2010-2011 Evaluation of the Integrated Proceeds of Crime Initiative - Final Report

Table of contents

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Profile

- 3. About the Evaluation

- 4. Findings

- 4.1 Relevance

- 4.1.1 Continued Need for Program

- 4.1.1.1 Is there a continued need for the IPOC Initiative?

- 4.1.1.2 To what extent are the objectives of the IPOC Initiative (i.e. targeting their illicit proceeds and assets) still relevant to fight organized criminals and crime groups?

- 4.1.1.3 To what extent are the Initiative theory and design appropriate in addressing ongoing needs?

- 4.1.2 Alignment with Federal Government Priorities

- 4.1.3 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

- 4.1.1 Continued Need for Program

- 4.2 Performance

- 4.2.1 Achievement of Expected Outcomes

- 4.2.1.1 To what extent have the IPOC Initiative's expected outcomes been achieved?

- 4.2.1.2 To what extent is the IPOC Initiative organized appropriately to meet its objectives?

- 4.2.1.3 What have been the challenges, if any, to the IPOC Initiative and how have these challenges been addressed or overcome?

- 4.2.1.4 Are practices, systems, and mechanisms in place to ensure proper monitoring of effectiveness and outcomes/results?

- 4.2.1.5 Has an efficient network been put in place?

- 4.2.1.6 Have public communications been integrated in the IPOC Initiative strategy to increase knowledge of POC and ML activities, issues and investigative tools?

- 4.2.1.7 Has the Initiative had any unintended impacts (positive or negative)?

- 4.2.2 Performance--Efficiency and Economy

- 4.2.1 Achievement of Expected Outcomes

- 4.1 Relevance

- 5. Conclusions

- 6. Recommendations

- 7. Management Response and Action Plan

- Appendix A: References

- Appendix B: Inventory of Previous IPOC Evaluation

- Appendix C: Evaluation Question Matrix

Executive Summary

What we examined

The evaluation of the Integrated Proceeds of Crime Initiative (henceforth referred to as the "Initiative"), which covers the period 2005-2006 to 2009-2010, was conducted by Public Safety Canada, in consultation with the Initiative's Evaluation Advisory Committee, which included representatives of the Initiative and of the evaluation units of the federal departments and agencies involved. This Evaluation was conducted in conformity with the Treasury Board's Policy on Evaluation. Its objective is to provide an evidence-based, neutral assessment of the relevance and performance of the Initiative.

The inter-departmental Initiative brings together the following federal organizations: the Canada Border Services Agency; the Canada Revenue Agency; the Public Prosecution Service of Canada; Public Safety Canada; Public Works and Government Services Canada - Forensic Accounting Management Group; and, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

The Initiative contributes to the disruption, dismantling and incapacitation of organized criminals and crime groups by targeting their illicit proceeds and assets. Dedicated, integrated resources from six federal partners have joined together in the Initiative to facilitate investigations, to share information and to turn that information into intelligence that can be used by front-line investigators and ultimately by prosecutors. Over time, the Initiative's units have also included resources from provincial and municipal police forces that allowed for joint operations that contributed to the disruption and dismantling of organized criminal groups.

The Initiative is chaired by Public Safety Canada. The Initiative's total funding for the period 2005-2006 to 2009-2010 was $116.5 million.

The evaluation methodology included the conduct of a document and literature review, key representative interviews and group interviews, database review and analysis, and case studies.

Why it's important

Organized crime is considered as one of the major threats to national security, impeding the social, economic, political and cultural development of societies worldwide. It is a multi-faceted phenomenon and has manifested itself in different activities, among them: drug trafficking, trafficking in human beings, trafficking in firearms, smuggling of migrants, money laundering, proceeds of crime, etc. In particular, drug trafficking is one of the main activities of organized crime groups, generating enormous profits.

In Canada there were approximately 750 criminal groups identified in 2009Note 1. As stated in a Public Report on Actions under the National Agenda to Combat Organized CrimeNote 2, "since organized criminals seek out countries known to have less effective regulatory and enforcement systems, any jurisdiction that does not have adequate defences is at risk and may cause risk to other countries. As perhaps never before, the policies and enforcement capabilities of any one country have direct consequences globally". The Initiative is one of the tools Canada gave itself to fight organized criminals and criminal groups. The Initiative focuses on identifying, assessing, seizing, restraining and dealing with the forfeiture of illicit wealth accumulated through criminal activities.

Targeting proceeds of crime has been put forward by many specialists as one of the most effective approaches in the fight against organized crime. In this regard, the Canadian government, through its National Agenda to Combat Organized Crime, is committed to working with provinces, municipalities, and international partners to protect its citizens and the country's economic infrastructure against organized crime. Proceeds of crime investigations, prosecutions, seizures and forfeitures are key tools for the Government in its fight against organized crime.

What we found

Relevance

- The underlying objectives of the Initiative remain relevant today. They respond to Canada's national and international commitments against organized crime. 'Proceeds of crime' is identified as a priority by the Government of Canada and a key component of the National Agenda to Combat Organized Crime.

- The literature reviewed overwhelmingly supports the need for continuing efforts to combat organized crime by targeting proceeds of crime. This position is supported by all of the partners interviewed during this evaluation. Viewed in this context and the current environment, the Initiative remains a relevant key component in Canada's broader anti-crime strategy at the national and international levels.

- The initial theory and design of the Initiative was focused around the Criminal Code and other related federal legislation. In recent years, the expansion of civil forfeiture laws and their increased use to seize and forfeit illegal assets has influenced the initial theory and design of the Initiative, since civil forfeiture was not in place at the time of the Initiative's inception. In order to remain relevant and effective, the Initiative must constantly adapt to these new realities, by redesigning its operations to make maximum use of these new tools in the right circumstances.

Performance

- The Initiative has had an impact on organized crime and crime groups. This impact is evident from cases addressed by the Initiative over the evaluation period, especially major cases such as Opération Colisée, where a joint operation combining efforts from the Initiative's partners and provincial and municipal police forces, succeeded in dismantling the Montréal-based Italian mafia. Statistics collected during the evaluation also confirm that the Initiative was effective at disrupting organized crime through seizures, forfeitures and convictions.

- While the Initiative is having an impact, the findings from the evaluation team suggest that it is not as efficient or effective as it could be. Through the course of this evaluation, the following challenges faced by the Initiative were identified: funding, turnover, training, governance, monitoring, communication, legal and relationships challenges.

- To meet its objectives in an efficient way, the Initiative requires close communications and collaboration among its partners. Indeed, the original concept of the Initiative focused on integration as a key feature of the Initiative. The evidence obtained through the course of the evaluation suggests that this core feature of the Initiative has faded somewhat over time to the detriment of its operation.

- The Initiative's operations have been adversely impacted by several human resource factors, including: some partners physically leaving the units (organizations are no longer co-located), staff turnover, vacant positions, recruitment difficulties, lack of seasoned personnel and insufficient training. These human resources factors need to be addressed so as to ensure that the Initiative is restored to a fully functional Initiative.

- Consistency and uniformity of performance data can be seen as a necessary hallmark of any integrated operation. However, an integrated monitoring system was not in place at the time of this evaluation. Furthermore, all of the Initiative's partners have their own reporting systems and tools, and no common standard exists among them. Steps need to be taken by the Initiative's partners to better monitor its performance using a consistent set of performance metrics.

- In summary, the lack of an overall strategy and business plan, communication and relationships among partners, human resources, integration, lack of performance indicators and a common monitoring system, etc. are factors contributing to less than optimal performance.

Recommendations

Three recommendations emerge from the findings of the 2010-2011 evaluation of the Initiative.

It is recommended that under the leadership of Public Safety Canada, the Initiative's Advisory Committee (with the approval of the Integrated Proceeds of Crime Initiative's Senior Governance Committee):

- Review the theory and design of the Initiative, including its objectives and logic model, based on the internal/external changes presented in section 4.1.1.1 of this evaluation (by March 31, 2012).

- Develop a five-year comprehensive strategy, including a business and communication plan, which would also consider key challenges pertaining to relations between partners, funding, monitoring and reporting, and which would take into account the modifications made to the Initiative's theory and design.

In addition, it is recommended that: - The Royal Canadian Mounted Police continue to expend necessary efforts to address and resolve current and anticipated recruitment, retention and training issues specific to the Initiative.

Management Response and Action Plan

This evaluation report has been reviewed and approved by deputy heads of all the Initiative partner organizations. In addition to providing management action plans for partners directly affected by the evaluation's recommendations, all partners were provided the opportunity for responding to this report, and for participating in the evaluation of the Initiative.

All of the Initiative's partners agree with the recommendations of the report, support the management responses and action plans and commit to working together to implement these plans. Under the leadership of the Initiative's Senior Governance Committee, through their representatives on the Initiative's Advisory Committee, the partners will: ensure the periodic review the Initiative's objectives, outcomes and expectations; review the theory and design of the Initiative, including its logic model, based on internal and external changes; and, develop a five-year comprehensive strategy, including a business and communication plan.

Specifically:

Canada Border Services Agency

Canada Border Services Agency accepts and supports the evaluation and its recommendations. The Agency concurs with the main findings of the report, and agrees that the underlying objectives of the Initiative remain relevant today in responding to Canada's national and international commitments with respect to organized crime and terrorism. To be effective, the Initiative must adapt to a dynamic environment in which the tactics employed by organized crime - and the Government's response to these tactics - are constantly evolving. The Agency will collaborate with the Initiative's partners to review the theory and design of the Initiative, and to develop a comprehensive strategy for moving the Initiative forward.

Canada Revenue Agency

Canada Revenue Agency accepts and supports the evaluation and its recommendations. The Agency approves the proposed management action plan pertaining to the Advisory Committee. The Agency will support their implementation through its continued participation on the Initiative's Senior Governance Committee as well as the Initiative's Advisory Committee.

With respect to the performance data from the Canada Revenue Agency Special Enforcement Program, beginning in 2011, the Agency will start tracking the federal taxes recovered and provide this information to the Initiative's partners.

Public Prosecution Service of Canada

Public Prosecution Service of Canada accepts and supports the evaluation and its recommendations. Public Prosecution Service of Canada will support their implementation through its continued participation on the Initiative's Senior Governance Committee as well as the Initiative's Advisory Committee.

In addition, Public Prosecution Service of Canada will work with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to renew the 1997 Memorandum of Understanding between the two organizations in order to clarify their respective roles and responsibilities under the Initiative, given the internal and external changes identified by the evaluation.

Public Safety Canada

Public Safety Canada accepts and fully supports the evaluation and its recommendations. As part of its ongoing commitment to the Initiative, Public Safety Canada will continue to work with its federal partners to strengthen the Initiative.

- Public Safety Canada will work with the Initiative's Advisory Committee and the Initiative's Senior Governance Committee to review the theory and design of the Initiative, including its objectives and logic model, based on internal and external changes (by March 31, 2012).

- Public Safety Canada will work with the Initiative's Advisory Committee and the Initiative's Senior Governance Committee to develop a five-year comprehensive strategy, including a business and communication plan, which would also consider key challenges pertaining to relations between partners, funding, monitoring and reporting, and which would take into account the modifications made to the Initiative's theory and design.

Public Works and Government Services Canada - Forensic Accounting Management Group

Public Works and Government Services Canada - Forensic Accounting Management Group accepts and supports the evaluation and its recommendations. Public Works and Government Services Canada - Forensic Accounting Management Group will support the implementation of the management response and action plan that will be approved by the appropriate Initiative's governance committee(s).

Royal Canadian Mounted Police

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police accepts and supports the evaluation and its recommendations. It will continue to be an active participant on the Initiative's Advisory Committee as well as the Initiative's Senior Governance Committee.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police has and will continue to address recruitment, retention and training. It will continue to introduce online training modules to complement the initial module rolled out in January 2011, and to offer training to the Initiative's resources and partners through a dedicated, contracted subject matter expert. Regarding performance data and statistics, to accurately reflect investigational activities, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police will proceed with monitoring the implementation of the improved reporting system introduced in January 2010.

1. Introduction

This report presents the findings of the 2010-2011 Evaluation of the Integrated Proceeds of Crime Initiative (henceforth referred to as the "Initiative" or "IPOC"). This evaluation which covers the period 2005-2006 to 2009-2010 was conducted by Public Safety Canada (PS).

Evaluation assesses the extent to which a program, policy or initiative addresses a demonstrable need, is appropriate to the federal government, and is responsive to the needs of Canadians. It also studies the extent to which effectiveness, efficiency and economy have been achieved.

IPOC is an inter-departmental Initiative that brings together the following federal organizations:

- the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA);

- the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA);

- the Public Prosecution Service of Canada (PPSC);

- Public Safety Canada (PS);

- Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC) - Forensic Accounting Management Group (FAMG); and

- the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).

This evaluation respects the Treasury Board requirements to provide an evidence-based, neutral assessment of the relevance and performance of the Initiative, as articulated in its renewed Policy on Evaluation (2009).

2. Profile

2.1 IPOC Background

The IPOC Initiative contributes to the disruption, dismantling and incapacitation of organized criminals and crime groups by targeting their illicit proceeds and assets. The Criminal Code defines proceeds of crime as follow:

"Proceeds of crime means any property, benefit or advantage, within or outside Canada, obtained or derived directly or indirectly as a result of (a) the commission in Canada of a designated offence, or (b) an act or omission anywhere that, if it had occurred in Canada, would have constituted a designated offence"Note 3.

The Initiative builds on the 1992 pilot of the Integrated Anti-Drug Profiteering initiative (with three units in Montréal, Toronto and Vancouver), funded through the renewed Canada Drug Strategy. In 1996-1997, 13 IPOC units were created across Canada; this number was reduced to 12 units in 2003. In addition, the RCMP has put in place four smaller satellite units and two Proceeds of Crime (POC) units (see Tables 2, 3 and 4 for location, co-located partners and full-time employees (FTEs) for each unit).

The Initiative was designed as an innovative model of integrated law enforcement, based on the premise that removing proceeds of crime from well-organized and funded individuals or groups should reduce their economic power and influence, their ability to mount large-scale criminal enterprises, and the profit incentive to engage in criminal activities.

The Government of Canada is committed to working with its domestic and international partners to protect Canadians from the impacts of organized crime and ensure they feel safe in their communities. Proceeds of crime investigations and prosecutions are considered key tools in the Government of Canada's overall effort to combat organized crime.

The Initiative is also linked to, and works in collaboration with other organized crime initiatives, such as the Measures to Combat Organized Crime, the National Anti-Drug Strategy, the Anti-Money Laundering/Anti-Terrorist Financing Regime (AML/ATF Regime - formerly the National Initiative to Combat Money Laundering), the Public Safety and Anti-Terrorism Initiative and, most recently, the Strategy for Enhanced Protection of Canada's Capital Markets.

2.1.1 IPOC Objectives

IPOC objectives areNote 4:

- Reducing the capacity of, and increasing the costs to, targeted organized criminals and crime groups through the removal of their assets;

- Reducing the capacity of, and increasing the cost to, targeted organized criminals and crime groups through the prosecution of organized crime figures;

- Making proceeds of crime investigations more intensified, efficient and effective;

- Making prosecutions more intense, efficient and effective; and

- Increasing knowledge and understanding of proceeds of crime issues and tools.

From the objectives, the RCMP has developed the following mandate statement:

"To be intelligence led while maximizing the integrated approach in order to identify, seize, restrain, and forfeit illicit and unreported wealth accumulated by the highest level of organized criminals and crime groups identified by Divisional, Provincial and National priorities, thereby removing the financial incentive for engaging in criminal activities"Note 5.

2.1.2 Legislation - Criminal Code, Acts and Regulations

Since 1996, several legislative changes have been introduced to target the proceeds of crime. As of 2010, the provisions of the Criminal Code on Proceeds of Crime provide most of the legislative supportto take illicit wealth away from criminals. Other federal statutes, such as the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act and the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act also support enforcement objectivesNote 6.

The following is a list of the main legislation that supports the IPOC:

- Criminal Code, Part XII.2 - Proceeds of Crime

- Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act [2000, c. 17] and its regulations

- Controlled Drugs and Substances Act [1996, c. 19]

- Seized Property Management Act [1993, c. 37]

- Canada Evidence Act [1985, c. C-5]

- Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Act [1985, c. 30]

In addition to the federal legislation, eight provinces have adopted civil forfeiture legislation since 2001, and a Bill is before the Yukon Legislative Assembly. This legislation allows the provinces the judicial transfer of title to proceeds and instruments of unlawful activity through civil proceedingsNote 7. Table 1 presents the civil forfeiture legislation for each province.

| Provinces | Legislations | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Ontario | Civil Remedies Act | 2001 |

| British Columbia | Civil Forfeiture Act | 2005 |

| Nova Scotia | Civil Forfeiture Act | 2007 |

| Quebec | Loi sur la confiscation, l'administration et l'affectation des produits et instruments d'activités illégales An Act respecting the forfeiture, administration and appropriation of proceeds and instruments of unlawful activity |

2007 |

| Manitoba | The Criminal Property Forfeiture Act | 2008 |

| Saskatchewan | The Seizure of Criminal Property Act | 2008 |

| Alberta | Victims Restitution and Compensation Payment Act | 2008 |

| New Brunswick | Civil Forfeiture Act Loi sur la confiscation civile |

2010 |

| Yukon | Bill 82 - Civil Forfeiture Act | TBD |

2.1.3 Logic Model

A logic model is an essential tool in conducting an evaluation. It is a visual representation that links a program's activities, outputs and outcomes, provides a systematic and visual method of illustrating the program theory and shows the logic of how a program, policy or initiative is expected to achieve its objectives. It also provides the basis for developing the performance measurement and evaluation strategies.

The logic model for the Initiative is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1 - IPOC Logic Model

Image Description

A series of arrows point the sequential direction of the expected causal relationship from the top of the model starting with the initial "activities". The directional flow, using arrows, is depicted as downwards via "outputs", "immediate outcomes", "intermediate outcomes", and, finally, the box of "ultimate outcomes".

The "Training/outreach" activity leads to the following outputs:

- POC training sessions

- Domestic/international support/expert witness

These outputs in turn lead to the following immediate outcomes

- Increased knowledge of POC and ML activities, issues and investigative tools

- Enhanced domestic/international enforcement cooperation

The "Investigation/assistance" activity leads to the following outputs:

- Referrals to other enforcement agencies (national/international)

- POC/ML seizures, charges

These outputs in turn lead to the following immediate outcomes:

- Increased opportunities for municipal/provincial/national/international enforcement

- Removal of illicit and unreported wealth of targeted criminals and crime groups

The immediate outcomes all lead to the following intermediate outcomes:

- To contribute to the disruption, dismantling and deterrence of organized criminals and crime groups

The intermediate outcomes lead to the following ultimate outcomes:

To contribute to the Government of Canada's efforts to reduce the threat and impact of organized crime in Canadian communities, protect the integrity of the Canadian economy and support the "Safe and Secure Canada" outcome

2.1.4 Business Process

The Business Process illustrated in Figure 2 outlines the various stages and groups involved in investigating and prosecuting proceeds of crimeNote 8:

Figure 2 - IPOC Business Process

Image Description

The figure describes the resources and activities related to the IPOC business process using boxes and arrows that follow the process from top to bottom.

Stakeholders and their responsibilities are described below (the underlined phrases represent the boxes).

Organized Crime Group

- "Crime committed" (where crime has potential for proceeds involving Criminal Code Offences, Drugs, Customs, Organized Crime, Terrorism)

Polices Agencies: federal/provincial/municipal/international and Canada Border Services

- The crime committed leads to a "police investigation"

- Cross Border Currency

- FINTRAC

IPOC Units and RCMP/Other Police Agencies, DOJ, CRA, CBSA, PWGSC (FAMG, SPDM)

- Case referred if proceeds possible or likely – continuing cooperative investigation

- "Case referred to IPOC if proceeds seen to be involved" (after the police investigation, Cross border Currency and FINTRAC) and leads to "CRA tax prosecution and/or civil audit action" (case referred from IPOC if potential for income tax evasion)

- "IPOC consultation and investigation" leads to "assets seized, restrained as POC" and the "assets are maintained pending court decision"

Federal or Provincial Prosecution Services

- IPOC consultation and investigation leads to "prosecution of substantive cases" (after police investigation) and "prosecution of proceeds" (also includes prosecution under Income Tax Act and/or Excise Tax Act for GST)

Court

- "Court process and decision" (after prosecution of substantive cases and prosecution of proceeds) leads to "sentencing" which leads to "assets declared forfeit

- Cases can also be brought before provincial courts, depending on the nature of the case

- "Civil appeal before Tax Court" and "Criminal case" (after CRA tax prosecution and/or civil audit action)

SPDM Asset Disposal

- "Disposal of assets" (following assets maintained pending court decision and assets declared forfeit)

2.2 IPOC Partners and Service Providers

Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA)

CBSA provides expertise, intelligence and information in support of IPOC investigations. The Agency collects, evaluates, analyses and disseminates intelligence on actual and suspected proceeds of crime violations that impact the Customs enforcement mandate. CBSA officers assist the units either on a part-time basis or by way of a liaison officer.

Canada Revenue Agency (CRA)

CRA conducts joint tax and proceeds of crime investigations within the IPOC units and assists with the identification and timely referral to CRA of cases offering tax re-assessment potential. CRA is not funded by the Initiative.

Public Prosecution Service of Canada (PPSC)

The PPSC is responsible for prosecuting proceeds of crime offences and for providing legal advice and support to law enforcement agencies over the course of investigations that may lead to such prosecutions.

Public Safety Canada (PS)

PS provides policy coordination for the Initiative, including leading evaluations. PS is responsible for chairing the IPOC Senior Governance Committee, and coordinates the working level IPOC Partners Advisory Committee.

Public Works and Government Services Canada - Forensic Accounting Management Group (PWGSC - FAMG)

PWGSC-FAMG provides forensic accounting services to the IPOC units and expert witness testimony on the financial aspects of the criminal investigations and prosecutions.

Public Works and Government Services Canada - Seized Property Management Directorate (PWGSC - SPMD)

As a service provider, PWGSC-SPMD manages the assets seized or restrained under Canada's Proceeds of Crime legislation. PWGSC-SPMD works with federal police officers and Crown prosecutors on cases involving restraint, seizure and forfeiture by providing expertise for efficient and effective asset management and disposal. The costs of the asset management are deducted from the revenues generated from forfeited assets, including but not limited to those forfeited as proceeds of crime.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP)

Lead agency responsible for the daily operation and management of each of the IPOC, POC and satellite units.

Other non-Federal Partners

In addition to the federal partners and service providers, provincial and municipal police and prosecutors are integrated or collaborate with several IPOC units. This integration/collaboration with non-federal partners is defined in local memoranda of understanding (MOUs).

2.3 IPOC Units

Since 2003, IPOC units have been located in 12 municipalities across Canada. Table 2 outlines each unit, identifying the responsible division, federal in-house partnersNote 9 (i.e. co-located in the same office) and the filled position over six years (based on data provided by partners).

| City | Division | In-house Partners | Filled positions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 05-06 | 06-07 | 07-08 | 08-09 | 09-10 | |||

| Halifax (NS) | Division H | CRA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PPSC | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||

| PWGSC-FAMG | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| RCMP | 8 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 8 | ||

| Total | 13 | 12 | 14 | 13 | 13 | ||

| Moncton (NB) | Division J | CRA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PPSC | 2 | 1.5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| PWGSC-FAMG | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| RCMP | 12 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 14 | ||

| Total | 16 | 14.5 | 15 | 14 | 16 | ||

| Quebec City (QC) | Division C | CRA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PPSC | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| PWGSC-FAMG | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| RCMP | 9 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 10 | ||

| Total | 13 | 14 | 16 | 15 | 14 | ||

| Montréal (QC) | Division C | PPSC | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| PWGSC-FAMG | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||

| RCMP | 47 | 49 | 50 | 44 | 48 | ||

| Total | 54 | 56 | 58 | 52 | 54 | ||

| Ottawa (ON) | Division A | CBSA | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRA | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||

| PPSC | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||

| PWGSC-FAMG | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| RCMP | 11 | 8 | 11 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Total | 21 | 18 | 18 | 17 | 16 | ||

| Toronto (ON) | Division O | CBSA | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRA | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| PPSC | 2 | 3.5 | 2 | 1.5 | 1.5 | ||

| PWGSC-FAMG | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| RCMP | 36 | 37 | 36 | 33 | 34 | ||

| Total | 43 | 45.5 | 41 | 36.6 | 36.5 | ||

| London (ON) | Division O | CBSA | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PPSC | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | ||

| PWGSC-FAMG | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| RCMP | 14 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 16 | ||

| Total | 20 | 25 | 24 | 23 | 20 | ||

| Winnipeg (MB) | Division D | PPSC | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| PWGSC-FAMG | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| RCMP | 12 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 12 | ||

| Total | 15 | 15 | 13 | 13 | 15 | ||

| Regina (SK) | Division F | CRA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PPSC | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| PWGSC-FAMG | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| RCMP | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 5 | ||

| Total | 9 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 8 | ||

| Calgary (AB) | Division K | CRA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PPSC | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| PWGSC-FAMG | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| RCMP | 14 | 15 | 12 | 16 | 14 | ||

| Total | 17 | 18 | 15 | 19 | 17 | ||

| Edmonton (AB) | Division K | CRA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PPSC | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| PWGSC-FAMG | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| RCMP | 15 | 15 | 15 | 12 | 15 | ||

| Total | 19 | 19 | 19 | 16 | 19 | ||

| Vancouver (BC) | Division E | CBSA | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PPSC | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | ||

| PWGSC-FAMG | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||

| RCMP | 36 | 34 | 35 | 32 | 38 | ||

| Total | 43 | 41 | 41 | 38 | 41 | ||

There are also four smaller satellite units located in:

| City | Division | In-house Partners | Filled positions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 05-06 | 06-07 | 07-08 | 08-09 | 09-10 | |||

| Sherbrooke (QC) | Division C | RCMP | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Kingston (ON) | Division O | RCMP | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Niagara (ON) | Division O | RCMP | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Saskatoon (SK) | Division F | RCMP | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 7 |

| Kelowna (BC) | Division E | RCMP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

Finally, the RCMP has two POC units located in:

| City | Division | In-house Partners | Filled positions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 05-06 | 06-07 | 07-08 | 08-09 | 09-10 | |||

| St. John's (NL) | Division B | RCMP | 6 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| CRA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Total | 7 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| Yellowknife (NWT) | Division G | RCMP | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

2.4 IPOC Governance Structure

The Initiative is managed by three complementary governance entities.

IPOC Senior Governance Committee

The IPOC Senior Governance Committee provides general oversight for the Initiative at the director general level or delegate. The Committee, which is chaired by PS and includes representatives from each IPOC partner, meets on an as required basis. Its role is to provide direction, promote interdepartmental policy coordination and accountability, and champion the program.

IPOC Partners Advisory Committee (Advisory Committee)

The IPOC Partners Advisory Committee, with representatives from each partner organization at the director or senior analyst level, meets bi-annually or as appropriate to address issues. The Committee supports the development of the evaluation strategy, and implements the monitoring and tracking processes required to effectively manage and support the evaluation of the program. The Committee is also responsible for providing support to the IPOC Senior Governance Committee, promoting interdepartmental cooperation, and resolving horizontal operational issues. It is chaired by PS.

Day-to-Day Operations

The RCMP retains responsibility for the day-to-day management and operations of the IPOC units, with other partners responsible for the day-to-day management and operations of their related components. At the regional level, members of the IPOC partnership meet regularly to discuss and resolve local and regional issues.

2.5 IPOC Resources

2.5.1 Financial Resources

The Initiative was allocated $116.5 million over five years in 2005. This is the same amount, unadjusted for inflation that was allocated in 1996-1997 when the Initiative was created. Table 5 outlines the funding for each partner during the 2005-2006 to 2009-2010 period. CRA did not receive any financing through the Initiative, and therefore is not included in the table.

| Fiscal Years | 2005-2006 | 2006-2007 | 2007-2008 | 2008-2009 | 2009-2010 | Total 2005-2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) | ||||||

| Funding | $390,000 | $390,000 | $390,000 | $390,000 | $390,000 | $1,950,000 |

| Public Prosecution Service of Canada (PPSC) | ||||||

| Funding | $6,050,000 | $6,050,000 | $6,050,000 | $6,050,000 | $6,050,000 | $30,250,000 |

| Public Works and Government Services Canada - Forensic Accounting Management Group (PWGSC-FAMG)* | ||||||

| Funding | $1,700,000 | $1,700,000 | $1,700,000 | $1,700,000 | $1,700,000 | $8,500,000 |

| Public Safety Canada (PS) | ||||||

| Funding | $160,000 | $160,000 | $160,000 | $160,000 | $160,000 | $800,000 |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) | ||||||

| Funding | $15,000,000 | $15,000,000 | $15, 000,000 | $15,000,000 | $15,000,000 | $75,000,000 |

| Total for all IPOC Partners | ||||||

| Funding | $23,300,000 | $23,300,000 | $23,300,000 | $23,300,000 | $23,300,000 | $116,500,000 |

* In addition to their A-Base funding, PWGSC-FAMG has received per diem payments from RCMP for seven additional accountants for a total of $1,300,000 per year for the past five years.

2.5.2 Human Resources

Table 6 presents the FTE variation for the period covered by this evaluation.

| Fiscal Years | 2005-2006 | 2006-2007 | 2007-2008 | 2008-2009 | 2009-2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) | |||||

| Filled Positions | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Vacant Positions | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) | |||||

| Filled Positions | 13 | 13 | 11 | 10 | 8 |

| Vacant Positions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Public Prosecution Service of Canada (PPSC) | |||||

| Filled Positions (advisory counsel) | 29 | 30 | 29 | 26.5 | 26 |

| Filled Positions (prosecutors)Note 10 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Vacant Positions | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Public Safety Canada (PS) | |||||

| Filled Positions | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Vacant Positions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Public Works and Government Services Canada - Forensic Accounting Management Group (PWGSC - PWGSC-FAMG ) | |||||

| Filled Positions | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Vacant Positions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) | |||||

| Filled Positions | 256 | 258 | 251 | 247 | 257 |

| Vacant Positions | 63 | 61 | 66 | 71 | 59 |

3. About the Evaluation

3.1 Evaluation Approach

Public Safety Canada (PS) is responsible to lead evaluation activities.

This evaluation complies with the Treasury Board of Canada SecretariatPolicy on Evaluation.

An Evaluation Advisory Committee was established with representatives from both the program and evaluation sides of all participating departments and agencies. The committee was chaired by the PS Evaluation lead. Prior to initiating this evaluation, PS completed an evaluability assessment for the Initiative in collaboration with participating departments and agencies. The evaluability assessment established the structure for the evaluation and helped identify the readiness level for its completion. Its development involved managers, staff and evaluators of all IPOC partner organizations.

3.1.1 Evaluation issues

In conformity with the TBS Directive on the Evaluation Function, five core issues were addressed in the evaluation, with regards to the Initiative's relevance and performance:

Table 7 - Evaluation Issues

Relevance

- 1. Continued need for the Initiative

- Assessment of the extent to which the program continues to address a demonstrable need and is responsive to the needs of Canadians.

- 2. Alignment with federal government priorities

- Assessment of the linkage between program objectives and federal government priorities and departmental strategic outcomes.

- 3. Alignment with federal roles and responsibilities

- Assessment of the role and responsibilities for the federal government in delivering the program.

Performance

- 4. Achievement of expected outcomes

- Assessment of progress toward expected outcomes (incl. Immediate, intermediate and ultimate outcomes) with reference to performance targets and program reach, program design, including the linkage and contribution of outputs to outcomes.

- 5. Demonstration of efficiency and economy

- Assessment of resource utilization in relation to the production of outputs and progress toward expected outcomes.

3.1.2 Evaluation Framework

The issues, questions, and proposed data gathering methods were shared and discussed with the members of the Evaluation Advisory Committee on July 7, 2010. The final evaluation terms of reference were approved by all IPOC partners in the following weeks.

3.1.3 Evaluation Questions Matrix

Complementarily to the framework, an Evaluation Questions MatrixNote 11 was developed prior to the data collection phase. For each of the five evaluation issues, the matrix presents evaluation questions, indicators, and the proposed data collection method(s) for each indicator.

In total, 14 evaluation questions and 50 indicators were identified in the matrix and have been used to develop the data collection tools presented below.

The Evaluation Question Matrix was approved by the Evaluation Advisory Committee on August 12, 2010.

3.2 Data Gathering

During the process, the evaluation team pursued different lines of evidence from multiple perspectives. This approach was designed to yield important insights, while allowing for triangulation to deepen the analysis. The data were subsequently integrated and synthesized to support key findings and recommendations.

Quantitative and qualitative data were provided by all IPOC partners; when required, further research and analysis was performed by the evaluation team. Therefore, the evaluation team is confident that the evidence is sufficient to answer most of the questions, and that the key findings are accurate and reliable, and support the conclusions and recommendations.

Four methods were used:

- document and literature review;

- key representatives interviews and group interviews;

- database review and analysis; and,

- case studies.

Following is a summary of the data collection methods used.

3.2.1 Document and literature review

The document and literature review provided the evaluators with an understanding of the Initiative's context, environment and evolution over time. It also provided some reliable key data for many of the indicators.

The review covered a wide variety of materials including: action and business plans, the Result-based Management and Accountability Framework (RMAF), previous audits and evaluations, annual reports, MOUs between IPOC partners, international agreements and protocols, media reports, and other documents from related initiatives (e.g. AML/ATF, Integrated Market Enforcement Teams (IMET), National Anti-Drug Strategy (NADS), etc).

A literature review was also performed and included books and other scholarly works written by national and international experts in organized crime and money laundering.

A complete list of the documents and literature reviewed during this evaluation is provided in Appendix A.

3.2.2 Key Representative Interviews and Group Interviews

The evaluation team started with six initial, non-structured interviews with nine members of the Advisory Committee. These interviews included every representative from IPOC partners and were conducted in order to gather background information in preparation for the data collection phase.

The evaluation team subsequently conducted face-to-face, semi-structured interviews/group interviews with 55 key representatives from IPOC units located in eight cities across the country - Calgary, London, Moncton, Montréal, Ottawa, Quebec City, Toronto (Newmarket) and Vancouver (Surrey)Note 12 - including four members of the Advisory Committee. Given the length of the questionnaire, every interviewee was invited to complete it prior to the meeting. A single version of the questionnaire was used for all interviews, so as to ensure coherence and consistency across interviews.

The questionnaire was composed of 19 non-structured questions and 21 structured questions. For the structured questions, respondents were asked to rate statements using the following scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is "not at all needed" and 5 "needed to a great extent".

| 1 (not at all) |

2 (minimal) |

3 (somewhat) |

4 (significant) |

5 (great extent) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0-1.49 | 1.5-2.49 | 2.5-3.49 | 3.5-4.49 | 4.5-5.0 |

The key findings for each interview were compiled into an Evaluation Evidence Matrix, with randomly selected numbers assigned to each key representative in order to protect their confidentiality.

Non-structured follow-up interviews were also conducted with headquarters' staff from PS, the RCMP, and PPSC.

Table 8 presents the number of key representatives interviewed by IPOC partner, including the members of the Advisory Committee and the representatives of the IPOC units visited.

| Key Representatives | IPOC Partners | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBSA | CRA | PPSC | PS | PWGSC-FAMG | RCMP | |

| Total | 12 | 3 | 13 | 3 | 7 | 22 |

3.2.3 Database review and analysis

The IPOC Partners provided various quantitative and qualitative data from their databases. These data are a key source of information to measure the outputs and outcomes of the Initiative. The evaluation team gathered administrative, financial and transactional data providing information and specific reports that allowed, when combined, measurement of progress of the Initiative towards its outcomes.

3.2.4 Case studies

To facilitate the in-depth examination of a specific event considered representative of a typical situation, the authors have studied a few cases. These case studies are aimed at providing insight as to whether the results were achieved and actions were taken by the partners. Two of these cases are documented in section 4.2.1.1. (Opération Colisée and Operation Baseball).

3.3 Methodological Limitations

During the evaluation process, the authors faced three main methodological constraints that held implications for the subsequent data analysis and interpretation.

Data Availability

All IPOC partners have their own reporting systems and tools, and no common standard exists among them. Thus, the partners provided a wide range of data, and the quantity varied greatly from one partner to another. In some cases, it was impossible to compare specific variables between the partners. In addition, some partners were unable to provide all of the data requested by the evaluation team.

Data Validity and Reliability

In the course of the collection of data, the authors learned that some quantitative data might be contaminated by various factors (sources used, reporting tools, procedures, etc.) affecting their validity (the right measure) and reliability (quality of the measure). The evaluation team has been very cautious with these data; where applicable, the authors addressed the limitations of these data in the report.

Causality between activities and outcomes

The nature and the context of the Initiative make it difficult to prove beyond any doubt the causality between certain activities and outcomes, especially for the intermediate and ultimate outcomes. In such cases, to prove causation between an initiative's activity and an outcome, the evaluation team would need to isolate the dependent and independent variables from all possible external factors and influences. Thus, it is important to note that some of the outcomes measured could be a result of multiple factors, either internal or external to the Initiative. Some caution must be exercised in attributing results directly and solely to the Initiative. In most cases, intermediate and ultimate outcomes are in fact attributable to a combination of initiatives related to combating organized crime.

4. Findings

The following sections provide key findings regarding the two core issues, relevance and performance, covered by this evaluation. The key findings which follow are derived from the methodology and lines of evidence described in Section 3.

4.1 Relevance

In order to assess the Initiative's relevance component, three relevance issues and five evaluation questions were addressed, as noted in Table 9.

| Relevance Issues | Relevance Questions | |

|---|---|---|

| 4.1.1 | Continued need for program | 4.1.1.1 Is there a continued need for the IPOC Initiative? |

| 4.1.1.2 To what extent are the objectives of the IPOC Initiative (i.e. targeting their illicit proceeds and assets) still relevant to fight organized criminals and crime groups? | ||

| 4.1.1.3 To what extend is the IPOC Initiative theory and design appropriate in addressing ongoing needs? | ||

| 4.1.2 | Alignment with federal government priorities | 4.1.2.1 To what extent does the IPOC Initiative contribute to the policy priorities of Government with respect to organized criminals and crime groups and activities? |

| 4.1.3 | Alignment with federal roles and responsibilities | 4.1.3.1 Is the IPOC Initiative aligned with Government of Canada roles and responsibilities? |

4.1.1 Continued Need for Program

4.1.1.1 Is there a continued need for the IPOC Initiative?

Organized crime is considered as one of the major threats to national security, impeding the social, economic, political and cultural development of societies worldwide. It is a multi-faceted phenomenon and has manifested itself in different activities, among them: drug trafficking, trafficking in human beings, trafficking in firearms, smuggling of migrants, money laundering, proceeds of crime, etc. In particular, drug trafficking is one of the main activities of organized crime groups, generating enormous profits.

In Canada there were approximately 750 criminal groups identified in 2009Note 13. As stated in a Public Report on Actions under the National Agenda to Combat Organized CrimeNote 14, "since organized criminals seek out countries known to have less effective regulatory and enforcement systems, any jurisdiction that does not have adequate defences is at risk and may cause risk to other countries. As perhaps never before, the policies and enforcement capabilities of any one country have direct consequences globally". The Initiative is one of the tools Canada gave itself to fight organized criminals and criminal groups. IPOC focuses on identifying, assessing, seizing, restraining and dealing with the forfeiture of illicit wealth accumulated through criminal activities.

Targeting proceeds of crime has been put forward by many specialists as one of the most effective approaches in the fight against organized crime. In this regard, the Canadian government, through its National Agenda to Combat Organized Crime, is committed to working with provinces, municipalities, and international partners to protect its citizens and the country's economic infrastructure against organized crime. Proceeds of crime investigations, prosecutions, seizures and forfeitures are key tools for the Government in its fight against organized crime.

The literature reviewed overwhelmingly supports the need for continuing efforts to combat organized crime by targeting proceeds of crime. For example, in its Treasury Forfeiture Fund: Strategic Plan (2000-2005), the U.S. Department of the Treasury concludes that: "the only real damage that can be done to drug cartels and criminal syndicates is the removal of facilitating assets and the profit incentive on a significant scale"Note 15.

Researchers in the field of criminology and law have also made a strong case for continued efforts aimed at fighting organized crime through the removal of their assets. According to Lyman and Potter, "operations to combat money laundering and to deprive such groups of the proceeds of crime can deprive them of this key flow of money. The forfeiture of assets obtained through crime also is said to remove the incentive from engaging in unlawful behaviour"Note 16.

The review of international activities also indicates firm support for the targeting of assets as a powerful method for fighting organized crime. "All recognize the importance of removing ill-gotten gains, to take the profit out of crime, and to reduce the capacity of organized crime to undertake criminal activities"Note 17.

Notably, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an inter-governmental policy-making body comprised of over 30 countries, recommends endorsing global standards for implementing effective Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing (AML/CTF) measures.

Consistent with IPOC objectives, the first two steps to effectively implementing FATF recommendations are as follows:

- Successfully investigate and prosecute money laundering and terrorist financing;

- Deprive criminals of their criminal proceeds and the resources needed to finance their illicit activitiesNote 18.

Through our interview process, personnel from departments and agencies involved in the IPOC Initiative, significantly agreed (average of 4.39) that there is a continued need for the IPOC Initiative.

Changes in the context and environment related to the IPOC Initiative

In order to assess the continued need for the Initiative, the evaluators examined the changes in context and environmental changes, both externally and internally, that affect the Initiative.

Over the years, the Canadian government has implemented various strategies to combat money laundering and to confiscate the proceeds of crime. One of these strategies was the Integrated Anti-Drug Profiteering Initiative, which was the precursor to IPOC - that demonstrated that an integrated approach to combating proceeds of crime improved the success of investigations and prosecutionsNote 19.

Over the past five years, however, the context and environment in which the IPOC Initiative operates has changed significantly, both externally and internally:

External Changes

The growing sophistication of organized criminals and crime groups represents an important global trend in recent years. As stated by a key informant: "Criminals have become more complex in the way they conduct their activities (the nexus between the dirty money and the assets is not as simple as it may have been in the past). They have become more sophisticated. They have learned to use nominees to hold assets, to lease instead of buying a vehicle, to have someone else hold the house they are renting for grow operation [...]. With Proceeds of Crime analysis, you can often disprove these defences by examining bank records, loan applications, and other financial information. Definitively, criminal organizations are now requiring more complex investigations that require a wide range of experts. This illustrates why the IPOC Initiative is required to be continued."Note 20.

Another important trend is the increasing interest and involvement of provincial and territorial governments. Several key representatives indicate that provincial and municipal forces are achieving tangible results on their own using civil forfeituresNote 21. Evidence of the involvement of the provinces can be found also in the growing number of civil forfeiture statutes. The next section (4.1.1.2) describes these new provincial legislative tools.

International organizations such as FATF and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime have put pressure on Canada to address the problems of money laundering and, by extension, the proceeds of crime. In Canada's Report on FATF Observance of Standards and Codes (2008), the Government of Canada committed to: "bolstering money laundering and terrorist financing enforcement and prosecution"Note 22. For the authors of the report, this commitment goes beyond the Anti-Money Laundering/Anti-Terrorism Financing (AML/ATF) Regime and includes a "proceeds of crime" component.

Internal Changes

The context and environment have changed and have become a challenge for the IPOC Initiative. While IPOC partners agree that the Initiative ought to be maintained and even augmented, budget restrictions, lack of human resources and experience have resulted in IPOC having more difficulty responding to the partners' operational needs (e.g. information and intelligence), attracting and maintaining talented personnel, and achieving results.

Since 2005, seven IPOC units - Halifax, Moncton, Quebec City, Ottawa, Toronto (Newmarket), London and Vancouver (Surrey) - saw the physical departure of in-house partners (PPSC, CBSA and CRA), as well as provincial and municipal law enforcementNote 23. For example, CBSA Intelligence officers are no longer co-located in any IPOC units. PPSC prosecutors are no longer co-located in units such as Moncton and Vancouver. Also, many of the provincial and municipal police forces that had joined IPOC units previously have now left them and have integrated "civil forfeiture structures" at their level.

Relationships among some partners (particularly between RCMP, PPSC and CBSA) can be described as mixedNote 24. For example, the RCMP's report, Proceeds of Crime Review: National Report 2005-2007 indicated that the results of RCMP's working relationship with CBSA varied from non-existent (with no Level IV referrals) to good (with weekly referrals)Note 25. Our interviews with CBSA personnel show, on one hand, a level of frustration from the Agency due to the inability of most IPOC units to respond to the needs of CBSA, namely in the exchange of intelligence. Furthermore, CBSA feels that there is still a prevailing misunderstanding as to what legislative authorities come into play. On the other hand, the RCMP recognized the benefit of having CBSA as an in-house partner, stating that their intelligence work greatly increased the effectiveness of investigations, and enhanced relationships and information sharing. Similarly, investigators and prosecutors in some locations spoke of collaborative and respectful working relationships while others alluded to more adversarial and ineffective relationships. Such differences may be due, at least in part, to a lack of understanding of their respective roles and requirements.

Overall, most of those interviewed stated that the Initiative is no longer the "flavour of the day", and, over the years, it has lost some of its appeal to new priorities and newer initiatives such as the AML/ATF Regime and the IMETNote 26.

Also, proceeds of crime prosecutions tend to be more and more complex and time consuming. Some PPSC prosecutors indicate that such prosecutions can take between three to five years, unlike civil forfeiture or drug offences, which can be completed in a shorter time span.

The majority of IPOC partners also state that budget limitations are a serious constraint to fulfilling the mandate of the Initiative. This lack of funding has had multiple impacts on how each partner views the performance of the Initiative and, by extension, its relevance. For example:

- All RCMP representatives interviewed agree that the IPOC unadjusted budget (same budget as in 1996-1997) impacted their capacity to fill IPOC positions at the approved staff levels (from 357 FTE to 256 FTE in the last six years). Investigation and assistance requests placed on the IPOC units have increased, but the capacity of the IPOC units to respond to those demands has diminishedNote 27. The RCMP representatives at most of the IPOC units visited explained that they had to carefully select cases to investigate due to the lack of staff.

- PWGSC-FAMG budget set at $1.7 million per year has remained the same since the creation or the Initiative. In addition to their funding, PWGSC-FAMG receive per diem payments from RCMP for additional accountants for a total of $1.3 million per year for the past five years. PWGSC-FAMG being a "cost recovery" entity indicates that it will not be in a position to continue supporting the Initiative under the current arrangement. It intends to renegotiate its fees in the very near future.

- CRA, unlike the other partners, is not a funded partner and has therefore full discretion in providing (or not providing) resources to IPOC units. Like CBSA, CRA has vacated most of the IPOC units. The number of CRA Supernumerary Special Constables was down from 13 in 2006-2007 to four in 2010-2011.

Federal and provincial legislative environment

As indicated above, there have been some changes to the legislative environment, both federally and provincially.

Federal legislation

On December 15, 2006, the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act was amended, ensuring that Canada would continue to be a global leader in combating organized crime and terrorist financing. The amendments included:

- enhancing information sharing between the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centers in Canada (FINTRAC), law enforcement and other domestic and international agencies;

- creating a registration regime for money service businesses;

- enabling the legislation for enhanced client identification measures; and,

- creating an administrative and monetary penalties regime to better enforce compliance with the Act.

Most of the key representatives interviewed indicate that those amendments had little or no impact on the Initiative. Generally speaking, many of the interviewees are of the view that the current legislative environment limits the sharing of information between the IPOC partners and therefore is counterproductive (see Section 4.2.1.5.). This information sharing problem is particularly acute between CRA, CBSA and RCMP, and is primarily due to privacy concerns and legislation restrictions.

Another issue influencing the federal legal environment is associated with offence related property. Offence related property is defined as any property with which a designated offence is committed, that is used in connection with the commission of a designated offence, or that is intended for use for the purpose of committing a designated offence. A court that convicts a person of a designated offence shall order the forfeiture of offence-related property where it is satisfied, on a balance of probabilities, that the property is offence-related propertyNote 28. Most of the persons interviewed acknowledged that offence related property was a positive tool to forfeit assets quickly. As stated by one key informant: "In recent years, probably due to the sophistication in proving or charging proceeds of crime cases, more cases are leaning toward criminal property charges instead."Note 29.

Finally, recent legislative amendments to the Criminal Code to include all of the offences under the Income Tax Act as predicate offences for money laundering, were introduced in 2010, and Canada's October 2007 ratification of the United Nations Convention Against Corruption.

To conclude, for many, the federal legal environment has presented more and more obstacles to the success of the Initiative. As one interviewee puts it, "The legislative environment has been slow to react to international and country-wide jurisdiction issues, including issues such as: production orders, search warrants, and disclosures."Note 30. Many share the view that the law has become more complicated in regard to disclosures, production orders and in the exchange of information among the different partnersNote 31. These recent legislative changes and the responsibilities that they entail have brought additional pressures to bear on the IPOC Initiative's human resources complement.

Provincial legislation

While there have been changes to legislation at the federal level, the greatest impact has come from the provincial level.

Changes to the legal environment have made provinces and municipalities more present in the fight against organized crime and have impacted the work conducted by the IPOC units. Civil forfeiture has increased and is being used to a greater extent than in the past. Some IPOC units have contributed, and continue to contribute to the work initiated at the provincial and municipal levels, and have transferred and continue to transfer cases to them. Many voices support a renewed work relationship with the provinces and municipalities, and consequently a repositioning of the IPOC Initiative.

The legislative environment, particularly at the provincial level has changed: civil forfeiture came in and influenced the way cases are approached and dealt withNote 32. As one interviewee summarized it, "civil forfeiture is a very powerful tool. Civil forfeiture and offence-related property have provided a more direct route to seize valuable assets"Note 33.

Over the past years, provinces and municipalities have given themselves the required tools to act quickly against organized criminals and crime groups. Basing their action on civil forfeiture legislation that allows for quick results, they have created enforcement structures that have changed the nature and level of their participation in the federal IPOC unitsNote 34. In addition, the dollar value of seizures and confiscations going to the provinces, rather than to the federal government, has been an incentive for them to move in that direction. Our interviews indicate that over the past few years, there has been a steady increase in cases transferred to the provinces. This view is also supported by Ontario civil forfeiture data (see Figure 8). Two factors appear to explain this: 1) The inability for many IPOC units to sustain large numbers of IPOC investigations leading to criminal charges; 2) the ease of transferring cases to the provinces under the civil forfeiture legislation, which result in quick seizure and forfeiture of illegal assets.

Generally, many partners see civil forfeiture as a positive trend. For example, several RCMP officers taking part in the interviews welcome the provincial civil forfeiture expansion. For them, provincial civil forfeitures constitute a good vehicle to deprive criminals of illegal assets. As one interviewee mentioned: "We have to go criminal first [...] if we don't lay charges, then we can refer these cases to civil forfeitures."Note 35. For those files not considered as "major files" (see Section 4.2.1.1), many officers favour civil forfeiture legislation, as it allows for a quick and effective forfeiture of assets of organized criminals and crime groups; this is especially beneficial for those IPOC units that have scarce resources. In recent years, the RCMP contributed to the increase of civil forfeitures by referring many cases to the provincesNote 36. Civil forfeiture is also supported by international organizations such as FATF and other governments through their legislation (for example the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations in the United States).

It is important to understand that criminal and civil asset forfeiture differ in the procedure and burden of proof required to forfeit assets. The main distinction between them is that criminal forfeiture requires a criminal process against an accused, whereas civil asset forfeiture is an action against the asset itself, and not against an individual. In civil forfeiture, the asset could be forfeited but the owner will not be accused under the Criminal Code. There is no further investigation completed to determine other unreported wealth owned by the suspected criminal. In all cases, an investigation is required to identify the asset owners and then link the property to criminal activity.

4.1.1.2 To what extent are the objectives of the IPOC Initiative (i.e. targeting their illicit proceeds and assets) still relevant to fight organized criminals and crime groups?

IPOC partners strongly agree that the Initiative and objectives are still relevant. For example, there is consensus among the RCMP that the Initiative and its objectives are essential to fighting organized crime. As illustrated by one representative, "money is the motivator for criminals, so what we try to do is take the profit out of crime. It wasn't that long ago that criminals (also criminals from the United States) were walking into banks in Montréal with hockey bags full of money and legally depositing [the proceeds] into bank accounts without any questions being asked"Note 37. Other IPOC partners share this same view. All of those interviewed agree that seizing assets gained illegally remains the best and most effective way to fight organized crime, and that the Initiative should maintain its focus on organized crime, at both the upper and lower echelons.

4.1.1.3 To what extent are the Initiative theory and design appropriate in addressing ongoing needs?

"The logic of proceeds of crime enforcement is simple, and it is seductively attractive to governments and law enforcement doing battle with organized crime and, more recently, with terrorism. As an enforcement strategy targeting criminal entrepreneurs and organizations, confiscating the proceeds of crime is meant to achieve [three interrelated] objectives. First, it punishes offenders by depriving them of the fruits of their trade. Second, it strives to remove the incentive for an offender to engage in profit-oriented criminal activities. Third, it is meant to reduce the financial power base from which criminal organizations can operate"Note 38.

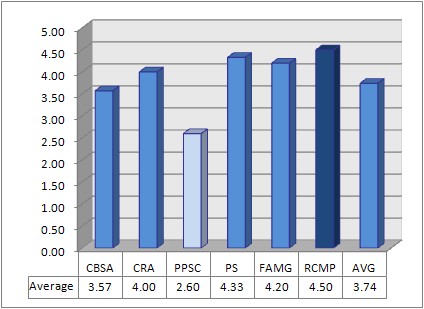

From its inception, the IPOC Initiative has subscribed to a theory similar to the one described by Beare and Schneider in their book titled Money Laundering in Canada published in 2007. During the interviews and as illustrated in Figure 3, all of the key players in the IPOC Initiative, except for PPSC, significantly supported the statement that the IPOC theory and design were still appropriate. The concerns expressed by PPSC representatives related mainly to the existing design of the Initiative, and to a lesser extent with planning and relations among partners.

Figure 3 - Relevance of the Initiative's Theory and Design

Image Description

Bar chart showing the average of interviewee responses by organization—CBSA: 3.57, CRA: 4.00, PPSC: 2.60, PS: 4.33, FAMG: 4.20, RCMP: 4.50, average: 3.74

Many interviewees from PPSC, CBSA and the RCMP expressed ideas along the lines of those articulated by the authors noted above. While the theoretical underpinnings of the Initiative seem to be appropriate on the surface, criminals have learned to adapt. As Beare points out, "while we might be able to assert the first objective (depriving them the fruits of their trade), 'Deterrence' theory in relation to any form of criminality lacks credibility - perhaps even more so with organized criminals or persistent criminals of any sort. Such criminals speak of the 'cost of doing business' and, short of an all-out enforcement assault culminating in massive imprisonments and near-total confiscation, the criminal operations appear to take most seizures in stride. It must be also asked whether the most serious and most sophisticated criminals are even suffering these minor enforcement successes"Note 39.

A major component of the IPOC design is the integration of partners to collaborate closely on IPOC files. While the concept of "integration" could refer to either "co-location" or "remote collaboration" using information technology enabling tools, several key representatives suggest that the physical departure of some partners (CBSA, PPSC, CRA) from within the IPOC units has compromised the integration aspect of IPOC. As stated by one representative, "The original design was to utilize an integrated approach involving municipal/regional, provincial police and other federal agencies. This is a very valid approach as each agency brings expertise and resources to the unit. While it is still integrated to some extent this has diminished over time and not all of the original partners are involved, as many have left"Note 40.

4.1.2 Alignment with Federal Government Priorities

4.1.2.1 To what extent does the Initiative contribute to the policy priorities of Government with respect to organized criminals and crime groups and activities?

Over the past five years, the Government of Canada has steadily underlined the fight against organized crime as a priority. Speeches from the Throne (2006-2010), official public documents, and press releases all identify the fight against organized crime as priorities for the Canadian government.

The Government regularly refers to its fight against organized crime as a priority. For example, following a series of discussions with their provincial counterparts, the then-Minister of Justice/Attorney General and the then-Minister of Public Safety reaffirmed, in June 2007, the federal government's commitment to tackling organized crime: "Organized crime has an impact on the daily lives of Canadians, affecting our families, our businesses, our possessions, our health and our bank accounts. This Government is taking action to combat organized crime, and we're delivering significant measures through our legislative agenda to tackle this problem. Canada's New Government made a commitment to tackle crime and we have already announced key initiatives to bolster Canada's capacity to combat illegal smuggling, crack down on money laundering and increase border security. We are working with our provincial and territorial partners to fight organized crime in our communities and make our streets safer"Note 41.

In recent years, the federal government has brought forward a number of legislative initiatives to disrupt organized crime, one of which was the Amendments to the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act. When the amendments received Royal Assent on December 14, 2006, a number of measures to fight organized crime and terrorism where announced. These included:

- Providing for an additional 1,000 RCMP personnel;

- Enhancing border security by arming border officers;

- Investing $9 million over two years to set-up counterfeit currency enforcement teams across Canada;

- Committing $64 million over two years in Budget 2007 to establish a National Anti-Drug Strategy;

- Providing an additional $6 million per year to strengthen existing initiatives to combat child sexual exploitation and human trafficking; and,

- Helping establish, through $5 million in funding over five years, a permanent location in Toronto for the Egmont Group, a global organization aimed at combating international money laundering and terrorist financing.

For many of the interviewees, the IPOC Initiative is one of the tools in the Government's effort to protect the public and fight organized crime. However, RCMP representatives indicate that the Initiative did not receive any additional funding from this announcement.

Consistent with government priorities, the IPOC Initiative focuses on the "money" aspect of organized crime. It investigates the flow of money, transactions, and the acquisition of assets such as residences, buildings, cars, boats, etc. so as to determine if the goods were acquired illegally or not, or if the gains originated from legal or illegal activities. In the cases where it is established that the acquisition of assets was illegal, assets are seized, and if the required burden of proof is met, forfeited.

Most respondents from participating organizations agree that IPOC is significantly aligned with the policy priorities of the Government of Canada's fight against organized crime (Figure 4). However, the CRA and PPSC representatives tended to base their responses on the results of the Initiative rather than its theory. These respondents have concerns about what they perceive as the limited impact of the Initiative on disrupting, dismantling and deterring organized crime, especially in the past few years.

Figure 4 - Alignment with Policy Priorities of GOC

Image Description

Bar chart showing the average of interviewee responses by organization-CBSA: 4.13, CRA: 2.00, PPSC: 3.00, PS: 5.00, FAMG: 4.00, RCMP: 4.47, average: 3.63

4.1.3 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

4.1.3.1 Is the Initiative aligned with federal government roles and responsibilities?

Ultimately, the authority to combat organized crime at the federal level is embedded in the Canadian constitution, which states "It shall be lawful for the Queen, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate and House of Commons, to make laws for the Peace, Order, and good Government of Canada"Note 42. Section 91(27) also stipulates that the federal government has the authority over criminal law and procedure in criminal matters.

Today, several federal departments play a significant role in ensuring the safety and security of Canadians. Specifically, PS plays a key role in "coordination across all federal departments and agencies responsible for national security and the safety of Canadians"Note 43. PS works with five agencies (CBSA, RCMP, Canadian Security Intelligence Service, Correctional Service Canada and Parole Board of Canada). These agencies are part of the same portfolio and report to the same minister. The result is better integration among federal organizations dealing with national security, emergency preparedness and management, law enforcement, corrections, crime prevention and border control.

One of the main roles of the PS portfolio is the fight against organized crime. Its work is guided by the National Agenda to Combat Organized Crime, which was developed and approved by federal, provincial and territorial law enforcement partners. IPOC responds to this role, as one of the main initiatives identified to fight against organized crime.

Proceeds of crime investigations and prosecutions are key tools in the Canadian government's overall effort to combat organized crime activities. Both nationally and internationally, the federal government has confirmed its ongoing commitment to fight organized crime. Indeed, the federal government participates in several international organizations such as FATF, the Egmont Group and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and has signed a number of international agreements, such as Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties.

On a national level, the Initiative is linked to the AML/ATF Regime, Combined Forces Special Enforcement Units and the National Anti-Drug Strategy. It also collaborates with provinces and municipalities through a series of MOUs.