Choices and Consequences - Offenders as a Resource For Crime Prevention

Table of contents

Introduction

In a world where very little seems fair, there is a sizeable collection of people who spend most of their daily lives fighting to even the odds. These people are seldom well paid and they are frequently overworked.

Across Canada, people from many First Nations and Inuit communities work on the front lines. They work with offenders (both youth and adult) and young people who, they hope, will not become offenders.

In February of 2002 some of these people came together on the lands of the Goodstoney First Nation in Alberta. They gathered to talk about what people, especially offenders, might do so that there would be fewer Aboriginal offenders in the future. As a part of their own healing journey offenders must take responsibility for their offences. Part of taking responsibility is seeing the criminal acts as the abuse of trust that they are. By working with young people offenders can strengthen the community that they have harmed in the past by these acts.

The Aboriginal Corrections Policy Unit of the Solicitor General of Canada convened The Gathering. The sponsors hoped to have an ongoing discussion of this topic with community members and also sought the basis for a future how-to manual for people who want to work in the area of crime prevention and offender reintegration.

What follows is a collection of thoughts on the topic of how Aboriginal offenders may offer their talents to keep young people from coming into conflict with the justice system. It includes background work that has been done in this area as well as descriptions of some fine programs that no longer exist and one that continues. The words of the people who attended this gathering are also included - they are thoughtful words spoken with great power and emotion. Above all they are words spoken from the heart.

The people who attended The Gathering have generously agreed to share their thoughts and ideas in the hope that Aboriginal people across Canada will take from the words whatever they find useful. It is also their hope that this will, in some small way, make life better for the next seven generations.

The Aboriginal Corrections Policy Unit hopes that this report will help the conversation that began at The Gathering to continue, particularly among those individuals and communities that were unable to attend The Gathering.

The Precedents or Up 'til Now

A good place to start any discussion of this topic is with the "Scared Straight" program that began in Rahway (NJ) Prison in the mid-1970s. As a result of this programs perceived local success, a documentary was made. The documentary was narrated by actor Peter Falk and received an Academy Award in 1979. Nevertheless, as early as 1980 people were asking questions about the effectiveness of Scared Straight. In that year a team of researchers from Rutgers University did the first controlled test and discovered that there was no significant change in attitude between the young people who had been part of the Scared Straight program and those who had not. They further concluded that crime prevention was more influenced by certainty of punishment than by severity. As the Rutgers study continued the researchers found that, in fact, the young people in the control group did better when subsequent offences were considered than the group in the program.

Despite the lack of evaluative support the "Scared Straight" program was copied outside the United States in places as diverse as Canada (Millhaven Institution in Ontario), Britain, Denmark and Norway. In a meta-analysis, that is a study that combines the results of many different studies of the same issue, James O. Finckenauer and Patricia W. Gavin concluded that, "Scared Straight programs have little success in deterring crimes". In fact "In those cases where positive findings have been reported . there are a host of problems with the reliability of the information." (Finckenauer & Gavin, p.136) Many of the studies "stacked the deck" with young people who were no real risk to begin with. Nevertheless, Scared Straight programs continue because of contextual factors such as political climate, media climate and simple inertia. These contextual factors are backed up by the all-too-common belief in the panacea of deterrence. Together they have kept Scared Straight programs going for many years past usefulness.

Beyond Scared Straight programs the whole restorative justice movement might be considered. While not directly on the topic, we acknowledge that many of the restorative justice models, by including whole families, include both offenders and young people who are listening to them talk about the mistakes that they have made. Of these restorative justice approaches, the two that are closest to this topic are the Navajo Peacekeeping model in the southwestern United States and the Maori Family Group Conferencing model in New Zealand.

When Navajo people do harm to themselves or others their people "say that the person 'acts as if he has no relatives'," an expression of imbalance. For the Navajo, peacemaking restores the person's self to the world. Because Navajo culture is so keenly attuned to the clan system the peacemakers' process of 'talking things out' includes members of both the victim's and the offender's extended families. As such the young people would hear everyone involved "telling their stories' as well as the peacemaker's advice on how to regain balance (the principal aim of the process).

As with the Navajo, the Maori Family Group Conferencing model assumes that family and community are central to healing the imbalance of crime. The Moari assume that "children grow up best when they themselves participate in decisions that affect their lives". (ibid, p.61) Although many family group conferences deal with young offenders there are certainly other youth there to watch the proceedings and learn from the mistakes of others. This model supports the concept that a restorative approach is more successful than a punitive one. "Perhaps the single most important feature of the conference format is the inclusion of all present in the decision-making processes for making things right." (ibid, p.63)

The value of retribution predominates on the political landscape of criminal justice policy. To counter this ideology restorative justice aims to meet the needs of everyone in a community, including those who did the harm. Thus, programs based on need rather than revenge, programs that focus on healing rather than punishment, programs that publicly speak to the harm caused and the victims' pain - such programs address the needs of a community rather than an individual. In doing so, they more closely match the traditional values and practices of First Nations that are searching for an alternative to the many failures of the mainstream justice system.

In Canada there are three projects, of which we know, that have used Aboriginal offenders to work with Aboriginal young people to keep them on the road that leads away from the criminal justice system.

The Stone Path

The Stone Path was a community-based intervention program for First Nations youth in the province of Manitoba. Its co-ordinator, Susan Swan, is with the Winnipeg police but the project was not run from an institution. The aim of the Stone Path was to acquaint Aboriginal youth, ages 10 to 14, with the dangers of gang involvement. It was hoped that this sort of education would equip the young people with realistic ways of resisting recruitment and the lure of urban gangs.

The Stone Path used former gang members telling their own stories to young people in their home communities, wherever those might be. Before the project started it was agreed that the ex-gang members would not say to which gang they had belonged. In this way, the gangs could not be glorified to the impressionable young people who were hearing the stories.

The young people at these sessions learned about the realities of gang recruitment, what happens in gangs, and how difficult it is to leave a gang. The information was delivered in one-day workshops. The co-ordinator and the former gang members travelled across the province, to all First Nations, to make their presentations.

It was important to reach young people in their home communities because many of them would come to urban centres for their secondary schooling and, there, be vulnerable to gang-related pressure with which they would have no experience back home. Equipped with preventative techniques on how to avoid invitations to join gangs, the Stone Path tried to steer young people toward a more balanced way of living while giving them coping skills to face the day-to-day pressures outside the classroom.

As Susan Swan noted: "It was important to work with youth before they got into the system. There was nowhere for the police to send someone if they needed help before they actually got into trouble."

Such action provides a much more viable long-term strategy in that by drying up the sources of recruitment it gets to the criminals before they become criminals. The program offered a double benefit in that it underlined for the ex-gang members just how negative being a gang member was as well as replacing being a gang member with the more positive role of being a mentor on the right road.

Stone Path selected youth that were not current gang members. These young people participated in sessions on gang theory, the realities and consequences of gang membership, the dangers of substance abuse, and discussions about values. The program tried to involve youth in after-school social activities of their own choosing and hence minimise the opportunity for gang involvement. Such activities included sports, travel, recreation, and job skills workshops.

The Stone Path was put together primarily from gut instinct and the tenacity of its co-ordinator. There has been little research preceding it and no follow-up since it ended.

Partners in Healing

Partners in Healing was based in British Columbia. The idea came from a medicine wheel group where people noticed how well offenders got along with young people. This observation initiated a search for a program that would link the two to their mutual benefit. Research showed that Scared Straight not only was ineffective, it would have been inappropriate for First Nations cultures. After the program was first set up it took a long time to get the programme up and running because of the logistics of pulling a team together.

It was overseen by a project co-ordinator and a steering committee composed of Elders, institutional parole officers, correctional staff, community members, and a lawyer. While visiting prisons the project co-ordinator and an Elder conducted interviews and circles. Then they chose three inmates who had a minimum classification. In the selection process preference was given to lifers who were knowledgeable in the area of native spirituality. Once this was done, all the school districts, colleges, and universities in the area were approached with a request to talk to their Native Education classes. It took almost a year before the first circle took place.

Elders and school counsellors supervised all the work. The two met beforehand to discuss what the offenders and youth might talk about. The idea was to give youth a factual look at life inside prison without the glory or glamour; to let them see what it is like to lose your freedom. The kids became engaged and would ask a lot of questions. Counselling was available with the Elder as issues arose on the spot. The Elder was also available for follow-up counselling if that was required.

Usually the classes came to the healing lodge in the Mission institution for circles. (This minimised security issues at the schools.) In the circles young people were introduced to traditional teachings. Some of the young people included in the Partners in Healing program came from youth detention centres. When some of the brothers from the inside spoke, it moved youth that had not talked about the issues before. Such frank discussions led to a positive dynamic and relationships were formed. Some young people went from making drums in one of the workshops to forming a drumming group.

There was a debriefing after each circle so that the participants could find balance, and so that both the young people and the inmates could grow. With careful selection (i.e. not choosing someone who would glorify prison life) the program had a great deal of positive comments. Feedback from the young people confirmed that offenders were doing what they had set out to do. The offenders, themselves, got a great lift out of it. This process helped to transform the adults involved into healthy individuals who were able to give something back.

As one participant said: "It helped them find their gift."

Unfortunately, Partners in Healing ended in 1999 for lack of fiscal and administrative support. Nevertheless all the brothers who participated are still on the outside and there continues to be a youth drum group.

Broken Wing

At Saskatchewan Penitentiary the Broken Wing Program was implemented in 1995. At that time people felt that kids who were taking tours of institutions were getting the wrong impression. They saw new equipment in the gyms, televisions, regular meals, and what looked, to them like a pretty good time.

In the Broken Wing program a team of two Aboriginal offenders and two CSC staff members make presentations about the life-long effects of conflict with the criminal justice system. Elders and staff in the institution carefully choose the participating offenders. Often they are recruited from Alcoholics Anonymous because those men have already taken steps in their recovery and are used to talking about themselves and their history. To begin they work on a personal healing plan, part of which is to go out and talk to people.

Although Broken Wing is frank in its discussions it does not emphasise scaring the participants. Someone who works in the program said: "We don't try to scare kids, but we don't sugar-coat it either."

It is hoped that in their participation offenders will advance their own healing journey by returning to the community to make apology for their anti-social behaviour. The team, which speaks to groups from grade one to the end of secondary school and their parents, gears its presentation to its audience. Though no formal evaluation of Broken Wing has been done its positive effect is evidenced by the numerous requests for additional presentations.

The Gathering

The core of ideas in this report comes from the 22 people who gathered on the Goodstoney lands in February of 2002. The participants were a mix of government and Aboriginal community representatives from both urban and rural areas. What follows are the ideas and dreams that they shared during that time. Throughout those four days certain themes arose and were repeated with different variations. Within this discussion of the themes are the words of the people who shared their ideas at The Gathering.

How to reach young people:

The saying that "it takes a village to raise a child" applies to the advice given by people at The Gathering. Frequently, people said that there should be a team because it takes a whole community - outreach workers, police with common goals, parole officers, child and family service workers, friendship centres - to work with and support the young person. As one participant from the Hollow Water First Nation said: "We don't have a facility, just a community. People get sentenced to my community and all that we can offer them is a home."

The advice was clear: Go wherever young people are - schools, conferences, or court - to talk to them and offer help. And go early. Get there before something happens to place the youth in conflict with the criminal justice system. Work not simply with the young people, but also with their parents and families.

"We work with youth. A lot are from different gangs. When they come together they set aside animosities at ceremonies. When the offenders and the youth got together it was like the men were not from prison and the youth were not from the school, but like we were a family. But it was hard because the parents didn't like it and I had to explain to them that this was one of the ways people learned in our culture."

Ask youth what they need and then try to incorporate those ideas into the treatment plan (in other words - ask them for their thoughts and then listen to what they have to say). Such acknowledgement of feedback is important because not all projects are solid - an example was given of a project that just made young people angry so instead of helping, it made things worse. All young people should be treated as human beings. It is this basic sign of respect that most of them are looking for.

At the same time it is important to recognise that there are some issues that are faced by young people, for example sexual abuse, that may be better shared in a circle of only young men or young women and facilitated by someone of the same sex.

Using offenders as resources:

People at The Gathering thought that the use of former residents as facilitators would be effective because their first-hand experience lends credibility to the message.

One young person at The Gathering said: "It is better for someone who has lived the life I live to help me. Part of healing is sharing with other people who have the same experiences."

Acceptance of responsibility should be a prerequisite for any offender involved in a program such as the ones being proposed. Some participants noted:

"Women inside the healing lodge need so much work when they arrive that they cannot help anyone else until they do that work."

"Before offenders can be utilised much education has to happen for them within the institutions."

"The only ones who can help others are the ones who have helped themselves."

There is a risk involved in relationships that form between older individuals and younger, impressionable ones - it is important to be alert to such a risk. Offenders who have been following a healing path know how critical it is not to glorify prison and a life of crime. Not only is it important to have offenders talk about the negative side of choosing the wrong path, they should also talk about the things that could have helped them along the way.

Some thought that among any group of Aboriginal offenders that are on a healing path they, themselves, know who are ready to leave and be out on their own.

"They need to be living their culture and be sincere."

"For people getting out . when they are ready they are proud of their heritage and they know how to fit into the world ... [that is why] . it is important that native-specific reports [on offenders] are given as much weight as regular ones."

Aftercare - follow-up and follow-through:

Whether healing circles and discussions take place inside the institution or out, it is important to have counselling available at all hours of the day and night. Reactions do not happen immediately. Sometimes there is a delay. Without that support all the positive things that can come out of discussions in the circle may be lost. Even worse, a person who has disclosed something terrible like sexual abuse may become suicidal without the kind of back-up that will help talk it through.

It is important to have someone there for support because if there isn't someone there, people, whether offenders or youth, will return to what they know - and that will probably be the thing that got them in trouble in the first place. With regard to offenders, some people said:

"It is important to remember that the institutions create the kind of safe environment that many brothers have never known before. The institution becomes a safe place and other inmates become their family. If there are no places for them to feel safe in communities then the brothers and sisters return to the institution where they feel safe and understood. Most of the time they will only go 'unlawfully at large' as an avenue to return inside without hurting anyone."

"It's not really the drugs or alcohol that's the problem, it's the living part - that's why people need aftercare."

Traditions and Protocol:

As a part of working with young people, as with all human beings, it is important to remember that the core of a solid relationship is respect. With that as a basis people can begin to speak to each other with fewer barriers to positive action.

It is important to understand that not all Aboriginal people are alike in either their customs or their approaches. Some Aboriginal people display few of the traditional cultural behaviours of their nation because they did not grow up with such behaviours as part of their environment. In addition, across Canada, the different peoples have differing cultures and so what is central in one culture may be peripheral or non-existent in another. The important thing to remember here is that Aboriginal people throughout Canada respect the traditions of other cultures. One thing on which most Aboriginal people agree is that a holistic approach is best. The idea that health is not just physical but also mental, emotional, and spiritual is central to all healing

It is important to respect the protocol of the particular people with which you are working. At a minimum there should be a thank-you for the use of traditional lands and a gift for those of whom you are asking something.

Elders and Mentors:

"Before contact with Europeans, all First Nations cultures in North America included Elders. They were men and women who performed one or several roles depending on their training and knowledge. Few Elders were capable of doing everything that Elders did but they were all teachers. As the repositories of tribal history and knowledge, Elders, as teachers, occupied an important role in the stability and evolution of their cultures and their communities. The gradual marginalization of tribal institutions by the evolution of the state and international economies throughout the Americas left Elders with few roles to occupy in the 20th century. By the 1970's, Elders re-emerged in many First Nations communities. Dissatisfaction with the effects of modernization in families and communities led people, young and old, to revisit the sources of traditional wisdom, the Elders. To many outsiders, Elders have achieved a kind of mythic status in today's society. It would be wrong to assume that every person who self-identifies as an Elder or is recognised as such, is capable of conducting traditional First Nations ceremonies or ministering to the spiritually bereft." (Strengthening Relationships, McCue, pp18-19)

Throughout The Gathering people spoke of the need to have someone who can relate to young people and their experiences with compassion. This is where an Elder or a mentor can play a role.

"Sometimes it takes an Elder to convince a guy that helping out young people is a good next step."

"It is interesting how the support of an Elder can cause offenders to want to become more involved."

With a history of working with troubled people, often Elders know who is ready, either offender or youth, to take a step in their personal healing and in working with others.

"Elders know because we trust them and we open up to them."

Inside institutions Elders can assess people by their level of participation and interest. Elders can help with a healing plan and assess progress as the person works through the steps. Effective use of Elders and mentors leads to an ever-healthier community.

"Elders try to create an environment where there is a place for [the brother] so that he can be involved because he wants to be rather than because he has to be. [The Elder] works with whatever talent links the individual to the community."

Not everyone has the same gifts, for example, not all want to or believe that they can speak in public. This is consistent with most Aboriginal cultures where people were acknowledged for their expertise in particular areas - no one was expected to be everything to all people. Nevertheless, some people who are modest or shy may need to be encouraged or even to be taught to be mentors.

"Mentoring of all different kinds is important. Whether someone is inside or out, they can be someone with something to share."

Sometimes mentoring simply means supporting people by spending time with them. Mentoring can happen in a program of peer counselling if those who are counselling are, themselves, healthy. It is crucial to remember that those who can help others are those who have made positive changes in their own lives.

"Mentors must be role models themselves. We call them 'popcorn people', the ones whose behaviour says everything. Elders must build respect among the people that they are trying to help."

"How do you determine who is a bona fide Elder? Be real; be honest."

"There are a lot of sick Elders who laugh at our process - that's because they're sick."

"When I was living a negative lifestyle I looked up to negative people, now I look for a sounding board with compassion."

Funding:

Although it was not a central topic for discussion the question of how to fiscally support these healing programs came up from time to time in the discussions. What the participants thought about the topic is best said in their own words:

"Programs begin with funding and when the funding stops, so does the program, whether it was a good program or not. [So] it's important to have a plan for what happens when the money runs out. You have to use resources (people) that are available without it being a program. We have no funding for men's healing circles, community socials, or sweat lodge ceremonies but we do them."

"We have to get away from the mindset of pilot projects and get concrete commitments from government who have a fiduciary responsibility. It's better to have a national program rather than little bits and pieces across the country."

"You cannot tell people how to heal - it is when they are ready inside. Listen to them and they will tell you what they need and when . [Governments say] 'I'm going to fund you for two years so you better heal everybody in two years.' . It doesn't work that way."

Project Ideals:

Toward the end of The Gathering the participants discussed the components that they thought would be important for a good youth-offender mentoring program. It was readily acknowledged that not all programs had to be the same to be successful. Certainly, due to different dynamics, resources, geographical locations, and cultural backgrounds successful programs might look very different. Nevertheless, there was a core of components that all successful projects would have in common especially healthy Elders who understand their traditions. Long-term results with young people will only come with patience. Stable funding means that energy can be spent on healing rather than writing proposals.

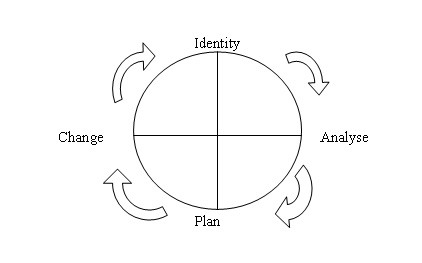

Together some of the participants drew a diagram to show the importance of working toward a common goal of harmony and balance instead of fragmenting and compartmentalizing.

Image Description

The diagram above is of a medicine wheel (a circle that is quartered from top to bottom and left to right) with arrows on the outside moving clockwise around the medicine wheel between the words. At the top of the medicine wheel it has identify, then analyse at the right, plan at the bottom, and change at the left. The medicine wheel was used to show how the underlying premise of "do no harm" could be achieved by moving from identifying an issue, analysing it, planning for change and then moving toward change.

Using the medicine wheel and the circle would bring out individual talents. Too often, they said, we try to take a shortcut from analysing to change without taking the time to plan. This may take a little longer but it is more durable in the long run. It must be based on the first premise of 'do no harm'.

Mainstream programs and initiatives identify an issue, analyse it, and then move to change directly without planning. This approach is a triangle and does not contain the necessary components to make it work. As a result, these programs often do not work for Aboriginal people and many do not stand the test of time.

Inside institutions there must be Aboriginal programs so that offenders will have support to work on their own issues. All staff in institutions should have cultural awareness training and regular refresher courses. As happens in most Aboriginal cultures older offenders could be encouraged to work with younger ones in a healthy way.

After offenders leave institutions there should be a continuum of care and a continuation of the circle. Encouraging people and organisations to go inside the walls to meet offenders would enhance this. Healthy brothers and sisters could speak in schools and friendship centres and feel useful by sharing their thoughts.

One participant said: "We need to stop keeping people in jail who are willing to take responsibility for their actions in their own community. We need to treat people with respect and that will be returned. Some people who have been through our program meet as a young men's group. Nobody pays them; they do it on their own. We have a grandma who gets together with the young moms. We recycle people so those who have been through the process get to a point where they are ready to work with those who are just coming into the program."

When programs are working well the parts feed off each other and all are better.

The Youth: What Do They Say?

Native Counselling Services of Alberta sponsored a research project to consider the reasons why youth do not re-offend. In Getting Out and Staying Out: A Conceptual Framework for the Successful Re-integration of Aboriginal Male Young Offenders they endeavoured to identify what was key to the development and maintenance of successful behaviour and lifestyle in young offenders.

The semi-structured interviews of the study pointed to a dichotomy in the minds of the young men in the study. Negative consequences (primarily, incarceration) were perceived in one of two ways: either it was manageable or it led to a turning point that resulted in a major change in lifestyle. At the time of their earliest conflicts with the criminal justice system peer group influence (usually negative) was most important to them. Maintenance of a relationship with that group was more important to them than the consequence of going to jail - something that they saw as manageable.

As the youth got older their relationships broadened to include people who were not part of the negative peer group. Positive relationships with these people, often a girlfriend or a child, frequently led to a turning point. That resulted in a need to reflect. Such reflection forced the young man to look at his life and see the need for change. Often this sober consideration of life led to a crossroads and the attitude that "enough is enough". Then the individual came to accept that he was tired of everything associated with crime and was feeling remorse for his actions.

After those initial revelations the young person began to see linkages between substance abuse and the risk of being incarcerated, even if they were still using alcohol or drugs. Often the consequent, and positive, desire to "grow up" reflected the person's desire to be seen as a responsible adult by those around him. The final step in this process, and often in successful integration, was the desire to take on responsibility and be accountable for his own actions.

The steps to successful reintegration do not happen quickly. Like any behaviour modification it involves time and the movement may waver back and forth rather than heading steadily forward. How an individual acts depends on how he views the consequences and that view, whether positive or negative, is based on what is important in his life. Thus, he is constantly analysing the choices that he has to make. The priorities in his life guide his decisions, something that is true for most of us. It is at this point that we look to see how former inmates, who have made many negative choices, can assist in keeping young people from following the same path.

In March 2002 a representative of the Aboriginal Corrections Policy Unit of Solicitor General Canada talked with a group of youth in Young Eagles Lodge in Vancouver. The Lodge aims to steer young people in a positive direction so that they move toward a healthier way of life.

When they spoke, many of the young people confirmed both what people in the Native Counselling Services of Alberta research said and what many of the participants at The Gathering had discussed. One of the youth said that he would never 'rat' on one of his brothers (peers). He said that he would rather do a year in jail for something he didn't do rather than rat on his peer. When it was suggested that if he really was your friend then he wouldn't expect you to take the fall for him, the young man said that only another criminal would understand. So we can see how important peer groups are to these young people and how, if we hope to show them the right path, we must work with the people who are important to them as well.

Another theme that was echoed by the youth at Young Eagles was the importance of working with people who understood their problems.

"Sometimes you meet people and your life is exactly like theirs . they understand." "Some staff [at youth facilities], they went straight to school and then they come [to the facility] - they don't know."

Although they could not always articulate exactly what was needed the youth at Young Eagles understood, as deeply as did the frontline workers at The Gathering, that aftercare was vital to keeping people out of institutions and away from the criminal justice system.

"I know some kids who've been in jail. They don't know what to do when they get out. They just want to go back in."

What these young people understand is that if you are raised in an unhealthy environment it takes about as long to get healthy again as it took to get sick in the first place. The people who also understand that, on a visceral level, better than anyone, are offenders.

The Offenders: What Do They Say?

In addition to the conversation with the youth at Young Eagles, a discussion took place with two men from the Circle of Eagles halfway house. One of these men had worked with the Partners in Healing project; the other man had been recently released on day parole. As the young people had done, they reinforced many of the ideas that were shared at The Gathering.

"In order for this to work you need to have your heart in it. You need to be sincere in wanting help . for example, a guy may not have been around for his own kids but may be able and may want to give something back."

Although these men thought that the offender-helping-youth idea was a good one they saw that it could be misused if it was not carefully supervised.

"If you use guys inside a minimum security facility you have to ask yourself why is the guy involved? Are they trying to buy their way out by making it look good on paper? Are they jumping the hoops just to get out?" "What happens if kids become dependent on these people and then they get out and turn their back on them? This goes to trust and credibility."

It was clear, though, that this was a consideration that could be managed by listening to the advice of the people at The Gathering.

"For Partners in Healing [the Elder] knew the guys and their level of commitment, judging who was ready based on experience." "Despite the risks, the benefits of having older people talk to younger people outweighs the risk."

The men also reiterated the need for offenders to face their own issues before they can help young people.

"There is a need to do work inside before going outside into the community."

Certainly these men came down on the side of youth-offender projects, seeing value in what the different generation can share and how the dynamic of differing ages can play out.

"Mixed talking circles are useful . [They] provide a forum to encourage those who are doing well. If there is a talking circle with people who are all the same age they may want to put up a front among their peers. If it is mixed ages people hear different perspectives, learn about different things .People are more apt to open up and talk about themselves and what is bothering them. It is a process where there is no preaching. There is sharing instead. This sharing may touch on similar experiences with others. This is feeling good about yourself. [It is] learning to be responsible for yourself. [It is] learning about the pleasure of giving and doing things for others."

It was clear that the men from Circle of Eagles supported youth offender projects.

"Guys can bring life experience to the table and give some insight into choices and consequences, the reasons for choices, irrational behaviour."

The poignancy of one of their comments sums up why youth-offender projects can be a positive force in the lives of all involved.

"Taking programs such as anger management and cognitive skills is good but there has to be a way to learn this without going to prison."

The Context

FAS

Many of the problems that Aboriginal youth must deal with point to maternal prenatal alcohol abuse. For this reason, a discussion of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) is a necessary part of any consideration of how these young people might be assisted by their communities. FAS and what used to be referred to as FAE (fetal alcohol effects) but is now more commonly termed ARDD (alcohol related developmental difficulties) can cause profound, if not always easily identified, difficulties that range from learning disabilities to habitual socially inappropriate behaviour.

Most children with FAS or ARDD have difficulty controlling impulses. This inability may show itself in inappropriate sexual behaviour, poor judgement in a range of other areas, or a frequent need of rule reminders. Such conduct often leads young people into conflict with the criminal justice system.

FAS and ARDD are the main preventable birth defects in Canada - and they are 100% preventable. Researchers note that even one episode of drunkenness in the third trimester of a pregnancy is enough to damage rapidly developing fetal brain cells. This means that maternal education and abuse prevention/recovery programs are doubly important.

In order to recognise the importance of early years in the long-term development of the individual, the Canadian government committed $2.2 billion in transfers to the provinces and territories (from 2000 to 2005) for the improvement of early childhood development programs. Because FAS/ARDD plays such a prominent role in health concerns for children an initiative to increase awareness and improve services to pregnant women was provided in a recent federal budget. Part of this initiative is a greater focus on assistance for Aboriginal families across the country. This aid is two-pronged in that it is meant to raise awareness as well as provide support for those already affected by FAS/ARDD. Further information about the kind of help available can be found by contacting Health Canada.

One of the difficulties in dealing with young people who have been disabled by maternal prenatal alcohol use is that they often have good expressive language skills. This is something that others use to judge intellectual abilities, however, because of the FAS/ARDD symptoms these young people function far below what is expected, based solely on appearances. Often both the youth and network of people that surround them are chronically frustrated because of unreasonable expectations that cannot be met.

Because FAS/ARDD disabled people present unique problems that are not always understood, those who work with young people need to be educated about the implications of this lifelong disability. Some healing lodges will not deal with FAS/ARDD disabled people because they do not have the resources - they should be made aware of the federal funding support to help them out (see earlier reference). Educating women that they must not drink during pregnancy has to be a priority for everyone in the community. Exploring a combination of mainstream and traditional healing for FAS/ARDD people is a way of showing them that they are unique in a positive way. Certainly, job-skills training appears to be more effective than formal education in allowing these people to become productive community members rather than unhappy participants in the criminal justice system.

In working with Aboriginal young people it is necessary to recognise the symptoms of FAS/ARDD and how best to deal with the young people who exhibit them. Although FAS/ARDD is life long it is not a sentence of worthlessness. With guidance both the people diagnosed with FAS/ARDD and those who live and work with them can channel their energies so that all involved feel less confounded by the disabilities and more reinforced by the unique qualities of the individuals who have them. This is an important lesson for offenders, Elders, organisations, and communities who will be involved in helping youth who are at risk.

The Literature

"From a research point of view, we should find out what are the things in common to young offenders so we know where our efforts at prevention will be most effective", said one participant at The Gathering.

In response to this suggestion we looked at a few studies that offer useful input in our consideration of this topic.

On May 10, 2000, a nation-wide One Day Snapshot of Aboriginal Youth in Custody was compiled by the Research and Statistics Division of the Department of Justice Canada. This research provides us with statistics that tell us where the youth lived before they committed their offences, where they committed their offences, and where they planned to relocate after being released from custody. Though such research is important so that government can know where to direct resources, it is equally important for the people on the frontlines to know where their energies are best utilised.

The data came from every province and territory in Canada. It came from cities, towns, and reserves. The youth were First Nations (75%), Metis (16%), Inuit (3%), and Inuvialuit (2%). Of the youth in the study 4% could not identify to which Aboriginal group they belonged. Young men made up the majority (82%) of offenders. The majority of the young people committed their offences in an urban setting; only 17% of offences were committed on reserve.

The study's findings of predominantly urban environments for the crime and a majority of male young offenders indicate that the programs that have been or continue to be in place are pointed in the right direction.

Another study (described in The Youth) was sponsored by Native Counselling Services of Alberta. In it, young people identify the things that made them turn away from crime. Certainly, learning to accept responsibility is central to what these young men had to say just as it was central to what the participants at The Gathering had to say.

It is also important to educate non-Aboriginal members of the community about Aboriginal traditions. Police will be more likely to take a co-operative rather than an adversarial approach if they understand the cultural significance of certain actions. The non-Aboriginal community as a whole may be more supportive if they understand why that support is needed.

"It is important to teach people about the medicines so that they are not misused."

It is equally important to ensure that members of the Aboriginal community, particularly the young people, have an understanding of the traditions and the medicines. Sometimes people who have been raised outside the Aboriginal communities need guidance because they have learned little about their culture. Such teaching not only guides their learning but it heals as it is taught.

This issue was raised at The Gathering. One participant noted: "We've got to concentrate on the traditional teachings and give kids time to gain those teachings."

In her groundbreaking book, Seen But Not Heard: Native People in the Inner City, Carol LaPrairie notes that it is the "interaction of certain factors that predict the degree of involvement in the criminal justice system". (LaPrairie, p.xiv) Such factors as length of time lived in the city (i.e. the longer - the more high risk) combined with a lack of education and employment skills gave people a greater vulnerability to conflict with the criminal justice system.

With regard to reserves, LaPrairie found that there was very little middle ground. Contrary to the myth of reserves being classless, she found that "people who live on them either do very well or very poorly, probably as a result of the concentration of power". (ibid, p.xiv) Participants at The Gathering might agree with her in this, but only in part, for many would say that grounding in the traditions is equally important in keeping people on the right path.

LaPrairie concludes, "The criminal justice system does not "fail" all Aboriginal people any more than it "fails" all non-native people. The problem is that it fails a much larger group of natives, for the simple reason that more are vulnerable to involvement in it." (ibid, p.xvii) This vulnerability is the result of factors such as substance abuse and a lack of education and job skills that, in turn, are the product of a wholly unsupportive environment. This is the point at which LaPrairie and the participants in The Gathering converge because it points to a deep and ongoing need for community development wherever that community exists, in either a rural or urban setting. Thus, in order to reduce the involvement of native people in the criminal justice system the intellectual/emotional/spiritual /physical needs of the population must be identified and addressed. And these needs must be addressed both in adults and children.

To follow on this theme is to argue, as others have in the past, that the idea of culture conflict, especially in the area of criminal justice, is simply a smoke screen for the core problems though it may intensify the difficulties that are already there. In a related area the opinions of those who participated in The Gathering and much of the academic literature are not in agreement. Some academic literature suggests that the entire question is one of socio-economic marginality whether one speaks of American blacks or Canadian Aboriginal people. Such a premise would not easily mesh with the idea put forth at The Gathering that healing can come from being in touch with and having a greater understanding of Aboriginal traditions.

Carol LaPrairie discusses a couple of beliefs that play a central role in criminal justice policy despite their inaccuracy. These beliefs are that most of the crimes committed by Aboriginal people take place on reserve and that all Aboriginal people are equally at risk of conflict with the criminal justice system. The former results from seeing First Nations and reserves as the same thing. The latter comes from seeing all Aboriginal people as a homogeneous group without the social and economic stratification that is a part of almost any sizeable collectivity. Such beliefs point government-led solutions in a direction which may not only be unproductive but may be harmful in the sense that while resources are focussed in a counterproductive direction the problems multiply at the source.

In Seen But Not Heard the tendency to see all Aboriginal people as the same is identified as a major impediment to effective social/justice policy. That is because the people with the greatest need are the least able to articulate that need whereas powerful Aboriginal political/lobby groups have agendas that seldom reach into the dark corners of this country's largest cities.

LaPrairie reports that virtually all of the most needy Aboriginal people were victims of some form, and frequently multiple forms, of abuse. Identifying abuse victims as high risk would lead to support for them before they encounter the criminal justice system. Part of the problem is that the people who understand the difficulties that young people and adults face do not want to face those difficulties themselves so they remove themselves from such an unhealthy and volatile environment as soon as they are able.

This point brings us full circle to the need for community development in that the healthier a community is the more people will want to stay. When such people stay they are in a better position to help those in difficulty to become healthier. So a former inmate will come to a community where he feels there is some support and may, in turn, become part of a program to keep young people from following the path that he took.

Negative actions are part of a chain reaction. Abuse may lead to emotional problems/inability to focus/poor education lead to poor job skills/substance abuse/lack of hope in a future lead to conflict with the criminal justice system. Nevertheless, the chain can be broken at more than one link and the more links that are broken the weaker it will be and the less chance there will be that the individual ends up in the criminal justice system. Or, as Carol LaPrairie says, "Society can create crime control and social problems 'industries' to deal with these issues after the fact, but it would be more humane, less costly and more efficient to prevent them from occurring in the first place". (Ibid, p.94)

Most ex-inmates told LaPrairie that it was better if they had solid support before they were released into cities. Such support can come in the form of programs inside the institution. Some programs, especially those dealing with Aboriginal traditions, have had success in assisting the brotherhoods and sisterhoods inside the institutions to achieve balance. Little, however, has been done to explore the possibilities of recruiting some of the more stable offenders to work with young people and keep them from making the same mistakes while, at the same time, helping these offenders, themselves, to heal.

The Corrections and Conditional Release Statistical Overview points out that the average age of admission of Aboriginal offenders is lower than for non-Aboriginal offenders. (CCRA Statistical Overview p.41) In addition, it states that the proportion of Aboriginal offenders incarcerated is higher than for non-Aboriginal offenders. (ibid, p.43) Together, these statistics seen in the light of Carol LaPrairie's analysis indicate the need to consider alternatives to what has been attempted to date. Perhaps, if Aboriginal youth can be reached at an earlier age there will be fewer Aboriginal adults in the Canadian penal system.

The Overview's statistic that 80% of federal Aboriginal offenders are serving a sentence for a violent offence (ibid, p.47) shows the urgency of the matter, especially given that the number of Aboriginal offenders in communities is increasing (Ibid, p.49). The latter statistic is probably due, at least in part, to the increase in the federal parole grant rate for Aboriginal offenders. (ibid, p.61) Such paroles can be highly successful if the offender has worked on his/her healing and the community to which he returns has a place for him.

The Conclusion

The people who gathered on the lands of the Goodstoney Nation in February 2002 came because they cared about making life better for their people, better for all people. I have used the word offenders throughout this book so that those reading it will understand of whom I am speaking, however, during The Gathering these men and women were referred to as relatives. The offenders were called relatives in recognition of belonging to the Aboriginal peoples across Canada and in recognition that they are human beings.

During those four days in February we came to understand that success is a relative concept.

"This brother was brought in for a horrendous crime. He just wanted to do his time to pay back society. Once inside he was introduced to our culture through Aboriginal programs and the seat lodge ceremony. In the programs, people are taught how to use their anger in a different manner. This brother did his correction plan. He totally turned his life around in the medium security institution so he was transferred to a minimum security institution. After spending months at the minimum with no institutional charges he got angry at a guard and was shipped back to medium. The brother said that he was only using the skills that he had learned in programming. When it came to my attention I said that he did well - in the past he would have taken the guard's head off.

"It is a very long journey to heal. When a brother has a hard time all the people involved in his healing journey should be called in a circle before there are any discussions to transfer an inmate to higher security. With this particular brother the system has spent many dollars through programming and got him to an incredible place in his life only to lose him because of an argument."

Where does the job of keeping young people out of the criminal justice system really start? It starts the same place everything else does - the beginning.

The Gathering was privileged to have a Cree Elder among its participants. While his words were not spoken in a language that all understood, their power was felt throughout the room. The following is a translation of what he said about children: "Our children are like the white poplar. They are affected by their surroundings. As they grow up they need to be taught good values. If the family and the community do not provide good role models children will look elsewhere."

No matter which nation people belonged to, the importance of raising children was one of their primary teachings.

"When we are inside our mothers a lot is set up and from birth to three a lot is also set up. If [the children] are around anger & abuse it's hard to change that. There is a lot of misunderstanding because people aren't looking at where we're coming from - as persons or as a people."

The participants at The Gathering understand, and they want the rest of the country to understand, that it takes time to heal. If you break your arm, it takes longer to heal it than it took to break it. A big part of that healing is learning to trust both on the part of the offender and on the part of the community to which he returns.

"Often it's hard for guys to earn the community's trust because of what they did. [The offenders] are good when they're sober but after they're out and they're not trusted then they fall back on old habits. Elders say that the reason you made a mistake is to learn something so keep trying."

"Ex-inmates should be given the opportunity to participate in something like a big brother or sister program because that would not [normally] be an option because of their offences."

When that trust is given it can have deeply positive results. The following is from a former inmate who has turned his life around and now works to make things better for both offenders and youth.

"When I applied for parole, I decided I wasn't going home to my addictions, I wanted to deal with them there. I was denied parole when I told the Board that. Shortly afterward I received a letter from a local detective saying that I should go back to my home community because they had enough of their own criminals here. I wrote him back and said that he could accept me here on parole or when I got out on mandatory release, but that I was staying here because only here could I learn to live with my own addictions. If I went home I would have to deal with my family's problems as well. The detective wrote back & said 'Welcome to [the community]. I carried those letters with me for a long time. Many years later we still stop and say hi on the street."

That this group discussed possibilities is not indicative that good programs do not currently exist. They do, though they are few and far between.

"Sometimes there are requests from schools. No one is chosen. They are simply told that there is a need. We try to teach responsibility, a kind of giving back of freedom - not like prison, which does the opposite of that. People make an application to come to [the healing lodge] as part of their need to find balance. Many good things happen at healing lodges and clients are always told before leaving that they may return to staff for support."

The folks at The Gathering said that if there were one thing that they hoped would come out of the process it would be that people would communicate better, especially between groups.

"A little while ago I was at a women's association meeting where we talked about the same issues as here yet we have a lack of communication with them."

Because of this need for better communication a diagram was drawn to show everybody what it would look like if all the healing circles in the country shared with each other so that there was one big circle. If they did it would look like this:

Image Description

The diagram above is of a group of small individual circles that form a circle which is surrounded by a larger circle which is also made up of small circles. The diagram was made to show participants what it would look like if all the healing circles in the country shared with each other so that there was one big circle.

"We need to all work together in a circle with inmates, Elders, case management team, community corrections, brothers and sisters, families and communities. Then we will have total understanding of where that spirit comes from. That way we can give that person the tools needed to heal himself in a spiritual, mental, physical, and emotional manner, so that spirit can return to the community, loving himself and, in turn, loving others. Once a relationship is formed the whole circle should be kept aware of what is happening to that brother or sister."

Can offenders help young people, to keep them from an unhealthy life? A former inmate said it best: "We've lived it. We've felt it. We've seen it. We can relate."

Bibliography

- Department of Justice Canada, Research and Statistics Division. A One-Day Snapshot of Aboriginal Youth in Custody. Department of Justice Canada (Ottawa, ON) 2002

- Finckenauer, James O. and Patricia W. Gavin. Scared Straight: The Panacea Phenomenon Revisited. Waveland Press (Prospect Heights, IL) 1999

- Gilman, Lawrence and Richard K. Milin. "An Evaluation of the Lifers' Group Juvenile Awareness Program". State Department of Corrections (Trenton, NJ) 1977

- LaBoucane-Benson, Patti. Getting Out and Staying Out: A Conceptual Framework for the Successful Reintegration of Aboriginal Male Young Offenders. Native Counselling Services of Alberta (Edmonton, AB) 2001

- LaPrairie, Carol. Seen But Not Heard: Native People in the Inner City. Department of Justice Canada (Ottawa, ON) 1994

- Latimer, Jeff, Craig Dowden, and Danielle Muise. The Effectiveness of Restorative Justice Practices: A Meta-analysis. Research and Statistics Division, Department of Justice Canada (Ottawa, ON) 2001

- McCue, Harvey. Strengthening Relationships Between the Canadian Forces and Aboriginal People. Department of National Defence Canada (Ottawa) 2000

- "Scared Straight: A Second Look". National Centre on Institutions and Alternatives (Washington, DC) 1979

- Schriml, Ron and Christine MacDonald. "Community Development Project: Final report". Prairie Justice Research Consortium, University of Regina (Prince Albert, SK) 1992

- Solicitor General Canada. Corrections and Conditional Release Statistical Overview. Solicitor General Canada (Ottawa) 2001

- Sullivan, Dennis and Larry Tifft. Restorative Justice: Healing the Foundations of Our Everyday Lives. Willow Tree Press (Monsey, NY) 2001

- Ten Plus Fellowship. "Save the Youth Now Group", S.T.Y.N.G./Ten Plus Fellowship (Bath, ON) 1980

*** Information about the Stone Path, Broken Wing, and Partners in Healing programs came from interviews with Susan Swan, Larry Smytaniuk, and Bruce Williams respectively

- Date modified:

PDF Version (72 KB)

PDF Version (72 KB)