What We Heard and Learned Report: CSIS Act Consultations

Consultations on Amendments to the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act

Table of Contents

Executive summary

In November 2023, the Government of Canada launched public consultations on possible amendments to the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act (the CSIS Act) that would better equip CSIS to carry out its mandate to investigate, advise the Government of Canada, and take measures to reduce threats to the security of Canada and all Canadians. The consultations included an online survey available to the public and direct engagement with provincial and territorial governments; Indigenous governments; the private sector; academia; legal, privacy and transparency experts; community and religious representative organizations; and other civil society stakeholder and partner groups. The consultation process was a valued experience for the Government, and provided an opportunity to reach out to and learn from many civically-engaged members of Canadian society.

Participating Canadians indicated a general understanding that advancements in technology and evolving threats have created a need for changes to the CSIS Act, and favoured amendments. Respondents held a generally positive view toward the amendments under consideration, though there was variability between the categories in the degree of support.

While support was strong, not all participants favoured the proposals. A minority of respondents expressed concerns specific to privacy and the need for strong oversight and accountability, with contributions also reflecting the importance of building trust in CSIS and encouraged continued transparency.

Taken as a whole, most participants acknowledged that the proposed amendments could better equip CSIS and the Government to respond to national security threats such as foreign interference.

Introduction

As an advanced economy and open democracy, Canada is targeted by foreign states, or those acting on their behalf, who seek to advance their strategic objectives. While foreign states may advance their interests by legitimate and transparent means, some also act in ways that threaten or intimidate people in Canada, their families elsewhere, or are covert and deceptive, and harmful to Canada’s national interests. Advancements in technology have only enabled and accelerated these threats, especially in the online space.

On November 24, 2023, in response to this evolving threat landscape, the Minister of Public Safety, Democratic Institutions and Intergovernmental Affairs, the Honourable Dominic LeBlanc, announced the launch of public consultations on foreign interference (FI) that propose amendments to the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act (the CSIS Act). Amendments to the CSIS Act would better equip CSIS to carry out its mandate to investigate, advise the Government of Canada, and take measures to reduce threats to the security of Canada.

In keeping with its commitments to transparency and public engagement, the Government chose to seek out a broad set of public and partner perspectives through two methods of engagement: an online survey and roundtable discussions.

The online consultation survey was available from November 24, 2023, to February 2, 2024, a period during which the Government solicited and received broad and diverse input from many corners of Canadian society. The process was monitored for any sign of irregular submissions, including from outside of Canada and potential bots. No significant irregularities were identified, indicating that the results represent the views of Canadians. While a plurality of the 360 online respondents identified as members of the public, others identified as members of community groups, academia, industry, religious organizations, or the federal government. Respondents were directed to a consultation paper that outlined in detail the issues upon which they would be surveyed, after which they could respond to 13 substantive questions addressing issues from five categories:

- Whether to enable CSIS to disclose information to those outside the Government of Canada for the purpose of increasing awareness and resiliency against FI;

- Whether to implement new judicial authorization authorities tailored to the level of intrusiveness of the techniques;

- Whether to close the gap, created by technological evolution, and regain the ability for CSIS to collect, from within Canada, foreign intelligence about foreign states and foreign individuals in Canada;

- Whether to amend the CSIS Act to enhance CSIS’ capacity to capitalize on data analytics to investigate threats in a modern era; and,

- Whether to introduce a requirement to review the CSIS Act on a regular basis so that CSIS may keep pace with evolving threats.

The Government also engaged a broad array of stakeholders and partners in roundtable discussions, including provinces and territories; Indigenous governments; the private sector; academia; legal, privacy and transparency experts; community and religious representative organizations; and other civil society groups. Participants of these discussions included representatives from all provinces and territories; Inuit, Métis, and First Nations associations and rights holders; industry leaders and organizations in Canada’s business and technology sectors; Canadian university and faculty leadership; and organizations representing Canadians of Chinese, Ukrainian, Russian, Iranian, Sikh, Hindi heritage, as well as other civil society organizations. This was a significant opportunity to build public awareness on the issues facing all Canadians and its institutions with a view to bolster our collective resilience. Roundtables were also an opportunity to explore community perspectives and concerns, safeguards, and transparency. In total, 55 separate organizations and governments were consulted, as well as 10 individual academics and experts not associated with the organizations.

Taken together, welcomed contributions from the online survey, direct engagement, and other sources will inform the Government’s discussions and planning toward possible amendments to the CSIS Act that will strike the right balance between protecting national security and respecting Canadians' privacy.

Results

Direct stakeholder and partner engagement

Among stakeholders and partners who participated in roundtables, where the Government was well positioned to explain CSIS’ challenges and respond directly to questions, there was general agreement regarding the need for changes to the CSIS Act to rectify areas where it has become outdated. Many expressed support for efforts toward legislative change and recognized the need to address the growing threat of FI in Canada, as well as surprise at times at the limitations CSIS faces. Several were appreciative of the opportunity for their input on the amendments to be heard. Calls for continued public engagement and transparency in the spirit of rebuilding trust were oft repeated, especially in light of the difficult relationships that some communities in Canada have historically had with the Government of Canada.

Discussions with a diverse set of stakeholders and partners brought valued insights regarding the potential amendments. The issue that was most commonly of interest was information sharing. Some of the more technical proposals, such as changes to the dataset regime, were less frequently discussed during the roundtables.

For the most part, comments about the proposed amendments during the roundtables were positive, and stressed the importance of effective implementation, safeguarding information, and ensuring respect for privacy. Some others expressed concern over a lack of ambition or offensive strategies in the amendments.

Views from Indigenous partners were overall positive, with a few raising concerns. While Métis, Inuit and some First Nations representatives generally viewed the proposed amendments positively, one First Nations partner expressed concern that their ability for self-governance could be impacted if the legislative amendments were introduced, especially regarding key business and investment relationships. Other First Nations representatives reminded the Government of their concerns about investigations against Indigenous peoples and that Indigenous peoples in Canada may hold a differing perspective on, or interpretation of, what Canada considers to be FI.

While many were supportive of the proposals and understood the necessity of the amendments, some civil society groups expressed concerns that members of diaspora communities, especially those disproportionately affected by FI, could be inadvertently impacted by new measures. They also highlighted that potential prejudice or bias against certain communities must be considered and this risk be mitigated in any proposed legislative amendments.

Online responses

360 persons submitted responses to the online survey between November 24, 2023 and February 2, 2024. Survey respondents were first asked to identify themselves as belonging to one of the eight categories outlined in the figure below. A plurality (46%) of respondents identified themselves as members of the public. See Figure 1 for the complete results.

Figure 1: Distribution of respondents to online public survey, self-identifying as members of:

Image Description

A bar graph depicting the online respondents by category. 46.1% of respondents identified as members of the public, 16.1% as members of the business community, 14.2% as members of the Canadian government, 9.7% as academics, 1.9% as belonging to a non-governmental organization, 1.9% belonging to a community representative organization, 0.8% as a religious organization, while the remaining self-identified in the “other” category.

Both qualitative and quantitative analyses of the responses indicate that respondents were generally supportive of affording CSIS the tools it requires to investigate and respond to modern threats such as FI. Responses frequently included statements about the need for Canada to be stronger in the face of national security threats like FI.

Further, respondents held a generally positive view toward the need for amendments across each of the five categories, though there was variability between the categories in the degree of support. They most strongly favoured the proposal for periodic review of the CSIS Act, as well as amendments related to information sharing and section 16 of the Act.

Some were critical of the amendments, for instance indicating that they would prefer to see a broader scope for change. There was also a subset of respondents whose answers across the survey indicated general mistrust of or discontent toward CSIS, the security and intelligence community, the Government as a whole, or specific politicians and parties. These sentiments often accompanied negative responses to the full set of questions, and sometimes included broader comments regarding CSIS or Government capabilities, intentions, activities, policies, or corruption.

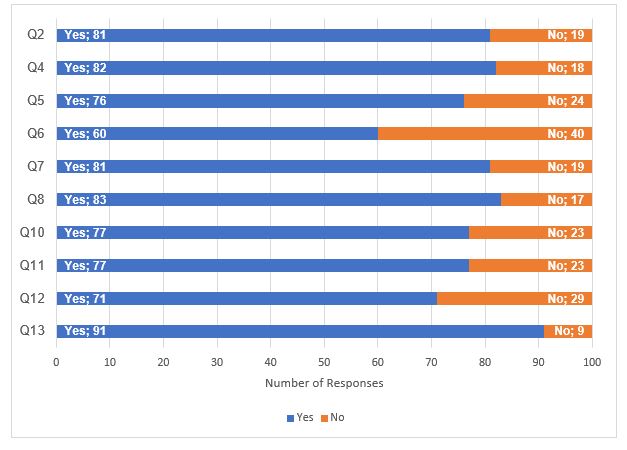

Figure 2: Distribution of responses across online public survey questions

Image Description

A stacked bar chart depicting the number of yes and no responses across the online public survey questions.

Questions that do not appear in the figure above (i.e. Q1, Q3, Q9, and Q14) were excluded because they are not yes/no questions. See Annex A for the list of questions.

| Responses to Question (by number) | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 81 | 82 | 76 | 60 | 81 | 83 | 77 | 77 | 71 | 91 |

| No | 19 | 18 | 24 | 40 | 19 | 17 | 23 | 23 | 29 | 9 |

In depth review of the responses to several of the questions in the online survey also made clear that, had additional context or clarification been provided by CSIS, there could have been differing and potentially higher levels of support. For example, as shown above, support in response to Question 6 (related to new judicial authorization for a single collection activity) lagged behind many of the other questions. In reviewing written responses, it is clear that many respondents were either unaware of existing safeguards in the warrant approval process or that these measures would be exercised with a warrant from the Federal Court. The online survey was an opportunity for the Government to learn and make adjustments for clarity when meeting with stakeholders and partners, affording participants a better understanding of the proposals and existing safeguards.

Other

Inputs regarding the issues under consultations came from other avenues as well. The Government received commentary from prominent national security pundits, universities, the Intelligence Commissioner, and others who submitted their views in writing. Some recognized the need for changes to the CSIS Act, while expressing the position that the proposals could have been more ambitious or bold. Specifically, the information sharing and periodic review proposals were described by most as clearly necessary, while the changes to section 16 foreign intelligence collection should have considered an overhaul rather than adjustments. Further, some wanted to see reconsideration of the definition of threats to the security of Canada under section 2 of the CSIS Act, which also came up in some roundtable discussions. Others shared unequivocal support for the range of proposals under consideration, with a view to strengthening the Government of Canada’s responsiveness to threats.

While written submissions were overall supportive of proposals to update the CSIS Act, some limited negative feedback was also received. Specifically, two written submissions took issue with most of the proposals. More detail is provided below on the character of that feedback, which aligns with a small subset of the input received through the online consultations.

Results by category of amendment

1. Whether to enable CSIS to disclose information to those outside the Government of Canada for the purpose of increasing awareness and resiliency against FI.

There was widespread agreement that it would be sensible for CSIS’ mandate to include sharing information beyond the Government of Canada, and that this would help mitigate a broad range of threats and build awareness and resilience for those at risk. There was some emphasis on sharing information with provincial, territorial, Indigenous, and municipal governments, those carrying out government functions, as well as local law enforcement and universities. For instance, this could include regular security briefings for provincial and territorial politicians. Responses also noted that this could create a collaborative security strategy that benefits CSIS, while building more trust.

Discussion and input focused on issues related to implementation. Some specified where and with whom they felt limits should exist on sharing and raised important considerations around privacy and Charter protections; additional resources; declassification; security clearances for those receiving information; information sharing arrangements and procedures; oversight and accountability; the imperative not to share information in ways that would sway public opinion; options for onward sharing, risks of sharing with the wrong people, and other unintended consequences. Several also raised the issue of infrastructure to receive secure information, as well as questions about the ability to take action based on sensitive information from CSIS.

During direct stakeholder and partner engagements, there was strong interest in this proposal. Some wondered whether this would allow CSIS to alert activists or other community members to the threats they face. There were also questions about thresholds for sharing, as well as clarification regarding the process for determining how and when information would be shared. In the context of combatting electoral interference, there was endorsement of this amendment with an emphasis on enabling information to reach those responsible for electoral management in a timely and apolitical manner.

Provinces and territories considered information sharing a major priority, especially in the context of protecting critical infrastructure from threats. Discussion usually centered on the mechanics of implementation, including clearances and infrastructure to receive the information, as well as how they could use classified information given its sensitivity.

The Government also heard directly from Canadian business interests that echoed the need for comprehensive changes to the Act, with a special focus on information sharing, highlighting the ways intelligence could help protect Canada’s economic security or Canadian financial markets while also benefitting CSIS and the Government by building trust. It was proposed that the Government establish a formal intelligence exchange medium that would ensure the secure and efficient sharing of information with external partners.

A Canadian University noted in a written submission that on campuses, where universities may be ill-equipped to respond to sophisticated threats, more information sharing would establish collaborative relationships that could respond to FI, espionage, and research security threats, as well as violent extremism. At present, the limited and unclassified information that CSIS is able to share with schools can often be dismissed on account of a lack of concrete information. Universities lack the resources to manage the evolving threat landscape and therefore require more support by way of detailed information sharing in order to integrate security consideration into the institutions’ culture and decision-making while building trust and transparency. This includes trends and best practices to mitigate threats, and specific timely threat information.

A written submission opposed the information sharing amendment, based on concerns of the possibility for prejudice or increased surveillance toward certain communities, privacy protection, as well as mistrust about governments, the private sector, and academic institutions inappropriately sharing the information they receive. Another submission shared these views while also raising that more evidence was needed to support the proposal, that the Government should explore non-legislative approaches to enable greater public sharing, and that measures should be included to ensure accuracy and recourse for entities to defend themselves if they feel that intelligence has been wrongly shared against them.

2. Whether to implement new judicial authorization authorities tailored to the level of intrusiveness of the techniques.

Views varied depending on the specific proposal, as this category covers several differing authorizations. However, support consistently outweighed opposition based commonly on the investigative expediency, parity with law enforcement, and national security arguments, as well as the imperative for CSIS to have a variety of tools proportional to the threats. Support was especially strong for CSIS being able to obtain a preservation order and delegation of ministerial authorization in exigent circumstances, with results also strongly supporting a production order authority. Some noted the need for clear guidelines and reporting, while others expressed concern that CSIS could not already obtain these judicial authorizations. Respondents fairly consistently mentioned the need to ensure privacy and Charter protections, while some others noted the need for new resources to complement the proposal. In roundtable discussions, one stakeholder sought to ensure that these processes be guarded against biases.

Two related written submissions raised concerns with the judicial authorizations proposals, claiming that these warrants are not as easily challenged in open court and therefore not be subject to the same level of transparency. This submission also contended that a single-use collection authority would open access to the collection of incidental information not targeted by the warrant. Respondents cautioned that new authorities should only be exercised through applications to the Federal Court for warrants, which aligns directly with the proposed amendments.

3. Whether to close the gap, created by technological evolution, and regain the ability for CSIS to collect, from within Canada, foreign intelligence about foreign states and foreign individuals in Canada.

There was strong support for proposed amendments to section 16 of the Act, with many arguing that some of the limitations on foreign intelligence collection should be removed and some saying there is a need for a Canadian foreign intelligence agency. One written submission argued for the removal of “within Canada” from section 16, in recognition of unforeseen gaps created by the geographical restrictions in the Act.

There was discussion among academics participating in roundtables about broader changes to, or complete removal of, section 16 that would improve the collection of foreign intelligence and treat foreign intelligence collection the way CSIS treats security intelligence.

One written submission was concerned about the possibility of encroachment on the Communications Security Establishment’s (CSE) mandate, as well as the need to ensure foreign intelligence collection continues to exclude Canadians.

4. Whether to amend the CSIS Act to enhance CSIS’ capacity to capitalize on data analytics to investigate threats in a modern era.

Many respondents endorsed extending the evaluation period for datasets and others proposed several useful suggestions, including increased investment in human and technological resources, and removing the dual tracks of Canadian and foreign datasets, while reiterating the imperative of continued respect for Charter and privacy protections, as well as oversight and review mechanisms. The large majority favoured allowing the use of section 11 datasets for section 15 purposes, at times noting the importance of this proposal and others toward remaining relevant as an intelligence organization in the digital age.

With regard to sharing of datasets with domestic and foreign partners, stakeholders also indicated support. Several helpful considerations were raised, including data minimization and anonymization principles, vetting of recipients, reciprocity from partners, sharing only with trusted partners, and external review or oversight. Some argued that limitations on foreign datasets should differ from those for Canadian datasets, while others voiced their worries of misuse by foreign partners.

The Intelligence Commissioner’s input addressed a number of areas, all related to the dataset regime. These namely included the importance of maintaining oversight, protections for privacy, an extension of the evaluation period beyond 90 days, the removal of Canadian information from datasets shared with partners, and resolving interpretative differences between the English and French versions of the legislation.

A written submission strongly opposed the use of Canadian datasets for security screening based on what they viewed as prior unacceptable uses of data by CSIS. The cases cited as examples date from before the establishment of more rigorous statutes on CSIS collection and use of data through the 2019 implementation of Bill C-59. Another submission similarly argued that not enough evidence was provided to support the proposal and that the Government should allow the mandated review of Bill C-59 to evaluate the dataset regime and its effectiveness. This submission also contended that the tools are already in place to prevent the untimely loss of datasets and that ample powers exist already for CSIS to share information with partners. Any additional sharing should not be authorized in light of the difficulty controlling and safeguarding its use once shared.

5. Whether to introduce a requirement to review the CSIS Act on a regular basis so that CSIS may keep pace with evolving threats.

Responses consistently favoured incorporating periodic statutory review of the CSIS Act, though views on the frequency ranged greatly. This included a written submission that described the CSIS Act as limited and outdated. This submission expressed support for regular periodic review of, and reporting on, the Act on the basis that it would demonstrate Canada’s commitment to security without removing Parliament’s prerogative to review at any time, while addressing rapid and unforeseen advancements in technology and threats.

Input from roundtable discussions and another written submission also noted that periodic review would give the government an opportunity to consider concerns raised by review agencies or civil liberty groups, effectiveness and necessity of powers, and possible new restrictions of mandate, for example. The more common responses regarding frequency of reviews suggested they be done every two to five years, though some felt a longer period was needed to allow time to observe the impacts and outcomes of changes.

Conclusion

Overall, Canadians who participated in this consultation generally understood the need for changes to the CSIS Act, and agreed that existing gaps are problematic. Many respondents acknowledged that the proposed amendments could better equip CSIS and the Government to respond to national security threats such as FI.

While support was strong overall, some respondents expressed specific concerns regarding the importance of privacy and the need for strong oversight and accountability. Contributions also emphasized the importance of continued efforts to enhance trust in CSIS and encouraged continued efforts to increase transparency even further. The consultation process was a valued experience for the Government of Canada, and offered an opportunity to have a dialogue with Canadians about CSIS’ important mission.

Many Canadians recognize the challenge and importance of national security to Canadian society. There was a continuing desire to engage more about CSIS’ work, as well as its priorities, challenges, and mission. These takeaways will help guide the organization in remaining a modern intelligence service that can ensure the safety, security, and prosperity of Canada and all Canadians.

Thank you to all who participated in the online and direct stakeholder engagements.

Annex A – categories and questions

Q1. What is your professional background/institutional affiliation?

Whether to enable CSIS to disclose information to those outside the Government of Canada for the purpose of increasing awareness and resiliency against foreign interference.

Q2. Should CSIS be authorized to disclose information to those outside of the Government of Canada to build resiliency against threats, such as foreign interference?

Q3. In your view, what considerations should apply to the sharing of information with those outside of the Government of Canada about the threats they face? What type of limits should there be on when and with whom CSIS can share information?

Whether to implement new judicial authorization authorities tailored to the level of intrusiveness of the techniques.

Q4. Should CSIS be able to compel an entity to preserve perishable information when it intends to seek a production order or a warrant to obtain that information?

Q5. Should CSIS be able to compel production of information when it reasonably believes that the information is likely to yield information of importance that is likely to assist in the performance of its duties and functions under sections 12 or 16 of the CSIS Act?

Q6. Should CSIS be able to conduct a single collection activity, like a one time collection and examination of a USB reasonably believed to contain threat-related information, without having to demonstrate investigative necessity?

Q7. In situations where the Minister of Public Safety is unable to authorize the making of a CSIS application for judicial authorization to the Federal Court and where the matter cannot wait, should there be a mechanism to delegate this authority?

Whether to close the gap, created by technological evolution, and regain the ability for CSIS to collect, from within Canada, foreign intelligence about foreign states and foreign individuals in Canada.

Q8. Should the CSIS Act be amended so that CSIS’ ability to collect foreign intelligence at the request of ministers can keep pace with the evolution of technology, which creates digitally borderless information?

Whether to amend the CSIS Act to enhance CSIS’ capacity to capitalize on data analytics to investigate threats in a modern era.

Q9. How could CSIS increase its ability to collect and use datasets in a timely and relevant manner, while respecting protected Charter rights, in a data-driven world?

Q10. Should CSIS be able to query or exploit Canadian datasets for section 15 purposes?

Q11. Should CSIS be able to share Canadian or foreign datasets with domestic partners who have the lawful authority to collect the type of information contained in the dataset?

Q12. Should CSIS be allowed to share foreign datasets with foreign partners?

Whether to introduce a requirement to review the CSIS Act on a regular basis so that CSIS may keep pace with evolving threats.

Q13. Should legislation require that CSIS’ authorities be regularly reviewed to keep pace with technological advances and Canada’s adversaries?

Q14. Do you have any other views to share regarding the development and possible amendments to the CSIS Act?

- Date modified: