Methods of Preventing Corruption: A Review and Analysis of Select Approaches

By: Bradley Sauve, Jessica Woodley, Natalie J. Jones, & Seena Akhtari

Report number: 2023-R010

Authors Note

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Public Safety Canada. Correspondence concerning this report should be addressed to:

Public Safety Canada, Research Division

340 Laurier Avenue West

Ottawa ON K1A 0P8

Canada

PS.CPBResearch-RechercheSPC.SP@ps-sp.gc.ca

Abstract

Given the vast number of social and economic impacts of corruption, combined with Canada's declining score on the Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions IndexFootnote 1 (equating to increased perceptions of corruption within Canada), preventing corruption has become an increasingly important topic. This literature review provides a comprehensive summary of methods commonly used to prevent corruption in both the private and public sectors and where possible, provides insight on which preventative methods have empirical value and demonstrated effectiveness. Four main approaches to preventing corruption are highlighted: (1) value-based approaches; (2) compliance-based approaches; (3) risk management approaches; and (4) awareness and participation-based approaches. Within these four approaches, 18 specific corruption prevention methods are examined and assessed. Findings demonstrate wide variability in the empirical effectiveness of existing prevention methods. Analysis of the findings demonstrates that organizations should seek to develop compliance programs and anti-corruption strategies that (1) involve multiple evidence-based methods; and (2) tailor prevention methods to meet the specific needs and context of the organization. Due to limitations of the extant literature, the current research cannot ascertain the specific degree to which each prevention method can reduce corruption. Moreover, many of the prevention methods offered in this review have only shown effectiveness in preventing certain forms of corruption and as such, effectiveness should not be generalized across contexts. A number of possible avenues for future research are proposed, including the need to examine the compound effect of employing multiple prevention methods simultaneously.

Introduction

Corruption can encompass a variety of different criminal acts with varying degrees of severity. While there exists no universal definition of corruption, the most commonly applied definition considers it to be “the abuse of public or private office for personal gain” (Transparency International, 2021b, para 1).Footnote 2 This broad definition of corruption encompasses a variety of different acts including but not limited to the misuse of public funds, the acceptance of bribes, bid-fixing, embezzlement, collusion, extortion, or influence peddling. Corruption can occur in a variety of different settings. For example, border or immigration officials could accept bribes and gratuities in return for allowing certain products to be trafficked (Federal Bureau of Investigation [FBI], 2022). Another scenario could involve city officials accepting bribes or kickbacksFootnote 3 in exchange for awarding public contracts (Chaster, 2018). A third and perhaps less severe form of corruption could simply involve giving unfair or preferential treatment to some individuals at the expense of others (i.e., favouritism, nepotism, cronyism, or clientelism) (United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime [UNODC], 2019). Certain scholars and corruption agencies have chosen to further differentiate between styles of corruption, noting that there are stark differences between petty corruption, grand corruption, and political corruption (see Table 1 for definitions). Its specific form notwithstanding, corruption in both the public and private sectors can, among other outcomes, lead to increases in business costs, disguise or facilitate criminal activity, lead to the misallocation of public resources, influence policy outcomes, weaken public confidence in government, reduce economic development, and generate profits for organized crime (OC).

Category of corruption |

Definition |

|---|---|

Petty corruption |

“Everyday abuse of entrusted power by public officials in their interactions with ordinary citizens, who often are trying to access basic goods or services in places like hospitals, schools, police departments and other agencies” (Transparency International, 2022a) |

Grand corruption |

“The abuse of high-level power that benefits the few at the expense of the many, and causes serious and widespread harm to individuals and society” (Transparency International, 2022a) |

Political corruption |

“Manipulation of policies, institutions and rules of procedure in the allocation of resources and financing by political decision makers, who abuse their position to sustain their power, status and wealth” (Transparency International, 2022a) |

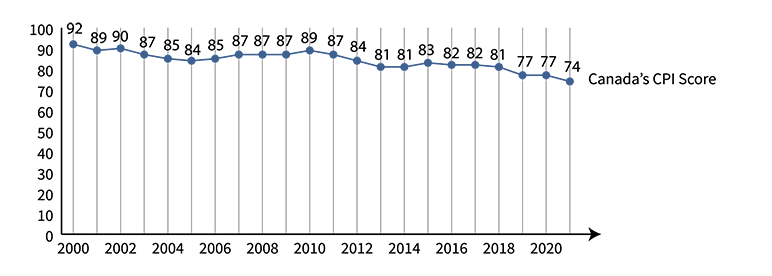

Based on the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), Transparency InternationalFootnote 4 has typically determined Canada to have relatively low levels of corruption (Canada currently ranks 13th out of 180 countries with a score of 74/100).Footnote 5 However, Canada's favourable ranking on the CPI notwithstanding, the country has experienced a relatively consistent drop in its score over the past two decades, indicating increasing perceptions of corruption (see Figure 1). Transparency International (2022d) attributes this drop in score to the presence of major political scandals, concern surrounding money laundering taking place in Canada, criticism from international organizations regarding Canadian whistleblower protections, and outdated access to information legislation. Given Canada's declining score on the CPI, coupled with the vast number of social and economic impacts of corruption, devising and implementing measures to prevent corruption has become an increasingly important topic.

Figure 1: Corruption perceptions index – Canada's score

Image description

Line graph showing Canada's score on the Corruption Perception's Index from 2000 to 2021. There was a steady downward trend in Canada's score, with the score peaking at 92 in 2000 and gradually declining to 74 in 2021. There was a slight uptick in the trend in 2010, where Canada's score reached 89, before it continued its trend downwards. Full data are available below.

Note: Data for this figure was taken from Transparency International's (2022b) Corruption Perception Index.

| Year | Canada's CPI Score |

|---|---|

| 2000 | 92 |

| 2001 | 89 |

| 2002 | 90 |

| 2003 | 87 |

| 2004 | 85 |

| 2005 | 84 |

| 2006 | 85 |

| 2007 | 87 |

| 2008 | 87 |

| 2009 | 87 |

| 2010 | 89 |

| 2011 | 87 |

| 2012 | 84 |

| 2013 | 81 |

| 2014 | 81 |

| 2015 | 83 |

| 2016 | 82 |

| 2017 | 82 |

| 2018 | 81 |

| 2019 | 77 |

| 2020 | 77 |

| 2021 | 74 |

This report seeks to review and describe methods commonly used to prevent corruption both within Canada and globally. Specifically, the purpose of this review is to provide a comprehensive summary of methods commonly used to prevent corruption in both the private and public sectors and where possible, provide insight on which preventative methods have empirical value and demonstrated effectiveness. The first section of this report will describe the methodology applied to compile the relevant literature. The second section will detail, analyze, and synthesize the findings of the literature review. The third section will discuss the research findings and attempt to situate them within a broader policy context. The fourth section offers a brief summary of the research and offers some concluding thoughts. The fifth and final section of this report will highlight the limitations of the research findings before presenting some potential avenues for future research.

Methodology

This report broadly reviews publicly available empirical literature pertaining to methods of preventing corruption in both the private and public sectors. This review draws on a variety of sources including the academic and grey literature as well as governmental and organizational reports. When considering the effectiveness of the proposed prevention methods, this review places the majority of its focus on empirical research, while also drawing upon theoretical and policy evaluation work in order to contextualize and explain results. While literature specific to the Canadian context is prioritized and underscored, international literature on methods of preventing corruption are also included.

Google Scholar was used as the primary search engine in collecting articles for this review. Furthermore, the search of the literature was constrained to English language articles that were published between January 2000-February 2022. The following search terms were used in various combinations: prevention, corruption, effect, compliance, program, code of conduct, value-based, four-eyes principle, ethics training, intrinsic motivation, organizational culture, anti-corruption, compliance-based, extrinsic motivation, wages, merit-based, promotion, penalty, punishment, fine, law, sentence, reporting channels, whistleblowing, risk assessment, top-down, bottom-up, audit, due diligence, conflict of interest, asset-disclosure, position rotation, recruitment, awareness, educational, campaign, transparency, press freedom, participation, e-government, freedom of information, and access to information. Screening of references (i.e., snowballing) as well as reverse snowballing using the google scholar “Cited by” function was also completed. Following the search and an initial screening of abstracts, 193 articles were deemed to meet inclusion criteria. Upon further analysis of the 193 sources, 47 were excluded due to their lack of relevance for the current study and an additional 16 were deemed unnecessary to incorporate into the final review. Studies excluded for the latter reasoning were solely non-empirical studies that were not required for contextualization purposes. A final number of 130 articles were incorporated into the final draft.

Methods of preventing corruption

Incidents of corruption have been found in various societal spheres, from the public procurement process (Charbonneau, 2015; Chaster, 2018), to humanitarian operations (Transparency International, 2014), and even in professional sports (Department of Justice, 2015). The link between corruption and organized crime (OC) has been well established both operationally and empirically (CISC, 2021; European Commission et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2020). Thus, the prevention of corruption is crucial to both ensuring the integrity of private and public systems, as well as in reducing the opportunity for OC involvement. Recent research has proposed a number of methods that are aimed at preventing corruption in both the public and private sectors. For organizational purposes, these methods have been classified under four overarching themes: (1) value-based approaches; (2) compliance-based approaches; (3) risk management approaches; and (4) awareness and participation-based approaches. Each of these themes and the specific methods that fall under them will be examined in detail below.

Value-based approaches

Value-based approaches to preventing corruption are relatively new and operate on the premise that creating an environment that promotes ethical behaviour, accountability and integrity amongst employees is more effective than implementing strict rules and guidelines that force employees to act ethically through threat of punishment or fear of reprisal. Value-based approaches follow the premise that corruption can be prevented by instilling, institutionalizing, and internalizing appropriate moral values, as doing so is expected to ultimately decrease one's desire to engage in corrupt acts (Gong & Yang, 2019). Four different prevention methods fall under this theme: (1) the tone at the top principle; (2) training programs; (3) intrinsic motivations; and (4) changing organizational culture.

Tone at the top principle

The tone at the top principle emphasizes the importance of having strong anti-corruption values at the top of an organization (i.e., senior level management) as the views and actions of leaders and executives are key in influencing the motivations and actions of employees. Essentially, organizational culture starts at the top; therefore, if senior level management strongly denounces corruption, so too will lower-level employees (Lambsdorff, 2015). Fundamentally, this principle is grounded in elements of behavioural modeling, which has been well established in the fields of behavioural and social psychology (Bandura, 1997; Walumbwa et al., 2010).

Various prominent anti-corruption bodies have advocated for the importance of having a strong tone from the top. For example, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) emphasizes the importance of strong leadership and demonstrating commitment to anti-corruption at the highest levels of an organization (OECD, 2017). Transparency International (2022c) argues that in order to prevent corruption, organizations need to create a corporate culture that fosters integrity and ethical behaviour. They note that a key contributing factor to creating such an environment is through a strong tone from the top. Additionally, the 30th recommendation in the Charbonneau InquiryFootnote 6 recommends having proper ethics training specifically for directors of professional orders as individuals in these positions can play a crucial role in the governance of organizations and the protection of the public (Charbonneau, 2015).

In empirically studying the effectiveness of the tone at the top principle in the context of corruption, researchers have used a variety of methodologies such as interviews (Six et al., 2012) and web-based surveys (Bussmann & Niemeczek, 2019). However, much of the empirical evidence in support of the tone at the top principle comes from experimental and laboratory study designs, which can lack a degree of external validity (i.e., applicability to real-word settings). This methodological limitation notwithstanding, the majority of research examining the tone at the top principle has been positive (Boly, 2019; d'Adda et al., 2014; Thaler & Helmig, 2015). For instance, Boly et al. (2019), in their experimental study involving a framed embezzlement scenario, found evidence demonstrating the existence of a legitimacy effect, whereby policies originating from a corrupt official were less effective than those created by an honest official. Specifically, the research team found that policies increasing the probability of detection can significantly deter actors from engaging in embezzlement, but only when these policies are implemented by an official who is perceived as “clean” or corruption-free. The presence of this legitimacy effect points towards the importance of fostering an honest ethic, especially among top-ranked officials (Boly et al., 2019).

While there is some empirical evidence supporting the use of the tone at the top principle, Lambsdorff (2015) notes that it is a very difficult phenomena to objectively study, especially in a real-world scenario. As indicated above, much of the research on the tone at the top principle has been experimental in nature and thus, may lack a degree of external validity. That being said, there is no compelling evidence to suggest that this method is ineffective or counter-productive. Therefore, establishing a strong ethical tone at the top may be a useful tactic for organizations to implement in an effort to prevent corruption. Although there is insufficient evidence to determine the degree to which this method could prevent corruption on its own, there does exist empirical support for its underlying social and behavioural mechanisms (Bandura, 1997; Walumbwa et al., 2010).

Training programs

Ethics training programs are typically offered by organizations to their employees and involve promoting personal standards, professional responsibility, and providing guidance to employees on how they should conduct themselves in relation to organizational standards and when presented with ethical dilemmas. Boehm and Nell, (2006) in writing on behalf of the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, note that in relation to corruption, the purpose of such trainings is twofold: firstly, ethics and anti-corruption training is intended to provide trainees with a deeper understanding of the intricacies of corruption and afford them the necessary education and abilities to recognize it. Secondly, such training intends to provide trainees with hands-on skills on how to address corruption should they be confronted with it.

Many prominent anti-corruption organizations view ethics training and anti-corruption training as a common best practice. For example, Transparency International (2022c) highlights that employees should not only be trained on their company's code of conduct but that they should also receive anti-corruption training specific to their role (especially those in high-risk areas such as procurement). In turn, the OECD recommends organizations provide adequate training for employees on conflicts of interest, company policies, codes of conduct, and high-risk situations (OECD, 2017). Notably, the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) Footnote 7 places significant emphasis on the importance of training programs as methods of prevention.Footnote 8

There is a substantial body of empirical research examining the effectiveness of ethics training in various spheres (Steele et al., 2016). However, there is currently a lack of research examining its effectiveness in reducing corruption specifically. That being said, while research has not necessarily demonstrated that ethics training is effective in preventing corruption directly, a number of studies have demonstrated its ability to prevent certain contributing factors or facilitators of corruption (Hauser, 2019; Kaptein, 2015; May & Luth, 2013; Mumford et al., 2008). For example, Hauser (2019), through regression analysis, found that business professionals who receive anti-corruption training are significantly less likely than their untrained counterparts to justify corrupt behaviour, thus demonstrating that anti-corruption training can be effective in suppressing the psychological antecedents of corruption. Moreover, Kaptein (2015), in analyzing survey results from adults working in large US organizations, found that unethical behaviourFootnote 9 occurs less frequently in organizations that have ethics training programs in place. Specifically, the results of this regression analysis demonstrated a direct negative relationship between the provision of ethics training and the endorsement of unethical behaviour. Ethics training in academic contexts has also demonstrated effectiveness in improving perspective-taking, moral efficacy (i.e., confidence in dealing with ethical dilemmas), moral courage (i.e., willingness to bring forward ethical dilemmas), and overall efficacy in rendering ethically-grounded decisions (May & Luth, 2013; Mumford et al., 2008).

In general, empirical research has demonstrated that ethics training programs can produce a number of positive effects that can help lead to the prevention of corruption. However, it is important to acknowledge that this literature review has examined ethics training and its effectiveness quite broadly. As such, it is important to note, as demonstrated by the findings of Harkrider and colleagues (2013), the effectiveness of ethics training can be dependent on various aspects of the specific training model and structure. For instance, these researchers found that case-based ethics instruction that imposes a high degree of structure (though the use of prompt questions) can increase training effectiveness. A similar point has also been emphasized by Boehm and Nell (2006), who acknowledge that not all anti-corruption or ethics training is the same and effectiveness can change greatly depending on the target group (e.g., public sector, private sector, academia, or media) and other contextual factors (e.g., training instruments used, course design, time and cost dedicated). Therefore, results should be interpreted with these caveats in mind.

Intrinsic motivation

Building intrinsic motivation to prevent corruption is based on the principle that the internal or psychological satisfaction of abstaining from corruption can be greater than the external rewards that result from engaging in it. Therefore, in practice, fostering intrinsic motivation involves instilling values into employees so that they are motivated to act ethically and in accordance with their codes of conduct regardless of any external rewards.

Transparency International has advocated for the promotion of intrinsic motivation, emphasizing that there is a real emotional reward that comes from doing something “right” for others (Zúñiga, 2018). Furthermore, numerous research studies across various disciplines have demonstrated the important positive impacts of intrinsic motivation on performance outcomes (Fishbach & Woolley, 2022). However, the empirical research on the efficacy of promoting intrinsic motivation in the context of preventing corruption has not been entirely supportive. Namely, Abbink and Hennig-Schmidt (2006) and Abbink et al. (2002), via a set of experimental laboratory studies, found that establishing intrinsic motivation was ineffective in reducing corruption given that participants were unconcerned with the negative results of their actions (i.e., negative externalities had no effect on corruption levels). However, in contrast to the findings of Abbink and Hennig-Schmidt and Abbink et al., Barr and Serra (2009) conducted an experimental study indicating that the negative framing of a corruption scenario does indeed have an effect on the likelihood of participants engaging in corruption. Specifically, they found that the presence of higher negative externalities (i.e., perceived external consequences) was associated with lower levels of corruption, thus signaling the potential effectiveness of building intrinsic motivation in the context of thwarting corruption.

Outside of experimental studies, which lack a degree of external validity, correlational and cross-sectional research has also demonstrated an inverse association between intrinsic motivation and levels of corruption. For example, Cowley and Smith (2014), in comparing measures of intrinsic motivation (measured using select data from the World Values Survey) to a country's level of perceived corruption (measured using CPI data), were able to demonstrate a significant negative relationship between the level of intrinsic motivation among public sector employees and the country's perceived level of corruption. In other words, a country that has high levels of corruption also has low levels of intrinsic motivation among public sector employees. Additionally, Kwon (2014) provides individual-level microdata from his study of Korean public servants demonstrating that those who find their jobs intrinsically interesting or satisfying have a lower tolerance towards corruption.

A smaller body of empirical literature has focused on examining different factors and conditions that can influence the effectiveness of intrinsic motivation reducing potential for corruption. Namely, this research has focused on the possibility of a “crowding out” or “over-justification” effect, whereby external incentives for abstaining from corruption lead to an erosion of employee intrinsic motivation, which in turn, can lead to increases in corruption. Empirical studies have demonstrated that numerous factors can lead to a crowding out effect, including combining salary bonuses with penalty schemes (Armantier & Boly, 2014), increasing employee wages (Dhillon et al., 2017), increasing surveillance and monitoring (Schultze & Frank, 2003) and over-emphasizing financial benefits (Van der Linden, 2015). However, there is insufficient evidence to determine the net effect of crowding out intrinsic motivations on corruption levels. Additionally, although in theory, crowding out or eliminating intrinsic motivation can lead to higher levels of corruption, these relationships have yet to be demonstrated empirically.

Overall, empirical evidence surrounding the effectiveness of intrinsic motivation as a method of preventing corruption is generally positive. However, some key experimental studies still find intrinsic motivation to play only a minimal role. Notably, caution should be exercised when relying on intrinsic motivation to prevent corruption due to the possibility of other methods crowding out or even reversing its positive effects.

Changing organizational culture

A more passive or indirect means of preventing corruption is to focus on creating a high-level cultural change within an organization. This method is premised on the notion that employees will adopt whatever values are present in the organization they join. Therefore, an organization that promotes values associated with anti-corruption will instill these values in their employees (Treviño et al., 2006). This is distinct from the tone at the top principle, which focuses solely on the importance of ethical leadership. However, as mentioned above, the presence of ethical leadership could likely influence a change of culture across an organization as the actions of leaders and executives are key in influencing the actions of employees.

Campbell and Goritz (2014) conducted a series of interviews with subject matter experts (SMEs) regarding their experiences with corruption and found that corrupt organizations tend to emphasize values such as success, results, and performance, which can lead to an organizational mentality that assumes “the end justifies the means” (Campbell & Goritz, 2014, p. 291). In contrast, an organization, sector, or business can focus on improving its reputation and culture through the creation of policies and practices that emphasize values such as accessibility, participation, monitoring, oversight, accountability, compliance, and cooperation. However, it should be noted that changing organizational culture involves more than simply implementing internal policies and guidelines; rather, it involves completely disrupting any problematic organizational operations (Hodges & Steinholtz, 2017). Finally, while the assumptions surrounding this approach are similar to that of the tone at the top principle (i.e., employees will adopt the values present in the organization), an important distinction is that this approach focuses on a more holistic reputational and cultural change, whereas the tone at the top approach focuses solely on the importance of ethical leadership.

The importance of improving or changing organizational culture has been advocated by many anti-corruption bodies. The Charbonneau Inquiry, in its 54th recommendation, emphasizes the importance of developing a culture of integrity in order to aid in the prevention of corruption. Furthermore, the UNCAC in Article 8(1) states that in order to fight corruption, signatories need to promote values such as integrity, honesty, and responsibility amongst members of the public service. Finally, the OECD recommends creating an organizational culture that emphasizes values such as transparency, meritocracy, professionalism, fairness, and accountability and denounces nepotism, favouritism, and abuse of power (OECD, 2017).

While the effect of changing organizational culture is difficult to empirically study, some research does in fact support the approach (Bussmann & Niemeczek, 2019). For example, Bussman et al. (2021) conducted a multivariate analysis of cross-cultural survey data on crime prevention and found that integrity-promoting company cultures were crucial for the success of compliance management systems.Footnote 10 Additionally, other studies, while not directly demonstrating the empirical effectiveness of this approach, have shown that the presence or perceived presence of corruption in an organization can lead to further increases in corruption levels (i.e., the contagion effect) (Abbink et al., 2018; Boly et al., 2019; Schram et al., 2022). Namely, Schram and colleagues (2022), in their laboratory experiment involving individuals from the Netherlands, Russia, Italy, and China found there to be an increase in bribery when actors were able to observe other actors engaging in bribery. Furthermore, Boly et al. (2019), in their experimental study of embezzlement scenarios, found that when one official is dealing with another corrupt official, their likelihood of the former engaging in embezzlement increases. Similarly, Abbink et al. (2018), in their experimental study, found that when participants perceived the group they were interacting with to be corrupt, they were twice as likely to offer bribes. Collectively, the findings of these studies demonstrate that an observable presence of corruption in an organization increases the likelihood that organizational actors will engage in corruption. Therefore, fostering an organizational culture that promotes and instills anti-corruption values could prove to be an effective means of preventing corruption by decreasing the perception that an organization is corrupt.

In theory, the idea of creating an organizational culture that fosters strong ethical values is likely an essential first step towards countering corruption. As demonstrated above, the importance of creating such a culture has been advocated by various anti-corruption bodies and scholars. Additionally, there is a moderate degree of empirical evidence that supports – even in an indirect fashion – the relationship between organizational culture and corruption. Furthermore, the psychological mechanism underlying this approach (i.e., the likelihood individuals will assimilate or adopt the views of their group) has received ample empirical support in the field of social psychology (Asch, 1951; Kelman, 1958; Son et al., 2019). However, it should be noted that altering an organization's culture is a difficult undertaking and as such, this approach can require substantial time and resources (Langevoort, 2017; Sööt, 2012; Webb, 2012).

Compliance-based approaches

Compliance-based approaches seek to prevent corruption and misconduct through the implementation and enforcement of a set of rules, laws, or guidelines. Under this approach, employees are thought to abstain from corruption in order to obtain desired rewards and avoid punishment. For the most part, methods under this approach are based on the premise that corruption is the result of a cost-benefit conducted by the actors involved (Becker, 1968). Essentially, those engaging in corruption weigh the costs of engaging in corrupt acts (e.g., facing punishments or loss of extrinsic rewards) against the possible benefits (e.g., monetary rewards or personal favours). Therefore, the logical solution to this problem would be to either increase the costs or reduce the benefits associated with acts of corruption. Compliance-based methods take the former approach and seek to prevent corruption though increasing the costs of engaging in such acts. Two different methods fall under this category: (1) extrinsic motivations and (2) penalties and punishments.

Extrinsic motivations

Extrinsic motivations are external rewards intended to motivate employees to act ethically and abstain from corruption. The most common form of extrinsic motivation examined in the literature is the use of monetary incentives (i.e., higher wages or wage increases). From a theoretical standpoint, raising employee wages is believed to lower corruption levels for two main reasons. Firstly, it increases the costs associated with engaging in acts of corruption as employees face the potential to lose substantial income. Secondly, raising employee wages decreases the need for employees to engage in corruption as they are already being adequately compensated.

The UNCAC in Article 7(1c) advocates for the importance of adequate remuneration and equitable pay scales (specifically in the public service), arguing that these elements can help to reduce the likelihood of employees engaging in corruption. Other anti-corruption bodies have also encouraged the adoption of variations on this approach. For example, Transparency International (2022c) recommends specifically linking renumeration incentives and bonuses to anti-corruption performance, as opposed to the traditional linking of incentives to various results-based indicators (e.g., increased company revenue).

Empirical research examining the effectiveness of wage increases in preventing corruption is mixed. A number of experimental laboratory studies have found wage increases to be an effective means of preventing corruption (Armantier & Boly, 2011; Azfar & Nelson, 2007; Barr et al., 2009). For example, in their experimental study involving Ethiopian nursing students, Barr et al. (2009) found that those who receive higher wages are less likely to engage in embezzlement scenarios. Furthermore, in a combined laboratory and field experiment investigating exam-grading practices, Armantier and Boly (2011) found that higher paid graders were less likely to accept bribes from students. International studies have also provided evidence pointing towards the effectiveness of increasing employee wages. For example, Cornell and Sundell (2020) conducted a cross-country comparison using public service wage information from the International Labour Organization, as well as corruption information from Transparency International's Global Corruption Barometer. The researchers found a significant negative relationship between wages and levels of corruption (i.e., higher wages were associated with lower levels of corruption).

Despite these promising results, other empirical studies have demonstrated that wage increases have little to no effect on corruption (Abbink, 2005; Alt & Lassen, 2014). For example, Dahlström et al. (2012), in conducting a macro-level cross-sectional study using a combination of data from the World Bank Governance Indicator and surveys with SMEs, demonstrate that higher government wages do not have a significant impact on lowering levels of corruption. Furthermore, other research has actually pointed towards a positive correlation between wage increases and corruption (Navot et al., 2016; Sosa, 2004). For example, based on data from the World Values Survey, Navot et al. (2016) reported that higher public service wages increase one's propensity to tolerate corruption and thus, lead to higher corruption levels. Svensson (2005) supports this notion with a theoretical argument that higher wages provide bribees with more bargaining power, hence facilitating bribes of higher value.

Other studies have noted that the effectiveness of extrinsic motivations may be influenced by various contextual factors (Abbink & Serra, 2012; Svensson, 2005). For example, Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (2021), in their study on the effects of public sector wages on corruption levels, find that in countries with low public-private wage differentials (i.e., public sector and private sector employees make similar wages) increasing the wages of public servants is indeed effective in reducing corruption. However, in countries where there is a substantial wage inequality between the public and private sectors, raising the wages of public officials actually increases corruption levels. Hence, wage inequality moderates the relationship between extrinsic motivations (via wage increases) and corruption. Additionally, findings from a cross-country analysis carried out by An and Kweon (2017) demonstrated that public-sector wage increases are more effective in non-OECD countries (which typically have higher levels of corruption) and in countries that have low government wages. Another notable finding comes from a study carried out by Van Rijckegham and Wedner (2001) who, after controlling for several variables including the probability of detection, penalty rates, and governmentally imposed economic controls, found a statistically significant negative relationship between civil-service pay and corruption. However, results from their study indicate that large increases in civil service wages would be required to reduce corruption on its own. Therefore, while adequate civil service wages may be one method used to help prevent corruption, this approach should be part of a multipronged strategy.

More broadly and outside of the context of corruption, research in the field of behavioural psychology has also indicated that while extrinsic motivation can lead to positive behavioural change, such changes may be short-lived. For example, Princeton University held a Doing-in-the-Dark campaign where students competed in their ability to reduce energy consumption for one month. In studying this campaign, Van der Linden (2015) found that the competition did indeed reduce student consumption. However, following the competition, energy consumption returned to pre-competition levels.

The mixed empirical evidence on the effectiveness of employing wage increases to prevent corruption (e.g., Meyer-Sahling et al., 2018) suggests that while extrinsic rewards through wage increases can be one strategy to mitigate corruption, it is not one that should not be applied indiscriminately or on its own (note that a sole reliance on wage increases to prevent corruption could be incredibly costly). In using wage increases to prevent corruption (ideally as part of a more holistic strategy), careful monitoring is required to ensure the desired outcome and particularly to safeguard against inadvertent undesired outcomes (e.g., increase in corruption).

Penalties and punishments

Similar to many other forms of crime, the use of penalties and punishments has historically been a primary means of preventing corruption. Essentially, the risk of facing severe punishment is intended to deter individuals from engaging in corrupt acts. Penalties for engaging in corruption are often articulated in legislation. For example, in Canada, anti-corruption provisions exist in the Criminal Code (e.g., Sections 119 through 125) and in the Corruption of Foreign Public Officials Act. Additionally, non-criminal related sanctions can also be included in organizational policies and enforced via compliance statements or code of conduct violations.Footnote 11

A number of anti-corruption bodies have emphasized the importance of preventing corruption through the implementation of strict laws and penalties (OECD, 2017; Transparency International, 2022c). For example, Transparency International (2016) states that effective law enforcement and ensuring the corrupt do not avoid punishment is one of the “5 key ingredients” to preventing corruption. Additionally, the entire third chapter of the UNCAC focuses on the need for states to properly criminalize various acts of corruption (e.g., the bribery of national [Article 15] and foreign public officials [Article 16]; acts of embezzlement or misappropriation [Article 17]; and the laundering of proceeds of crime [Article 23]). Furthermore, numerous recommendations offered in the Charbonneau Inquiry suggest the creation of new and the strengthening of existing penal sanctions (e.g., recommendations 13, 21, 22, 33, 35, 36, 58, 59). In general, strong legal penalties targeting corrupt acts is one of the most commonly prescribed means of preventing corruption in both the public and private sectors.

While using penalties and punishments to prevent corruption is common, there is relatively limited empirical evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of this approach. Nevertheless, some research has demonstrated that increasing the harshness of penalties for corrupt behaviour can lead to a reduction in corruption. Namely, Fisman and Miguel (2007) in studying parking violations by UN foreign diplomats in Manhattan, found that when diplomatic immunity was taken away and parking enforcement measures were increased, unpaid parking violations among diplomats decreased substantially. Additionally, Bahnik and Vranka (2022), in analyzing bribe decision-making through an experimental study, found that participants accepted fewer bribes when the fines were larger and more probable.

Other research into the effectiveness of penalties in preventing corruption has noted that while punishments have the potential to be successful, there are a number of conditions necessary for success. For example, findings from a laboratory-based experimental study conducted by Abbink and colleagues (2002) indicated that the effectiveness of penalties could be dependent on the likelihood of detection. Namely, the researchers found that when participants actually believed that that their corrupt acts would likely be detected, increasing the harshness of penalties resulted in a significant reduction of corruption levels. However, the researchers also noted that participants generally tended to underestimate their likelihood of detection; therefore, in order for penalties to be truly effective in preventing corruption, one must ensure that individuals hold a high perceived probability of detection.

Beyond a high perceived probability of detection, the broader literature on the use of punishment as a behavioural modification tool (outside the context of corruption) has identified a number of other conditions typically required for punishment to be effective. Namely, research indicates that to produce meaningful behavioural change, punishments must be swift (i.e., in relatively close temporal proximity to the commission of the crime), proportional (i.e., severity of punishment is commensurate with the severity of the crime), and consistent (i.e., punishment is perceived to be a predictable and likely outcome of the crime) (Lukowiak & Bridges, 2010). These principles can be seen in the work of Banuri and Eckel (2015) who conducted a laboratory study examining the effect of short-term punishment on reducing corruption. The findings of their research showed that the institution of short-term punishments (i.e., crackdowns) is ineffective in preventing corruption as punishments are not consistently applied. During crackdown periods, there may, in some instances, be a reduction in corruption. However, following the crackdown period, corruption levels rebound to pre-crackdown levels (Banuri & Eckel, 2015).

Despite the common use of punishments as a method to prevent corruption, some research has argued against the approach. For example, Huther and Shah (2000) present the argument that countries such as China and Vietnam, which have serious consequences for people who engage in corruption (the authors reference that in some instances, the death penalty has been issued for acts of corruption), still have relatively high levels of corruption based on the CPI. The authors conclude that if harsh penalties were truly effective in preventing corruption, then we should see lower levels of corruption in these countries. Alternatively, one could argue that issuing the death penalty for an act of corruption violates the principle of proportionality, thus explaining the potential ineffectiveness of punishment in this context.

The use of penalties and punishments as a means of preventing corruption continues to be commonly used and widely advocated. In general, empirical research into the effectiveness of penalties and punishments for preventing corruption shows that a number of conditions are necessary for these methods to be effective – conditions that are not always met in practice. As such, the use of punishment as a means of preventing corruption should be applied with caution and potentially in combination with other prevention methods.

Risk management approaches

Risk management approaches to preventing corruption seek to proactively highlight possible areas of concern and develop appropriate measures aimed at mitigating or reducing the risks associated with such areas of concern. Approaches under this theme ultimately seek to prevent corruption by decreasing opportunity. Six different methods fall under this category: (1) audits and risk assessments; (2) due-diligence; (3) the four-eyes principle; (4) asset disclosure; (5) position rotation; and (6) merit-based recruitment.

Audits and risk assessments

Risk assessments include a process of identifying, assessing, and prioritizing corruption risks for the purposes of developing and implementing a plan aimed at targeting them. Risk assessments provide organizations with an overview of the vulnerabilities in their various processes and allow them to make informed decisions (Willems et al., 2016). Furthermore, they enable organizations to focus efforts on what are determined to be high-risk areas. The risks that organizations face can be both internal (e.g., insufficient reporting channels, conflicting incentives, lack of policies and procedures) and external (e.g., country, industry sector, type of operation).

A number of anti-corruption bodies have emphasized the importance of having proper auditing functions and risk-management frameworks (OECD, 2017; Transparency International, 2016). Namely, Transparency International (2022c) cites that risk assessments are the foundation of effective anti-corruption programs as they provide organizations with the necessary evidence-base to inform future decision-making. Additionally, the UNCAC in Article 12(2f) recommends that private enterprises develop sufficient internal auditing controls, as these are an essential step towards uncovering and preventing corruption.

There are a variety of different ways to conduct risk assessments and audits; however, in most instances, tactics are classified as being either top-down or bottom-up. Top-down monitoring involves members of a higher rank monitoring those beneath them on the institutional hierarchy (Serra, 2012).Footnote 12 Conversely, bottom-up monitoring (also known as community monitoring) involves community members or the potential recipients of the corruption benefits conducting their own monitoring of programs and/or higher up officials (Serra, 2012).

In their comprehensive review and analysis of the literature, Gans-Morse et al. (2018) found that there was a substantial amount of empirical research demonstrating top-down auditing as a relatively effective means of monitoring and detecting corruption; however, they also note that its effectiveness in preventing corruption over the long term is still to be determined. Olken (2007) conducted a randomized field experiment in Indonesia and found that introducing traditional top-down auditing procedures was much more effective in reducing corruption than bottom-up monitoring procedures. The researcher found that increasing the probability of a government audit from 4% to 100% led to a reduction in missing expenditures by about 8%, which after conducting a cost-benefit analysis, demonstrates that the benefits of top-down auditing greatly exceed their cost.

With regards to bottom-up monitoring as a means of preventing corruption, findings have been mixed (Gans-Morse et al., 2018). In their systematic review of 15 studies assessing the effectiveness of community monitoring interventions, Molina et al. (2016) found that such interventions can help to reduce corruption – especially when they promote direct contact between citizens and providers/politicians. However, research has been unable to determine the exact degree of effectiveness of these interventions.

Other studies have examined the effectiveness of combining top-down and bottom-up monitoring procedures, and have shown mixed results regarding their compatibility. Serra (2012) conducted an experimental laboratory study whereby she examined a public official's tendency to request bribes under two different scenarios. The first scenario involved a top-down auditing approach that resulted in a 4% detection rate. The second scenario involved a combined bottom-up monitoring and top-down auditing approach whereby citizens could report bribe demands, which would then activate a top-down audit with the same 4% detection rate. Despite the second scenario likely resulting in lower detection levels (it would only be equal if every client reported a bribe), the number of bribe demands was substantially lower. Therefore, Serra concluded that a combined top-down and bottom-up approach could be a more effective means of preventing corruption. In contrast, Gonzalez et al. (2020), in using the data collected by Olken's (2007) field experiment, found that implementing top-down audits can undermine rather than complement the effectiveness of bottom-up procedures. Essentially, the researchers found that when top-down monitoring is implemented, the involvement of community members decreases.

Outside of directly examining the effectiveness of the two approaches, a number of studies have also noted various caveats or conditions one should take into account when considering the use of auditing tools (Olken & Pande, 2012). For example, in their comprehensive review of the literature, Alfridi et al. (2020) posit that the efficacy of top-down audits is dependent on the type of punishment that could potentially result from the audit (in cases where corruption is uncovered). Namely, they found that audits resulting in legal punishment were more effective than audits that result in electoral punishment (i.e., not being re-elected or being removed from office). Furthermore, other studies have highlighted a number of institutional, political, contextual, and personal factors that are likely to impact the effectiveness of both top-down and bottom-up monitoring approaches (Buntaine & Daniels, 2020; Hollyer, 2012). For example, Buntaine and Daniels (2020), in their Ugandan field experiment, found that in order for the combination of top-down and bottom-up monitoring procedures to be effective, there needs to be a credible threat of escalation (i.e., impossible for officials to get away with ignoring claimants). Additionally, Hollyer (2012) argues that the effectiveness of bottom-up monitoring can be heavily impacted by the institutions that govern electoral behaviour (e.g., the presence or absence of electoral institutions, electoral rules in place, and demonstrated levels of clientelism). Furthermore, the effectiveness of top-down monitoring interventions can be mediated by the level of independence given to the oversight bodies in place (Hollyer, 2012).

In general, although difficult to draw any firm conclusions on the effectiveness of either top-down monitoring or bottom-up monitoring, there is some promising evidence in support of top-down monitoring procedures, while bottom-up procedures applied in isolation have yielded somewhat mixed results. Studies examining the effectiveness of combining the two approaches demonstrate that perhaps in certain contexts and under certain conditions (e.g., if there is a credible threat of escalation), combining top-down and bottom-up monitoring may be the optimal approach.

Due diligence

The risk assessment tactics examined in the above section focus mainly on the examination and prevention of risks that are internal to an organization. Due diligence, on the other hand, focuses primarily on investigating risks that are external to an organization. More specifically, this involves collecting, analyzing, and storing information on any third party the organization plans to work with (Transparency International, 2022c). Conducting organizational due diligence often involves verifying the reputation of potential business partners against different databases (e.g., databases containing sanctioned persons, blacklisted persons, politically exposed persons,Footnote 13 or persons with ties to organized crime) as well as various other investigative techniques.

Conducting due diligence when interacting with third parties is widely considered to be a good practice for organizations. In fact, the United Kingdom's Bribery Act even provides a defence for organizations found to be associated with corruption if they can prove they conducted proper due diligence (Bribery Act, 2010 s.7[2]). Multiple anti-corruption bodies contend that anytime there is the presence of a third party, there is a heightened risk of corruption (Transparency International, 2022c). The OECD, in their 2014 Foreign Bribery Report, highlights that 75% of all transnational bribery enforcement actions conducted between 1999 and 2014 involved payments through third party intermediaries. Furthermore, through an experimental study, Drugov et al. (2014) found that the presence of intermediaries significantly increases instances of corruption; the authors explain that intermediaries lower the moral and psychological costs of engaging in corruption, and thus, facilitate corruption.

Despite due diligence being a highly recommended best practice, there has been virtually no empirical research examining its effectiveness. While the risks posed by interacting with third parties has been established empirically, the effectiveness of due diligence in mitigating that risk has yet to be demonstrated. As such, future research is needed before any firm conclusions regarding this approach can be developed.

Four-eyes principle

The four-eyes principle is based on the premise that two individuals are less likely to engage in corruption than one. Therefore, this approach requires a second employee to verify and sign off on a colleague's decision. The logic behind this approach is that even if both employees are potentially corrupt, engaging in corruption may be less attractive due to a degree of uncertainty or the expectation of having to share bribes. However, certain scholars have critiqued this approach, arguing that it is motivated by distrust, diffuses responsibility, and could to lead to increases in corruption as corrupt employees may encourage each other (Abbink & Serra, 2012; Lambsdorff, 2015).

Despite the four-eyes principle being a common practice in the financial and lending industry, empirical research has largely shown this approach to be ineffective and in some instances, counter-productive (Wickberg, 2013). For example, in the context of an experimental study, Schikora (2010) found that when the four-eyes principle was introduced, the number of successful corrupt transactions increased. Frank et al. (2015) reported similar findings in their experimental study finding that group decisions, as compared to individual decisions, facilitate corruption.

There is some evidence to suggest that in contrast to a lack of impact (or counter-productive impact) of introducing the four-eyes principle on a single occasion (Bodenschatz & Irlenbusch, 2019), repeated use of the principle is more promising (Frank et al., 2015; Schikora, 2010). However, there is also evidence indicating that the presence of intermediaries (specifically, intermediaries who possess information regarding an official's threshold for accepting a bribe) has the ability to completely offset any positive effects yielded from the four-eyes principle (Fan et al. 2019).

In general, there does not appear to be any strong evidence in support of the four-eyes principle. Rather, the majority of the research examining this approach has demonstrated it to be relatively ineffective and potentially counter-productive.

Asset disclosure

Asset disclosure involves employees and/or officials providing a list of their assets, liabilities, income sources, business interests, potential conflicts, and any other information that could potentially leave them vulnerable or affect their decision-making ability. Transparency International (2014) highlights that asset declaration mechanisms are critical tools in the prevention, detection, investigation, and sanctioning of corruption. Namely, asset disclosure can help to identify persons who may be at an increased risk of corruption, it can aid in investigations and police detection by flagging significant changes in assets, and it can help quantify the costs of corruption (Rossi et al., 2012; Transparency International, 2014). The UNCAC in Article 8 (5) highlights the importance of asset declaration. Specifically, it outlines that each state signatory shall establish measures and systems that require public officials to make necessary declarations regarding their outside activities, employment, investments, assets, and substantial gifts. Furthermore, Article 52 (5) requires states to adopt appropriate sanctions for public officials who do not comply.

Empirical evidence surrounding the effectiveness of asset disclosure in preventing corruption is primarily positive, albeit limited. For example, Vargas and Schultz (2016) created their own index to measure financial disclosure regulations across various countries. The researchers used this index alongside corruption level indicators from the World Bank and found that the expansion of a financial disclosure system has a positive and significant effect on a country's control over corruption over time. Other studies have shown that the effectiveness of asset disclosure mechanisms is dependent on a variety of other factors (Djankov et al., 2010; Mukherjee et al., 2006). For example, Djankov et al. show evidence of a significant positive correlation between public disclosure and government quality, including lower corruption. However, this correlation only exists when two important criteria are met. Firstly, disclosures need to be comprehensive and include statements of all assets, liabilities, income sources, potential conflicts, business related activities, and gifts. Secondly, disclosure information needs to be made publicly accessible.

In sum, despite the fact that prominent anti-corruption organizations advocate for the use of asset-declarations in preventing corruption, there is relatively little recent empirical research examining the effectiveness of this approach. Although existing empirical evidence looks promising, it also demonstrates that a number of conditions could be necessary for success – namely, that asset disclosures should be comprehensive and made publicly available.

Position rotation

Position rotation involves periodically reforming organizational structures and processes – especially in environments that are already susceptible to corruption (e.g., procurement). The theoretical basis for this approach is that allowing public officials and users of their services to build trust and establish long-term relationships fosters an environment where corruption is more likely to take place (Bautista-Beauchesne, 2020). Therefore, position rotation prevents employees in high-risk sectors from developing long-term personal relationships with contractors and other third parties. While preventing such relationships from cementing may come with certain downsides (e.g., developing relationships with contractors and stakeholders could help to increase trust and facilitate smoother operations), this approach has received support from some anti-corruption organizations. For example, Wickberg (2013), in writing on behalf of Transparency International, recommends credit agents and those involved in the banking industry be subject to staff rotation systems and frequently change portfolios. Furthermore, the UNCAC in Article 7 (1b) proposes that those in public positions considered especially vulnerable to corruption should be rotated where appropriate.

The empirical literature examining the effectiveness of staff rotation in preventing corruption is limited to only a few studies; however, the findings are primarily positive. For example, in Bühren's (2020) experimental laboratory study involving German and Chinese officials, participants were found to have a reduced propensity towards corrupt behaviour following a staff rotation. Furthermore, Fišar et al. (2021) found that while rotating staff members did not reduce the number of bribes offered, it reduced the number of bribes accepted, as well as the number of inefficient decisions resulting from bribery (i.e., less manipulated decision-making). In addition, Abbink (2004) compared results from two different study groups – one in which the potential bribers and designated public officials were randomly re-matched in every round, and another in which the pairs remained fixed. The results of this study found that staff rotation significantly reduced the overall number of bribery transactions by nearly 50%.

In sum, empirical evidence in support of this approach is limited, but promising (this review was only able to find 3 meaningful empirical examinations). Further research into the effectiveness of this approach is still required.

Merit-based recruitment

Merit-based recruitment involves hiring professionals based on their qualifications (talent, skills, experience, competence) and ability to successfully complete the job rather than based on patronage or nepotism. It is believed that hiring professionals based on merit provides the necessary foundations to develop a culture of integrity, which ultimately helps to prevent corruption (OECD, 2020). Additionally, depending on one's preferred definition of corruption, the act of hiring based on patronage or nepotism could in itself be an act of corruption (UNODC, 2019).

The OECD (2020), in their public integrity handbook, recommend states adopt systems of merit-based recruitment and hiring to help mitigate the possibility of corruption. Additionally, Chene (2015), in writing on behalf of Transparency International, states that there is a broad consensus amongst governments that recruitment in the public sector should be based on merit and not patronage. Furthermore, the UNCAC in Article 7(1a) recommends that signatories take the necessary steps required to adopt merit-based systems for recruitment, hiring, retention, and promotion.

Empirical research examining the effectiveness of this approach, while somewhat limited, has been primarily positive, with several research teams employing large-scale survey methodologies identifying a significant relationship between meritocratic recruitment systems and lower levels of perceived corruption (Dahlström et al., 2012; Rauch & Evans, 2000). Moreover, Rauch and Evans demonstrated that meritocratic recruitment is more important for improving bureaucratic performance (and reducing corruption) than competitive salaries, internal promotion, or career stability. Furthermore, Charron et al. (2017), in their empirical analysis of survey results and public procurement data, found that the risk of corruption is significantly lower when employees' career development is based solely on merit as opposed to political connections.

Merit-based recruitment has typically been regarded as a “best-practice” and comes highly recommended by various anti-corruption bodies. Multiple empirical research studies have also been able to demonstrate the overall effectiveness of this approach. However, while this research has been generally positive, it has also been unable to pinpoint the specific mechanisms of meritocratic recruitment that contribute to its success (Meyer-Sahling et al., 2018). For instance, is it the fact that merit-based recruitment fosters a culture of integrity? Is it that candidates who have a high degree of merit are less corruptible? Is there some other explanation? Absence of this explanation notwithstanding, merit-based recruitment appears to offer an economically feasible option for preventing corruption (Sekkat, 2018).

Awareness and participation-based approaches

Creating awareness and allowing members of the public to participate in corruption prevention can not only help to highlight the importance of the issue, but it can also lead to the implementation of additional systematic checks and balances. Approaches under this theme seek to increase the likelihood of corruption being reported or detected, which, as demonstrated by Boly et al. (2019), can lead to lower levels of corruption. Five different methods fall under this category: (1) public awareness campaigns; (2) whistleblowing procedures; (3) freedom of information; (4) freedom of the press; and (5) E-government.

Public awareness campaign

One means of preventing corruption in both the private and public sectors has been through the creation of public awareness campaigns (also known as educational campaigns). Public awareness campaigns are essentially massive marketing efforts that seek to build public recognition of a specific issue. These campaigns can present information through a variety of fora such as billboards, videos, TV commercials, radio broadcasting, infographics, and many more. Support surrounding the use of public awareness campaigns is widespread in the anti-corruption community (OECD, 2017). Public awareness campaigns come in different sizes and can last from days to years. An example of a public awareness campaign targeted at corruption is the UNODC's International Anti-Corruption Day event (UNODC, 2021): This is an annual event targeted at raising awareness and garnering public support for the UNODC's fight against corruption. Every year, the campaign has a specific theme and slogan that helps to target a specific aspect of corruption. In 2021, the campaign lasted a total of six weeks and raised awareness surrounding the interaction of corruption and (1) education and youth; (2) sport; (3) gender; (4) the private sector; (5) COVID-19; and (6) international cooperation. The UNCAC has also included a number provisions recommending states take certain measures to increase public awareness of corruption.Footnote 14

Empirical research specifically examining the effectiveness of public awareness campaigns in preventing corruption is extremely limited (Gans-Morse et al., 2018). Some research, while not directly examining public awareness campaigns, has provided indications that increasing awareness surrounding corruption may produce positive outcomes. Köbis et al. (2019) conducted a laboratory field study in a South African town and found that placing posters containing anti-corruption and anti-bribery messages resulted in participants engaging in fewer bribery scenarios. Furthermore, as found by Abbink et al. (2002), people tend to underestimate the likelihood that their corruption will be detected. Therefore, Abbink and Serra (2012) highlight that public awareness campaigns could help to address this frequent underestimation, thereby creating less inclination for actors to engage in long-term corruption.

Other research has found that public awareness campaigns may be ineffective or even counter-productive. For example, Denisova-Schmidt et al. (2015) carried out a micro-level experimental survey involving a group of 600 Ukrainian university students. From this study, the researchers found that educating students on corruption led to certain increases in student tolerance, as it demonstrated the extent to which other members of society engage in such acts. Furthermore, Banerjee et al. (2021) found that the use of public awareness campaigns may be especially ineffective in countries where corruption is extremely prevalent as it would not create a heightened degree of concern. Namely, the researchers found that in countries where corruption is widespread (they use Kenya as the example for their study), actors simply perceive corruption as a “cost of doing business” and they are no more dissuaded by it than they are by other “legitimate” business costs.

A smaller portion of the research literature has also examined various conditions and contextual elements that can influence the effectiveness of public awareness campaigns. For example, Denisova-Schmidt et al. (2019), from their online experiment involving 3000 Ukrainian students, demonstrated the importance of presentation methods when communicating anti-corruption messaging. Namely, the researchers found that presenting students with a catchy, thrilling video about corruption was more effective in promoting awareness of the negative consequences than TV news or documentary-style videos. Additionally, Denisova-Schmidt et al. (2021), in their analysis of Russian university student attitudes towards corruption and academic integrity, found that different sub-groups tend to react differently to corruption education campaigns, with these campaigns creating negative perceptions amongst some and more tolerant views amongst others. Namely, the researchers found that educational campaigns cultivated stronger negative attitudes towards corruption amongst those who frequently engage in corrupt acts (as measured by tendency to engage in academic plagiarism) and induced more tolerant views of corruption amongst those who engage in corrupt acts (i.e., academic plagiarism) less frequently. This research demonstrates the need for caution to be exercised when creating educational or awareness campaigns given the possibility that such campaigns could have undesired heterogenous effects on different groups.

Despite public awareness campaigns being a widely used and recommended technique, there is insufficient evidence on the effectiveness of this approach in preventing corruption. Relevant research is mixed, with some demonstrating successful outcomes and others highlighting specific instances where the approach may be ineffective or counter-productive (i.e., in settings where corruption is already extremely prevalent or in the event that educating individuals on the prevalence of corruption leads to increases in tolerance towards corruption).

Whistleblowing procedures

Whistleblowing involves an employee or member of an organization passing on information regarding a wrongdoing. Typically, such wrongdoing is of an illegal or immoral nature, such as financial misconduct, discrimination, fraud, abuse, or corruption. Therefore, establishing strong whistleblowing procedures involves providing employees with a quick and effective means of reporting such wrongdoing should they come across it. Theoretically, this is believed to lower corruption as it removes some of the common barriers that can prevent potential whistleblowers from reporting.

The importance of whistleblowing procedures and establishing proper protections for whistleblowers has been highlighted by a number of prominent anti-corruption bodies. In general, there is a common consensus that establishing effective complaint mechanisms and ensuring that those who do report corruption are protected, are essential elements of any integrity management system (Chene, 2015; OECD, 2017; Transparency International, 2022c). In addition, the UNCAC in Article 33 highlights the need for states to protect whistleblowers who report in good faith. Similarly, the Charbonneau Inquiry, in its eighth recommendation, calls for better support and protection for whistleblowers. An emphasis on the importance of whistleblowing has also been seen in the province of Ontario; in July 2016, the Ontario Securities Commission introduced a variety of pro-whistleblowing measures including anonymous reporting, the possibility of compensation, the establishment of a designated whistleblowing office, and the addition of anti-reprisal provisions to the Securities Act (Jain, 2017).

Despite the widespread support for establishing strong whistleblowing procedures, the effectiveness of such policies in reducing corruption remains greatly understudied (Gans-Morse et al., 2018). Some research has examined factors that could impact the success of whistleblowing procedures. Schickora (2011) found that the effectiveness of whistleblowing rules is dependent on how they are structured. In an experimental study, Schickora found that only whistleblowing under asymmetric leniency for the bribee reduces the occurrence of corruption. In other words, the only successful whistleblowing scenario is when the official (bribee) is given the opportunity to “blow the whistle” without risk of penalty. Furthermore, Suh and Shim (2020), in their study of the South Korean financial sector, found that in order for whistleblowing policies to be perceived as effective, it is first necessary to establish an organizational environment that fosters ethical behaviour. Namely, whistleblowers are more likely to come forward if their organization is supportive of such actions and they do not face the potential for serious backlash.

While the effectiveness of whistleblowing procedures in preventing corruption has been greatly understudied, this method appears to have a strong theoretical grounding and has received support from some of the most prominent anti-corruption bodies in the world (Chene, 2015; OECD, 2017; Transparency International, 2022c). In general, proponents and supporters of this method could benefit from further research as a strong evidence base is currently lacking.

Increasing transparency

In the context of corruption, transparency can be defined as “the release of information about institutions that is relevant for evaluating those institutions” (Lindstedt & Naurin, 2010, p. 301). Increasing the transparency of an organization can help to reduce corruption and build trust as citizens are able to hold government officials more accountable and enforce greater electoral responsibility. Many risk-management approaches mentioned above tend to rely heavily on organizations monitoring and assessing themselves, which can be problematic in wholly or majorly corrupt organizations. As such, a key principle of transparency is encouraging the participation of outsiders and external parties. Empirically, research into the effectiveness of increasing transparency has focused on three specific approaches. Namely, these include: (1) introducing freedom of information laws; (2) allowing for a freedom of the press; and (3) the adoption of E-government.

Freedom of information

Freedom of information (FOI) laws allow citizens and other interested parties to access government documents and records without having to show a legal interest. An example of such laws includes Canada's Access to Information Act whereby Canadian citizens, permanent residents, and corporations can request access to documents and records that are under the control of federal institutions. The importance of adopting such laws is also mentioned in the UNCAC – namely, in Article 10(a) and Article 13(1b), where it is recommended that the general public be given effective access to government information and decision-making processes.

In general, there has been some debate regarding the empirical effectiveness of FOI laws in preventing corruption, as some researchers found that the adoption of such laws was associated with higher levels of corruption (Costa, 2013; Escaleras et al., 2010). However, Gans-Morse et al. (2018), in their review of the literature, caution that such findings may be a result of researchers relying on the CPI and other perception-based indicators as a measure of corruption. Essentially, if FOI laws lead to increased exposure of corruption, then the perceived levels of corruption may increase despite there being a decrease in actual corruption levels. The findings of Cordis and Warren (2014) support this conclusion, finding that following the adoption of FOI laws, corruption conviction rates increased significantly; however, over time, the rates fell as actual levels of corruption were decreasing. The findings of Vadlamannati and Cooray (2017) also support this conclusion as their study, which used panel data from 132 countries, demonstrated that the adoption of FOI laws was associated with an increase in perceived corruption in the short term; however, perceived corruption levels gradually declined with the elapsing of time since the FOI law adoption. Therefore, the apparent increase in corruption levels following the institution of FOI laws may actually be an artefact of increased detection rates. The net effect of FOI laws tends to be a decrease in actual levels of corruption.

Other research has demonstrated that the simple adoption of FOI laws is likely not sufficient in reducing corruption on its own. For example, Lindstedt and Naurin (2010), in analyzing data from various World Bank indices, found that simply making information available to citizens will not help to prevent corruption if conditions for publicity and accountability are still weak. In other words, increases in transparency must be accompanied by various other reforms, such as media freedom, criminal sanctions, and education (i.e., providing people with the ability and capacity to understand the information given to them). Furthermore, a study carried out in India by Peisakhin and Pinto (2010) showed that when requesting information from the government, those who submitted bribes received their requested information much faster than those who just requested information under the Right to Information Act. The latter demonstrates that even if FOI laws are implemented, there still may be opportunities for corruption (e.g., to avoid significant delays).

In sum, FOI laws appear to possess some effectiveness in their ability to prevent corruption. However, as other research has demonstrated, this method is not without its flaws and likely lacks the capability to completely prevent corruption on its own.

Freedom of the press

Allowing for freedom of the press involves allowing news and other media agencies to investigate and report their findings without being repressed or controlled by government. It is believed that allowing for press freedom will help to prevent corruption as it increases the likelihood that corrupt acts will be uncovered and published.

Various empirical studies have demonstrated a link between press freedom and corruption levels (Brunetti & Weder, 2003; Camaj 2012; Chowdry, 2004; Hamada et al., 2019; Starke et al., 2016). Specifically, research shows that countries with higher levels of press freedom are characterized by lower levels of corruption on various corruption indices. Therefore, one could reasonably conclude that increasing transparency in the media and allowing for freedom of the press could be an effective measure in preventing corruption. However, it should be noted that many of these findings have only been able to demonstrate a strong association between press freedom and corruption levels – not a causal relationship.

In general, there is favourable evidence supporting the effectiveness of a free press in preventing corruption, and there does not appear to be any evidence to suggest a counter-productive effect.

E-government