (United States) |

1 (United States) |

Asian (e.g., Chinese, East, and Southeast Asian) |

5 (Jordan, Spain, United States) |

1 (United States) |

0 |

Indigenous |

2 (Spain) |

0 |

1 (Canada) |

Arab |

2 (Canada, United States) |

1 (Israel) |

0 |

Romani |

2 (Spain) |

0 |

0 |

OtherFootnote 11 |

2 (United States) |

2 (United States) |

0 |

Immigrant |

4 (Finland, Spain, Turkey, Austria, Bulgaria, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands) |

1 (Canada) |

0 |

Ethno-racial minority (dichotomous variable) |

3 (Spain, United Kingdom, United States) |

1 (United States) |

6 (United States) |

Nature of Cybervictimization

While there are mixed findings about the prevalence of cybervictimization among ethnic minority youth, there may be particular characteristics of cybervictimization that differentiate their experiences from those of white or dominant populations. For example, non-white youth were more likely to experience polyvictimization than white youth in the United States (Barboza, 2015; Cantu & Charak, 2020; Weinstein et al., 2021). Non-white youth/emerging adults were significantly more likely to report being victimized by cyberstalking and sexual cyber intimate partner violence (IPV) than their white counterparts in the United States (Cantu & Charak, 2020; Reyns et al., 2012). Immigrant youth were targeted by racist cyberviolence including Islamophobia, and hate speech online (e.g., immigrants from Maghreb, Ecuador and sub-Saharan Africa in Spain: Casado et al., 2019). Furthermore, significantly more youth from ethno-racial minorities report experiencing vicarious racial discrimination online than direct racial discrimination online (Tynes et al., 2008).

Prevalence of Cyberbullying Perpetration

There is much less literature about perpetration by ethno-racial minority youth (14 studies), and the findings are mixed and vary by ethno-racial group: eight studies found higher cyberbullying perpetration among ethno-racial minorities, four found lower cyberbullying perpetration, one found varying results (higher prevalence for one ethno-racial minority and lower prevalence for another), and two found no difference based on ethno-racial identity. The mixed results and small number of studies examining different ethno-racial minorities are insufficient to make conclusions about cyberbullying perpetration prevalence. Table 8 summarizes the findings by ethno-racial minority.

Ethno-racial minority |

Higher prevalence (# studies) |

Lower prevalence (# studies) |

Similar prevalence (# studies) |

|---|---|---|---|

African-American/Black |

3 (United States) |

1 (United States) |

0 |

Romani |

2 (Spain) |

0 |

0 |

Arab |

2 (Israel, United States) |

0 |

0 |

Hispanic/Latinx |

1 (United States) |

1 (United States) |

0 |

Asian |

1 (Spain) |

1 (Canada) |

0 |

Indigenous |

1 (Spain) |

0 |

0 |

Mongolian |

1 (Spain) |

0 |

0 |

OtherFootnote 12 |

0 |

1 (United States |

0 |

Immigrants (first generation) |

1 (Spain) |

1 (Canada) |

1 (Spain) |

Non-white |

2 (Canada, United States) |

0 |

2 (United States) |

Outcomes Associated with Cybervictimization and Cyber-Perpetration

Similarly, findings about ethno-racial minority youth and outcomes of cyberbullying involvement (mainly cybervictimization) varied by ethno-racial group and are based on a small number of studies. Ten studies found higher risk of negative outcomes for ethno-racial minorities, three found no associations between ethno-racial identity and outcomes, and two found lower risk of outcomes associated with cyberbullying involvement as compared with ethno-racial majorities. These studies were from the United States (n=12) and Canada (n=2). Table 9 summarizes these findings by ethno-racial minority.

Ethno-racial minorities who experienced cybervictimization reported more negative mental health than dominant ethno-racial groups. For example, in one study, non-white youth in the United States who experienced cybervictimization scored significantly higher on the suicidal ideation scale than their white counterparts (Hinduja & Patchin, 2010). Vicarious exposure to online racism was also positively associated with psychological distress and perceived stress. Higher levels of vicarious online racial discrimination are associated with poorer mental health among Chinese-American youth (Cheah et al., 2020). In a study in Hawaii, Filipino and Samoan youth were more likely to report feeling badly about themselves as a result of cyberbullying than Native Hawaiian and Caucasian youth (Goebert et al., 2011). In the Canadian context, cyberbullying victimization uniquely contributed to self-reported anxiety and stress among Indigenous adolescents beyond the contribution of traditional bullying victimization, which is a larger contribution than observed in other studies with youth from dominant cultures (Broll et al., 2018).

Parents' experiences of racial discrimination may also play a role in the impacts of cybervictimization on young people. In a study involving Chinese-American youth and their parents, parents' perceptions of being direct victims of racial discrimination online was a risk factor for children's self-reported anxiety and internalizing problems (Cheah et al., 2020).

However, the severity of outcomes may differ between ethno-racial minorities. For example, Hispanic and “other” ethno-racial minorities in the United States who had experienced cybervictimization were more likely to report having a higher, 2-week sadness prevalence and having made a suicide attempt compared with Caucasian and African-American youth (Messias et al., 2014).

Furthermore, outcomes may differ depending on involvement in cybervictimization or cyber perpetration. For example, among Arab-American youth, perpetration predicted physical complaints, whereas victimization predicted psychological distress (Albdour et al., 2019).

Ethno-racial minority |

Higher risk (# studies) |

Lower risk (# studies) |

Similar risk (# studies) |

|---|---|---|---|

Hispanic/Latinx |

4 (United States) |

0 |

0 |

Black/African-American |

1 (United States) |

1 (United States) |

0 |

Indigenous |

2 (Canada, United States) |

0 |

0 |

Asian |

1 (United States) |

0 |

0 |

Arab |

1 (United States) |

0 |

0 |

Immigrant |

1 (United States) |

0 |

0 |

OtherFootnote 13 |

1 (United States) |

0 |

0 |

Multiracial |

1 (United States) |

0 |

0 |

Ethno-racial minority |

3 (United States) |

1 (United States) |

3 (Canada, United States) |

Risk and Protective Factors

There were no consistent findings in the literature about risk and protective factors for ethno-racial minority youth. However, these individual studies, described in more detail in this section offer potential mechanisms that may be able to inform programs to mitigate and prevent cyberbullying with more research

Risk Factors for Cybervictimization

There are several cybervictimization risk factors identified in the literature for ethno-racial minority youth at the individual, social and systems levels. Some are more common for broader categories of ethno-racial minorities, and some are distinctive for specific ethno-racial groups included in these studies. Table 10 summarizes these risk factors.

At the individual level, mental health predicted cybervictimization in specific ways for different ethno-racial groups. For example, low self-esteem and suicidal ideation were predictors for Hispanic-American youth; low self-control was a predictor for Hispanic and African-American youth, and depression was a predictor of cybervictimization for Asian-American youth (Oblad et al., 2017). Similarly, low self-esteem, empathy and social skills predicted cybervictimization for Columbian, Romanian and Spanish students, but not for Moroccan or Ecuadorian students in Spain (Rodriguez-Hidalgo et al., 2018).

Ethnic identity, defined in these studies as exploration, resolution, affirmation and belonging to one's ethnic group(s), is a key moderator of the outcomes associated with cybervictimization. African-American youth who had low levels of ethnic identity and reported more online racial discrimination reported more anxiety (Tynes et al., 2012). Latinx-American youth who had low levels of ethnic identity reported more externalizing problems (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2015).

The purpose of online activity may mediate impacts of cybervictimization on immigrant youth. In a nationally representative longitudinal study in the United States, immigrant youth (first and second generation) experienced pronounced negative influences of cyberbullying in their school on their academic success and sense of school belonging if they frequently used information and communications technology (ICT) for leisure (i.e., online gaming and chatting/surfing online). For immigrant youth who used ICT primarily for information, the adverse effect was not significant and there were no significant effects of ICT use for non-immigrant youth (Kim & Faith, 2020). These findings describe a difference between immigrant and non-immigrant experiences online and a potential targeted context for intervention for immigrant youth (e.g., online gaming and chatting contexts).

Social level risk factors exacerbate the negative impacts associated with cybervictimization for ethno-racial minority youth. In a longitudinal study in the United States, young people's more frequent experiences of offline ethnic-racial discrimination predicted more frequent online ethnic-racial discrimination over time (Lozada et al., 2020). Low levels of school-belongingness strengthened the positive relationships between cybervictimization and depression and anxiety, especially among Latinx youth in the U.S. (Wright & Wachs, 2019).

At social and system levels, unwelcoming environments are risk factors of cybervictimization for immigrant youth. In a study in Turkey, negative peer attitude towards immigrants in their class and school was a risk factor for cybervictimization of immigrant students (Ergin et al., 2021). One nationally-representative Canadian study found pronounced associations of past maltreatment and residence in an unwelcoming neighborhood and cybervictimization among immigrants (but not non-immigrants who reported past maltreatment and living in an unwelcoming neighborhood) (Kenny et al., 2020).

Risk Factors for Cyberbullying Perpetration

Risk factors related to cyber perpetration were rare in the literature. However, there were two studies that highlight predictors. In a longitudinal study in the United States, physical bullying perpetration predicted cyberbullying perpetration among non-Caucasian youth (Barlett & Wright, 2018). The motivation for cyberbullying perpetration differs among ethno-racial minorities: for first generation immigrants in Cyprus, the cyber perpetration is used as a strategy to be accepted and feel affiliated with their peers. This was not a predictor for second-generation immigrants or non-immigrant youth (Solomontos-Kountouri & Strohmeier, 2021).

Moderators |

Predictors |

|

|---|---|---|

Cyber Victimization |

Low school belonging strengthened the positive relationships between cybervictimization and depression and anxiety, especially among Latinx-American youth (Wright & Wachs, 2019) |

Past maltreatment and residence in unwelcoming neighborhood:

|

Low ethnic identity increased the negative impact of online racial discrimination:

|

Low self-esteem:

|

|

ICT used for leisure increased the harms of cybervictimization (i.e., lower academic success and school belonging) among immigrant youth in the U.S. but not for non-immigrant youth (Kim & Faith, 2020) |

Offline bullying victimization:

|

|

Low self-control

|

||

Depression

|

||

Suicidal ideation

|

||

Negative attitude towards immigrants (classroom level)

|

||

Cyber Perpetration |

Low self-control Hispanic and African-American (and Caucasian), but not Asian-American youth (Oblad et al., 2017) |

|

Physical bullying perpetration

|

||

Cyberaggression

|

||

Cyberbullying as a strategy for acceptance and affiliation

|

Protective Factors

There were fewer studies that identified protective factors, which pertain to specific ethno-racial minority groups. For example, African-American young people's ethnic identity and self-esteem mitigated the negative impact of online racial discrimination on anxiety (Tynes et al., 2012). Emotional intelligence mitigated the impacts of cybervictimization on Arab-American young people's self-esteem and academic functioning, but there was no effect for other ethno-racial minority groups (Yousef & Bellamy, 2017).

Friends also may play an important protective role. For example, in a study involving African-American youth, spending more time with friends and talking about their problems was a protective factor against cybervictimization (Cho et al., 2019).

With regards to cyber perpetration, two studies found associations with parental control and monitoring. In a Canadian study, East Asian youth were less likely to engage in cyberbullying. Higher levels of parental control and lower levels of parental solicitation were linked more closely with lowered reported levels of cyber-aggression for East Asian adolescents relative to their peers of European descent (Shapka & Law, 2013). Parents of African-American youth also have a protective effect: fathers' monitoring had a negative association with both cyberbullying perpetration and victimization (Cho et al., 2019).

Moderators |

Predictors |

|

|---|---|---|

Cyber Victimization |

Emotional intelligence mitigated the negative impacts of cybervictimization on self-esteem and academic functioning among Arab American youth, but not among Hispanic or African-American youth (Yousef & Bellamy, 2017) |

Spending time with friends and talking about their problems:

|

Strong ethnic identity:

|

Fathers' monitoring:

|

|

Cyber Perpetration |

Higher levels of parental control and lower levels of parental solicitation:

|

|

Fathers' monitoring:

|

Intersections

Very few studies conduct intersectional analysis to understand the ways in which intersecting systems of oppression and power distinctly shape cyberbullying experiences for minoritized youth living at various intersections of identity. Therefore, there is insufficient research to inform programming. Some findings about the intersections of race, gender, and sexuality and cyberbullying prevalence did emerge, but they are inconsistent likely due to distinctive populations and contexts. These are detailed in the following section.

Ethnicity/Race and Sexuality

Double minoritization (ethnocultural and sexual) is associated with cyberbullying prevalence. In a Spanish study, youth who identified as a “double minority” were more involved in cyberbullying victimization and perpetration than the majority (i.e., heterosexual, white). The difference found between double minority and majority youth was greater than the difference between either sexual or ethnocultural minority and majority youth. Being in a double minority predicted higher levels of cyberbullying victimization and perpetration (Llorent et al., 2016). However, some ethno-racial minority identities may have a protective effect among sexual minority youth. An American study found that bisexual ethno-racial minority youth (Black and Hispanic) had significantly lower odds of cybervictimization compared to white bisexual youth (Angoff & Barnhart, 2021).

Ethnicity/Race and Gender

Ethno-racial identity may affect gendered patterns of cyberbullying prevalence. In a nationally representative sample in Canada, cyber-victimization rates differed significantly by sex among immigrants (2.8% for males vs. 1.4% for females), but not among non-immigrants (Kenny et al., 2020). Conversely, the relationship between gender and cybervictimization was found to be stronger for white students than for students of color in an American study. In other words, cybervictimization was higher for white girls than white boys, whereas for racialized youth, prevalence differed less by gender (Stoll & Block, 2015).

Specific ethno-racial groups have different gendered patterns of cyberbullying prevalence. For example, African-American, Asian, and Hispanic girls were significantly less likely to report being cyberbullied compared with white girls, whereas Asian boys reported more cybervictimization than white boys (Ash-Houchen & Lo, 2018). In a study in Hawaii, there was a significant interaction between gender and ethnicity for cyber-control (i.e., monitoring a dating partner's behavior through electronic forms). Filipino females were more likely to be cyber-controlled via web than Filipino males. Samoan and Caucasian males were more likely to be cyber-controlled via web than Samoan and Caucasian females (Goebert et al., 2011). Finally, an Israeli study found that cultural differences may explain gender differences along ethnic lines. Jewish girls reported more cybervictimization than Jewish boys. There were no gender differences among Arab youth. Conversely, Arab girls reported higher cyber-perpetration than Arab boys, but there were no gender differences in perpetration found among Jewish students. The cultural/ethnic difference was significant among girls, revealing that Jewish girls reported higher cybervictimization than Arab girls, yet Arab girls reported higher cyber-perpetration than Jewish girls. The cultural difference was not significant among boys (Lapidot-Lefler & Hosri, 2016).

Ethnicity/Race, Sexuality, and Gender

Within ethno-racial minority populations, another study found that specific patterns emerge based on gender and sexual minority status: ethno-racial minority boys who identified as sexual minorities, and bisexual ethno-racial minority girls were at higher risk for cybervictimization compared to heterosexual peers of the same ethno-racial identity (Jackman et al., 2020).

Prevention and Intervention Initiatives

The literature search related to minoritized youth found fifteen studies of cyberbullying prevention and intervention initiatives. However, only six articles met the criteria of both evaluating the initiatives and findings relevant to minoritized youth. Only two of the initiatives (Aboriginal e-mentoring BC, and Singularities) are designed for minoritized youth. Initiatives that are not designed for minoritized youth were included if they had any findings about the effectiveness for minoritized youth (e.g., girls, ethnic minority youth). These were all from Western countries (3 in the United States, and 1 each in Canada, Austria and Spain). Five of these studies were longitudinal (ranging from 2 months to 4 years). Table 12 summarizes the programs and impacts on minoritized youth.

Name of Program |

Specific focus on minoritized youth |

Type of treatment |

Program description |

Specific impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Singularities |

Yes |

Individual (online game) |

A web-accessible role-playing game to improve help seeking and coping. Based on 3 theories: 1) Social-cognitive theory, 2) stress and coping theory, and 3) social emotional learning framework. |

Sexual and gender minority youth in the intervention experienced greater reductions of cybervictimization than control participants. |

Aboriginal e-mentoring BC |

Yes |

Individual (mentorship) |

An online mentorship program to connect Aboriginal youth with mentors in postsecondary health sciences programs. The program focuses on goal setting, internet safety, study habits and career goals. |

Aboriginal youth learned awareness of online safety and prevention and coping skills (no findings about cybervictimization or cyber-perpetration). |

The ConRed cyberbullying prevention program |

No |

Whole school |

A school community program with four strategies: 1) proactive policies, procedures and practices, 2) school community competencies, 3) protective school environment, 4) school-family-community partnerships. Based on Normative social behavior theory (injunctive norms, social expectations, and group identity processes). |

Drop in cybervictimization, but less for girls than boys. No drop in cyber-perpetration or increase in feeling safe in the school among girls. |

Dating Matters comprehensive teen dating violence prevention model |

No |

Whole school |

A program that promotes respectful relationships and prevents risk behaviors using multiple components at the individual, relationship, and community levels. |

Significant program effect for girls (reduction of risk for cyber-perpetration and cybervictimization). |

Olweus bullying prevention program |

No |

Whole school |

Adults in the school show interest, set limits, use consistent consequences and act as positive role models. |

Program effects (reduction in cybervictimization and cyber-perpetration) were less for girls than boys and similar for Black and white youth. |

ViSC social competence program |

No |

Whole school |

The program's effective components include teacher trainings, parent meetings, and several components for teachers and students. |

Intervention was effective independently of gender and ethnicity. |

There are a few key takeaways from the examination of literature about cyberbullying prevention and intervention initiatives and minoritized youth.

- There is a lack of programs focused on minoritized youth. Only two programs were found in the academic literature, and only one of these has a cyberbullying focus or demonstrated efficacy in addressing cybervictimization. Interestingly, both of these initiatives are focused one-on-one (individual treatment) rather than group-based initiatives.

- Whole school programs that are intended for diverse youth may or may not be as effective for minoritized youth. There are not enough studies to understand their effects on different populations.

- There is insufficient information to identify effective program components for sexual, gender and ethno-racial minority youth.

A detailed table of these initiatives and programs is included in Appendix B.

Conclusion

Key Takeaways

This report focussed on the recent literature about cyberbullying in youth who are minoritized based on their gender, sexuality and/or ethno-racial identities. However, a caveat to this report is that each of these categories and the way they are delineated in research are provisional and often shaped by a dominant Western (i.e., white, heteropatriarchal, cisnormative, colonial) imagination of “other”. This imagination collapses the heterogeneity of complex populations defined more by their minoritization rather than their strengths and specificities. It is problematic to assume similar experiences within or between these minoritized populations. At best, these provisional categories erase specific experiences of discrimination and ignore meaningful differences.

However, there is one common theme across all of these populations: minoritized youth are at greater risk of polyvictimization. That is, youth minoritized based on gender, sexuality and ethno-racial identity are more likely than their societally privileged counterparts (i.e., white, heterosexual, cisgender boys) to be targeted for both offline and online cybervictimization (Ash-Houchen & Lo, 2018; Barboza, 2015; Cantu & Charak, 2020; Garnett & Brion-Meisels, 2017; Myers et al., 2017; Weinstein et al., 2021). Polyvictimization heightens the risk for negative outcomes and increases the risk of more frequent and future cybervictimization (e.g., Cho et al, 2019; Duong & Bradshaw, 2014; Lozada et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2018; Weinstein et al., 2021). Therefore, interventions that reduce the risk of offline bullying may have the added benefit of reducing the risk of simultaneous and persistent cybervictimization (Weinstein et al., 2021).

In general, the research about cyberbullying experiences of minoritized youth is a recent and newly emerging area of study. As a result, there are limited studies on risk and protective factors and even fewer intervention studies to inform cyberbullying prevention and intervention initiatives for gender, sexual and ethno-racial minority youth. Common and specific risk and protective factors can serve to identify mechanisms to be targeted by prevention and intervention programs, but more research is needed to further identify and understand possible mechanisms.

LGBQ+ Youth

Based on the consistently higher risk of cybervictimization and negative outcomes in the literature in comparison to heterosexual youth, cyberbullying targeting LGBQ+ youth should be a priority focus of cyberbullying prevention programs.