Evaluation of the Collaborative Justice Project: A Restorative Justice Program for Serious Crime 2005-02

Table of contents

- Author's Note

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Evaluations of Restorative Justice

- The Collaborative Justice Project

- Method and Procedures

- I. The CJP Group: Measures and Procedure

- II. The Control Group: Measures and Procedure

- III. Participants

- Results

- I. Evaluation Participant Demographics and Offence Characteristics

- The CJP Study Groups

- The Control Groups

- II. Examination of the CJP Mandate: "Seriousness" of Cases

- III. Examination of the Research Questions

- a) Client Characteristics

- b) Program Activity

- c) Program Impact

- d) Value Added

- Discussion

- Victims Who Participate in Restorative Justice

- Offenders Who Participate in Restorative Justice

- Restorative Justice Diversity

- Participation in the CJP: Client Change and Impact

- Summary and Conclusions

- References

- Appendix A: Additional Information on Offender Matching (for all analyses except recidivism)

- Appendix B: Additional Information on Offender Matching (for all recidivism analyses)

Author's Note

This research project began in 1998, and as a result, the success of this evaluation is attributable to the efforts of a number of people. To begin, thanks goes to Jamie Scott, Andrejs Berzins , Lorraine Berzins, Robert Cormier, Rick Prashaw, Sheila Arthurs, and Renate Mohr, who, together, designed the program. Thank you to all our research assistants and colleagues who have assisted with various aspects of administration, data collection and data analyses: Jennifer Lavoie, Ian Broom, Jillian Emery, Jennifer Ashton, Rachna Mishra, Jennifer Topping, Terri-Lynne Scott, Shelley Price, Rebecca Jesseman, Guy Bourgon, Erik Gaudreault, Kimberley Smallshaw, and Jennifer van de Ven. Thank you also to Doreen Henley, who generously volunteered her time to assist with historical cases. Furthermore, this evaluation would not have been possible without the cooperation, assistance and dedication of the CJP staff, Jamie Scott, Jonathan Chaplan, Kimberly Mann, Marilou Reeve, Nancy Werk and Tiffani Murray. Lastly, the authors would like to thank the Crown Attorney's Office, specifically Andrejs Berzins and Louise Dupont, along with the Ottawa Police, who assisted in making this research possible. Without the commitment and perseverance of all these individuals, this project and the subsequent evaluation would not have been possible.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada. Correspondence concerning this report should be addressed to:

Tanya Rugge, Corrections Research,

Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada,

340 Laurier Avenue West,

Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0P8;

email: tanya.rugge@ps-sp.gc.ca.

Executive Summary

The Collaborative Justice Project (CJP) is a demonstration project running in the Ottawa area that employs a restorative justice approach in cases of serious crime. The CJP introduces a process that runs parallel to the legal justice system; a process that is designed to offer individual support to victims, assist the accused in taking responsibility for the harm caused, and provide parties with an opportunity to work together towards an appropriate resolution proposal. Criteria for acceptance into the program were as follows: (1) the crime was serious in nature, (2) at least one victim was interested in receiving assistance, and (3) the accused has accepted responsibility by entering a guilty plea and has indicated a desire to make amends. The CJP's program goal is to empower individuals affected by crime to achieve satisfying justice through a restorative approach.

The goals of this evaluation were threefold: (1) to determine whether a restorative approach can be applied in cases of serious crime at the pre-sentence stage of the criminal justice system, (2) to determine whether the CJP successfully met its mandate and program goals, and (3) to expand the empirical base regarding restorative justice research.

The evaluation sample consisted of CJP clients and a matched comparison group of offenders and victims. Specific outcome measures that were examined included whether program goals were met, whether clients' needs were met, whether clients were satisfied with the restorative approach compared to the traditional criminal justice system, and whether participation by offenders reduced their likelihood of re-offending. A quasi-experimental repeated-measures design was utilized.

The total sample of 288 evaluation participants consisted of 65 offenders and 112 victims in the CJP group and 40 offenders and 71 victims in the control group. Offenders were matched on gender, offence type, age and risk level. The majority of victims were in their thirties and forties, whereas offenders were younger, in their twenties. Most victims and offenders were Caucasian and employed. Over half of the offenders who participated in the CJP were first time offenders, with the majority of offenders being of low to medium risk. The crimes that were committed by these offenders were serious in nature, with three-quarters being person-based offences.

The evaluation examined four research areas: (1) client characteristics, (2) program activities, (3) program impacts, and (4) value-added. An examination of client characteristics revealed that client needs were diverse in nature, but there were commonalities between victims and offenders. Needs expressed by victims included the need to obtain information about the offence, hear the offenders' explanation, and communicate the impact the crime had on them. Offenders wanted to apologize, attempt to repair the harm caused, and provide an explanation for their criminal behaviour. Interestingly, only half of the cases resulted in a victim-offender meeting, suggesting a meeting was not always necessary for client needs to be met.

Assessing client characteristics also included examining attitudes, victim fear levels and offender remorse and accountability. The majority of victims who participated in the CJP felt that the court process was not always fair and just, a significant difference when compared with control group victims. There were no differences in fear levels between the two groups. The majority of CJP offenders were accountable and remorseful for their criminal behaviour, which was not surprising given that this was a criterion for acceptance into the program.

This evaluation examined various process elements. Most cases were referred from Judicial Pre-Trials, with the remainder being referred by defence lawyers, Crown attorneys, judges or others. CJP cases took approximately eight months to process. Reparation plans/agreements involved activities such as performing community service, providing restitution, attending treatment, attending school and maintaining employment. The court accepted the majority of agreements at the time of sentencing, though in most cases the judge added additional elements. Although most offenders were facing imprisonment at the commencement of the CJP, few received a custodial term at sentencing.

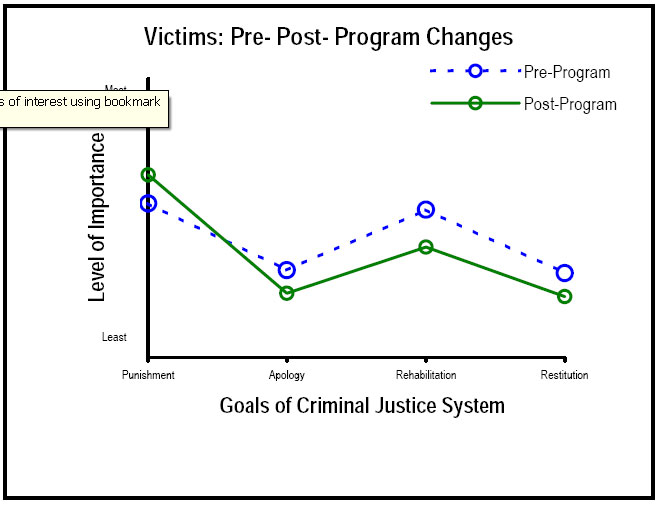

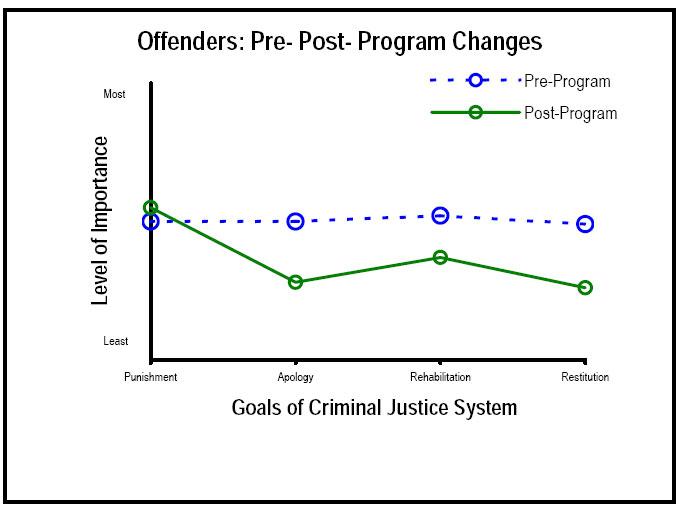

Pre-program to post-program participant change was examined to assess program impacts. There was little change over the course of the program, evidenced by no significant changes in offender remorse, victim fear levels, attitudes towards the criminal justice system and opinions of the importance of restorative goals.

To assess the added value of a restorative approach, CJP participants were compared to individuals who were processed through the traditional criminal justice system. The major difference between the two groups was in terms of client satisfaction. CJP participants were far more satisfied than control group participants. Offender recidivism rates were examined, and results suggested that the CJP had a small positive effect on recidivism, with CJP offenders re-offending at a lower rate than control group offenders over a three-year follow-up.

In conclusion, this evaluation found that a restorative approach can be successfully applied to cases of serious crime at the pre-sentence stage. Although additional research is needed to further explore many of the findings from this evaluation, results indicated that the program goal of empowering individuals affected by crime to achieve satisfying justice was attained.

Introduction

Restorative justice (RJ) is an alternative approach to criminal justice, as its philosophy, values and goals are distinct from the current system. Restorative justice focuses on restoration and healing rather than retribution and punishment. Although there is no single universally accepted definition, restorative justice has been defined as:

an approach to justice that focuses on repairing the harm caused by crime while holding the offender responsible for his or her actions, by providing an opportunity for the parties directly affected by a crime – victim(s), offender and community - to identify and address their needs in the aftermath of a crime, and seek a resolution that affords healing, reparation and reintegration, and prevents future harm (Cormier, 2002, p.1).

Canada 's current criminal justice system (hereinafter referred to as the traditional criminal justice system) is based largely on a retributive model that focuses on the offender, and the victim's role is reduced primarily to providing evidence. In addition, the community's involvement in ensuring justice, apart from the fact that trials are held in open court, is served indirectly through representations from the Crown and the judge. Dissatisfaction with this model of dispensing justice, particularly with respect to the exclusion of victims from the process, has led to a growth in restorative justice initiatives. In a restorative approach, the victim has an active role with the offender and the courts in achieving justice. Establishing guilt and assigning punishment for the offender are not the primary goals. The primary goals are taking responsibility, repairing the harm done to the victim and the community and facilitating healing.

The paths to healing and reparation are many and, in general, involve giving victims the opportunity to communicate to the offender how the crime has impacted them and what is needed in order for the harm to be repaired, to the extent possible. Reparation can occur through various means including face-to-face meetings, third party intermediaries and written communications. Steps to correct the harm can range from a simple apology to some form of restitution or community service. Which approach the victim chooses in communicating his or her questions and concerns and what the victim accepts as an offer of reparation by the offender is controlled entirely by the victim.

Evaluations of Restorative Justice

In recent years, many restorative justice programs have been developed and are currently being delivered by a variety of agencies and organizations in Canada . Restorative justice programs are delivered by the police (Chatterjee, 1999), paroling authorities (elder-assisted parole hearings; Vandoremalen, 1998), probation services (Bonta, Wallace-Capretta, Rooney, & McAnoy, 2002) and community volunteers and agencies (Wilson & Picheca, 2005). Furthermore, the victims and offenders in these programs range from the very serious (e.g., sex offenders and their victims; Wilson & Picheca, 2005) to the less serious (e.g., Nuffield, 1997). Most restorative justice programs in Canada , and internationally, appear to target low-risk offenders who have committed non-violent crimes (Bonta, Jesseman, Rugge, & Cormier, in press). Some projects are large, encompassing entire jurisdictions (e.g., Department of Justice, Nova Scotia , 1998) while many others are small, local initiatives. Despite the prevalence of restorative justice programs, few have been evaluated.

One of the most important goals of restorative justice is to promote healing and reparation between the victim and the offender. However, most evaluations of restorative justice have focused on restoration of the victim (Latimer, Dowden, & Muise, 2001). In this respect, the findings are overwhelmingly positive with victims reporting very high satisfaction rates (Braithwaite, 1999) although these findings are tempered by a self-selection bias. Equally important, some would argue, is offender reparation (Bazemore & Dooley, 2001). Offender reparation involves taking responsibility for the harm caused and preventing future offending. This latter outcome is extremely important to a general public that expects the criminal justice system to reduce the likelihood of re-victimizations.

For the most part, evaluations of restorative justice have focused on victim satisfaction outcomes and, to a lesser extent, offender recidivism. Other outcomes such as reductions in fear of crime and increased respect for criminal justice systems are rarely reported and only anecdotally. Often researchers have attempted to answer the questions “for whom does restorative justice work best?” and “why does it work?” through qualitative, unstructured methodologies. These methodologies are well suited for exploratory investigations and an understanding of what happened in a particular circumstance or restorative justice program, but due to the relative vagueness of reporting and interpreting observations they have limited generalizability. Quantitative, highly structured evaluation methodologies are needed to increase our ability to identify what works and for whom. The present study includes structured data collection methods augmented by qualitative, open-ended methods.

The Collaborative Justice Project

The Collaborative Justice Project (CJP) began as a demonstration project of the Church Council on Justice and Corrections in 1998. Supported by the Crown Attorney's office, the CJP was based in the Ottawa Courthouse ( Ontario ) to provide on-site service and have access to court processes and case files. Funding for the program came from Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada (the former Solicitor General Canada ), Justice Canada , Correctional Services Canada, as well as the National Crime Prevention Centre and the Trillium Foundation.

The CJP intended to focus on “cases in which the accused is facing serious criminal charges that would normally result in a significant term of imprisonment” (Funding Proposal, 1998). Cases could be referred by the judge, the Crown, the defence, probation, or even by the offender himself/herself. There was no restriction as to when the referral could be made, although it was expected that most referrals would come before a formal plea was presented to the court. Upon referral, the CJP staff would meet with the accused to ensure that the accused was willing to accept responsibility for the crime and once satisfied, staff would then contact the victim to invite their participation. Three criteria had to be met for a case to be accepted into the CJP: (1) the crime had to be serious (i.e., the offender was facing imprisonment), (2) at least one victim was interested in receiving assistance from the CJP, and (3) the offender accepted responsibility (i.e., usually signified by entering a guilty plea) and indicated a desire to attempt to repair the harm caused by his or her behaviour.

Once the case was accepted by the CJP, the courts would adjourn the case, allowing time for the CJP process to take place. Once the process had concluded, the CJP would report back to the court, either submitting a reparation plan or indicating that their process had concluded. In cases where no resolution agreement was reached, the CJP only indicated that their process was complete so as not to influence the resuming court process. The restorative process of the CJP was unique, as it ran parallel and in conjunction with the current system. In essence, the case was removed temporarily from the traditional criminal justice system and placed on a parallel restorative track and then returned to the traditional criminal justice system for sentencing, taking into consideration any reparative outcome.

The goal of the CJP was to offer participatory mechanisms through which the victim, the offender, and affected community members could work together to develop resolution plans that repaired, to the extent possible, the harm caused by the offence. The CJP was based on three key themes: support, accompaniment and empowerment. Project staff worked with both the victim and the offender to provide support, to explore the impact of the crime, to identify resulting needs, and discuss various mechanisms they might utilize to collaborate on a resolution plan. One important mechanism to fulfill these needs was to provide the option of a face-to-face meeting with the victim(s), the offender(s), their social supports and engaged community members (e.g., community volunteers, police officer, probation officer). These face-to-face victim-offender meetings provided a venue for victims to describe the impact of the crime on them, for offenders to take responsibility, and for all involved to formulate plans for repairing the harm in a resolution plan. Where victims or offenders chose not to participate in a face-to-face meeting but were interested in receiving support, the CJP staff would work with them to explore indirect mechanisms for reparation and healing.

At program commencement, the CJP team consisted of one and one half full-time positions. By the second year, the number of positions increased to three and one half, with three caseworkers (also referred to as facilitators), one of which was the Program Director, and a community liaison staff person. During the first six years of operation, the program has had six different caseworkers, and averaged three full-time staff per year. Over this time, funding provided for a minimum of two to a maximum of three and one half full-time positions. Caseworkers required previous mediation experience and subscribed to a “certain philosophical outlook”, meaning that their perspective on life incorporated restorative values. Four caseworkers also had victim-offender mediation experience and two caseworkers had prior counselling experience. When extensive experience was not present, on the job training was emphasized. All but one of the CJP caseworkers possessed a university degree (one in theology, one in social work and three in law (L.L.B.)).

An advisory circle was incorporated into the original project development plan. The advisory circle met monthly and was equally comprised of traditional criminal justice system professionals (e.g., Crown attorneys, defence attorneys, police officers, victim witness program staff, etc.), and those involved in community services (e.g., psychologist, social worker, addictions professional, immigration/refugee lawyer, etc.). The main purpose of the advisory circle was to afford the CJP staff access to a broad range of perspectives both within the traditional criminal justice system context and beyond. More specifically, the advisory body was used (1) as a consultation group for reviewing cases and seeking advice, (2) to provide assistance in accessing community services or in brainstorming creative responses to criminal justice system challenges, and (3) to act as liaisons within their own communities by educating their colleagues and constituents about the CJP program and its goals.

After a developmental phase that established general procedures and mechanisms for accepting referrals to the CJP, an evaluation framework was developed in 1999. Researchers worked with the CJP staff to establish the general parameters of the evaluation. Four key areas were identified for investigation: (1) provide a comprehensive assessment of the clients served by the project; (2) describe the activities that occurred to meet the needs of the clients; (3) record the reactions of clients and other key criminal justice actors to these activities; and (4) assess the value added by a restorative justice approach. This report addresses these key areas.

Method and Procedures

The evaluation design involved two main groups of participants, the CJP group and a control group. The control group was divided into two subgroups: (1) victims and offenders who were invited to participate in the CJP but who decided not to and (2) victims and offenders who had no contact with the CJP and who were processed through the traditional criminal justice system. Victims and offenders were matched on a set of pre-selected variables. Participation in the research was strictly voluntary. Data collection for the CJP group began in the fall of 1999 and concluded in the spring of 2003. Other aspects of the evaluation occurred in 2003, and the control group data was gathered in the summer of 2004.

I. The CJP Group: Measures and Procedure

Evaluation measures were designed to accommodate various levels of participation involvement (e.g., partial involvement, information exchange, meeting, etc.). The types of services provided were based on participant's individual needs, and as a result, not all cases resulted in a victim-offender meeting. Also, t he evaluation procedure was customized depending on the respondent, victim or offender. The following evaluation measures were administered to the CJP group participants:

General Opinion Survey : Participants completed this self-report pre-measure privately, sealed it in an envelope and either chose to return it to their facilitators to be forwarded to the researchers or mailed it directly to the researchers. This brief questionnaire asked participants about their opinions regarding the traditional criminal justice system. For offenders, the questionnaire consisted of six questions, and for victims, eight questions (additional questions related to fear and safety).

The Level of Service Inventory – Revised (LSI-R) : Researchers scheduled an interview with offenders as soon as they agreed to participate in the evaluation. The purpose of this interview was to administer the LSI-R to obtain demographic information, criminal history, information on other risk factors and a level of risk determination. The quantitative 54-item LSI-R is a validated, structured risk-need assessment instrument designed for use with offenders who are 16 years and older (Andrews & Bonta, 1995).

Pre-Meeting Questionnaire : If a victim-offender meeting, or circle, took place, a nine-item, paper-and-pencil, pre-measure was administered to victims and offenders just prior to the meeting or circle. The same method of administration was used as for the General Opinion Survey. Participants were asked about their feelings towards the other party (victim was asked about offender, offender was asked about victim), their current needs, and their goals in relation to the meeting or circle.

Post -Program Interview: Approximately two weeks after sentencing, and once the case was considered closed by the CJP staff, researchers contacted participants to schedule post-program interviews. Originally, this interview took place in person; however, when participants expressed a preference for a telephone interview, accommodations were made. This 45-minute interview consisted of 62 questions for offenders (with an additional nine questions for young offenders) and 63 questions for victims. Participants were asked questions regarding their attitudes and perceptions (e.g., about the restorative justice process, the traditional criminal justice process, etc.), their experience with the CJP program and its processes (e.g., whether they felt their needs were met, their opinions about the offender's reparative efforts, etc.), their perceptions of fairness and satisfaction (e.g., most satisfying aspects, most difficult aspects, etc.), their perceptions of fear (e.g., life changes since the crime, thoughts about the likelihood of offender re-offending, etc.), information about the offence (e.g., injury, loss, etc.), and past victimization incidents.

In addition to the measures for victims and offenders, a Case Completion Facilitator Interview was conducted. Facilitators were asked case-specific questions regarding their opinions of the case, challenges they may have encountered, and their thoughts on the benefits of the process for each participant.

Facilitators were also asked to complete Assessments for each evaluation participant, at three different time intervals. Assessments 1, 2 and 3 were questionnaires that asked facilitators to record a range of information (e.g., personal-demographic and offence information (Assessment 1 only), the client's needs and strategies to meet these needs, and reparation activities, etc.). Assessments were completed at case commencement, mid-way through process, and at case completion. Also upon case completion, researchers conducted extensive File Reviews on each client. Demographic information was recorded, as well as the particulars of the CJP process (e.g., number of contacts, meetings, whether there was a victim-offender mediation or circle, etc.).

Lastly, Key Player Interviews were conducted with community volunteers, Crown attorneys, defence attorneys, judges and other individuals who had information regarding the CJP. These 20-minute interviews, conducted by researchers in person or over the phone, posed questions regarding the CJP program, and participants' attitudes toward and experiences with restorative justice and the traditional criminal justice system.

Procedure for CJP Group: Typically, cases were referred to the CJP at the Judicial Pre-Trial (JPT), by the defence, the Crown or the judge. A JPT is an informal meeting where the Crown, the defence lawyer, the judge and the investigating police officer discuss the case, the evidence, possible resolutions, and potential trial issues. During the course of the JPT, the Crown, defence and judge may, collectively, decide to refer the case to the CJP. Occasionally, victims and/or offenders would approach program staff directly to obtain information about the program. In most cases, staff spoke with offenders initially, to determine appropriateness, before contacting the victim(s) to assess their willingness to participate. Even if a victim approached the program, the CJP staff would determine appropriateness before proceeding.

Once the offender was deemed appropriate, CJP caseworkers would contact the victims, explain the project and request their participation. If at least one victim agreed to participate, the case would proceed. At this point, voluntary participation in the evaluation was introduced and once consent was given, the participants completed the General Opinion Survey. Researchers met with offenders to administer the LSI-R. The pre-meeting questionnaires were distributed by CJP caseworkers, and once the case was completed, the researchers conducted the post-program interviews either in person or over the phone.

Data collection for the evaluation started approximately one year after the CJP program began. As a result, 10 cases were either completed or underway when the evaluation began. Although not all evaluation measures could be administered, participants in these “historical” cases were contacted and asked to participate in the post-program interview. In other cases, only the post-program interview was conducted because researchers were either not informed about these cases until after a victim-offender meeting occurred or, participants originally chose not to participate in the evaluation but decided to offer their opinions in the post-program interview. As a result, these post-program interviews were combined with the historical cases and together resulted in a larger sample size for post-program interview questions.

Recidivism: The final step of the evaluation involved reviewing the RCMP's criminal history records to determine whether or not offenders re-offended within a three-year follow-up period. Insufficient time has passed to allow for a follow-up of the control group offenders, as data was collected in July 2004 and many of these offenders are still incarcerated. Once these offenders are released, and the follow-up period (of at least one year) has passed, a recidivism examination will occur. However, a comparison sample of offenders selected from a large database was used to compare the recidivism rates of this sample to the CJP offenders in this study.

II. The Control Group: Measures and Procedure

Two comparison sub-groups were constructed. The first comparison group (the minimally served control group) consisted of victims and offenders who (a) met the CJP criteria and (b) were approached to participate but who declined. In the case of victims, this meant they did not wish to participate in the CJP while for offenders, it meant either (a) they were minimally served by the program, and decided not to continue with the CJP, or (b) they met the criteria and were willing to participate however the victim(s) in their case did not wish to participate. This minimally served control group was designed to allow for an assessment of whether persons who agree to participate were different from those who did not.

The second comparison group (the traditional control group) consisted of victims and offenders who were not approached by CJP staff. These cases were processed through the traditional criminal justice system. Within this comparison group, offenders who had pled guilty were matched on offence type, age, gender and risk level, and the victims in their cases were compared.

The measures for all control groups were similar. In the 43-question interview, control group victims and offenders were asked to share information on demographics, current offence, attitudes on the traditional criminal justice system and restorative justice, and if they had any contact with the CJP. Control group victims were also asked questions about past victimization, their fear of crime, and experiences with victim services. In addition, the Level of Service Inventory - Screening Version (LSI-SV; Andrews & Bonta, 1998) was administered to control group offenders in order to assess their risk level. The LSI-SV consists of eight domains of the original LSI-R: criminal history, education/employment, companions, alcohol/drug problems, personal/emotional problems, family/marital problems and attitudes/orientation, coded as “yes/no” or on a “0-3” scale. Psychometrics properties of the LSI-SV are well established (Andrews & Bonta, 1998).

Procedure for Control Group: The procedure for the two victim control groups was different. Minimally served control group victims' names were provided by the CJP staff and these individuals were contacted by the researchers and interviewed over the telephone. The traditional control group victims' names were linked to the control group offenders that were identified. These victims were first contacted by the Ottawa Police who requested permission from the victims for researchers to contact them.

Obtaining a sufficient sample size for the offender control groups was challenging. In many cases, offenders could not be reached or were unwilling to participate. As a result, the minimally served offender control group was so small that statistical analyses were not possible. Data collection for offenders who were processed through the traditional criminal justice system was also difficult. Researchers were assigned to the “ Guilty Plea Court ” at the Ottawa Courthouse for a six-month period to identify appropriate cases. Court dockets were reviewed each morning to identify appropriate cases and researchers attended court to ensure that a guilty plea was indeed entered. Offenders were approached regarding the study as they left the courtroom. If an offender was identified in the court docket review, the names of victims were also identified. Therefore, the victims were directly linked to the offenders that were identified. These names were then provided to the Ottawa Police who contacted the victims and requested permission for researchers to contact them.

In order to obtain a sufficient number of control group offenders, researchers also identified appropriate offenders who had already been sentenced. Because offenders in the CJP were facing incarceration, researchers contacted local institutions to review their files. Files and Daily Rosters at the Ottawa-Carleton Detention Centre and the Central East Correctional Centre in Lindsay , Ontario were reviewed for potential matches. Cases of robbery and assault were relatively easy to match, but cases of driving offences that resulted in bodily harm or death were extremely difficult to locate due to the low incidence rate. Researchers travelled to the institutions and interviewed these offenders.

III. Participants

The CJP Group Participants: Although an attempt was made to complete all evaluation measures for every CJP client (victims and offenders), this was not always possible. Since participation in the CJP and the evaluation was voluntary, some victims chose not to participate in the program and some who became involved with the CJP chose not to participate in the evaluation. The CJP criteria consisted of three criterion: (1) the crime is serious in nature (i.e., the offender is facing imprisonment), (2) at least one victim is interested in receiving assistance from the CJP, and (3) the accused accepts responsibility for the offence (i.e., a plea of guilty is entered) and indicates a desire to make amends for the harm caused. Correspondingly, the CJP group victims consisted of individuals who were victims of serious crime (directly or indirectly) and who agreed to participate in the CJP program and the evaluation. For offenders, they had perpetrated a serious crime, had pled guilty (in most cases), were facing a term of imprisonment upon conviction and demonstrated actions suggesting they were accepting responsibility. The evaluation required participants to voluntarily consent, and in most cases they needed to be over the age of 16 years. In cases where participants were under the age of 16 years, permission was sought from the parents and the youth. All participants, victims and offenders, were over the age of 12 years.

The Control Group Participants: Given that all control group participants were matched on offence type, all victims in the control group were victims of a serious crime and voluntarily consented to the evaluation. Control group offenders had committed a serious crime and had pled guilty. However, there was no assessment of their acceptance of responsibility level for their crime in order to be included in the control group. Although efforts were made to obtain young offenders to match to the CJP group, only adult offenders were obtained.

Results

From the beginning of the CJP (September 1998) to the end of the evaluation period (December 2002), program staff contacted 676 individuals (230 offenders and 446 victims), informing them about the CJP and requesting their participation. For the purposes of this research, participation was categorized into three levels: Level 1, No Participation; Level 2, Minimal and/or Discontinued Participation; and Level 3, Full Participation. Minimal participation (Level 2) was defined as one round of communication (the victim would request information, the CJP staff would obtain the information from the offender and then contact the victim to relay the information). If the information loop continued beyond one round, the case was categorized as Level 3 participation. Level 3 participation could take the form of shuttle mediation (i.e., information exchanges as just described), a written letter of apology to the victim by the offender, or a face-to-face meeting.

Of the 230 offenders contacted, almost half (44.8%) fully participated in the program. Of the 446 victims contacted, 38.8% fully participated and 8.5% participated to a lesser extent, receiving information or support. Of the 173 victims who fully participated in the CJP, 52.0% of these victims had a face-to-face meeting with the offender. When examining the participation rates, it is important to note that of the 446 victims approached, 45.5% (203/446) declined to participate in the CJP (25.6% (n = 114) declined directly to CJP staff and 20.0% (n = 89) declined indirectly by not responding to contact attempts). Reasons for declining participation were examined and are presented later in this report. Additional information regarding CJP participation rates is presented below in Table 1.

Table 1. Participation Rates and Outcomes in the CJP (N = 676)

Group |

Level of Participation (%, n) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

Level 1 |

Level 2 |

Level 3 |

|

Victims |

52.7% (235) |

8.5% (38) |

38.8% (173) |

|

Within Level 1: |

Within Level 2: |

Within Level 3: |

Offenders |

49.1% (113) |

6.1 % (14) |

44.8% (103) |

|

Within Level 1: |

Within Level 2:

|

Within Level 3: |

I. Evaluation Participant Demographics and Offence Characteristics

The CJP Study Groups: Although an attempt was made to include all of the victims and offenders contacted by the CJP (N = 676, as presented in Table 1) in the evaluation, the final sample included 65 offenders and 112 victims. Since the evaluation was voluntary, participants occasionally chose to participate in only some of the measures or chose not to answer questions; therefore, many cases have missing data. Also, in some cases, operational difficulties hindered the administration of the pre-measure and pre-meeting questionnaires, and in other cases, contact could not be made with participants at the post-program stage as their contact information was no longer valid. Data presented from this point forward is based on this sample of 65 offenders and 112 victims.

The majority of victims and offenders who formed the CJP groups fell into the full participation category. Ninety-two percent of victims (n = 103) fully participated in the CJP program (based on the criteria presented above) and 8.0% (n = 9) participated minimally. For offenders, 89.2% (n = 58) of offenders fully participated in the CJP, and 10.8% (n = 7) participated to a lesser extent, mostly because the victims chose not to fully participate.

Personal-demographic information on offenders and victims who participated in the CJP evaluation are presented in Table 2. Of the 65 offenders, over three-quarters (76.9%) were adults (n = 50); the remainder were young offenders (n = 15). The age of the offenders ranged from 15 to 63 years at the time they were referred to the program with an average age of 27.4 years (SD = 11.0). The majority of offenders (69.2%) were under age 30 whereas the majority of victims (77.7%) were over age 30. Victims' ages ranged from age 11 to 77 years with an average of 39 years (SD = 12.9). Analyses of these demographic characteristics showed that the CJP and comparison groups were not significantly different across marital status, race, and educational level. Furthermore, there were no significant differences between the two groups on the matching variables (gender, offence type, age and risk level), with the exception of gender, with there being significantly more males than females in the victim control group (see Appendix A).

The Control Groups : In order to obtain a sufficient sample, a total of 442 individuals (270 offenders and 172 victims) were identified. All victims were identified either through the review of court dockets or by the CJP. Offenders were selected for the control group if they could be matched on offence type, gender, and age. Of the 270 offenders, 257 were identified for the traditional control group (no contact with the CJP) and 13 for the minimally served control group (minimal contact with the CJP). It was difficult to obtain a larger sample of the minimally served offender group, as the CJP staff tried to work with every offender who requested their services. As a result, many offenders were no longer only “minimally served”.

Of the 257 possible control offenders identified for the traditional control group, interviews were obtained with only 54 offenders. Thirty-seven of these offenders were selected through the court dockets and 17 by reviewing institutional files. Of the 13 offenders in the minimally served control group (identified by the CJP), only two agreed to participate in the evaluation. As a result, no analyses could be conducted on this group. Of the 172 victims, 109 were identified for the traditional control group and 63 for the minimally served control group. Forty-two traditional control group victims and 29 minimally served control group victims agreed to participate in our interview. Of the 442 individuals identified, approximately 43% of victims and 67% of offenders could not be contacted. Of those contacted, 45% of victims and 4% of offenders declined participation in the evaluation.

Table 2. Personal-Demographic Characteristics of the Evaluation Participants (%, n)

|

CJP Participants |

Control Group Participants |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Characteristic |

Offenders |

Victims |

Offenders |

Victims |

|

|

n = 65 |

n = 79-112* |

n = 40 |

n = 69-71* |

|

Age: |

Under 18 |

10.8 (7) |

8.4 (9) |

5.0 (2) |

7.2 (5) |

18-29 |

58.4 (38) |

10.3 (11) |

65.0 (26) |

29.0 (20) |

|

|

30-39 |

15.4 (10) |

33.6 (36) |

12.5 (5) |

21.7 (15) |

|

40-49 |

10.8 (7) |

32.7 (35) |

15.0 (6) |

26.1 (18) |

|

50 and over |

4.6 (3) |

15.0 (16) |

2.5 (1) |

15.9 (11) |

Offender Status: |

Adult |

76.9 (50) |

- |

95.0 (38) |

- |

Youth |

23.1 (15) |

- |

5.0 (2) |

- |

|

Gender: |

Male |

89.2 (58) |

51.8 (58) |

90.0 (36) |

70.4 (50) |

Female |

10.8 (7) |

48.2 (54) |

10.0 (4) |

29.6 (21) |

|

Race: |

Caucasian |

73.8 (48) |

91.1 (102) |

72.5 (29) |

81.7 (58) |

Aboriginal |

3.1 (2) |

0.0 (0) |

5.0 (2) |

0.0 (0) |

|

|

Black |

4.6 (3) |

2.7 (3) |

10.0 (4) |

0.0 (0) |

|

Other/ Unknown |

18.5 (12) |

6.3 (7) |

12.5 (5) |

18.3 (13) |

Education: |

Less than grade 12 |

50.9 (29) |

26.5 (9) |

65.0 (26) |

21.4 (15) |

High School Diploma |

38.6 (22) |

20.6 (7) |

25.0 (10) |

28.6 (20) |

|

|

College/ University |

10.5 (6) |

52.9 (18) |

10.0 (4) |

50.0 (35) |

|

Unknown |

-- (8) |

-- (78) |

-- (0) |

-- (1) |

Employed/Student: |

Yes |

75.4 (49) |

87.3 (69) |

65.0 (26) |

90.1 (64) |

No |

24.6 (16) |

12.7 (10) |

35.0 (14) |

9.9 (7) |

|

Marital Status: |

Single |

67.7 (42) |

34.3 (37) |

70.0 (28) |

48.6 (34) |

Married/ Common-Law |

22.6 (14) |

53.7 (58) |

17.5 (7) |

42.9 (30) |

|

|

Separated/ Divorced/ Widow |

9.7 (6) |

12.0 (13) |

12.5 (5) |

8.5 (6) |

|

Unknown |

-- (3) |

-- (4) |

-- (0) |

-- (1) |

Previously Victimized: |

Yes |

58.5 (24) |

63.5 (47) |

35.0 (14) |

47.1 (33) |

|

No |

41.5 (17) |

36.5 (27) |

65.0 (26) |

52.9 (37) |

Unknown |

-- (24) |

-- (38) |

-- (0) |

-- (1) |

|

Previous Experience |

Yes |

10.0 (4) |

8.9 (4) |

5.0 (2) |

11.8 (8) |

with RJ: |

No |

90.0 (36) |

91.1 (41) |

95.0 (38) |

88.2 (60) |

|

Unknown |

-- (25) |

-- (67) |

-- (0) |

-- (3) |

Notes. *The n for CJP victims ranged from 79 to 112 and the n for control victims ranged from 69 to 71, depending on missing data.

For CJP participants, age was unknown for five victims and employment status was unknown for 33 victims. For control group participants, age was unknown for two victims.

The high number of “unknown” is the result of some of this data not being collected directly from the participants in the first two years of the evaluation.

Although data was originally collected on 54 offenders for the traditional offender control group, only 40 offenders could be matched on all variables. Analyses confirmed that there were no significant differences on the matching variables (gender, offence type, age, and risk level) between the two groups (see Appendix A for further information).

Examining dispositions, 60.0% of offenders in the matched control group received a custodial sentence. Sentences ranged from 14 days to two years in length, with the average time being 245 days (M = 245, SD = 183.3). Probation was given to 74.1% of the sample (some offenders received a custodial sentence followed by probation). The remainder received a variety of dispositions (e.g., fines, suspended sentences, etc.).

The control group victims (see Table 2) were slightly younger than the victims who chose to participate in the CJP; however, the differences were not statistically significant. Significant differences between the two groups were found across gender ( c 2 (1, N = 183) = 8.74, p < .01) with the comparison group comprised of a higher percentage of males (70.4%) than the CJP victim group (51.8%). Also, fewer control group victims (47.1%) reported being previously victimized than CJP victims (63.5%), a difference that approached statistical significance ( c 2 (1, N = 46) = 3.45, p = .06). Lastly, a greater percentage of control group victims (30.0%) than CJP victims (15.2%) knew their offender prior to the crime; however, this difference was not significantly different.

For victims in the minimally served victim control group, it was important to identify reasons as to why these victims declined participation in the CJP. A total of 19 victims responded to this question. Nearly a third of victims (31.6%, n = 6) felt that they had dealt with the incident and had no need to revisit it, 26.3% (n = 5) felt anger and had no desire to communicate with the offender, 15.8% (n = 3) saw “no point” in participating, another 15.8% (n = 3) cited the time and energy that would be involved, and 10.5% (n = 2) indicated that they were “not ready” to meet the offender at the time they were contacted.

Independent samples t-tests were conducted to examine whether victims who declined participation in the CJP (the minimally served victim control group) were significantly different from victims who were not contacted by the CJP (the traditional victim control group), on their attitudes, perceptions, and fear of crime. When alpha was adjusted using Bonferroni's correction technique (critical alpha = .05/11 = .004), no comparisons between the two groups were significant. As a result, further analyses conducted using victim controls combined the minimally served victim control group and the traditional victim control group into one victim control group (see Figure 1).

The decision to combine these two groups was made after some deliberation. There are reasons to believe that the minimally served group and the traditional comparison group may not be initially equivalent. For example, the minimally served group was given the opportunity to participate and eventually refused. On the other hand, the traditional comparison group was not given this opportunity to participate, and would, therefore, contain both potential participants and potential refusers. Ultimately, the decision to combine the groups was influenced by (a) the need to maximize sample size and by (b) the absence of significant differences between the two victim control groups on attitudinal and fear variables.

Figure 1. Control Group Breakdown

Control Group Type |

Offenders |

Victims |

|

|---|---|---|---|

(1) Minimally Served Control Group |

Offenders motivated to participate in the CJP but were not able to as their victims did not wish to participate Insufficient sample size, no analyses conducted |

Declined participation in the CJP n = 29 |

The two victim control groups were combined for all analyses (N = 71) |

(2) Traditional Control Group |

Experienced the traditional criminal justice system (matched on offence type, gender, age and risk level) n = 40 |

Experienced the traditional criminal justice system (victims of the offenders in the box to the left) n = 42 |

II. Examination of the CJP Mandate: "Seriousness" of Cases

The majority of offenders who participated in the CJP were involved in offences against the person (70.8%). Twenty percent (20.0%) of offenders were involved in property crimes and 9.2% were involved in Criminal Code traffic based offences. Most of the index offences (for which offenders were referred to the CJP) were serious in nature: robbery (26.2%), assault or assault causing bodily harm (26.2%), sexual offences (3.1%), and dangerous driving or impaired driving causing bodily harm or death (21.5%). Further information is presented in Table 3.

The factor that makes the CJP unique is that it applies a restorative approach at the pre-sentence stage to cases of serious crime. A review of the index offences shows that the majority of crimes committed by the CJP offenders were serious in nature (Table 3). However, a serious crime was operationally defined as “the offender was facing imprisonment”. To explore further this operational definition, the Crown's position on sentencing was examined. Unfortunately, the Crown's original sentencing position was available for only 12 of the 65 offenders. In these 12 cases, the Crown was seeking a term of imprisonment in 58.3% of these cases (n = 7). As a result of the small sample size, interpretation is limited. It is important to note that over half of the offenders who participated in the CJP were first-time offenders (58.5%, n = 38).

Another way of examining the seriousness of cases is to assess the offender's likelihood to re-offend. Therefore, an examination of the LSI-R scores was conducted to determine the risk levels of the offenders who participated in the CJP. LSI-R scores were available for 34 offenders. For the other 31 offenders, LSI-SV scores were tabulated through file reviews. LSI-R scores ranged from 2 to 43, with a median score of 12.50 (M = 16.24, SD = 10.20). LSI-SV scores ranged from 0 to 8, with a mean score of 3.32 (SD = 2.23). Overall, 47.7% of offenders scored either below 13 (LSI-R) or 2 (LSI-SV), categorizing them as low-risk. Thirty-seven percent (36.9%) of offenders were categorized as medium risk and only 15.4% of offenders were at a high risk to re-offend. Consequently, although many of these offenders had committed serious crimes, almost half of them were categorized as a low risk to re-offend.

At the commencement of the program, facilitators were asked to rate whether they felt the offender was genuinely remorseful (yes, somewhat, unsure, no). As all offenders needed to demonstrate some remorsefulness to be accepted into the CJP, it was not surprising that no offenders were coded as unremorseful. Facilitators' perceptions on remorsefulness and accountability are further examined later in this report.

Table 3. Index Offence, Disposition and Risk Level Characteristics (%, n)

Characteristic |

CJP Offenders |

Matched Control Group Offenders |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

n = 65 |

n = 40 |

|

Type of Index Offence: |

Person |

70.8 (46) |

47.5 (19) |

Property |

20.0 (13) |

27.5 (11) |

|

Driving |

9.2 (6) |

25.0 (10) |

|

Most Serious Index Offence: |

Robbery |

26.2 (17) |

17.5 (7) |

Assault CBH/Weapon/Aggravated |

20.0 (13) |

15.0 (6) |

|

Sexual Assault/Indecent Assault |

3.1 (2) |

0.0 (0) |

|

Assault |

6.2 (4) |

15.0 (6) |

|

Dangerous Driving/CBH/Death |

16.9 (11) |

15.0 (6) |

|

Impaired Driving CBH/Death |

4.6 (3) |

10.0 (4) |

|

Property |

20.0 (13) |

27.5 (11) |

|

Other |

3.1 (2) |

0.0 (0) |

|

Disposition:* |

Custody |

16.9 (11) |

60.0 (24) |

Conditional Sentence |

46.2 (30) |

5.1 (2) |

|

Suspended Sentence |

12.3 (8) |

5.1 (2) |

|

Probation |

83.1 (54) |

74.1 (20) |

|

Fine/Restitution |

35.4 (23) |

32.5 (13) |

|

Community Service |

52.3 (34) |

10.3 (4) |

|

LSI Risk Level:** |

Low (LSI-R: 0-13; LSI-SV: 0-2) |

47.7 (31) |

34.2 (13) |

Moderate (LSI-R: 14-33; LSI-SV: 3-5) |

36.9 (24) |

55.3 (21) |

|

High (LSI-R: 34+; LSI-SV: 6-8) |

15.4 (10) |

10.5 (4) |

|

Notes. *Categories are not mutually exclusive. Also, sentencing information was incomplete. Although valid percentages are presented, missing information ranges from 1 case (community service) to 13 cases (probation).

**For risk level of the CJP offenders, LSI-R scores were available for 34 offenders; the LSI-SV was used to obtain risk levels for the remaining 31 offenders. For control group offenders, risk level data is missing in two cases.

III. Examination of the Research Questions

Research questions were posed to address four broad research categories: (1) client characteristics, (2) program activities, (3) program impacts, and (4) value-added. Under the umbrella of client characteristics, specific questions pertained to the characteristics of the offender and the victims who chose to participate in the CJP, the impact the crime had on them, the risk and need factors of the offender, the needs of the victims, and the expectations of the participants.

III. a) Client Characteristics: Three methods were used to examine participant needs. First, the participants were asked to identify their needs in the pre-meeting questionnaire and the post-program interview. Second, facilitators case notes were reviewed to obtain their perspective on client needs, strategies to address these needs, and treatment recommendations. Third, for the offenders, need areas were also examined using the LSI-R.

Victim Needs. When victims were asked what needs they wanted addressed in the restorative process, victims indicated the following: obtain information (43.2%), address the offender's needs/rehabilitation (31.1%), tell the offender how the crime impacted them (23.0%), obtain an apology/have offender make reparations (20.3%), have active involvement (16.2%), determine for themselves whether the offender was remorseful/truthful (12.2%), receive financial compensation (8.1%), receive emotional support (6.8%) and feel a sense of closure (4.1%). Victims often expressed more than one need. From the post-program interviews, 91.1% felt that their needs were met through the CJP process in the following ways: 24.6% stated that they experienced healing or felt closure, 22.8% mentioned that they were able to tell their story, 15.8% stated that they “viewed offender accountability”, 14.0% highlighted the support they received during the process, 8.8% stressed the importance of being involved in deciding offender outcome and 5.3% mentioned the apology they received from the offender. Twelve victims stated that their needs were not met. When questioned about what else could have been done to meet their needs, 33.3% (n = 4) felt their needs could have been better met if facilitators had additional training and 16.7% (n = 2) felt that there should be a psychologist present throughout the process, especially during the victim-offender meeting. In addition, 25.0% of victims (n = 3) indicated that although they felt their needs were met, there should have been additional support available to them and 25.0% (n = 3) felt scheduling delays hindered the process.

File reviews, including reviews of facilitator case notes and other case documentation, were possible for only 88 of the 112 victims. Furthermore, in many cases some information was not available. Unfortunately, the CJP did not have a standardized case-note-recording system and notes were limited if a victim did not participate fully in the CJP. The file reviews indicated that treatment was recommended to victims in 21.6% of cases. In the 19 cases where treatment was recommended, it was primarily the victims themselves who identified a need for treatment (52.6%, n = 10), followed by a CJP staff recommendation (21.1% of cases; n = 4) or an “other person” (26.3%, n = 5). Psychological counselling was the most common type of treatment recommended to victims. Reviews indicated that 11.6% of victims actually attended a treatment program. When questioned about the impact of the crime, victims reported the following: 27.5% reported physical injury, 54.5% had psychological upset but required no professional attention, and 46.6% suffered direct financial loss.

Offender Needs. Offenders were also asked what needs they wanted addressed. Offenders wanted the opportunity to do the following: apologize (24.4%), provide an explanation (24.4%), reduce their sentence (24.4%), attempt to repair the harm caused (19.5%), rehabilitate (19.5%), be made aware of the impact the crime had on the victim (9.8%) and resolve conflicting facts with the victim (7.3%). Of the 34 offenders who identified a variety of needs, 88.2% felt that their needs were met through the CJP process. Offenders indicated that their needs were met by (a) the support they received (41.4%), (b) being given the opportunity to apologize (20.7%) and (c) the opportunity to explain and answer victims' questions (13.8%). Six offenders felt that their needs were not met, and when questioned as to what else could have been done to meet their needs, 50.0% (n = 3) of offenders cited a more lenient sentence and in cases where the offender and victim did not meet, one offender felt that meeting the victim would have better addressed his or her needs.

File reviews were conducted on all 65 offenders. The file reviews indicated that treatment was recommended to offenders in 69.2% of cases. In the 45 cases where treatment was recommended, it was primarily the CJP staff that recommended treatment (57.8%, n = 26), followed by a recommendation by the offenders themselves (26.7% of cases, n = 12) or from an “other” person (24.4%, n = 11). The type of treatment that was recommended, as well as whether a treatment program was attended, are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. CJP Offender Identified Treatment Areas (n = 65)

Treatment |

% of all CJP offenders where treatment was recommended |

% of recommended who attended |

|---|---|---|

Alcohol |

26.2 (17) |

58.8 (10) |

Drugs |

20.0 (13) |

53.8 (7) |

Alcohol and Drugs |

12.3 (8) |

62.5 (5) |

Academic |

12.3 (8) |

50.0 (4) |

Vocational |

4.6 (3) |

33.3 (1) |

Financial |

4.6 (3) |

33.3 (1) |

Life Skills |

3.1 (2) |

50.0 (1) |

Psychological Counselling |

43.1 (28) |

78.6 (22) |

Overall |

69.2 (45) |

75.6 (34) |

Note. Categories are not mutually exclusive.

For offenders, a third method of examining needs was through a review of the LSI-R subscales. Each LSI-R subscale was identified as a risk/need factor if 50% or more of the items within a subscale were scored as present. Results showed that leisure1 was the most prevalent risk/need factor (67.6%, n = 23), followed by financial (47.1%, n = 16), family/marital (35.3%, n = 12), alcohol/drug problems (29.4%, n = 10), and education/employment (26.5%, n = 9). Because the LSI-SV scores only one item per need factor, the LSI-SV items were not added to this analysis.

When questioned about the impact of the crime, 8.0% of offenders required medical attention for injuries and 97.3% reported psychological upset but did not seek professional assistance. The high rate of psychological upset reported by offenders (42.8% higher than victims) is interesting and may be directly related to the remorsefulness shown by the offenders who sought out the assistance of the CJP.

Commonalities and Differences. Facilitators were asked to identify participant needs at three time periods for each CJP client. Analyses of these assessments revealed interesting results. First, facilitators identified significantly more needs for the victims (M = 3.60, SD = 0.91) than for the offenders (M = 2.50, SD = 1.61, t (69) = 3.52, p < .01). In particular, more victims (57.1%) than offenders (33.3%) were viewed as having the need for a victim-offender meeting ( c 2 (1, N = 71) = 4.06, p < .05). Furthermore, more victims (62.9%) than offenders (16.2%) were identified as having the need to explain the impact that the crime had on them ( c 2 (1, N = 72) = 16.4, p < .01); and more victims (82.9%) than offenders (24.3%) were identified as having the need to be involved in the court process ( c 2 (1, N = 72) = 24.7, p < .01).

Table 5. Clients' Needs as Identified by CJP Facilitators and by Participants (%, n)

Need |

Offender |

Victim |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Facilitator Identified |

Offender Identified |

Facilitator Identified |

Victim Identified |

|

|

n = 37 |

n = 41 |

n = 35 |

n = 74 |

Apology |

51.4 (19) |

24.4 (10) |

48.6 (17) |

20.3 (15)* |

To tell their story, impact, explain |

16.2 (6) |

24.4 (10) |

62.9 (22) |

23.0 (17) |

Hear other side / Obtain information |

40.5 (15) |

17.1 (7)** |

60.0 (21) |

43.2 (32) |

Repair harm (excludes apology) |

37.8 (14) |

19.5 (8) |

37.1 (13) |

-- * |

Offender rehabilitation |

43.2 (16) |

19.5 (8) |

11.4 (4) |

31.1 (23) |

Active involvement in court process |

24.3 (9) |

0.0 (0) |

82.9 (29) |

16.2 (12) |

Influence Sentence |

8.1 (3) |

24.4 (10) |

20.0 (7) |

0.0 (0) |

Notes. *For participant responses, often “apology” and repairing the harm were combined.

**For offenders, “hear other side” meant hearing the impact their behaviour had on the victim(s) or obtaining information in order to resolve conflicting accounts.

Perspectives on “offender rehabilitation” were explored. For an offender, this meant receiving treatment or “help”, and for a victim, it meant having the need to ensure that the offender received treatment so victimization of others would be prevented. First, facilitator perspectives were examined by reviewing the assessments. Specifically, facilitators were asked to report on their perceptions of the participants' views on the need for offender rehabilitation; according to facilitators, offenders reported this need (reported for 43.2% of offenders) significantly more often than victims (11.4%, c 2 (1, N = 72) = 9.08, p < .05). Next, the responses from the victims and offenders themselves were examined. When asked, 19.5% of offenders identified a need for rehabilitation and 31.1% of victims felt a need to have the offenders' rehabilitation needs addressed. This suggests that facilitators perceive victims as needing to see offenders rehabilitated less than the victims reported to researchers, whereas the opposite was true in the case of offenders.

Facilitators' views of offenders' and victims' needs were slightly different from those that were identified by the participants themselves (see Table 5). This difference could be attributable to a number of factors. First, facilitators' ratings and participants' ratings were obtained at different times during the process. Typically, Assessment 1 was completed after both offender and victim had begun participating in the program (although at this point facilitators may have had several conversations to identify the perspective of each party and what they were hoping to accomplish in the restorative process). The participants were asked to identify their needs in both the pre-meeting questionnaire, and retrospectively, in the post-program interview (i.e., what were the needs that you wanted addressed…). There were no significant differences in needs reported at the pre-meeting stage and at the post-program stage. Second, it is possible that the needs as identified by the facilitator were in fact different from those identified by the participants because the participants may not have felt comfortable at the beginning of the program to fully disclose their needs or reasons for participating.

Lastly, it is important to note that the results of participant needs closely overlapped with the participants' motivations for partaking in the program, which are presented next.

Participation Motivations. Participants were asked to specify what they would like to accomplish by participating in the CJP. Although there was some overlap between their reasons to participate and potential accomplishments, they are presented separately. Results indicate that victims and offenders wanted to accomplish different things and had different expectations. When asked, 33.3% of victims wanted to learn about the circumstances surrounding the offence and receive answers to questions, 26.7% of victims wanted to meet the offenders in an attempt to understand them and their actions or reasons for committing the crime, and 20.0% wanted to explain to the offenders the impact of the crime on them. Seventeen percent (16.7%) of victims wanted to obtain an apology and view remorse from the offender, and 16.7% wanted to participate in order to attempt to prevent recidivism (prevent others from being victimized) and ensure that the offender received treatment. Offenders wanted to accomplish the following: apologize to the victim (36.4%), provide restitution/attempt to repair the harm caused/reach an agreement (27.3%), feel a sense of closure (27.3%), provide an explanation to the victim (22.7%), hear the victim's experience (13.6%), and get to know the victim/become acquaintances (13.6%).

Reasons for participating were also examined, using the assessments that were completed by the facilitators. In many cases, more than one reason was recorded, so there is overlap in the motivations presented. For 81.6% of offenders, facilitators felt that the offender was motivated by personal responsibility/accountability, and by a need to repair the harm they had caused (RJ-type motivations). For 22 of the 40 offenders (55.0%), one of the motivations recorded by the facilitators was that the offender was participating to influence their sentence (more specifically, to obtain a more lenient sentence). In 7 cases (17.5%), this was the only motivation recorded. According to the facilitator's notes, 97.1% of victims were motivated by RJ-type reasons (wanting to communicate, etc.).

Victim Fear Levels. Victims were asked about their feelings of safety and levels of fear in the pre-measure. Of the 37 victims who responded, 70.3% stated that the crime had affected their feelings of personal safety. When asked to rate their current level of fear on a scale of one to ten (1 = not afraid at all to 10 = extremely afraid), the majority placed their fear level at five (M = 5.26, SD = 3.49).

Offender Accountability. At each assessment stage, facilitators were asked to evaluate the offender's degree of accountability (1 = not accountable, 2 = somewhat accountable, 3 = completely accountable). Pre-program assessments were completed on 40 offenders, and facilitators rated 52.5% of offenders as completely accountable (M = 2.54, SD = 0.51, n = 21). In order to better understand the concept of accountability and how facilitators evaluated it, a review of the reasons provided for accountability was conducted. In examining the justifications for a completely accountable rating, two main themes became evident. Forty-one percent (41.3%) of justifications noted that the offender was taking responsibility for his or her criminal behaviour and not minimizing or denying his or her actions. Thirty percent of explanations indicated the offender was experiencing emotions such as guilt, remorse, sorrow, or empathy for the victim. In cases where offenders were deemed somewhat accountable by the facilitator, the lower rating was related to aspects of denial, minimization, or justification for the offence (68.8%).

Offender Remorse. Facilitators rated the offender's level of remorse (genuinely remorseful, somewhat remorseful, not remorseful). As indicated earlier, no offenders were rated as not remorseful. At the pre-program stage, 85.7% of offenders were rated as genuinely remorseful, and 14.3% were rated as somewhat remorseful. For the genuinely remorseful rating justifications, 29.7% of justifications were based on the offender's willingness to do whatever the victim requested. In 16.2% of cases, evidence was based on the fact that the offender was making behavioural, attitudinal or life changes. These same emotions were justification for the offender demonstrating accountability in 30.4% of cases. The most frequent indicator of remorse, in facilitator's minds, was the offender demonstrating feelings of guilt and shame (35.1%). This review of rating justifications indicates that the concepts of accountability and remorsefulness are intertwined.

It is important to note that despite the facilitators' description of offenders as genuinely remorseful, in many cases, caveats were added. In 24.3% of cases where a rating of genuinely remorseful was given, there was a qualification (most commonly, the word “but”) provided in the justification/explanation. Many of these “buts” were linked to suggestions that the offender was employing various neutralization strategies, minimizations, or excuses for their behaviour. For example, “the offender is genuinely remorseful but is not fully aware of the range of the impact of the crime”, “.. feels badly … never intended to hurt anyone… but he was drunk”, and “yes, is genuinely remorseful but still feels the victim provoked him”.

III. b) Program Activity: Questions about program activity examined the process, how it worked, and the role of the mediator in the CJP process.

Almost half (44.3%) of the cases were referred to the CJP from Judicial Pre-Trials (JPT). The rest of the cases were referred to the CJP by the defence lawyer (27.9%), the Crown (18.0%), the judge (6.6%), the victim (1.6%), or another person (1.6%). A review of case notes showed that the number of face-to-face contacts between facilitators and offenders ranged from one to 25, with an average of 7 (SD = 4.1). Face-to-face contacts between facilitators and victims ranged from zero to eight, with an average of 3 (SD = 1.8). In cases where the victim and offender did not meet, but information was provided to the victims, victim updates (by phone) ranged in number from one to 17, with an average of 4 (SD = 3.6). Contact with the CJP continued post-sentence in 52.9% of cases. Post-sentence face-to-face facilitator-client meetings occurred with 26.5% of participants, and telephone contact occurred in 39.7% of cases (in many cases this was to monitor the agreement conditions). The average length of program participation, from acceptance date to last contact date, was 224 days (7.5 months, SD = 207.6).

Pre-Meeting . Prior to a victim-offender meeting, each participating respondent was asked about their feelings towards meeting the other party. Of the 55 victims who participated in a victim-offender meeting, 28 completed the pre-meeting questionnaire. Of these, 78.6% reported that they were looking forward to meeting the offender. Fourteen percent of victims (14.3%) felt reluctance, but none reported being “very worried”. Of the 20 offenders who completed the questionnaire, 95.0% reported that they were looking forward to meeting the victim. Five percent indicated that they were “very worried”. Despite looking forward to the meeting, 52.4% of offenders and 33.3% of victims reported having reservations about meeting the other party face-to-face.

Victim-Offender Meetings. Not all cases were appropriate for a victim-offender meeting. The CJP facilitators felt a victim-offender meeting, or circle, would be beneficial in 72.3% (n = 47) of all cases, and a meeting actually occurred in 58.5% (n = 38) of all cases. Meetings lasted from less than an hour to almost six hours and occurred prior to sentencing in 90.9% of cases. The remaining victim-offender meetings occurred post-sentence. In some cases, victims preferred to wait until after sentencing to meet the offender because they did not want to influence the sentence. The meetings or circles varied in size, ranging from three people (the victim, the offender and the CJP caseworker) to 14 people. Participants were encouraged to bring a support person to the meetings, which included spouses (offenders: 6.8%, victims: 10.8%), friends (offenders: 3.4%, victims: 5.4%), relatives/other family (offenders: 37.9%, victims: 8.2%), and treatment providers (offenders: 3.4%). Despite being encouraged to bring outside support, 37.9% of offenders and 16.2% of victims preferred to have their CJP caseworker provide support. Seven percent (6.9%) of offenders and 14.9% of victims indicated that there was no one to bring as support, and they did not view their CJP caseworker as a support person.

The majority of offenders (71.4%) and victims (58.7%) felt the atmosphere of the meetings was “friendly” and 96.6% of offenders and 91.4% of victims felt that they were treated fairly during the course of the meetings. In cases where a resolution plan or reparation agreement was developed (53.8%), all offenders and 91.4% of the victims felt that the agreement was fair. A review of facilitators' case notes found that an apology was given in 86.8% of cases, although it is possible that an apology was not always recorded (the Project Coordinator reported that an apology was provided in every case). During the post-program interview, 93.3% of victims indicated that they thought it was helpful to meet the offender(s) and 86.2% of offenders felt that it was helpful to meet the victim.

Reparation Agreements. Although reparation plans (also referred to as resolution plans) were typically developed in the victim-offender meeting, plans could still be developed through shuttle mediation by the facilitators. In 53.8% of cases a reparation plan was developed and agreed upon by all participants. Reparation plans (n = 35) included activities such as performing community service (50.0%), providing restitution (39.2%), attending/continuing treatment (38.8%), attending school (22.0%), and maintaining employment (14.0%). Although the Crown was not present during the development of the reparation plan, the Crown supported the reparation plan in 85.4% of these cases. At the time of sentencing, the court generally endorsed the reparation agreement in 78.9% of cases where a plan was submitted. However, modifications were made in 68.4% of these cases. These modifications were to the sentence type (50.0%), sentencing conditions (46.4%), prohibitions (25.0%), community service orders (17.9%), restitution (3.6%) and treatment plans (28.6%).

Information on successful completion of resolution agreements was limited. Analyses were conducted to determine whether the occurrence of a victim-offender meeting affected the likelihood of successfully completing a resolution agreement. CJP offenders who did attend a victim-offender meeting (57.1%, n = 12) were slightly more likely to fulfill the resolution agreement than offenders who did not attend a meeting (42.9%, n = 9). However, the differences were not statistically significant.

Process and Participant Reflections. Participants were asked a number of process-related questions. The majority (80.5%) of offenders and 93.3% of victims felt that they had been given enough information about the CJP before agreeing to participate. When asked if participating in the CJP was easier or harder than expected, 41.3% of victims and 51.2% of offenders found it easier, 26.7% of victims and 24.4% of offenders indicated that it was about what they had expected, and 24.0% of victims and 19.5% of offenders found it harder. Eight percent (8.0%) of victims and 4.9% of offenders said they did not know what to expect. The frequency of the meetings with project staff created problems for 13.3% of victims and 7.3% of offenders.

Restorative justice programs promote an inclusive approach to resolution. Accordingly, participants were questioned as to whether they felt that their opinions were adequately considered. For participants who completed the post-program interview, over eighty percent of victims (88.0%) and offenders (82.9%) felt that their opinions were adequately considered.

Strengths and Difficulties. Participants were asked about the strengths and difficulties of the program. Responses from offenders and victims were similar and therefore, are presented together in Table 6. Participants reported that the greatest strength of the program was “getting [everyone] together” (victims: 47.3%, offenders 43.9%); however, interestingly, “meeting the other person” (victim/offender) was identified as the most difficult aspect to the process (victims: 41.3%, offenders: 40.0%).

In the case completion interview, the CJP caseworkers were asked about any notable difficulties with the case. The most commonly cited difficulties were lack of participation/cooperation to bring together all individuals involved in the case (42.2%), personal issues of participants such as mental health and substance abuse (31.1%), and difficulties due to the court process delays and time since the incident (17.8%). In 13.3% of cases, no difficulties were noted.

Table 6. Participant-identified Strengths and Difficulties of the CJP Process (%, n)

Aspect |

CJP Offenders |

CJP Victims |

|---|---|---|

Greatest Strength (%) |

n = 41 |

n = 74 |

Victim-Offender Meeting (“Getting together”) |

43.9 (18) |

47.3 (35) |

Active involvement in the process |

34.1 (14) |

28.4 (21) |

Coming to terms with the crime/feelings of closure |

26.8 (11) |

23.0 (17) |