2016-2017 Horizontal Evaluation of the National Action Plan to Combat Human Trafficking (NAP-HT)

Table of contents

- Executive Summary

- What We Examined

- Why Is This Important

- Purpose, Scope, and Methodology of the Evaluation

- Limitations

- Evaluation Findings: Relevance

- Evaluation Findings: Performance - Governance and Data Sources

- Evaluation Findings: Performance - Four Pillars

- Evaluation Findings: Performance – Costing

- Conclusions

- Recommendations

- Management Response and Action Plan (MRAP)

- Annexes

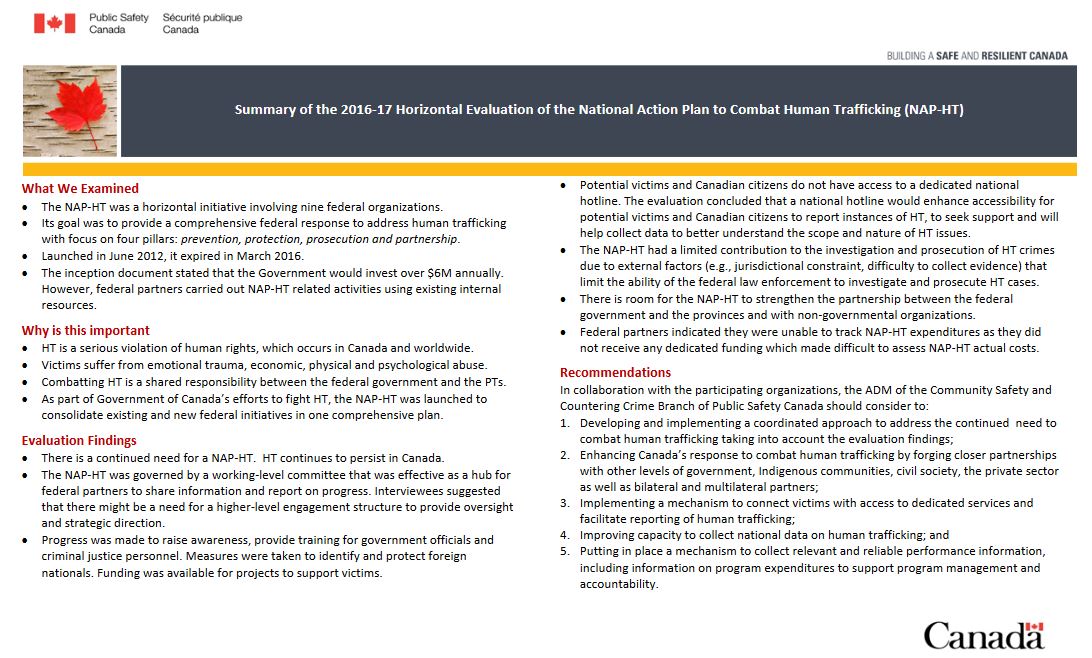

Executive Summary

The NAP-HT was a horizontal initiative involving nine federal organizations with the goal of providing a comprehensive federal response to address human trafficking with focus on four pillars: prevention, protection, prosecution and partnership.

- The evaluation found:

- There is a continued need for a NAP-HT as human trafficking continues to persist in Canada.

- The working-level committee was an effective hub for federal partners to share information and report on progress.

- Progress was made to raise awareness, provide training for government officials and criminal justice personnel.

- That a national hotline would enhance accessibility for potential victims and Canadian citizens to report instances of HT, to seek support and will help collect data to better understand the scope and nature of HT issues.

- The NAP-HT had a limited contribution to the investigation and prosecution of HT crimes due to external factors.

- There is room to strengthen the partnership between the federal government and the provinces and with non-governmental organizations.

- Federal partners were unable to track NAP-HT expenditures as they did not receive any dedicated funding.

- The evaluation recommends the ADM of the Community Safety and Countering Crime Branch should consider :

- Developing and implementing a coordinated approach to address the continued need to combat HT taking into account the evaluation findings;

- Enhancing Canada’s response to combat HT by forging closer partnerships with other levels of government, Indigenous communities, civil society, the private sector as well as bilateral and multilateral partners;

- Implementing a mechanism to connect victims with access to dedicated services and facilitate reporting of HT;

- Improving capacity to collect national data on HT;

- Putting in place a mechanism to collect relevant and reliable performance information, including information on program expenditures to support program management and accountability.

What We Examined

- The NAP-HT was a horizontal initiative involving nine federal organizations:

- Public Safety Canada (lead), the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Justice Canada, Canada Border Services Agency, Employment and Social Development Canada, Global Affairs Canada, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, Status of Women Canada, and Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada.

- Launched in June 2012, the NAP-HT expired in March 2016.

- The overall goal of the HAP-HT was to provide a comprehensive federal approach to address human trafficking by focusing on four pillars: Prevention, Protection, Prosecution, and Partnership.

- The aim of the four pillars is to prevent trafficking from occurring, protect victims of human trafficking, bring its perpetrators to justice and build partnerships domestically and internationally.

- The NAP-HT stated that the Government would invest over $6M annually on Human Trafficking activities (it should be noted that participating organizations did not receive any new, dedicated funding for this purpose, but rather were expected to carry out NAP-HT related activities using existing internal resources).

Why is this important?

- Human trafficking is a serious violation of human rights occurring in Canada and worldwide.

- Victims of human trafficking suffer from emotional trauma, as well as economic, physical and psychological abuse.

- Combatting human trafficking is a shared responsibility between the federal government (e.g. national leadership, legislative authority over the criminal code, border control, international collaboration) and provincial/territorial governments (e.g. social and health services, administration of criminal justice including law enforcement).

- As part of the Government of Canada’s commitment to fight human trafficking, the NAP-HT was launched to consolidate existing and new federal initiatives into one comprehensive plan.

Purpose, Scope, and Methodology of the Evaluation

- The inception document called for a horizontal evaluation to be conducted in 2016-17.

- The evaluation assessed the relevance and performance of the NAP-HT from June 2012 to March 2016.

- The evaluation was conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board Policy on Results and the Directive on Results.

- The evaluation used the following lines of evidence:

- literature and program document review;

- analysis of performance information and financial data; and

- interviews with partner organizations (n=40) (including program staff and management) and external representatives (n=21) (including provincial government representatives, law enforcement representatives, non-governmental organizations, subject matter experts).

- Evaluators in each participating organization conducted their organizational-related interviews and other activities in support of this evaluation.

Limitations

- There was limited performance and financial information available (participating organizations attributed this to the absence of dedicated funding). This constrained the evaluation’s ability to fully assess the effectiveness of anti-human trafficking efforts conducted under the NAP-HT. As a mitigating effort, the evaluation relied mostly on the opinion of the interviewees and program document review.

- The evaluation team did not solicit the perspectives of the victims of human trafficking owing to certain sensitivities. The evaluation mitigated the impact of this limitation by conducting interviews with representatives of non-governmental organizations who work closely with these victims and through document and literature review.

Evaluation Findings: Relevance

Key Findings: Relevance – Need

Findings: There is a continued need to have a national strategy to combat human trafficking. There are opportunities for the NAP-HT to evolve.

- There is a continued need to have a national action plan:

- Human trafficking is a persistent phenomenon in Canada:

- Literature review indicated that human trafficking in Canada involves a diverse range of victims (women, children, men), circumstances (sexual, labour exploitation), locations (large urban centres, smaller cities and communities), and perpetrators (individual, family-based, organized criminal networks).

- The U.S. Trafficking in Persons reports identify Canada as a source, transit, and destination country for sex trafficking, as well as a destination country for forced labor. People are trafficked to and from Canada, which means that human trafficking has both domestic and international components.

- According to official available data from Statistics Canada, there were 396 victims of police-reported human trafficking incidents and 459 persons accused of human trafficking between 2009 and 2014.

- However, there is consensus in the literature and among interviewees that there is a high-degree of underreporting and that the problem of human trafficking is likely to be bigger than the police-reported figures.

- There is a continuing need to have a NAP-HT in order to consolidate federal initiatives, for federal organizations to partner together, and to strengthen accountability:

- Prior to the NAP-HT, each federal organization conducted its own anti-human trafficking initiatives. The NAP-HT consolidated federal initiatives to combat human trafficking under one plan;

- Interviewees revealed that because human trafficking is addressed by many different federal organizations, there is a continuing need for federal organizations to partner together; and

- The NAP-HT is needed to assess and report progress made on a continuing basis.

- The NAP-HT is required to meet Canada’s ongoing international commitments to combat human trafficking:

- Through the NAP-HT, Canada effectively implemented the various provisions of the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, Supplementing the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime.

- In addition, through the NAP-HT, Canada was able to implement several commitments in the UN Global Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking in Persons.

- If the NAP-HT did not exist, Canada would not be meeting the standards set by other like-minded countries (USA, UK, Australia, Ireland, and Netherlands) which have national action plans in place.

- According to the 2016 U.S. Trafficking in Persons report, Canada was listed among the 30 top-rated countries in the fight against human trafficking that either have a current or a recently expired national action plan or are in the process of developing one.

- There are opportunities for the NAP-HT to evolve:

- Strengthening the partnership with the provinces/territories and other stakeholders:

- External interviewees commented that when the NAP-HT was implemented, the pattern of human trafficking was relatively unknown and that having a “federal” response was a good start. However, they also noted that there is a need for developing a closer partnership among all levels of government and other stakeholders to bring about a coordinated national response:

- Given the launch of the Ontario anti-human trafficking strategy in 2016, together with the other provincial efforts (e.g. Manitoba, British Columbia), it is important to ensure that there is alignment between federal and provincial responses.

- There is also a need to forge closer collaborations with Indigenous communities, non-governmental organizations, frontline service providers, and researchers, as well as establishing ties with the private sector (e.g. banks, airlines, hotels) and social service organizations (e.g. doctors’ offices).

- Adapt to emerging trends in human trafficking:

- Interviewees suggested that the NAP-HT should put more emphasis on labour trafficking, persons with disabilities, gender-based perspective as it relates to LGBTQ2S, under-age boys as sexual victims, women as perpetrators, and forced marriages.

- Internationally, the NAP-HT should further take into account issues such as the vulnerabilities of irregular migrants to trafficking, trafficking in situations of conflict (e.g. exploitation of children by armed groups) and trafficking in the global supply chains, particularly those of Canadian businesses and government contractors.

Key Findings: Relevance – Priorities

Findings: The NAP-HT is aligned with federal government priorities.

- Human trafficking is directly or indirectly linked to other governmental priorities:

- Budget 2017 proposed to establish a National Strategy to Address Gender-Based Violence ($100.9M over 5 years and $20.7M per year thereafter). It described gender-based violence as “a persistent problem”, and that “women and girls are more likely to be victims of human trafficking for the purposes of sexual exploitation.” In addition, under the Urban Indigenous Strategy, it is stated that “Indigenous women and girls are three times more likely to be victims of violence and are more likely to be victims of human trafficking or the sex trade.”

- The mandate letter to the Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada required “an inquiry into murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls in Canada” to be conducted in collaboration with the Minister of Justice along with the support of the Minister of Status of Women. As part of this, the inquiry was asked to address the sexual exploitation and trafficking of Indigenous women and girls and their causes and consequences, and consider the historical links to organized crime including prostitution, gangs, human trafficking and drugs.

- Canada has made strong international commitments to combat human trafficking:

- In 2015, Canada committed to implement the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, including the delivery of three targets related to human trafficking:

- Target 5.2 – eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls, including trafficking and other types of exploitation;

- Target 8.7 – take measures to eradicate forced labor, end modern slavery and human trafficking; and

- Target 16.2 – end abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against children.

- One of the key deliverables resulting from the inaugural meeting at the North American Working Group (Mexico, Canada, and USA) on Violence against Indigenous Women and Girls was “to reduce human trafficking of Indigenous women and girls across North American borders”.

- In 2015, Canada committed to implement the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, including the delivery of three targets related to human trafficking:

Key Findings: Relevance – International Comparison and Best Practices

Findings: When compared to other like-minded countries, Canada’s approach to combat human trafficking is similar. However, the evaluation identified some best practices that could complement Canada’s efforts to combat human trafficking.

- The USA, UK, Australia, Ireland and the Netherlands have national action plans using an inter-agency approach.

- The evaluation identified opportunities for Canada to adapt international best practices such as:

- Using a whole-of-society approach to engage all relevant stakeholders:

- In Canada, the NAP-HT involved mostly the federal institutions. This differs from other like-minded countries where the civil society stakeholders (e.g. non-governmental organizations, unions), regional and local law enforcement, the private sector, and survivors of human trafficking all play more prominent roles.

- Enhancing accessibility to report human trafficking and for victims to seek support:

- Interviewees and literature review revealed the importance of having an accessible point of contact through which potential victims can report human trafficking-related incidents and seek support.

- In the USA, through the Polaris Project, there is a dedicated national hotline to report human trafficking (999) and a text line with the word "BeFree". Mexico and the UK also have national hotlines assisted by the Polaris Project.

- An added benefit of having a national hotline is to allow the country to collect data to learn more about the scale and nature of human trafficking in the country. This is currently the case in the USA, the UK and Mexico.

- Having top leadership engaged to combat human trafficking:

- The US Presidential Inter-Agency Task Force to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons is chaired by the Secretary of State and includes officials at the cabinet level from 15 departments and agencies. Agencies report annually on progress made in various priority areas – victim services, rule of law, procurement and supply chains, and public awareness and outreach.

- Other promising practices to combat human trafficking:

- There are other practices that could inform Canada’s future approach to combating human trafficking. For example, using the experience of survivors to guide policies, detecting cases before they reach the country and encouraging companies to make their supply chains free of human trafficking. Integrating these practices will allow the next iteration of the NAP-HT to move beyond sexual exploitation and to tackle other forms of human trafficking (e.g. forced labour).

Evaluation Findings: Performance - Government and Data Sources

Key Findings: Performance –Governance

Findings: The only governance committee that was put in place to oversee the implementation of the action plan was at the working level. Although the committee functioned well, evidence suggests a need to establish a higher-level engagement structure in the future to provide strategic guidance and direction.

- The NAP-HT had well-functioning horizontal governance at the working level:

- The NAP-HT was solely governed by a working-level Human Trafficking Taskforce (HTT) led by Public Safety Canada in partnership with other federal participating organizations. There was no senior management-level steering committee.

- The HTT was effective in serving as a focal point for federal participating organizations to share information.

- With the establishment of the NAP-HT, the HTT became the information-sharing forum for federal participating organizations to find out what others were doing.

- Federal partners interviewed acknowledged that because human trafficking is addressed by many different federal organizations, structuring the HTT as the information hub functioned well and such a role remains appropriate.

- The HTT was also effective in the monitoring and reporting of the NAP-HT implementation.

- Between 2012 and 2016, three annual progress reports were published.

- Federal partners provided updates at the HTT meetings (on average, four times a year).

- Interviewees felt that in the future, the HTT will need to evolve from being solely an information sharing forum to a platform where more collaborative efforts could be realized.

- There might be a need to establish a higher-level engagement structure:

- Some interviewees commented that although a working-level taskforce was sufficient to address operational issues, going forward, there could be benefits to have a higher level engagement structure to provide strategic guidance and direction.

Key Findings: Performance –Data Sources

Findings: There are limited reliable and accurate data sources to map out the scope and nature of human trafficking in Canada, making it difficult for policy makers to implement effective federal responses to human trafficking.

- In its 2010 report entitled: Towards the Development of a National Data Collection Framework to Measure Trafficking in Persons, Statistics Canada indicated that there was a “lack of comprehensive, reliable and comparable data.” This was found to be still the case. Some of the contributing factors according to the interviewees and the literature included:

- The lack of a centralized database:

- Available data is dispersed among individual organizations. Privacy concerns, confidentiality and protection of victim’s identity are cited as barriers to sharing data. Federal partner interviewees stated that formal data sharing mechanisms could help improve the situation.

- Under-reporting throughout the spectrum of human trafficking-related activities:

- Accurate reporting depends on the ability of law enforcement personnel and front-line service providers to recognize and identify potential human trafficking situations. In practice, this is challenging due to the hidden and covert nature of human trafficking.

- The crime is not always reported. Victims might not consider themselves as such and/or there may be a level of mistrust of authorities.

- Human trafficking-related charges are often dropped, and thus do not get recorded into the crime-related databases. This happens because law enforcement officers often find it difficult to gather sufficient evidence to prove human trafficking cases and they, therefore, charge human traffickers under alternate charges (e.g. procuring and sexual assault).

- Inconsistent definitions leading to non-comparability of data:

- There is a lack of common and consistent understanding of basic information such as the definitions for human trafficking cases, victims and traffickers among government organizations, service providers and non-governmental organizations who collect the data. Data comparability, therefore, becomes difficult.

- Part of the challenge to develop a set of standardized definitions stems from stakeholders collecting human trafficking data to serve their internal needs, each using their own information sources (e.g. service providers collect information on the people they serve).

- Official government documents generally rely on police-reported and court data as their sources.

- The lack of a centralized database:

- The evaluation attempted to assess (through an evaluation question) the extent to which gender and diversity-based perspectives (e.g. male/female, adult/children, Indigenous/non-Indigenous, Canadian-born/foreign-born) were taken into account during the implementation of the NAP-HT. However, this type of information was mostly non-existent.

- Literature review and interviewees pointed out that having accurate, reliable and ongoing data are essential tools to inform and assist policy makers in the design and implementation of the NAP-HT. In the absence of reliable data, the current state and trends of human trafficking are not accurately represented, leaving the government in a difficult position to assess the effectiveness of the federal responses to human trafficking.

Evaluation Findings: Performance - Four Pillars

(Prevention, Protection, Prosecution, Partnership)

Key Findings: Performance – Prevention

Findings: The NAP-HT contributed to increasing the awareness and understanding of human trafficking situations among federal government institutions. However, it was less clear to what extent the NAP-HT contributed to increase awareness among civil society and at-risk populations.

- The NAP-HT aimed to increase awareness and understanding of human trafficking among federal government institutions, civil society institutions, and at-risk populations.

- Through the NAP-HT, the level of awareness and understanding increased among federal government institutions. The same could not be said for the civil society institutions.

- Federal interviewees indicated that the NAP-HT gave federal organizations a framework/policy direction, improved knowledge, increased information sharing and engagement as well as collaboration among federal organizations and law enforcement.

- Federal interviewees indicated consultations conducted under the NAP-HT contributed to increasing awareness and understanding among the civil society. While civil society and provincial government interviewees indicated that the NAP-HT’s deliverables such as awareness campaigns, consultations, national, and regional forums were helpful, they were not aware that these activities were conducted as part of the NAP-HT. This suggests the need for federal organizations to better communicate the action plan and its activities among the civil society and provincial governments.

- Regarding the NAP-HT’s contribution to improving the ability of the government and civil society institutions to detect potential victims and places of human trafficking, interviewees expressed mixed views. However, some interviewees indicated that the research conducted under the NAP-HT was a good start to help these institutions understand the situation and, therefore, detect potential victims.

- Interviewees noted that improved information and knowledge-sharing as well as engagement between different levels of government and civil society institutions could increase the ability of these institutions to raise awareness and detect potential victims.

- Interviewees from civil society institutions highlighted certain challenges, such as:

- the ability of federal front-line employees to understand and recognize victims of human trafficking;

- the need to establish better relationships between law enforcement and sex trade workers, especially among Indigenous groups. Accordingly, establishing trusting relationships will make it easier for potential sex trafficking victims to come forward; and

- the insufficient data and research.

- There was no clear evidence to indicate that the NAP-HT contributed to increased awareness and understanding on the part of at-risk populations.

- The NAP-HT’s contribution to enabling at-risk populations to recognize their situation and to seek help was perceived as limited by interviewees.

- Interviewees were aware of some of the activities conducted under the prevention pillar for at-risk populations such as the I’m Not for Sale campaign, the TruckSTOP campaign and the distribution of pamphlets. Nevertheless, they also suggested that more prominent national awareness campaigns targeted to at-risk populations and more comprehensive consultations are needed.

Key Findings: Performance – Protection

Findings: The NAP-HT, to some extent, contributed to identify, protect, and support victims in their recovery.

- The NAP-HT aimed to identify, protect, and support victims in their recovery by:

- Improving services to victims of human trafficking by funding projects;

- Establishing measures to identify and protect vulnerable foreign nationals in Canada.

- While specific projects funded by the federal government were cited to be useful, the coverage of these projects was limited to only some cities and provinces.

- Since April 2013, the Department of Justice Victims Fund made available up to $500K annually to support projects that improved services to victims of human trafficking. The Fund supported 10 projects between 2012 and 2016 in four provinces: Quebec, Alberta, British Columbia, and Ontario. Provincial and civil society interviewees who received funding described these specific projects as useful for building capacity to support victims, improving services and providing tools to victims.

- Status of Women Canada also funded several projects to prevent and reduce the human trafficking of women and girls for the purposes of sexual exploitation through community planning. Three projects were funded for a total amount of $600K for a period of up to 30 months in Edmonton, Ottawa and Toronto. In 2015-16, three new additional projects were being funded to address the issue of human trafficking.

- As part of the NAP-HT, multiple measures were taken under the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFW Program) and International Mobility Program (IMP) to identify and protect vulnerable foreign national workers.

- Measures undertaken included:

- 2012: Employers who operate in the sex trade were refused access to the TFW Program;

- 2013: Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada received the authority to inspect employers who use the TFW Program and International Mobility Program to validate their compliance with requirements of these programs;

- 2014: The launch of the anonymous Tip Line and the Online Fraud Reporting Tool have improved the detection of abuse. From April 2014 to March 31, 2016, through these mechanisms, ESDC has received over 4,600 leads resulting in over 640 inspections;

- 2015: The targeted number of inspections for employers using the TFW Program increased to 25% starting in 2015-16. This target was met, increasing the number of inspections from 1,375 in 2014-15 to 3,531 in 2015-16. A similar employer-compliance framework was launched under the International Mobility Program initiating 354 employer compliance inspections in 2015-16.

- 2015: Amendments to the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (IRPA) were made to respond proportionately to non-compliance with TFWP/IMP conditions and to implement a system of varied administrative monetary penalties, bans and warning statements to replace the existing mandatory two-year ban.

- When suspected criminal activities under the TFW Program were found, ESDC referred these cases to law enforcement agencies. Since 2014, ESDC has made 268 such referrals.

- However, interviewees indicated that many vulnerable foreign national workers do not seek help due to the threat of deportation. There were cases which showed undocumented workers received departure orders soon after coming forward.

- Measures undertaken included:

- The Temporary Resident Permit (TRP), is an important mechanism to protect and support potential victims of human trafficking by providing them with temporary immigration status. Although, the TRP plays an important role in protecting victims, literature review and interviewees revealed that the TRP may be under-used for the purpose of protecting victims of human trafficking.

- In the context of human trafficking, an initial short-term TRPs can be issued to potential foreign national victims by securing their immigration status in Canada for up to 180 days when an immigration officer is able to make a preliminary assessment that an individual may be a victim of human trafficking. A longer-term or a subsequent TRP could be issued when a more complete verification of the facts provide reasonable evidence that the individual is a victim of human trafficking. Victims of human trafficking who are TRP holders have access to healthcare benefits covered by the Interim Federal Healthcare Program (IFHP) and are also eligible for an open work permit (if the TRP is issued for 180 days or more).

- TRP and IFHP were identified as important tools in providing protection and support to potential foreign national victims of human trafficking.

- Nonetheless, literature review and interviewees revealed some evidence that TRP may be under-used for the purpose of protecting victims of human trafficking. Contributing factors included the lack of knowledge of the TRP, the threat of deportation, and lengthy nature of the TRP process.

- Available statistics showed that between 2012 and 2015, IRCC issued 142 TRPs (119 to potential victims of human trafficking and 23 to their children and spouses) and issued 97 IFHP certificates. These potential victims suffered sexual and/or labour exploitation, or other unspecified exploitation.

- Overall, interviewees suggested some best practices that would benefit the NAP-HT under this pillar:

- A dedicated national hotline to assist victims to access services;

- Greater engagement from a wider spectrum of stakeholders in society such as working further with the tourism industry, medical professionals, and frontline service providers to identify signs of human trafficking.

Key Findings: Performance – Prosecution

Findings: Through the NAP-HT, some work was undertaken to strengthen the capability of law enforcement agencies to investigate and prosecute human trafficking crimes. However, there is very limited evidence to indicate that the NAP-HT contributed to enhance intelligence collection, coordination, and collaboration and to disrupt crime groups.

- The NAP-HT’s aimed to strengthen the capability of law enforcement agencies to investigate and prosecute crimes of human trafficking by:

- establishing a dedicated integrated enforcement team to undertake proactive human trafficking investigations;

- providing human trafficking training and education for prosecutors and law enforcement;

- enhancing intelligence collection, coordination, and collaboration.

- The RCMP Immigration and Passport Unit in Quebec actively investigated human trafficking files and worked closely with Canadian and American partners. The Immigration and Passport Unit was identified as the dedicated Human Trafficking Enforcement Team in December 2013 while remaining responsible for their immigration and passport duties and responsibilities.

- The Human Trafficking Enforcement Team was an RCMP Federal Policing Team which was responsible for international human trafficking investigations in Quebec and continued until the end of the NAP-HT.

- Most law enforcement personnel interviewed indicated that they collaborated with the RCMP on human trafficking cases within their jurisdictions; however, they did not have interactions with the dedicated Human Trafficking Enforcement Team in Quebec. Most of the interactions of the dedicated Human Trafficking Enforcement Team were with law enforcement in Quebec. This may suggest the need to better communicate the expanded mandate of the dedicated Human Trafficking Enforcement Team.

- Launched in 2005, the RCMP Human Trafficking National Coordination Centre (HTNCC) provides support and coordination functions to investigators. During the evaluation period, the HTNCC delivered training and awareness sessions to various audiences including law enforcement officials, prosecutors and government employees. It also developed knowledge tools (e.g. brochures, newsletters, toolkits, threat assessments).

- In 2015, the Department of Justice published the “Handbook for Criminal Justice Practitioners on Trafficking in Persons” to provide guidance to law enforcement and prosecutors in the investigation and prosecution of human trafficking cases.

- There is very limited evidence to indicate that the NAP-HT contributed to enhanced intelligence collection, coordination, and collaboration:

- There is no national mechanism or requirement to collect and share intelligence data across provinces. The lack of national intelligence data makes it challenging to have coordinated law enforcement responses.

- According to interviewees: the NAP-HT did not enhance the ability of law enforcement agencies to share intelligence and the HTNCC did not have the capacity to support the coordination of human trafficking investigations:

- Information collected indicated that although the HTNCC staff were viewed as skilled and knowledgeable, the Centre has been operating at less than full capacity at the RCMP headquarters in Ottawa and in the regions. Interviewees further noted the need to have a sufficient number of HTNCC regional coordinators in place to facilitate information and intelligence sharing across provincial boundaries.

- The NAP-HT had a limited contribution to disrupt crime groups.

- Interviewees indicated that the NAP-HT had a limited contribution to disrupting crime groups and others involved in human trafficking. They mentioned that the number of charges, prosecutions, and convictions remained low.

- From 2012 to 2016 there were 307 human trafficking cases (of which 291 were related to domestic trafficking for sexual exploitation) and there were 45 human trafficking specific or related convictions.

- Based on literature review and information collected from interviewees, there are certain external factors that limit the ability of the federal law enforcement to investigate and prosecute human trafficking crimes. For example:

- The majority of human trafficking criminal offences are investigated and prosecuted at the municipal and provincial levels. At the federal level, these cases are prosecuted by the Attorney General of Canada only when the offences involve crossing international borders (i.e. under Section 118 of IRPA) or are committed in one of the three Canadian Territories.

- It is difficult to gather sufficient evidence to prosecute traffickers. Victims are reluctant to testify for fear of reprisals by the traffickers. Consequently, human trafficking charges are often withdrawn in favour of other charges. While the NAP-HT could have played a bigger role to support victims to come forward, there are other stakeholders who need to be involved (e.g. front-line service providers, etc.).

Key Findings: Performance – Partnership

Findings: There is room for the NAP-HT to strengthen the partnership between the federal government and the provinces and with non-governmental organizations. Partnership efforts through the NAP-HT did not translate into facilitating policy development and capacity building abroad.

- The NAP-HT aimed to strengthen the partnerships of the federal government with its domestic and international stakeholders, in order to enhance knowledge sharing, facilitate policy development, and build capacity abroad.

- Despite the work performed through the NAP-HT to forge stronger partnerships, some interviewees noted that there is room to improve the partnership between the federal government and the provinces and non-governmental organizations.

- Regarding the opportunities for knowledge exchange among stakeholders, the NAP-HT made numerous efforts to enhance national engagement. However, interviewees from the provincial governments and non-governmental organizations felt that more could be done.

- Multiple efforts were made to enhance national engagement:

- Four national stakeholder consultations (2012 to 2016);

- Five regional roundtables (2012);

- Nine teleconference calls between the federal and provincial governments (2013 to 2016);

- Ten issues of Canada’s Anti-Human Trafficking Newsletters were published (2012 to 2016).

- Multiple efforts were made to enhance national engagement:

- Canada shared the work of its Human Trafficking Taskforce, National Action Plan, and best practices during meetings at the international level (e.g. UN forums on crime prevention and criminal justice in 2014 and 2015).

- While interviewees from the provincial governments found the opportunities for engagement and information sharing useful, they noted that these occasions had been more sporadic and less frequent in recent years.

- Most interviewees from non-governmental organizations commented that they did not think that the NAP-HT contributed to enhanced engagement and collaboration between the federal government and the civil society.

- Interviewees indicated that the NAP-HT had a limited impact to facilitate policy development.

- Some federal partner interviewees noted that although the NAP-HT provided opportunities to initiate policy discussions with each other, these discussions did not lead to further policy development in the area of human trafficking.

- In addition, interviewees from non-governmental organizations felt that they were not adequately consulted in the implementation of the NAP-HT and that they did not have the opportunity to inform policy development.

- Although Canada has performed activities to strengthen capacity building in other countries, the NAP-HT was not the driver of these efforts.

- Federal partner interviewees indicated that Canada’s international capacity building efforts were mainly driven by Global Affairs Canada’s Peace and Stabilization Operations and the Anti-Crime Capacity Building Programs, rather than by the NAP-HT.

Evaluation Findings: Performance - Costing

Findings: The majority of federal organizations were unable to track the NAP-HT specific expenditures. They attributed this to the absence of dedicated funding. Given this, the evaluation was unable to fully assess the actual cost of the NAP-HT implementation.

- The majority of partner organizations were unable to track the NAP-HT expenditures:

- The NAP-HT indicated that the Government would be investing over $6M annually. Subsequently, six of the nine key partner organizations committed to spend $7.3M in total (through reallocation of existing internal resources), for the first year 2012-13. No funding commitments were made by the remaining three organizations (Annex C).

- To estimate the overall cost of implementing the NAP-HT related activities, the evaluation team requested partner organizations to provide an estimate of their departmental spending on relevant activities over the evaluation timeframe.

- Out of those six organizations with initial funding commitments, two provided spending information that was aligned with their initial commitments; three organizations provided spending information that was lower than their initial commitments; and one organization did not provide any cost estimate.

- These organizations explained that it was difficult to fully track the costs of the implementation because they did not receive any new, dedicated funding, which meant that they carried out NAP-HT related activities as part of their regular operations with their existing internal resources. Therefore, there was no dedicated coding in the financial systems to capture the cost of anti-human trafficking related activities.

- In addition, some partner organizations indicated that the NAP-HT was launched one year after the start of the Government of Canada’s Deficit Reduction Action Plan (DRAP), which had an impact on their ability to fully support the implementation of the NAP-HT.

- Partner organizations interpreted the departmental funding commitment differently:

- There also seemed to be varying interpretations of the Government’s funding commitment by different organizations. While some partners thought that the departmental funding commitment was an annual amount committed for the duration of the NAP-HT, some organizations interpreted it to be only for the first year of the implementation. There were yet others who argued that the departmental funding amount represented planned spending for existing programs that had anti-human trafficking component Our review of the relevant text in the Action Plan confirmed that the document only specified departmental funding commitments for the year 2012-13, leaving room for interpretation as to what was expected for the following years.

- The absence of dedicated funding was described by some interviewees to have created both opportunities and challenges:

- Although some organizations stated that the absence of dedicated funding allowed them to become more innovative and to focus on awareness and training, others viewed the absence of dedicated funding limited the ability of organizations to achieve the NAP-HT outcomes.

Conclusions

- The NAP-HT filled a need for coordinated national efforts to address human trafficking across Canada. Continued efforts are required that span all levels of government, private sector, Indigenous communities and civil society as human trafficking persists. NAP-HT working level governance was effective at bringing together federal partners, however a higher-level engagement structure may be needed to provide oversight and strategic direction.

- In terms of the NAP-HT’s overall performance, there was progress made to raise awareness and to provide training for federal, provincial, and territorial government officials and criminal justice personnel. As well, there were additional measures introduced to identify and protect foreign nationals and funding was made available for projects to support victims of human trafficking.

- The NAP-HT had a limited contribution to the investigation and prosecution of human trafficking crimes. There are external factors (e.g. jurisdictional constraint, difficulty to collect sufficient evidence for prosecution) that limit the ability of federal law enforcement agencies to conduct such investigations and prosecutions. Moreover, with the exception of border-related cases, the majority of the offences are investigated and prosecuted at the municipal and provincial levels.

- Potential victims and Canadian citizens do not have access to a dedicated mechanism for accessing services or reporting suspected cases of human trafficking. A mechanism, such as a national hotline, would enhance accessibility for potential victims to seek support and Canadian citizens to report instances of human trafficking. Furthermore, such a mechanism could potentially help collect data to better understand the scope and nature of human trafficking issues, as there is a lack of consistent national data.

- The majority of participating organizations were unable to track the NAP-HT expenditures reportedly because they did not receive any new dedicated funding, making it difficult to fully assess the actual cost of the NAP-HT.

Recommendations

In collaboration with the participating organizations, the ADM of the Community Safety and Countering Crime Branch of Public Safety Canada should consider to:

- Developing and implementing a coordinated approach to address the continued need to combat human trafficking taking into account the evaluation findings;

- Enhancing Canada’s response to combat human trafficking by forging closer partnerships with other levels of government, Indigenous communities, civil society, the private sector as well as bilateral and multilateral partners;

- Implementing a mechanism to connect victims with access to dedicated services and facilitate reporting of human trafficking;

- Improving capacity to collect national data on human trafficking; and

- Putting in place a mechanism to collect relevant and reliable performance information, including information on program expenditures to support program management and accountability.

Management Response and Action Plan

The Programs Directorate has reviewed the report and the recommendations and is in agreement with the findings. The evaluation recommendations will inform the development of a renewed national strategy to combat human trafficking and a performance measurement strategy. Programs will take the opportunity to engage Other Government Departments (OGDs), the Provinces and Territories (P/Ts) and other non-government stakeholders to enhance collaboration at the national level and explore options to improve data collection.

| Action planned | Deliverable(s) | Planned Completion Date |

|---|---|---|

| Engage OGDs to pursue the policy renewal process toward a new national strategy to combat human trafficking integrating the evaluation findings. | Policy options presented in collaboration with HTT partners. | April 2018 |

| a) Engage OGDs to review the existing Terms for Reference for the Human Trafficking Taskforce and with a view to: Consider alternative governance options to enhance the effectiveness of Canada’s response to combat human trafficking. b)Identify options to enhance collaboration within the federal government, with P/Ts, First Nations and non-government stakeholders |

a) New/updated Terms of Reference. b)Options presented in collaboration with HTT partners. |

May 2018 |

| Examine the feasibility and effectiveness of a national hotline and referral mechanism for victims and potential victims of human trafficking. | Table options and recommended approaches to enable/improve data collection and support the creation of a national referral mechanism. | January 2018 |

| Engage OGDs, P/Ts and non-governmental stakeholders to explore options to improve data collection. | Options presented to improve data collection. | January 2018 |

Develop a Program Information Profile to reflect the priorities of a renewed national strategy by:

|

Seek approval for, and implement the Program Information Profile. Creation of HTT Program Information Profile sub-committee. |

March 2018 |

Annexes

Annex A: Evaluation Questions

Relevance

- To what extent is the NAP-HT still relevant to meet evolving needs?

- To what extent is the NAP-HT aligned with federal government priorities?

- How does Canada compare to the other countries in relation to their responses to combat human trafficking? For example, have other countries implemented national action plans and if so, how are these plans being funded?

Performance

- To what extent have there been effective horizontal governance and coordination among the federal participating organizations?

- To what extent are there reliable and accurate data sources to map out the scope and nature of human trafficking? What has been the impact on the NAP-HT outcome achievement?

- (Prevention) To what extent has the NAP-HT contributed to the improvement in the ability of at-risk populations to recognize their situation and seek support?

- (Prevention) To what extent has the NAP-HT contributed to the improved ability of institutions to detect potential victims/places of human trafficking?

- (Protection) To what extent has the NAP-HT contributed to victims being identified, protected and supported in their recovery?

- (Prosecution) To what extent has the NAP-HT contributed to organized crime groups and other persons involved in human trafficking being disrupted?

- (Partnership) To what extent has the NAP-HT contributed to partnerships being strengthened domestically and internationally to facilitate policy development, improvement of knowledge sharing and capacity-building abroad?

- What is the full estimated cost of each partner's NAP-HT activities and how have these costs differed from the initial funding commitment?

Annex B: Logic Model

Image description

The Logic Model works as a communication tool that summarizes the key elements of the program, explains the rationale behind program activities, and clarifies all intended outcomes.

The activities under the prevention and protection pillars include:

- Develop and support HT awareness campaigns/materials

- Provide funding to projects that improve services to victims of HT

- Develop diagnostic tools to help identify the populations and places at risk of HT

- Provide awareness training and education to frontline service providers, law enforcement officials, prosecutors and the judiciary

- Enhance regulatory & administrative procedures and instruments to protect victims of HT

The activities under the prosecution and partnership pillars include

- Establish dedicated integrated investigative team

- Provide legal advice and conduct prosecutions

- Share best practices, data and intelligence

- Establish partnerships at all levels of government within Canada and with international organizations and foreign governments

The outputs under the prevention pillar are:

- Training programs

- Diagnostic tools

- Awareness campaigns/materials

- Knowledge Products

The outputs under the protection pillar are:

- Training programs

- Services for victims of HT

- Enhancements to program policy, regulations and administrative arrangements

The outputs under the prosecution pillar are:

- Training and Education Programs

- Dedicated Integrated Investigative Team

- Legal advice and prosecutions

- Operational Tools

- Partnerships

The outputs under the partnership pillar are

- Partnerships with domestic and international organizations and foreign governments Knowledge sharing Capacity-building initiatives abroad

The immediate outcome under the prevention pillar is:

- Increased awareness and understanding of HT on the part of at-risk populations, institutions and civil society

The immediate outcome under the protection pillar is:

- Increased access to services by victims and populations at risk of human trafficking

The immediate outcome under the prosecution pillar is:

- Strengthened capabilities to investigate and prosecute crimes of human trafficking

The immediate outcome under the partnership pillar is:

- Enhanced engagement, collaboration and information sharing with civil society & all levels of government in Canada & abroad

The intermediate outcomes under the prevention pillar are:

- Improved ability of at risk populations to recognize their situation and to seek help Improved ability of institutions to detect potential victims and places of HT

The intermediate outcome under the protection pillar is:

- Victims of HT are identified, protected and supported in their recovery

The intermediate outcome under the prosecution pillar is:

- Organized crime groups and other criminals involved in HT are disrupted

The intermediate outcome under the partnership pillar is:

- A coordinated and strengthened approach to combatting HT in Canada and internationally

The ultimate outcome is:

- Prevent Human Trafficking, Protect the Most Vulnerable, Identify Victims and Prosecute Perpetrators

Annex C: Initial funding commitment by Government of Canada

| Effort or Activity (Lead Organization) | Government of Canada Investment 2012/13 | |

|---|---|---|

| Dedicated Enforcement Team (RCMP and CBSA) | $2,030,000 | |

| Human Trafficking National Coordination Centre (RCMP) | $1,300,000 | |

| Regional Coordination and Awareness (RCMP) | $1,600,000 | |

| Border Service Officer Training/Awareness (CBSA) | $445,000 | |

| Training, Legislative Implementation, and Policy Development (JUS) | $140,000 | |

| Enhanced Victim Services (JUS) | Up to $500,000* | |

| Temporary Foreign Worker Program (ESDC) | $140,000 | |

| Anti-Crime Capacity Building Program (GAC) | $96,000 | |

| Global Peace and Security Fund (GAC) | $1,200,000 | |

| Stakeholder Consultation and Coordination (PS) | $200,000 | |

| Awareness and Research (PS) | $155,000 | |

| * Beginning in 2013/14 | ||

- Date modified: