Guide on the Implementation of Evidence-Based Programs: What Do We Know So Far?

Guide on the Implementation of Evidence-Based Programs: What Do We Know So Far? PDF Version (434 KB)

Guide on the Implementation of Evidence-Based Programs: What Do We Know So Far? PDF Version (434 KB) Table of contents

- Summary

- Introduction

- 1. Program implementation study

- 2. Stages of the program implementation process

- 3. Systemic approach of factors impacting the implementation process

- 4. Key components of the implementation process

- 5. Implementation teams

- 6. Fidelity in program implementation

- 7. Findings on the implementation of crime prevention programs

- Planning Tools

- Stage 1. Checklist for activities related to the exploration and adoption stage

- Stage 2. Checklist for activities related to the preparation and installation stage

- Stage 3. Checklist for activities related to the initial implementation stage

- Stage 4. Checklist for activities related to the full implementation stage

- Checklist for activities related to sustainability

- Case Studies

- 1. Blueprints for Violence Prevention Initiative: Main challenges in the implementation process

- 2. Obstacles of the implementation of a secondary alcohol prevention program

- 3. Implementation of a school evidence-based substance abuse prevention program: Some examples of challenges

- 4. School-based programs: What facilitates their implementation?

- 5. Blueprints for Violence Prevention Initiative: Key elements of a high-quality implementation

- 6. Program adaptations based on implementation contexts: Some findings

- 7. Facilitators and obstacles of the implementation of an evidence-based parenting program with fidelity

- 8. Program implementation in Aboriginal communities

- Appendix

- References

- End Notes

Summary

Through its National Crime Prevention Centre (NCPC), Public Safety Canada fosters the development and implementation of evidence-based crime prevention interventions in Canada. To this end, the NCPC supports the implementation and evaluation of community-based initiatives to identify what works, how it works, and what it costs.

The question of "how" has often been overshadowed in favour of the demonstration of program impacts. Yet the quality of the implementation of prevention programs is a key factor in their success. For example, an effective implementation of a promising program has a greater chance of producing positive results than a less rigorous implementation of a model program. Program results that demonstrate little effectiveness may not be caused by a lack of sound treatment and intervention, but by weaknesses in the program's implementation.

Practitioners and researchers in crime prevention increasingly face a common challenge: the successful, effective implementation of evidence-based practices. The emergence of this interest in implementation-related issues coincides with the realization that merely selecting an effective program is not enough and that, even with the development of best practice guides, various experiences in the field have shown that effective programs have not delivered the expected results. An effective program, combined with a high-quality implementation, increases the likelihood of achieving positive results among the clients served. Emphasis should be placed not only on program selection, but also on the identification of effective conditions for implementation.

Presently, the literature confirms that some aspects of implementation are generalizable, particularly with regard to the stages and key components. Whether it is a crime prevention program or a program in a related field, for example in the education or health and social services sector, implementation is based on the same general core principles. However, certain conditions in the implementation of crime prevention programs suggest that there may be certain elements, even particular challenges and facilitative strategies that are specific to this sector. The fact that these programs target a population with multiple risks, sometimes even clients with a criminal record; the identification of young people with the right profile to participate in the program and their recruitment; the use of retention strategies to maintain participation in the program; the sometimes limited involvement of families; and the dual role of certain partners are just a few instances illustrating that the implementation of prevention programs requires strategies adapted to these conditions. An approach including empirical studies specific to the implementation of crime prevention programs must be pursued in order to shed light on these questions.

This guide on the implementation of evidence-based programs outlines current knowledge on key elements, proposes implementation planning tools and provides examples from various case studies.

Introduction

Program implementation

Is defined as a specific set of activities aimed at implementing an activity or program. It is a process that involves decisions, actions and corrections in order to deliver a program through a series of activities geared toward a mission and results.

(Fixsen et al., 2005)

It is well known that the level and quality of the implementation of prevention programs affect the results obtained (Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Fixsen et al., 2005, 2009; Fixsen & Blase, 2006; Metz et al., 2007a,b,c; Mihalic et al., 2004a,b). Effective implementation increases a program's likelihood of success and leads to better results for participants. Moreover, a dynamic, committed and open context that is amenable to change will facilitate a program's integration. The formula below illustrates this rationale.

Formula for successful use of evidence-based programs

Effective program + Effective implementation + Enabling context =

Increased likelihood of positive results(Fixsen et al., 2013)

Negative or mixed results from a program's impact evaluation may be linked to a poor quality implementation and do not necessarily mean that the program is not working (Durlak & DuPre, 2008). A meta-analysis conducted by Wilson et al. (2003) of 221 school-based prevention programs targeting aggressive behaviours revealed that implementation was the second most important variable influencing the results obtained overall (Durlak & DuPre, 2008). Footnote 1 Similarly, Smith et al. (2004) indicated that even though 14 schools obtained modest effects in the implementation of anti-bullying programs, those schools that monitored the key variables related to implementation reported twice the average with regard to effects on self-reported rates of bullying and victimization compared to schools that did not monitor the implementation process (Durlak & DuPre, 2008).

One of the prerequisites of a successful implementation also lies in the clarity of the program and its operationalization. The more clearly the key components of the program are explained (e.g., dosage, activities, etc.) and the more training and technical assistance are available, the more those responsible for the program will be able to focus on the key components associated with a high-quality implementation and promote an adequate replication of the program.

Who is this document for?

This document is intended for anyone interested in the implementation of programs in the field of crime prevention or in a related field.

How to use this document?

The central objective of this document is to disseminate practical knowledge that can be used as a guide for the implementation of crime prevention programs. This guide is also a reference tool, and we encourage you to consult it periodically during your program's implementation process.

Although it is by no means exhaustive, this document covers the following topics:

- Implementation study: Demonstrates that a high-quality implementation is an important determinant in achieving results for evidence-based programs;

- Stages in the implementation process: Explains that implementation is not a single event, but rather a long-term process made up of several stages;

- Systemic approach of factors impacting the results of implementation and the key components: Illustrates the variables that impact, both positively and negatively, the implementation of evidence-based programs and the key components of a high-quality implementation;

- Implementation teams: Stresses the importance of having individuals dedicated to implementation;

- Fidelity in program implementation: Reiterates the importance of adhering to the original program while providing some examples of the types of adaptations that are possible.

This guide also includes two practical sections:

- A first section "Planning Tools" contains checklists of key activities for each of the stages of implementation; and,

- A second section "Case Studies" illustrates lessons learned following the evaluation of programs or initiatives in crime prevention or in related fields.

1. Program implementation study

Increasingly, programs are evaluated in order to measure their impact on a target group; such as their ability to reduce problematic behaviours or to strengthen protective factors. Identifying the programs that work and those that do not is done through rigorous evaluations, and registries/databases classify these programs according to various criteria of effectiveness. Footnote 2 In comparison, knowledge concerning the conditions for implementing these programs has not progressed as far. Indeed, there are still many questions: Why doesn't a model program always obtain the same results? What factors influence the implementation conditions? How can consistency in results be maintained across various replication sites?

Implementation science

To address these questions, an implementation science has been gradually developed. Implementation science can be described as the field of study from which methods and frameworks have been developed to promote the transfer and use of knowledge in order to optimize the quality and effectiveness of services (Eccles, 2006). To connect the domains of research and practice, implementation science examines gaps between research and practice as well as individual, organizational and community influences surrounding the implementation process.

The science of program implementation

Is defined as the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic adoption of research results and other evidence-based practices in current practices with a view to improving the quality (effectiveness, reliability, security, relevance, equity, efficiency) of services for the public. Implementation science is multi-sectoral and also applies to programs in the areas of health and wellness and education, as well as crime prevention.

(Adapted from Eccles et al., 2009)

Results from process evaluations are one of the main sources of knowledge about favourable conditions and challenges surrounding implementation. Examples include the manner in which a program was, or was not, successful in reaching the target group; selecting the right participants; and/or adequately delivering interventions while respecting the dosage. Data from a process evaluation is unique and provides many details about the way in which a program is implemented Footnote 3.

This attention given to implementation also helps to distinguish what pertains specifically to the program versus what pertains to the way in which the program is implemented (Metz, 2007):

- The activities and key components of the program (e.g., individual therapy, skills development, empowerment) and the program's impact results

versus - The activities and key components of the program's implementation (e.g., recruitment of qualified staff, training and supervision, recruitment of youth) and the results of the implementation process.

A promising program that is implemented effectively has a greater chance of producing positive results than a model Footnote 4 program where the implementation is constrained by multiple gaps and limitations. Additionally, a program evaluated as having neutral effects can be replicated under different conditions and can obtain positive results. Implementation conditions must be considered as a key element in whether results are achieved.

2. Stages of the program implementation process

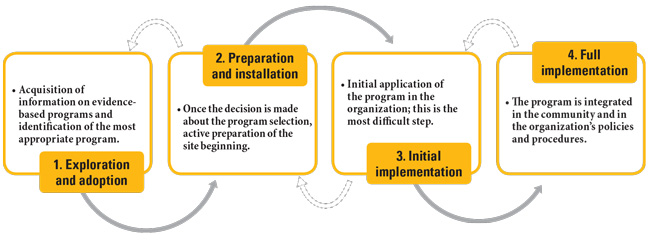

There is a consensus that program implementation is not a unique, linear event but rather a dynamic, iterative process within which multiple steps overlap and which requires the use of strategies and key components (Fixsen et al., 2005). The stages that appear to be central and generalizable within effective implementation strategies and approaches are illustrated in the figure below.

Figure 1: Stages of the program implementation process

Image Description

This chart illustrates the stage of the program implementation process which is as follows:

1. Exploration and adoption

- Acquisition of information on evidence-based programs and identification of the most appropriate program.

2. Preparation and installation

- Once the decision is made about the program selection, active preparation of the site beginning.

3. Initial implementation

- Initial application of the program in the organization; this is the most difficult step.

4. Full implementation

- The program is integrated in the community and in the organization's policies and procedures.

These stages of implementation:

- represent a dynamic, iterative process;

- are accompanied by a set of key activities carried out at different times (the "Planning Tools" section outlines these activities in the form of checklists);

- are interconnected and affected by various internal and external organizational factors; challenges addressed (or not addressed) in one stage will impact the entire process

- for example, high staff turnover could require an organization to go back to a previous stage of implementation;

- are associated with structural and procedural changes: programs are not plug and play; a number of changes will take place in the organization and various forces will take place, including forces of resistance;

- are spread out over a period of two to four years.

Following full implementation of the program, Footnote 5 there are two other stages that are not included in the figure above as they represent more of a continuation or adaptation of an already existing program.

Sustainability/Continuity: Even if this stage appears to be a logical continuation once a program ends, sustainability must be analyzed in the initial development phases. Program continuity will be achieved, for example, through secure funding, continued commitment from partners and ongoing employee training—in short, by maintaining the initial resources that were necessary during the launch of the program. In other words, it is about finding ways through which program effectiveness can be maintained over the long term considering the changing conditions compared to the initial implementation.

Innovation: Once the program has been implemented by closely maintaining fidelity to the original program, an organization might decide to adapt certain aspects of the program. This step includes discussions with experts and program developers to ensure that the key components of the program will not be affected by these changes. In other words, it is about making good use of program evaluation(s) and trying to identify the conditions in which the program obtains the best results.

"Planning Tools" Section

Each stage of implementation requires a series of activities. Detailed checklists have been created to help you become familiar with these activities, determine the strengths and weaknesses of your organization, and develop an implementation plan specific to your needs and resources.

- Overview of key activities based on the stages of the implementation process

- Stage 1 – Activities related to the exploration and adoption stage

- Stage 2 – Activities related to the preparation and installation stage

- Stage 3 – Activities related to the initial implementation stage

- Stage 4 – Activities related to the full implementation stage

- Activities related to the sustainability stage

3. Systemic approach of factors impacting the implementation process

Depending on contexts and organizations involved, a number of factors will positively or negatively influence the implementation process. Footnote 6 Table 1 illustrates some of the factors most often cited in the literature. In general, meta-analyses focusing on the program implementation process have shown the necessity to adopt a multi-level approach in order to take into consideration all of the factors related to the program characteristics, practitioners and communities, as well as those related to organizational capacity and support for prevention (training and technical assistance) (Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Gray et al., 2012; Wandersman et al., 2008).

Factors influencing the implementation process

There are many factors that influence the implementation process; these can be described as elements which, through their presence/absence and their quality, will positively or negatively impact the implementation process (facilitators or obstacles). These factors refer to key components as well as external factors. Also, mirror effect has been observed and as such, some implementation facilitators become obstacles if they are absent or missing.

(Simoneau et al., 2012)

Table 1: Main factors influencing the implementation process

I. Main factors related to the social context

- Political environment

- Commitment to prevention

- Empowerment / readiness of communities

II. Main factors related to the organizations

- Organizational capacity

- Level of site readiness

- Organizational stability, shared decision making and common vision

- Presence of champion(s)

- Quality of management support

- Coordination position

- Resources dedicated to evidence-based programs

- Staff selection*

- Coaching*

- Linkages with other external networks and partners*

- Engagement and commitment from management*

- Leadership*

- Evaluation and use of performance measures and information management system*

III. Main factors related to the practitioners

- Attitudes toward and perceptions of the program

- Level of confidence

- Skills and qualifications*

IV. Main factors related to the program

- Integration of the program and its compatibility

- Training and technical assistance*

- High staff turnover

* Factors with an asterisk (*) indicate that they are key components of implementation and will be discussed further in the next section.

As illustrated, there are many factors that influence the implementation process, and their interconnectedness is complex so it is difficult to make generalizations and predictions. Apart from the positive influence of the key components whose effects have been measured in scientific studies, it remains difficult to draw conclusions about other factors or to measure their interactions and under which conditions. In one study on the implementation of a mental health program in schools, Kam et al. (2003) observed a significant effect between management's support for the program and the fidelity of the implementation by teachers. When these two factors were high, significant positive results were noted among the students; however, when management's support was weak, negative changes were seen among the students.

I. Main factors related to the social context

Factors related to social context focus on links within the community, resources, leadership, participation, sense of belonging, and willingness to intervene in community-based problems.Various concepts have been developed by researchers to refer to these factors Footnote 7: community capacity, community readiness for prevention, community competency, and community empowerment. In any case, from a practical point of view, it is important to keep in mind that various factors related to the context in which the program is implemented will have an impact on the program implementation process (e.g., social, cultural, political and economic factors).

II. Main factors related to the organizations

Organizational capacity

While there are many ways to present factors related to organizations, in general they are referred to as organizational capacity. Capacity can be defined as the necessary skills, motivation, knowledge and attitudes required at the individual, organizational and community levels to implement a program (Wandersman et al., 2006 in Flaspohler et al., 2008). Developing all of the initial capacities required to support a good-quality implementation can take six to nine months (Elliott & Mihalic, 2003). Appendix 1 outlines some of the key attributes associated with the concept of capacity.

Also it is important to distinguish between the organization's general operations and the capacity required to implement a specific program. In fact, factors associated with organizational capacity can be classified according to the following three sub-categories (Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Gray et al., 2012):

- General organizational factors: work environment, standards for change, shared vision and integration mechanisms for the new program;

- Organizational practices: shared decision making, coordination with other agencies, communication, and formulation of tasks;

- Considerations regarding personnel and staffing: presence of a recognized and respected champion, administrative support, and supervision.

Readiness assessment

Readiness assessment is a concept used to refer to the level of readiness of practitioners, organizations and communities to effectively implement a program (Edwards et al., 2000 in Flaspohler et al., 2008). During the exploration and preparation stages, an effective implementation strategy requires communities and organizations to assess their needs, the resources/programs in place, and the level of commitment in prevention (Mihalic et al., 2001, 2004). A readiness assessment increases the likelihood of selecting the right program to implement and helps to better understand the context in which this program will be developed.

Importance of organizational capacity and readiness

The evaluation of the Blueprints initiativeFootnote 8 indicates that most of the organizations were not ready to implement and support, with fidelity, the implementation of their program. Many program replications failed because of limited organizational capacity or an inadequate level of readiness.

(Elliott & Mihalic, 2003)

The feasibility study and readiness assessment are important steps that are too often overlooked. For example, feasibility visits conducted by Blueprints staff helped develop a better understanding of the programs, reduced feelings of fear and resistance concerning the new program, and increased motivation and confidence among practitioners (Mihalic et al., 2004).

Organizational stability, shared decision making and common vision

Lack of organizational stability (e.g., a high rate of staff turnover) is an important factor in the quality of implementation: lack of stability often delays implementation and increases the workload for remaining employees (Mihalic et al., 2004).

Situations in which decision making is shared between practitioners, researchers, administrators and community members generally leads to a better implementation as well as increased chances of sustainability. As such, research has shown a significant positive effect between community participation in decision making and sustainability (Durlak & DuPre, 2008).

Presence of a champion

The program champion is the person behind the daily program operations who motivates and facilitates communication among all those involved in the implementation. More and more, current research tends to indicate that the presence of a champion within an organization is a key component of implementation (Fixsen et al., 2006).

Generally, the director or coordinator of the program is considered the program champion. The person designated to play this role must have enough authority within the organization to be able to influence decisions and make changes to organizational structures and policies, but also needs to have relationships with the staff in charge of administering the program. Results have also shown that this person should be present on a regular basis; problems arise when this person does not have enough time to perform these tasks (Mihalic et al., 2004).

Importance of champions

At the Blueprints replication sites, those having a strong champion experienced fewer problems.

(Mihalic et al., 2004)

Sites with "dual champions," that is, one person from senior management and one person from middle management (i.e., coordination), were particularly successful in motivating staff and initiating organizational changes to accommodate the new program. In addition, these two champions often succeed in expanding the program both inside and outside of their organization (Mihalic et al., 2004).

Having multiple champions, even a team of champions, is a good strategy to adopt compared to having a single person. A team approach improves communication at all levels and develops a stronger support base within the organization. In addition, if key individuals leave the organization, others are able to take charge of the program through to its completion. For example, at the Blueprints sites, one program failed after its champion left the organization. Without a champion and active administrative support, the program was not successful (Mihalic et al., 2004).

Quality of support from management

Every successful program depends largely on the quality of support received from the management team. Administrators have the power to change organizational practices to bring them in line with new program requirements (making time, avoiding the feeling of work overload, etc.), and they have to be able to motivate and encourage staff. When practitioners feel supported, they are more motivated and inclined to implement the program and follow it with fidelity.

Importance of management support

Lack of support from the management team was the main reason why programs have failed; passivity, lack of real support and proactivity in finding solutions have been identified as common causes of failure.

(Mihalic et al., 2004)

For Blueprints programs implemented in schools, school administrators who played an active and effective role in the implementation process did the following:

- explained funding to teachers;

- sought their support prior to implementation;

- attended teacher training workshops;

- observed teachers delivering program lessons;

- kept teachers informed about the progress of the implementation;

- in some cases, co-taught lessons with the teachers (Mihalic et al., 2004).

Having administrators present for a part of or for entire training sessions increased the quality of the implementation by sending a strong message to staff that the program was a priority. By attending training sessions, administrators had a better understanding of the program, supported the program more effectively, and were able to make any necessary changes (Mihalic et al., 2004).

Coordination position

Blueprints replication sites have shown that the project coordinator position is a central position that should be undertaken by a full-time staff member (at least 20 hours per week). When this position is held by a volunteer, even someone with the proper experience and qualifications, lack of availability for the project is the variable most often cited as affecting the quality of the implementation (Mihalic et al., 2004).

Resources dedicated to evidence-based programs

There are three limitations that have been associated with challenges in implementing evidence-based programs (Gray et al., 2012):

- Lack of time: The implementation of an evidence-based intervention is often seen as supplemental to regular tasks. Time issues emerged at almost all of the Blueprints replication sites; when programs were implemented in schools, lack of time to carry out the program activities was the primary and most frequent implementation challenge (Mihalic et al., 2004).

- Limited access to research and data sources: The infrastructure to access knowledge is often limited, and practitioners have difficulty accessing the most up-to-date knowledge.

- Lack of financial resources: A lack of funding is often seen as a limitation to implement an evidence-based program.

III. Main factors related to the practitioners

Characteristics of practitioners systematically related to implementation pertain to:

- their attitudes and perceptions regarding the necessity and benefits (or not) of adopting a new program;

- their level of confidence;

- their motivation and level of commitment;

- their ability to deliver the program.

Practitioners who recognize the specific need of the program often feel more confident in their abilities (self-efficacy), and those that have the required competencies are more likely to implement it with a higher degree of fidelity (Durlak & DuPre, 2008). As noted by Greenwood & Welsh (2012), resistance from staff to adopt a new program should not be ignored: it is one thing to promote the benefits of a program to a director, but another to convince the staff to use it.

However, other research indicates that the characteristics of practitioners and their impact on the adoption and delivery of a program have produced results that are difficult to generalize (see Wandersman et al., 2008). This finding therefore demonstrates the importance of considering contextual and organizational factors and developing a better understanding of how they interrelate with program characteristics.

IV. Main factors related to the program

Results show that practitioners and organizations implement a program more effectively when (1) program objectives are consistent with the mission and values of the organization, and (2) the program is integrated into existing priorities and practices (Small et al., 2007). In several Blueprints replication sites, divergence between program philosophies and the organization's mission were identified as a major problem. At some sites, family therapists failed to respect the fidelity of the program because program directions appeared to differ from those of the agency (Mihalic et al., 2009).

"Case Studies" Section

Refer to the following case studies to obtain other concrete examples of implementation challenges and facilitators:

- Blueprints for Violence Prevention Initiative: Main challenges in the implementation process

- Obstacles of the implementation of a secondary alcohol prevention program

- Implementation of a school evidence-based substance abuse prevention program: Some examples of challenges

- School-based programs: What facilitates their implementation?

4. Key components of the implementation process

Ensuring the successful implementation of effective programs is a challenge that has gained interest for a number of years. In 2001, the principal investigators of the Blueprints for Violence Prevention Initiative published an article, "Ensuring Program Success,"which stated that the success of an implementation depended on the following elements: adequate administrative support, champion/leaders, training and technical assistance, and adequate staff (Elliott et al., 2001a,b). Since then, the use of key components for implementation has become a common practice, and current research now refers to them as "implementation drivers". Footnote 9

Implementation drivers

Are defined as the elements that positively impact the success of a program. Their presence helps to increase the probability of success in replicating a program. Key components refer to capacities, organizations' infrastructure and operations and can be classified into three categories:

- Implementation drivers related to competencies;

- Implementation drivers related to organizations; and,

- Implementation drivers related to leadership.

(Fixsen et al., 2013)

- Implementation drivers related to competencies: These are mechanisms for implementing, maintaining and delivering an intervention as planned to benefit the target clientele and the community. The implementation drivers in this category are:

- Staff selection

- Training

- Coaching

- Implementation drivers related to organizations: These are mechanisms for creating and maintaining favourable conditions in which the program will be developed and thus facilitate the delivery of effective services. The implementation drivers in this category are:

- Linkages with other external networks and partnerships

- Engagement and commitment from management

- Information management system in decision making

- Implementation drivers related to leadership: These are leadership strategies put in place to resolve various types of challenges. Many challenges relate to the integration of the new program, and leaders need to be able to adapt their leadership style (adaptive leadership), make decisions, provide advice, and support the organization's operations (technical leadership). The implementation drivers in this category are:

- Leadership (adaptive and technical)

As illustrated in Figure 2, these implementation drivers form an integrated and adjustable model. This means that, depending on conditions, one program might require more or less attention to an implementation driver, while another program, under different conditions, might be designed to eliminate one or more implementation drivers (Baker et al., 2000; Fixsen et al., 2009, 2013; Van Dyke et al., 2013). Organizations are dynamic and ever-changing and, as a result, the practical application of this model is a real challenge. In order to achieve results, there are back-and-forth movements in the contribution of each of these implementation drivers at each stage of the implementation process (see Fixsen et al., 2009). For example, in a program where only minimal basic training is offered, this could be off-set by more intense coaching along with frequent feedback. On the other hand, programs where staff have been recruited using rigorous selection mechanisms might require less coaching. We also need to recognize that practitioners acquire skills and aptitudes at different speeds and levels. One practitioner might benefit greatly from skills training and require less frequent coaching, while another practitioner might feel overwhelmed by the initial training and require more sustained coaching and supervision.

As a program is implemented, feedback and adjustment will be necessary to sustain the program. Depending on the strengths and weaknesses in place, all of the implementation drivers should be balanced and integrated.

Figure 2: Implementation drivers (adapted from Fixsen et al., 2009)

Image Description

This chart illustrates the different implementation drivers from the starting point of the Integrated and adjustable model and branching out to the following:

- Staff selection

- Training

- Coaching

- Performance evaluation - fidelity

- Linkages with other networks and partnerships

- Engagement from management

- Information management system in decision making

- Leadership

Staff selection

Staff selection is the starting point for the establishment of a qualified, experienced workforce to deliver an evidence-based program. At the Blueprints replication sites, those that hired less qualified and less experienced practitioners showed slower progress in their training and the level of ownership of the program. At these sites, staff turnover was also generally higher (lower employee satisfaction rate), which represents a significant and frequent challenge in the implementation process. More than degrees and previous experience, it is also important to consider personality traits and individual characteristics which should be included in the selection criteria (e.g., knowledge of the field, sense of social justice, ethics, willingness to learn, judgment, empathy). Some programs were developed with ease of delivery in mind in order to minimize the need for a rigorous staff selection process (e.g., tutoring program staffed by volunteers). However, other programs require staff with more complex qualifications and specific skills, and it is important to respect these criteria (Fixsen et al., 2009).

Training

Receiving adequate training is central, and everyone involved in replicating a new program should participate (practitioners, manager, administrators and others) and know how, with whom and where the new program is used (Fixsen et al., 2009, 2013). Effective training:

- Educates stakeholders/practitioners on the theory, philosophy and values of the program;

- Demonstrates and explains the rationale supporting the key elements of the program;

- Is an opportunity to apply new competencies developed;

- Proposes feedback periods.

Evaluations of school-based programs showed that, compared to untrained teachers, teachers who had been fully trained (Mihalic et al. 2004):

- Were more likely to implement the new program with a higher degree of fidelity. Among those who did not attend training, close to 50% were not successful in applying the program or abandoned it before the end of the semester;

- Completed the program more often and with greater fidelity. Fully trained teachers completed 84% of the program compared to 70% among untrained teachers, and program fidelity was 80% versus 60%;

- Felt better prepared to teach the program and received more positive results from their students.

Moreover, the evaluation of the Blueprints for Violence Prevention Initiative showed that when training and technical assistance were not adequate, replication sites had problems overcoming obstacles and the implementation was often delayed (Mihalic et al., 2004).

Coaching

Using coaching activities helps solidify ownership of the program, especially since real experimentation happens "on the ground." Specifically, the coach's role will be to make recommendations on more appropriate ways of intervening, to reinforce what was learned, provide encouragement and give feedback on skills related to the program (e.g., commitment, clinical judgment).

A study carried out by Joyce and Showers (Przybylski, 2013) shows the importance of coaching in the practical transfer of knowledge:

- 10% of newly trained staff will transfer what they learn when the training includes theory, discussions and demonstrations;

- 25% of newly trained staff will transfer what they learn when the training includes theory, demonstrations and practical workshops;

- 90% of newly trained staff will transfer what they learn when the training includes theory, demonstrations, practical workshops, and coaching.

Performance evaluation – fidelity

Performance evaluation is as much about evaluating the performance of practitioners delivering the program and adherence to the program (fidelity) as it is about the achievement of expected results (Metz et al., 2007). Those in charge will measure the performance of practitioners and program compliance to identify training needs, redirect program actions if necessary, and obtain information about overall performance.

Linkages with other external networks and partnerships

Partnerships and coordination with other external networks is central, at all stages of the implementation process. Linkages with different systems are not only useful for resource sharing and availability but also for facilitating the recruitment of program participants through referral mechanisms and for the development of a comprehensive treatment plan (Mihalic et al., 2004).

Engagement and commitment from management

The engagement and commitment of management refers to its leadership and its ability to make decisions based on the data collected and to facilitate the processes through which the program will be implemented. Management that is engaged and committed to the program will act to bring directions and practices in line with the expected program results (Fixsen et al., 2005, 2013). When management is fully committed to program implementation, policies, procedures, structures, culture and climate will be aligned with the needs of practitioners in order to develop favourable conditions to deliver the program (Fixsen et al., 2009). Working in a positive environment where the program is understood and where management provides flexibility to change work routines are two very important elements.

Information management system in decision making

Collecting information (e.g., interventions, fidelity, client satisfaction, staff assessment, target group reached) is another key element that helps provide an overview of performance and supports decision making. Progress and summary activity reports provide directions for decision making, assist organizations in delivering the program, indicate whether corrections need to be made, and inform on the quality of the interventions.

Leadership

The essential role of a leader within the organization and with external networks is widely recognized (Fixsen et al., 2013). Leadership is not assumed by a single individual but by people who are involved in various activities and who adopt behaviour associated with leadership to establish effective programs and support them over time. In the first stages of implementation, an "adaptive" leadership style will be necessary to deal with changes resulting from the new program; this style of leadership will continue to be important throughout the implementation process. Later, "technical" leadership will become more predominant in order to manage and support the implementation (e.g., selection interviews, performance evaluations, collaborative agreements with external networks). Sometimes the same people provide these two types of leadership; other times leadership is more broadly distributed throughout organizations (Fixsen et al., 2013).

"Case Studies" Section

Process evaluations of programs supported as part of the Blueprints for Violence Prevention Initiative also identified key elements of the successful implementation of programs to prevent violence, delinquency and drug use:

5. Implementation teams

Implementation is an active process, and it is important to have individuals dedicated exclusively for that purpose. Over the years, different terms have been used to identify these individuals: for example, liaison officer, program consultant, site coordinator. The NIRN and SISEP Footnote 10 networks use the term "implementation teams," and recent research increasingly shows the importance of having dedicated people within the organization (or outside the organization) designated to carry out the central activities related to program implementation.

Implementation teams

Are generally made up of three to five people who have program expertise and knowledge of the principles of implementation, improvement cycles and methods of organizational change. Implementation teams have allocated time so that they can be fully engaged in the development of the infrastructure needed for implementation.

(NIRN, SISEP)

Some implementation teams are composed of program developers and providers, others are intermediary organizations that assist in implementing a variety of programs, while still others are formed on site with the support of groups outside the organization. Regardless of their composition or their name, it is especially important to have the necessary expertise and resources to:

- ensure the use of the implementation drivers;

- follow the implementation process;

- establish connections between partners; and,

- facilitate internal changes for integrating the new program into the organization's existing structure (Fixsen et al., 2006; Mihalic et al., 2004). Footnote 11

6. Fidelity in program implementation

One of the strengths of evidence-based programs is being able to demonstrate, through rigorous evaluation studies, the capacity to produce and reproduce positive changes among participants. For policy makers, funders, and practitioners, these programs become the new way to provide services as opposed to some traditional programs for which the results are sometimes mixed. However, a program will only continue to produce the same results if it is implemented in accordance with the original program (O'Connor et al., 2007).

What is program implementation fidelity?

In its simplest form, implementation fidelity, sometimes called adherence or integrity, refers to how the program is implemented in relation to its initial design, the delivery of all of the program's key components, and the use of protocols and tools specific to the program.

(Mihalic, 2004b)

Although some authors have made recommendations for the adaptation of programs (Rogers, 1995), the majority of data collected from meta-analyses and evaluations demonstrate that programs implemented with greater fidelity have a greater likelihood of producing the expected changes (Fixsen et al., 2009; Mihalic et al., 2004b). According to Perepletchikova and Kazdin (2005), an implementation fidelity rate over 80% indicates a high-fidelity implementation (in Stern et al., 2008). Various factors affect the level of fidelity and the following elements help maintain a high level of fidelity in program implementation: staff training, well-developed program manuals, organizational support, supervision, and program monitoring (Stern et al., 2008).

The Washington State Institute for Public Policy Evaluation (Washington, United States) conducted a study on the Functional Family Therapy (FFT) program comparing the recidivism rate of participants (followed over 18 months) correlated with practitioners' adherence to the program. Results are clear: the more practitioners adhered to the program, the lower the recidivism rate:

- (Recidivism rate for the control group: 28%)

- Recidivism rate for the group of practitioners who were highly adherent: 18%

- Recidivism rate for the group of practitioners who were "just" adherent: 23%

- Recidivism rate for the group of practitioners who were "borderline" adherent: 31%

- Recidivism rate for the group of practitioners who were not adherent: 34%

Five aspects of fidelity

The definition of fidelity proposed by the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (CSAP, 2001) is the degree to which the elements of a program, as designed by its developer, match its actual implementation by an organization. Based on this definition, program fidelity is measured according to five variables (Dane & Schneider, 1998 in Mihalic, 2004b):

- Adherence: Determines whether the program is implemented as designed (i.e., delivery of all of the key components to the appropriate population, staff training, use of protocols, tools and material, selection of replication sites, etc.).

- Exposure: Includes the following elements: number of sessions, length of each session, and frequency of using techniques of the program.

- Quality of program delivery: Refers to the manner in which the program is delivered by practitioners (e.g., teacher, volunteer or program staff); this can include the ability to use the prescribed methods or techniques of the program, the level of readiness, and attitudes.

- Participant responsiveness: Measures how engaged and involved participants are in program activities.

- Program differentiation: Identifies the unique characteristics of the program (when the program's reliability is distinguished from others).

Program adaptations

Although there is no denying that it is preferable to replicate the program with fidelity, a program may be adapted without affecting its key components and compromising the expected results. The table below presents examples of acceptable versus unacceptable (risky) adaptations. Adaptations that affect the key components of the program (such as modifying dosage, theoretical approach and staff) are considered risky adaptations as they jeopardize the achievement of the program's expected results. Understanding key components of the program is a central part of program adaptation: failure to adhere to them may lead to what is referred to as "program drift." Moreover, it is better for adaptations to be made after a first wave of pilot tests in order to demonstrate that the program has the capacity to achieve the expected results (Przybylski, 2013) and adaptations should always be indicated and monitored through performance data and evaluations.

| Acceptable adaptations | Unacceptable (risky) adaptations |

|---|---|

|

|

In order to better identify the consequences of adapting a program, new research needs to be conducted to determine which elements are imperative and must be executed with fidelity and which elements can be modified. Implementation studies should also specify the components that were reproduced with fidelity and those that were modified; without these details and these results, it will continue to be difficult to measure the effects of adaptations on program results.

"Case Studies" Section

For additional concrete examples of different types of adaptations and examples of obstacles and facilitators to program adhesion, refer to the following case studies:

7. Findings on the implementation of crime prevention programs

Concepts of implementation that have been presented so far are generalizable, meaning they are central to implementation regardless of the nature of the program. But are there specific key components and characteristics for the implementation of crime prevention programs? Certain obstacles related to the target group (identification, recruitment and retention of participants) illustrate how and why the implementation of prevention programs is different. It is also important to stress that crime prevention programs work with a clientele that has multiple risk factors, sometimes even criminal records, which raises a series of implementation challenges that seem to be specific to the crime prevention programs.

Participant identification

Identifying people with the right profile to participate in a program can be a real challenge, depending on the context and nature of the program. Before accepting a person into a program, risk levels and problems need to be analyzed. Eligibility to participate in a program, particularly when it is a prevention program targeting an at-risk clientele, should be evidence-based. To this end, there are validated tools to identify and assess risk, and the use of these tools is strongly encouraged. Footnote 12 With the results obtained using these tools, it is possible to develop individualized intervention plans and obtain measures of progress/change among participants (using pre/post-test measures). Identifying risk levels and main risk factors enable crime prevention programs to not only standardize certain practices but also to ensure that interventions are targeted. Even knowing that the use of screening and risk assessment tools presents challenges in itself, using them is still beneficial for crime prevention programs. In this way, having validated screening and risk assessment tools represents a specific key component in the implementation of crime prevention programs.

Participant recruitment

Recruiting participants into the program is another challenge. In addition to people who join of their own accord, recruitment is also done through a referral system set up between partners from various organizations (e.g., police, health and social services network, addiction treatment centres, schools, mental health organizations). The creation of this referral system takes time and needs to be supported by administrations in order to facilitate and encourage the referral processes. Other difficulties arise with sharing confidential information (e.g., youth protection file, file involving criminal charges, a health and social services file). To regulate and secure these referrals, memorandums of understanding and confidentiality practices should be put in place, and administrations must support them. Challenges associated with the establishment of referral and information sharing systems impact the entire implementation process by delaying the initial implementation stage, and, in some cases, partners may decide to withdraw from the project. Establishing strong rules for collaboration with the right key partners and being supported by a committed and flexible administration are two other essential components specific to crime prevention programs.

Participant retention

Generally, participation in crime prevention programs is voluntary and the length of participation varies depending on the program. In programs with a family-oriented approach, parents' participation is central, and this creates similar recruitment, engagement and retention problems. To encourage participation and program completion, retention strategies should be proposed (e.g., offering gift cards, providing snacks, making transportation available), and this would represent another key component specific to crime prevention programs.

These examples of challenges associated with the target group represent a central point of crime prevention programs and should receive a special focus. Other examples of challenges related to the implementation of crime prevention programs can also be mentioned, including: fidelity in the implementation, program adaptation (and cultural adaptation), selection and retention of qualified staff, training and technical support (especially for foreign programs).

All of these challenges, in addition to slowing down the implementation process, also affect the achievement of the expected outcomes. Abandoning or not completing the program, a low participation rate or high attrition rate, or a poor mix of people in one cohort affect program outcomes. Even if the program is classified as a model program, all of these implementation challenges can negatively impact measures of effectiveness. Concretely speaking, poor impact results would imply that this program is not effective when these results may in fact be due to practical problems related to the implementation. From the point of view of public investments in prevention, there are major implications, including: experiencing difficulty promoting this program in the future and implementing it in other replication sites (in order to confirm that this program really doesn't work in a Canadian context) as well as sustainability problems.

The implementation process needs to be an integral part of prevention programs. Without distinguishing between implementation problems versus those that arise from the program itself (e.g., limited information on key components), it would remain difficult to make reliable and valid judgments on the reasons explaining why a program did not achieve the expected outcomes. Implementation is a complex process and challenges are always expected. However, some challenges can be identified in advance and facilitative strategies can be put in place to mitigate them.

The importance of high-quality implementation is a central dimension for practitioners, researchers, decision makers, funders as well as for individuals participating in a program. Unless specific attention is given to the quality of a program's implementation, large-scale programs are unlikely to be effective. Detailed analyses on the implementation of crime prevention programs should be maintained and pursued in order to better understand their specific characteristics and challenges and to identify appropriate facilitative strategies.

Planning Tools

Checklists of activities related to implementation stages

This planning tool, in the form of checklists of activities related to the implementation stages, is useful for evaluating, planning and monitoring implementation activities across each stage of the process. Even though these stages may appear linear, they are not: one stage does not end sharply as another begins. Back-and-forth movements between stages occur and are encouraged when core activities are not completed. Table 3 presents all activities according to the four stages of implementation and their delivery stages. This table also illustrates that many activities continue over time. Following this table are definitions for the activity categories used.

The purpose of this section is to provide organizations with a tool so that they are able to plan and develop an implementation plan tailored to the program, local conditions and organizational capacity. Awareness of all of the activities at each implementation stage also helps to identify strengths and weaknesses in order to better determine where challenges might arise and where additional efforts may be required.

| Stage 1 Exploration and Adoption |

Stage 2 Preparation and Installation |

Stage 3 Initial Implementation |

Stage 4 Full Implementation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organization | X | X | X | X |

| Assessment (needs/capacities) | X | |||

| Program selection | X | |||

| Implementation team | X | X | X | X |

| Communication strategy | X | X | X | X |

| Resources | X | X | ||

| Partnerships and collaborations | X | X | ||

| Operational details of the program | X | X | X | |

| Organizational culture and climate | X | X | X | |

| Human resources – staff | X | X | X | |

| Information management system | X | X | X | |

| Sustainability | ||||

Definitions of the activity categories:

Organization: Includes activities related to the creation of the implementation team, final selection of the program(s), structural and operational changes to be made to the organization, use of improvement processes, development of responses to program drift, and answers to program modification/adaptation questions.

Assessment of needs/capacities: Includes completion of an assessment to determine community needs/resources and an assessment of organizational capacity.

Program selection: Includes activities such as identification and revision of eligible programs, analysis of results, and final selection of the program.

Implementation team: Group of individuals responsible for with providing guidance throughout the full implementation by ensuring commitment, laying the groundwork, ensuring program fidelity, and monitoring results, challenges and facilitators.

Communication strategy: Development and maintenance of a clear, consistent and frequent communication strategy.

Resources: Refers to all activities related to securing resources (financial, material, human and other) for the program's implementation.

Partnerships and collaborations: Refers to all activities related to the involvement of stakeholders in the implementation process, including identification and involvement of "champions" and identification of partners and opportunities for collaboration.

Operational details of the program: Includes liaison activities with program developers, identification and preparation of implementation sites, establishment of a participant referral system and recruitment process, identification of facilitators, and response to implementation challenges.

Organizational culture and climate: Includes activities to assess and manage an organization's readiness to change in order to implement the new program.

Human resources – staff: Refers to activities involving staff who execute the program, including selection, training, developing training plans, coaching and supervision processes, and technical assistance/support.

Information management system: Includes the development and maintenance of a data system to collect information and measure effects by reporting fidelity and performance, as well as ensure quality maintenance.

Sustainability: Sustainability is not a discrete stage. Rather, it needs to be planned from the beginning and reviewed at each stage. Activities include securing ongoing funding, developing new partnerships and sharing successes, maintaining implementation with fidelity, and supporting continuous improvements to the program.

| Stage 1: Exploration and Adoption | Completed/ In Place |

Initiated/ Partially in Place |

Not Addressed/ Not in Place |

Comments/ Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Conduct assessments (needs/capacities):

|

||||

Select a programFootnote 15 and make a final decision:

|

||||

Establish an implementation teamFootnote 17:

|

||||

Develop a communication strategy:

|

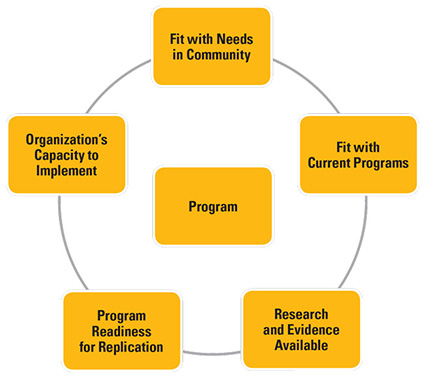

Figure 3: The Pentagon Tool Footnote 18

Image Description

This chart illustrates the Pentagon Tool program which consists of the following parts:

- Fit with Needs in Community,

- Fit with Current Programs,

- Research and Evidence Available

- Program Readiness for Replication, and

- Organization's Capacity to Implement

Program

- Brief overview of the program and its goals

- Target population

- Risk and protective factors addressed

- Replication site requirements

- Staffing and volunteers requirements (qualifications and experience)

- Training requirements (mandatory/optional)

- Coaching and supervision process

- Implementation manuals, guides, tools, etc., required

- Administrative support, data systems, other technology required

- Resources needed (financial/in-kind)

Fit with Needs in Community

- Addresses identified need(s)

- Fits with target group(s) and area(s) identified

- Matches with replication site(s)

Fit with Current Programs

- Fits with/complements current programs to address need(s) identified

- Fits with organizational structure and priorities

- Fits with community values

- Community cultural/linguistic compatibility

Research and Evidence Available

- Program is rated by registries/databases

- Research to support the program theory model

- Number of research and evaluation studies conducted

- Outcome measures available

- Fidelity data available

- Cost-effectiveness data available

- Population similarities to target population identified

- Applicable to diverse cultural groups (Aboriginal)

- Rating of efficacy or effectiveness

Program Readiness for Replication

- Availability/support of program developer(s)

- Training and technical assistance

- Possibility to observe program's effects in other sites, other successful replications, adaptations

- Level of effort to implement, certification/licence required

- Potential implementation challenges identified

Organization's Capacity to Implement

- Site availability, staffing and volunteer supports, training requirements, coaching and supervision, administrative support data systems and technology required, resources (financial/in-kind)

- Sustainability – organizational commitment and financial resources

- Community buy-in – support of necessary partners

| Yes | Partially | No | Comments/Details | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program fits with needs in community | ||||

| Program fits with current programs | ||||

| Research and evidence available | ||||

| Program readiness for replication | ||||

| Organization's capacity to implement | ||||

| Overall Rating |

| Stage 2: Preparation and Installation | Completed/ In Place |

Initiated/ Partially in Place |

Not Addressed/ Not in Place |

Comments/ Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Connect with program developer(s) on the following topics:

|

||||

Obtain and secure all resources:

|

||||

Identify and engage champions:

|

||||

Assess the organization's culture and climate:

|

||||

Make structural and functional changes to the organization (as needed):

|

||||

Engage implementation teamFootnote 19:

|

||||

Identify and prepare appropriate implementation site(s):

|

||||

Identify partners and opportunities for collaboration:

|

||||

Determine the referral process and initial participant recruitment:

|

||||

Maintain a communication strategy:

|

||||

Select program delivery staff:

|

||||

Begin training and supervision:

|

||||

Establish a data system to collect information and measure effects:

|

| Stage 3: Initial Implementation | Completed/ In Place |

Initiated/ Partially in Place |

Not Addressed/ Not in Place |

Comments/ Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Establish initial program implementationFootnote 21:

|

||||

Implement the referral process and recruitment of participants:

|

||||

Establish a coaching plan and staff supervision process:

|

||||

Manage the organization's culture and climateFootnote 22:

|

||||

Maintain a data system to collect information and measure effects:

|

||||

Review initial implementation challenges and facilitators:

|

||||

Maintain a communication strategy:

|

| Stage 4: Full Implementation | Completed/ In Place |

Initiated/ Partially in Place |

Not Addressed/ Not in Place |

Comments/ Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Establish full program implementationFootnote 24:

|

||||

| Continue to monitor and improve systems already in place: | ||||

| 1. Referral and recruitment of participants | ||||

| 2. Staffing, training and booster training, technical assistance | ||||

| 3. Program delivery – key components and activities | ||||

| 4. Organizational culture and climate | ||||

| 5. Coaching plan and staff supervision | ||||

| 6. Fidelity measures and reporting processes | ||||

| 7. Outcome data measures and reporting process | ||||

| 8. Quality assurance mechanisms | ||||

| 9. Partnerships, collaboration and resources | ||||

| 10. Communication strategies | ||||

Employ improvement processes:

|

||||

Address organizational response to drift:

|

||||

Address program modification/adaptation:

|

||||

| Sustainability | Completed/ In Place |

Initiated/ Partially in Place |

Not Addressed/ Not in Place |

Comments/ Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Establish ongoing funding:

|

||||

Establish new partnerships and share successes:

|

||||

Maintain implementation fidelity:

|

||||

Support continued improvement of program:

|

Case Studies

1. Blueprints for Violence Prevention Initiative: Main challenges in the implementation process

The replication sites for programs under the Blueprints for Violence Prevention Initiative tended to face similar challenges at roughly the same moments in the implementation process:Footnote 25

Initial challenges for program implementation

The initial challenges are generally the most complex and take time to overcome. These challenges generally occur within the first four to eight months and include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Completion of a multitude of administrative tasks;

- Fundraising;

- Hiring program staff and preparing training;

- Management of professional insecurities;

- Development of inter-organizational links and partnership/collaboration agreements.

Subsequent challenges for program implementation

After one year of implementation, challenges associated with initial stages of implementation are generally resolved; however, as implementation progresses, other types of challenges arise:

- Persistent challenges: These are challenges that have been present since the beginning but for which levels of difficulty and stress have diminished (e.g., more professional confidence, forms regularly completed). These stresses, even though they are still present, very rarely threaten the continuity of the project.

- Episodic challenges: These challenges include staff turnover, personality conflicts and administrative changes within the organization. These challenges require time and energy but usually resolve themselves once a solution is put in place (e.g., hiring new practitioners, better training, better understanding of the program, better referral system).

- Threatening challenges: These challenges arise when dramatic changes take place (e.g., budget cuts, loss of champions, damaged relationships with partners) or when prominent persons are opposed to the philosophy behind the program. These challenges could jeopardize the integrity and continuity of the program.

These results lead us to believe that certain challenges are associated with a specific stage of implementation. Table 4 provides an overview of the four stages of the implementation process and summarizes what appears to be the most common challenges at each of the implementation stages. This information is based on research conducted by Fixsen and his colleagues (2005) and the results of the Blueprints for Violence Prevention Initiative (Mihalic et al., 2003).

| Stage 1 – Exploration and adoption |

|---|

|

| Stage 2 – Preparation and installation |

|

| Stage 3 – Initial implementation |

|

| Stage 4 – Full implementation |

|

| Sustainability |

|

2. Obstacles of the implementation of a secondary alcohol prevention program

This studyFootnote 26 explains obstacles related to the implementation of the Alcochoix+ program aimed at heavy drinkers. The objective of this evaluation was to answer the question: "What are the obstacles that were encountered during the implementation of this program?" The main obstacles encountered during implementation are as follows:

- Deficiencies in advertising and promotion: Small amount, non-recurring and lack of coordination. Simply distributing pamphlets was not enough and lack of coordination with other programs promoting healthy lifestyles was also criticized.

- Lack of human and financial resources: Little financial investment in the program (compared to the costs of excessive alcohol consumption).

- High staff turnover at all levels: Among practitioners and management as well as respondents at the regional level. This situation resulted in a service void, led to increased need for training, and was also responsible for confusion in identifying individuals involved in the program as well as roles and responsibilities.

Then comes the lack of leadership in program management, lack of communication (poor flow of information), lack of time that practitioners could dedicate for the program, lack of knowledge about the program's existence (within the organization as well as outside in the health network) and lack of knowledge about the program's underlying approach. Finally, the lack of access to training outside major urban centres, the low volume of participants and lack of monitoring were other challenges identified.

3. Implementation of a school evidence-based substance abuse prevention program: Some examples of challenges

An initiative,Footnote 27 funded over five years, dealt with the implementation in three school districts of an evidence-based substance abuse prevention program called the "Michigan Model for Comprehensive Health Education". Traditional impact evaluation measures show that this program did not have a significant impact, and its failure to obtain results is discussed in relation to major challenges related to its implementation.

Inappropriate program selection: The choice of program to be implemented is an important step. To select the most appropriate program, it is crucial to understand the needs of the target population and available resources/services. A program that was effective in one school district will not necessarily be effective in others.

To increase good fit into program selection:

- A close match is needed between the program's theory of change and the particular needs of the target population.

- Practical questions have to be taken into consideration: What is the length of the program/cost? What are the required qualifications for staff? What is the training/cost? Is the material available/cost? If the financial resources are not available or if it is too hard to make time for staff training, it is not likely that the program will be implemented successfully.

Limited engagement of partners and low level of schools' readiness: The success of the program's implementation in schools depends not only on teachers but also on support given from school board administrators, principals, social workers, parents and the community. The lack of partners' engagement was identified as a significant obstacle. Also, the level of effort made by schools in preparing the implementation was not sufficient and various tasks were underestimated, particularly those pertaining to preparing and planning resources and strategies that aimed to integrate the program in the school calendar without making teachers feel overloaded.

To increase the probability of success during implementation:

- Staff support and acceptance of the program is central so that the individuals involved are willing to put forth time and energy;

- Strong leadership from management to ensure implementation is monitored and assistance is provided (particularly when obstacles arise);

- Positive and flexible work environment;

- Creation of an internal team of "champions" that will support the introduction, implementation and improvement of the program.

Low implementation fidelity: Results of program evaluation showed that implementation fidelity was not conducive to program success. For example, lessons and activities were omitted while others were combined to "save time." The program curriculum as designed and validated by the Michigan developers was not respected.

To increase the probability of successful implementation fidelity:

- The program must be followed and delivered as designed (adherence to curriculum);

- Training and adequate support must be available;

- If adaptations need to be made, they must be discussed with program developers to ensure that these changes will not affect core components of the program;

- Staff members must be comfortable delivering the program activities and lessons.

4. School-based programs: What facilitates their implementation?

Through consultation with Anglophone and Francophone experts in Quebec on various school-based programs,Footnote 28 it was possible to identify favourable implementation conditions as well as their main challenges.

Implementation facilitators of school-based programs:

- Importance of having a coordination structure;

- Crucial role of management;

- Funding (particularly funding from the school network) to facilitate the purchase of materials and training;

- Support from the school board and partners concerning planning and program improvements;

- Quality of training;

- Quality of support provided by program developers; this also represents a favourable strategy to maintain community engagement and develop intervention skills related to the program.

Implementation obstacles of school-based programs:

- Heavy workload (combined teaching and intervention requirements), and lack of time;

- Instability and turnover of school staff and partners;

- Demands of working in partnership;

- Difficulty engaging parents in the program.

5. Blueprints for Violence Prevention Initiative: Key elements of a high-quality implementation

The following elements are taken from the process evaluations of the Blueprints for Violence Prevention Initiative Footnote 29,Footnote 30 and are central to an effective and successful program implementation:

- Increase site readiness: Develop an environment that is favourable to the new program, initiate an implementation plan, and ensure that there are adequate and appropriate resources (financial, material, human) for the program.

- Build organizational capacity: Develop active and engaged administrative support, strengthen internal stability, establish the inter-organizational links necessary for the program, and develop formal engagement agreements.

- Focus on supporting staff: Include staff in planning and decision making processes, hire staff with required skills and qualifications, strengthen skills through training offered as part of the new program, and provide time needed to deliver the integrality of the program.

- Designate champion(s).

- Ensure that training and technical assistance are available.

- Understand the importance of implementing the program with fidelity.

6. Program adaptations based on implementation contexts: Some findings

The following are some of the key findings taken from a study on the adaptation of evidence-based programs based on the implementation contexts.Footnote 31

Frequency of adaptations:

- Programs implemented in schools are the most frequently adapted (close to 50% of respondents reported having adapted the program), while family therapy programs are the least often adapted (25% of respondents).

Nature of adaptations:

- The type of adaptation varies based on the nature of the program and context. For example:

- Community and mentoring programs tend to adapt procedures most frequently (60%);

- School programs: dosage and content in similar proportions (close to 55%);

- Family therapy programs: target group (close to 30%);

- Prevention programs for families: cultural adaptations (30%).

Reasons for adaptations: