2024 Annual Report to Parliament on the Fighting Against Forced Labour and Child Labour in Supply Chains Act

Table of contents

Introduction

The 2024 annual report is tabled in Parliament in accordance with subsection 24(1) of the Fighting Against Forced Labour and Child Labour in Supply Chains ActFootnote 1 (Supply Chains Act) (see footnote below), under the direction of the Minister of Public Safety, and covers the first reporting period of the Supply Chains Act.

The first year of reporting under the Supply Chains Act is a milestone in Canada’s efforts to promote responsible business conduct and safeguard human rights, both at home and abroad. This report provides an overview of the risks of forced labour and child labour that reporting entities and government institutions have identified in their activities and supply chains, as well as the steps these organizations have taken to address the risks.

About the Supply Chains Act

Purpose and application

The purpose of the legislation is to contribute to the implementation of Canada's international commitment to the fight against forced labour and child labour, through the imposition of reporting obligations on:

- government institutions producing, purchasing or distributing goods in Canada or elsewhere; and

- entities producing goods in Canada or elsewhere or importing goods produced outside Canada.

Under the Supply Chains Act, a government institution has the same meaning as in section 3 of the Access to Information ActFootnote 2 (AIA) (see footnote below):

- any department or ministry of state of the Government of Canada, or any body or office, listed in Schedule I; and

- any parent Crown corporation, and any wholly-owned subsidiary of such a corporation, within the meaning of section 83 of the Financial Administration ActFootnote 3 (see footnote below).

An entity means a corporation or a trust, partnership or other unincorporated organization that:

- is listed on a stock exchange in Canada;

- has a place of business in Canada, does business in Canada or has assets in Canada and that, based on its consolidated financial statements, meets at least two of the following conditions for at least one of its two most recent financial years:

- it has at least $20 million in assets,

- it has generated at least $40 million in revenue, and

- it employs an average of at least 250 employees; or

- is prescribed by regulations.

Reporting requirements for government institutions and entities

In accordance with subsections 6(1) and 11(1) of the Supply Chains Act:

6(1) The head of every government institution must, on or before May 31 of each year, report to the Minister [of Public Safety] on the steps the government institution has taken during its previous financial year to prevent and reduce the risk that forced labour or child labour is used at any step of the production of goods produced, purchased or distributed by the government institution.

11(1) Every entity must, on or before May 31 of each year, report to the Minister [of Public Safety] on the steps the entity has taken during its previous financial year to prevent and reduce the risk that forced labour or child labour is used at any step of the production of goods in Canada or elsewhere by the entity or of goods imported into Canada by the entity.

Additionally, subsections 6(2) and 11(3) require that each report provided by a government institution or entity includes the following information:

- its structure, activities and supply chains;

- its policies and due diligence processes in relation to forced labour and child labour;

- the parts of its activities or business and supply chains that carry a risk of forced labour or child labour being used and the steps it has taken to assess and manage that risk;

- any measures taken to remediate any forced labour or child labour;

- any measures taken to remediate the loss of income to the most vulnerable families that results from any measure taken to eliminate the use of forced labour or child labour in its activities and supply chains;

- the training provided to employees on forced labour and child labour; and

- how the government institution or entity assesses its effectiveness in ensuring that forced labour and child labour are not being used in its activities or business and supply chains.

Publication of reports

Reports submitted to Public Safety Canada are made publicly available in a searchable online catalogueFootnote 4 (see footnote below) on the Public Safety Canada website in accordance with section 22 of the Supply Chains Act. Reporting government institutions and entities must also make the report available to the public, including by publishing it in a prominent place on the government institution or entity’s website, as stipulated by section 8 and subsection 13(1) of the Supply Chains Act.

Requirements for reporting to Parliament

Subsection 24(1) requires the Minister of Public Safety to table a report to Parliament on the Supply Chains Act on or before September 30 of each year. The report must contain:

- a general summary of the activities of government institutions and entities that provided a report under the Supply Chains Act for their previous financial year that carry a risk of forced labour or child labour being used;

- the steps that government institutions and entities have taken to assess and manage that risk;

- if applicable, measures taken by government institutions and entities to remediate any forced labour or child labour;

- a copy of any order made pursuant to section 18; and

- the particulars of any charge laid against a person or entity under section 19.

Public Safety Canada’s implementation progress

Public Safety Canada was created in 2003 to ensure coordination across all federal departments and agencies responsible for national security and the safety of Canadians. The Supply Chains Act names Public Safety Canada as the federal department responsible for administering and enforcing the new reporting obligation. As a government institution listed in Schedule I of the AIA, Public Safety Canada is also required to submit its own annual report under the Supply Chains Act.

For the first reporting cycle, Public Safety Canada focused its implementation efforts on establishing the report intake process, issuing guidance for government institutions and entities and conducting targeted engagement to increase awareness of the reporting requirements.

Guidance and stakeholder engagement

In December 2023, Public Safety Canada published a new websiteFootnote 5 (see footnote below), containing guidance on preparing and submitting a report, information on the application of the Supply Chains Act and a list of tools and resources. Tailored guidance for government institutions was added to the website in March 2024. The department also hosted targeted technical briefings for entities and government institutions, which were attended by over 1200 stakeholders, and met with numerous stakeholder groups and associations on an ad-hoc basis to answer questions about the reporting process. Public Safety Canada manages an inbox dedicated to public inquiries and continues to engage with a range of stakeholders (including industry associations, law firms, consulting firms and civil society groups) on the requirements of the Supply Chains Act.

Online questionnaire

To facilitate the report intake process, Public Safety Canada developed an online questionnaire for government institutions and entities to complete when submitting their annual reports to the Minister of Public Safety. The questionnaire was designed to collect the information necessary to satisfy the mandatory reporting requirements under the Supply Chains Act, as well as to collect identifying information. The data collected through the questionnaire will enable the department to measure progress year over year.

Annual report on the Fighting Against Forced Labour and Child Labour in Supply Chains Act

About the data analysis

This report was developed using analysis of the data collected through the online questionnaire, with a view to summarizing the outcomes of the 2024 reporting cycle. The accuracy of the findings presented in this report is contingent on the quality and completeness of the information submitted to Public Safety Canada by government institutions and entities, as well as their understanding of the reporting requirements.

To capture data that could not be gathered using quantitative analysis, qualitative analysis was conducted on a sample of reports. Examples are included in this report to provide insight into the types of risks and mitigation strategies that some government institutions and entities described in their reports. These reflect a data sample and are not representative of all submissions.

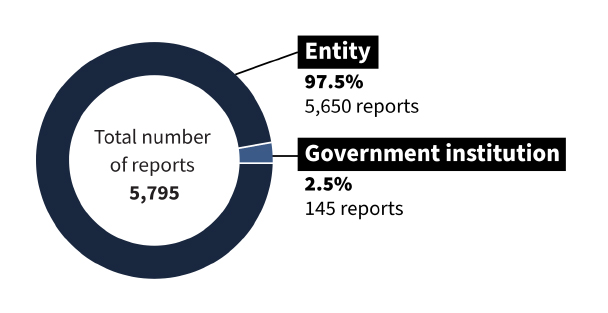

Overview of reports received by Public Safety Canada

Public Safety Canada received a total of 5,795 reports on or before the May 31 reporting deadline. Of these, 145 were submitted on behalf of government institutions and 5,650 were submitted on behalf of entities. All reports received on or before May 31 were considered for the data analysis in this report.

Image description

A donut chart with two slices showing the percentage and number of respondents submitting reports on behalf of entities and government institutions. A detailed breakdown of the results is available in Table 1 of the Annex.

Joint reports

Entities are able to submit a joint report as per subsection 11(2), which could cover, for example, a parent company and its subsidiaries or multiple entities belonging to the same corporate group. In 2024, Public Safety Canada received 2,086 joint reports.

Revised reports

Government institutions and entities can submit a revised report in order to make corrections or add additional information to their original submission. When submitting a revised report, government institutions and entities are required to state the date of revision and describe the changes made to the original report. Of the 5,795 reports received before the reporting deadline, 135 reports were revised reports, submitted in accordance with sections 7 and 12 of the Supply Chains Act.

Publication in the online catalogue

Public Safety Canada makes reports submitted under the Supply Chains Act available in a searchable online catalogue, which is updated on a regular basis. Note that some reports received by Public Safety Canada were not published in the online catalogue because they did not pass a quality assurance checkFootnote 6 (see footnote below).

Late submissions

To encourage transparency, Public Safety Canada continued to allow submissions after May 31, 2024. On July 31, 2024, the department had received a total of 6,303 submissions and continues to receive reports and post them in the online catalogue on an ongoing basis, with a note to identify those reports that came in late. For the purposes of the data within this report, only the 5,795 reports submitted before the reporting deadline were analyzed.

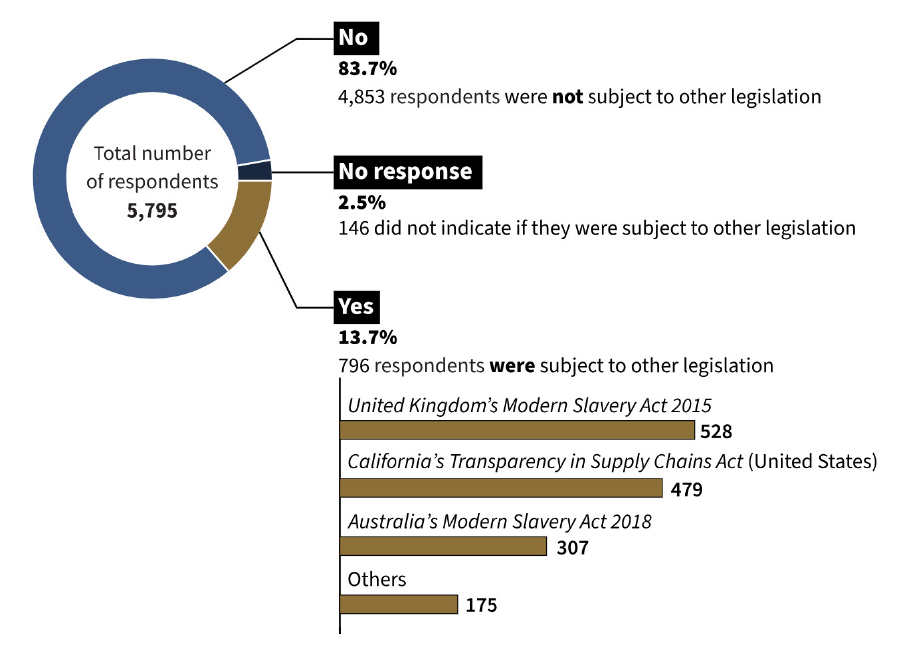

Entities subject to supply chain legislation in multiple jurisdictions

Recognizing that many reporting entities operate internationally, respondents were asked to indicate whether they are subject to reporting requirements under modern slavery or supply chain legislation in other jurisdictions.

Image description

A donut chart showing the percentage and count of respondents that are subject to supply chain legislation in multiple jurisdictions. A detailed breakdown of the percentage and count is available in table 2 of the Annex.

Of the 796 entities subject to supply chain legislation in multiple jurisdictions:

- 528 (66.3%) report under United Kingdom’s Modern Slavery Act 2015;

- 479 (60.2%) report under California’s Transparency in Supply Chains Act;

- 307 (38.6%) report under Australia’s Modern Slavery Act 2018; and

- 175 (22.0%) report under other legislation not listed above.

Breakdown of reporting government institutions

The Supply Chains Act applies to a range of federal departments and agencies, as well as federal Crown corporations and wholly-owned subsidiaries thereof. Of the 145 reports from government institutions, 53 (36.2%) were submitted on behalf of federal Crown corporations or subsidiaries based in the following provinces and territories: Alberta (3.9%), British Columbia (3.9%), Manitoba (3.9%), New Brunswick (1.9%), Nova Scotia (3.9%), Ontario (57.7%), Quebec (23.1%) and Saskatchewan (1.9%).

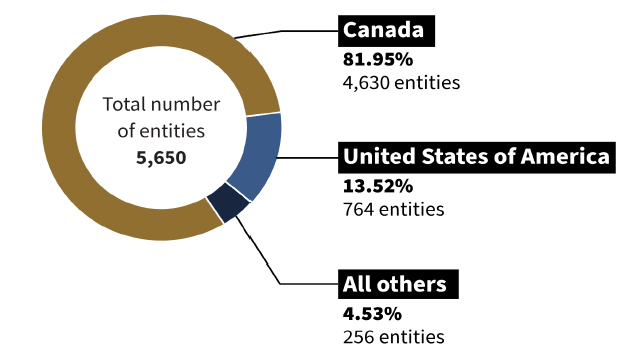

Breakdown of reporting entities

The entities that reported in 2024 represent a diversity of sectors and industries. Of note, the largest reporting sector category was manufacturing at 38.3%, followed closely by wholesale trade and retail trade at 22.3% and 21.8% respectively. Reports were submitted on behalf of entities based in Canada and around the world. Among reporting entities, 81.9% (4,630) indicated they are headquartered or principally located in Canada, and 18.1% (1,020) indicated they are in another country.

Image description

A donut chart showing the percentage and count of entities for reporting entity countries of Canada, the United States of America, and the sum of all other reporting entity countries combined. A detailed breakdown of the percentage and count for Canada, the United States, and the 38 other reporting entity countries is available in Table 3 of the Annex.

Summary of activities that carry a risk of forced labour and child labour

The Supply Chains Act requires government institutions and entities to report on the parts of their activities or business and their supply chains that carry a risk of forced labour or child labour being used (subsections 6(2)(c) and 11(3)(c)).

Gaining visibility into a complex supply chain can be difficult, and mapping possible risk areas is an ongoing process for any organization. Identifying a risk means it was determined there is some possibility that forced labour or child labour might be used at some point within the supply chain, but does not indicate that forced labour or child labour is certainly being used.

In the online questionnaire, government institutions and entities were asked whether they had identified parts of their activities or business and supply chains that carry a risk of forced labour or child labour being used and the types of risk areas they had identified, if any. They were also given an opportunity to provide additional information, if desired.

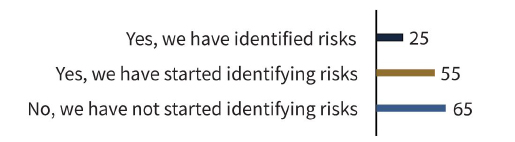

Government institutions

- 17.2% (25) government institutions had identified parts of their activities and supply chains that carry a risk of forced labour or child labour being used;

- 37.9% (55) had started the process of identifying risks but highlighted there were still gaps in their assessments; and

- 44.8% (65) had not started the process of identifying risks.

Image description

A horizontal bar chart showing the number of participants for the three differential responses to the question of whether government institutions have identified risks of forced labour or child labour in their activities and supply chains. A detailed breakdown of the results is available in Table 4 of the Annex.

Government institutions identified forced labour or child labour risks related to the following aspects of their activities and supply chains:

- the types of products the government institution sources (21 responses);

- the raw materials or commodities used in its supply chains (10 responses);

- direct suppliersFootnote 7 (10 responses);

- tier 3 suppliers (8 responses); and

- the sector or industry it operates in (7 responses).

Government institutions that elaborated on their answers most often listed products, sectors and industries as the reasons for increased risks of forced labour or child labour.

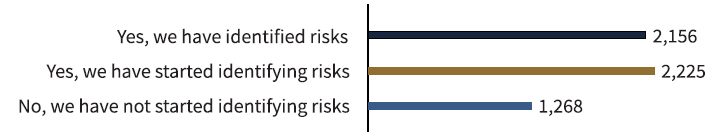

Entities

- 38.2% (2,156) of entities confirmed they had identified parts of their activities and supply chains that carry a risk of forced labour or child labour being used;

- 39.4% (2,225) had started the process of identifying risks but highlighted there were still gaps in their assessments; and

- 22.4% (1,268) had not started the process of identifying risks.

Image description

A horizontal bar chart showing the number of respondents by entities who identified a risk of forced labour or child labour being used in their organization’s activities and supply chains. A detailed breakdown of the results is available in Table 4 of the Annex.

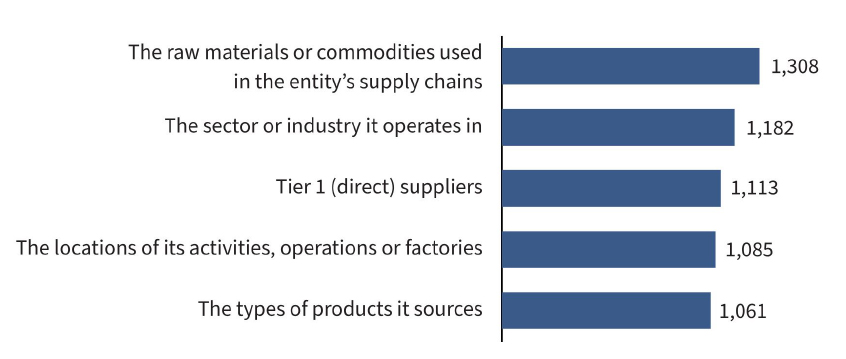

Entities identified forced labour or child labour risks related to the following aspects of their activities and supply chains:

- the raw materials or commodities used in the entity’s supply chains (1,308 responses);

- the sector or industry it operates in (1,182 responses);

- tier 1 (direct) suppliers (1,113 responses);

- the locations of its activities, operations or factories (1,085 responses); and

- the types of products it sources (1,061 responses).

Image description

A horizontal bar chart showing the number of participants responding on behalf of entities that identified forced labour or child labour risks by aspects of activities and supply chains. The horizontal bar chart shows the top five aspects with the most entity responses in descending order: the raw materials or commodities used in the entity’s supply chains (1,308 responses); the sector or industry it operates in (1,182 responses); direct suppliers (1,113 responses); the locations of its activities, operations or factories (1,085 responses); and the types of products it sources (1,061 responses). A detailed breakdown of the results is available in Table 5 of the annex.

Entities identified risks of forced labour and child labour related to specific products, sectors or industries, specifically related to the procurement of electronics, property management services, food industry services and textiles.

“From multiple lines of business, [Entity] has identified the procurement of electronics (such as laptops, computers and mobile phones, etc.) to likely have the highest risk.”

“In addition, there may be potential risks of modern slavery in procurement of services from third-party vendor industries and external labour services such as cleaning, property and facilities maintenance, security guard services, food services, transportation services, courier services, accommodation (hotels), and call centres.”

Some entities noted that in their supply chains, there were unknown levels of risk due to a lack of visibility into the practices of indirect suppliers and subcontractors.

“We have less visibility into contractual protections that our direct suppliers impose on downstream suppliers related to human rights.”

Some entities acknowledged that risks of forced labour and child labour are higher when temporary or migrant workers are employed, especially due to these workers’ vulnerable position in society.

“There are inherent risks of forced labour, particularly concerning the recruitment of temporary foreign workers through intermediaries such as employment agencies or middlemen in their home countries. These entities might exploit workers by charging excessive fees for job placements abroad.”

Efforts to assess and manage risks of forced labour and child labour

This section responds to paragraph 24(1)(b) of the Supply Chains Act, which requires that the annual report include a description of “the steps that government institutions and entities have taken to assess and manage [risks of forced labour and child labour].”

Government institutions and entities that report having identified risks of forced labour or child labour are asked to describe the steps they have taken to assess and manage those risks (paragraphs 6(2)(c) and 11(3)(c)). However, regardless of whether they have identified risks in their activities or supply chains, government institutions and entities are asked to list and describe any preventative measures they have in place, including:

- their policies and due diligence processes in relation to forced labour and child labour (paragraphs 6(2)(b) and 11(3)(b));

- the training they provide to employees on forced labour and child labour (paragraphs 6(2)(f) and 11(3)(f)); and

- their methods for assessing their effectiveness in ensuring that forced labour and child labour are not used in their activities or business and their supply chains (paragraphs 6(2)(g) and 11(3)(g)).

Government institutions and entities were able to identify more than one step to prevent forced labour and child labour in the online questionnaire.

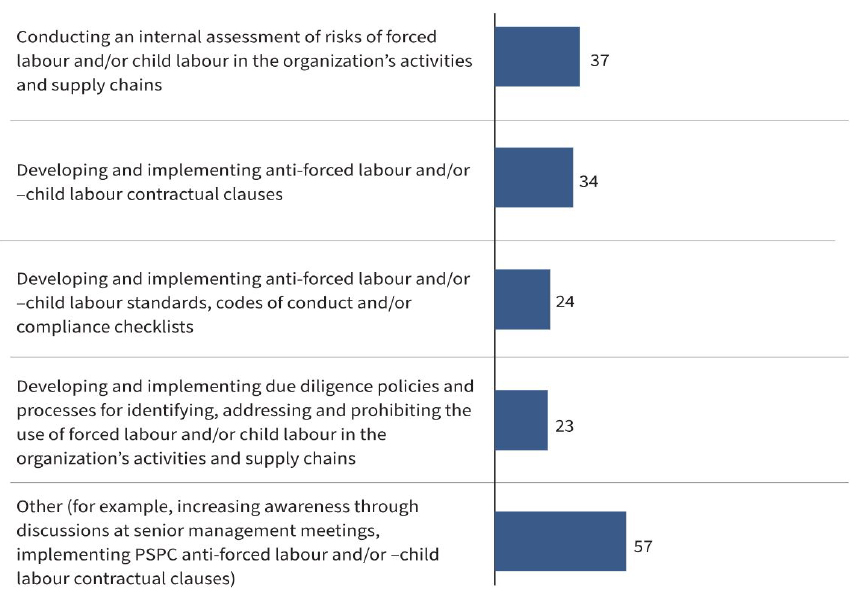

Government Institutions

Steps taken to prevent and reduce forced labour and child labour risks

The most common steps taken by government institutions in the previous financial year to prevent and reduce the risk that forced labour or child labour was used in their activities or supply chains include:

- conducting an internal assessment of risks of forced labour and/or child labour in the organization’s activities and supply chains (37 responses);

- developing and implementing anti-forced labour and/or -child labour contractual clauses (34 responses);

- developing and implementing anti-forced labour and/or -child labour standards, codes of conduct and/or compliance checklists (24 responses);

- developing and implementing due diligence policies and processes for identifying, addressing and prohibiting the use of forced labour and/or child labour in the organization’s activities and supply chains (23 responses); and

- other (for example, increasing awareness through discussions at senior management meetings, and implementing Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) anti-forced labour and/or -child labour contractual clauses) (57 responses).

Image description

A horizontal bar chart showing the number of participants responding on behalf of government institutions that outlines the steps their organization has taken to prevent and reduce the risk of forced labour or child labour. The horizontal bar chart shows the top five steps with the most government institution responses: conducting an internal assessment of risks of forced labour and/or child labour in the organization’s activities and supply chains (37 responses); developing and implementing anti-forced labour and/or -child labour contractual clauses (34 responses); developing and implementing anti-forced labour and/or -child labour standards, codes of conduct and/or compliance checklists (24 responses); developing and implementing due diligence policies and processes for identifying, addressing and prohibiting the use of forced labour and/or child labour in the organization’s activities and supply chains (23 responses); and other aspects (for example, increasing awareness through discussions at senior management meetings, implementing PSPC anti-forced labour and/or -child labour contractual clauses) (57 responses). A detailed breakdown of the results is available in Table 6 of the Annex.

The most common strategy for mitigating risks of forced labour and child labour was implementing a mandatory supplier code of conduct.

Policies and due diligence processes

46.9% of government institutions reported having policies and due diligence processes in place related to forced labour and/or child labour.

Training provided to employees

When asked if their organization currently provides training to employees on forced labour and/or child labour, 26 government institutions (17.9%) responded that they did and 119 (82.1%) responded that they did not. Of those that indicated they currently provide training:

- 3.8% (1) indicated that the training was mandatory for all employees;

- 46.2% (12) had mandatory training for employees making contracting or purchasing decisions;

- 23.1% (6) had mandatory training for some employees; and

- 26.9% (7) had voluntary training.

Assessing effectiveness in preventing the use of forced labour and child labour

When asked if they have policies and procedures in place to assess their effectiveness in ensuring that forced labour and child labour are not being used in their activities and supply chains, 20 government institutions (13.8%) indicated they did and 125 (86.2%) indicated they did not.

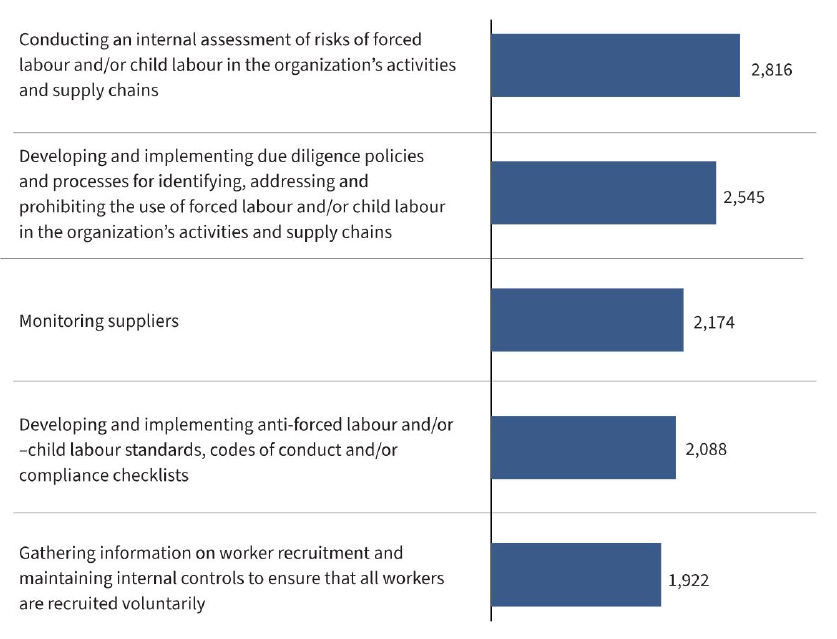

Entities

Steps taken to prevent and reduce forced labour and child labour risks

In terms of steps entities had taken in their previous financial year to reduce risks of forced labour and/or child labour, the following were most common:

- conducting an internal assessment of risks of forced labour and/or child labour in the organization’s activities and supply chains (2,816 responses);

- developing and implementing due diligence policies and processes for identifying, addressing and prohibiting the use of forced labour and/or child labour in the organization’s activities and supply chains (2,545 responses);

- monitoring suppliers (2,174 responses); and

- developing and implementing anti-forced labour and/or -child labour standards, codes of conduct and/or compliance checklists (2,088 responses).

Image description

A horizontal bar chart showing the number of participants responding on behalf of entities with the steps their organization has taken to prevent and reduce the risk of forced labour or child labour. The horizontal bar chart shows the top five steps with the most entity responses: conducting an internal assessment of risks of forced labour and/or child labour in the organization’s activities and supply chains (2,816 responses); developing and implementing due diligence policies and processes for identifying, addressing and prohibiting the use of forced labour and/or child labour in the organization’s activities and supply chains (2,545 responses); monitoring suppliers (2,174 responses); developing and implementing anti-forced labour and/or -child labour standards, codes of conduct and/or compliance checklists (2,088 responses); and gathering information on worker recruitment and maintaining internal controls to ensure that all workers are recruited voluntarily (1,922 responses). A detailed breakdown of the results is available in Table 6 of the Annex.

The most common step mentioned by entities with respect to preventing and reducing risks was regular auditing and monitoring. Examples included screening potential suppliers, vendors and/or partners through the use of software programs, as well as conducting internal or third-party audits.

“[We] make use of the services of third-party monitoring organizations or certification bodies to independently assess compliance with labour standards, including the absence of forced labour and child labour, within the supply chain.”

“The due diligence process also includes… background checks, examination of… red flags… and a review of higher-risk suppliers’ names against human trafficking watch lists and sanctions lists. If we discover red flags, we conduct extensive and documented follow-ups to address these issues.”

Some entities reported that they require suppliers, vendors and/or partners to fill out self-assessment questionnaires. Many stated that they have implemented a mandatory code of conduct for suppliers, vendors and/or partners.

“Our entities are also requiring our suppliers to complete a Supplier Assessment related to sustainability that specifically asks about their policies and protocols relating to labour and human rights issues.”

“If a vendor breaches the terms of the Compliance Certification, [Entity] can take various actions, including withholding payment for invoices or terminating its agreement and business relationship with the vendor. These actions can be taken with written notice, effective immediately.”

Many entities had also developed strategies to reduce risks of forced labour and child labour when choosing their supply chain partners. Some entities reported having specific hiring practices intended to reduce forced labour and child labour risks, including screening for age and other vulnerabilities.

“We select suppliers and service providers who are reputable, and comply with domestic and international laws.”

“To address this risk, [Entity] does not engage any recruitment agencies for hiring temporary foreign workers. Instead, we directly recruit candidates… A few months post-recruitment, we conduct confidential one-on-one interviews with temporary foreign workers to confirm that they haven't paid any fees for their employment with us.”

Many entities reported having processes in place to allow for issues to be raised anonymously and without repercussion, for example through hotlines and other grievance mechanisms. Some mentioned that they have developed remedial action plans for use if cases of forced labour or child labour are identified.

“We also sponsor confidential hotlines run by NGOs for supply chain workers, providing advice on workers’ rights and confidential support.”

Some entities also mentioned the use of working groups, committees, stakeholder engagements and engagements with unions as vehicles to address forced labour and child labour issues.

Policies and due diligence processes

71.3% of entities (4,031) reported having policies and due diligence processes related to forced labour and/or child labour in place. Manufacturing was the leading sector, followed by wholesale trade and retail trade. See Table 7 in the Annex for a breakdown by sector of organizations that reported having policies and due diligence processes in place.

Training provided to employees

44.4% of entities (2,506) indicated that they provide training to their employees on forced labour and/or child labour. Of those:

- 39.8% (998) indicated that the training was mandatory for all employees;

- 22.6% (567) indicated that the training was mandatory for employees making contracting or purchasing decisions;

- 29.1% (730) indicated that the training was mandatory for some employees; and

- 8.4 % (210) indicated that the training was voluntary.

Manufacturing was the top sector with respect to employee training, with 1,132 entities from the manufacturing sector reporting that they provide training to their employees on forced labour and child labour. For a breakdown by sector of organizations that provide training, see Table 8 in the Annex.

Assessing effectiveness in preventing the use of forced labour and child labour

43.5% of entities (2,455) confirmed they have policies and procedures in place to assess their effectiveness in ensuring that forced labour and child labour are not being used in their activities and supply chains. For additional information on the methods that organizations used to assess effectiveness, see Table 9 in the Annex.

Monitoring key performance indicators (KPIs) and conducting annual reviews are ways in which many entities reported mitigating risks of forced labour and child labour. Some KPIs mentioned in entities’ description of their efforts were:

- number of cases of forced labour and/or child labour reported and solved;

- number of contracts with anti-forced labour and -child labour clauses;

- number of employees taking relevant training;

- age and number of hours worked per employee; and

- number of suppliers, vendors and/or partners that have signed a code of conduct.

Efforts to remediate forced labour and child labour

This section responds to the requirement in paragraph 24(1)(c) of the Supply Chains Act to include, if applicable, a description of “measures taken by government institutions and entities to remediate any forced labour or child labour.”

The Supply Chains Act requires government institutions and entities to report on any measures they have taken to remediate any forced labour or child labour in their activities and supply chains (paragraphs 6(2)(d) and 11(3)(d)).

When a business or other organization amends or terminates its activities to avoid the use of forced labour or child labour (for example, ending a relationship with a supplier or pulling operations out of a country), there may be unintended consequences that contribute to lost income for workers and families. If applicable, government institutions and entities must also report on any measures they have taken to remediate the loss of income to the most vulnerable families that results from any measure taken to eliminate the use of forced labour or child labour (paragraphs 6(2)(e) and 11(3)(e)).

Government Institutions

Measures taken to remediate instances of forced labour or child labour

Out of 145 government institutions that submitted a report:

- three (2.1%) indicated they had taken remediation measures and will continue to identify and address any gaps in their response;

- two (1.4%) shared that they had taken some remediation remedies, but acknowledged there are gaps that need to be addressed;

- 30 (20.7%) indicated they had not taken any remediation measures; and

- 110 (75.9%) indicated that the question was not applicable.

When asked to specify what actions were taken to remedy instances of forced labour or child labour:

- one government institution indicated they had implemented actions to support victims and/or their families, such as workforce reintegration and psychosocial support;

- two indicated they had implemented actions to prevent forced labour or child labour and associated harms from recurring;

- three had grievance mechanisms;

- one had given formal apologies;

- three identified another action; and

- none indicated that they had compensated victims and/or their families.

Measures taken to remediate the loss of income to the most vulnerable families

When asked if they had taken any measures to remediate the loss of income to the most vulnerable families that results from any measures taken to eliminate the use of forced labour or child labour in the government institution’s activities and supply chains, 33 government institutions (22.8%) responded that they had not taken any such remediation measures and 112 (77.2%) answered that it was not applicable.

Entities

Measures taken to remediate instances of forced labour or child labour

Of the 5,650 entities that submitted a report:

- 228 (4%) indicated they had taken remediation measures and will continue to identify and address any gaps in their response;

- 88 (1.6%) indicated that they had taken some remediation measures, but acknowledged there are gaps that still need to be addressed;

- 392 (6.9%) indicated they had not taken any remediation measures; and,

- 4941 (87.5%) indicated that the question was not applicable.

For a breakdown by sector of the organizations that have taken remediation measures, see Table 10 in the Annex.

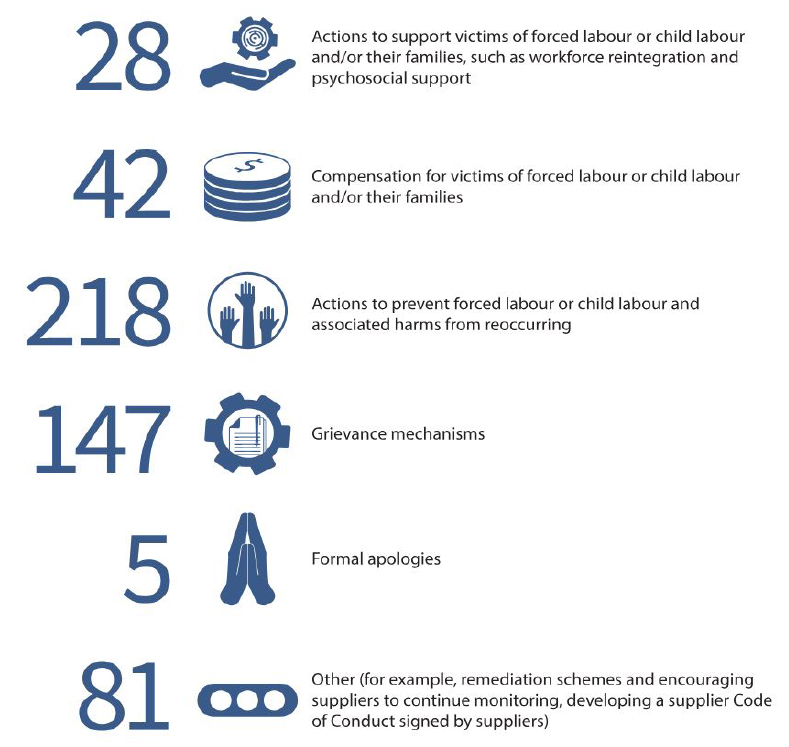

A breakdown of specific actions taken by entities that indicated they had implemented remediation measures is displayed in the figure below.

Image description

An image which reads: 218 had put in place actions to prevent forced labour or child labour and associated harms from recurring; 147 had grievance mechanisms; 42 had provided compensation for victims and/or their families; 28 had implemented actions to support victims and/or their families, such as workforce reintegration and psychosocial support; 5 had given formal apologies; and 81 had implemented other remediation measures (for example, encouraging suppliers to continue monitoring and implementing remediation schemes, developing a supplier Code of Conduct signed by suppliers). A detailed breakdown of the results is available in Table 11 of the annex.

Some entities provided examples of issues that created risks and the need for remedial action, including:

- poor working conditions;

- suspected use of prison labour;

- government-issued IDs being taken from workers by their employers;

- high recruitment fees; and

- workers not being fully informed of their rights before entering the country.

Some entities reported on the specific remedial actions they had taken, such as reimbursing workers for recruitment fees taken by employment agencies.

“We identified risks related to coercion and harassment, discrimination, restriction of movement, excessive working hours, and lack of access to remedy. We are working closely with the respective production partners to remediate the issues and prevent reoccurrence in the future.”

“[Entity] has confirmed remedy to more than 1,400 workers in our supply chain, including over $2.81 million USD in fee repayments in FY23.”

Measures taken to remediate the loss of income to the most vulnerable families

When asked if they had taken any measures to remediate the loss of income to the most vulnerable families that results from any measures taken to eliminate the use of forced labour or child labour in their activities and supply chains, 42 entities (0.7%) confirmed they had taken substantial remediation measures and will continue to identify and address any gaps, 23 (0.4%) said they had taken some remediation measures but that gaps remained in their responses, 442 (7.8%) said they had not taken any remediation measures and 5,142 (91.0%) said it was not applicable.

Corrective measures, offences and punishments

This section responds to the requirements in subsection 24(1) paragraphs (d) and (e) of the Supply Chains Act to include “a copy of any order made pursuant to section 18” and “the particulars of any charge laid against a person or entity under section 19.”

Under section 14, the Minister many designate persons or classes of persons for the purposes of the administration and enforcement of the Supply Chains Act. Sections 15 and 16 provide a designated person with the authority to verify compliance with the Supply Chains Act. Section 17 requires that a person must not obstruct or hinder a designated person who is exercising powers or performing duties under the Supply Chains Act.

Under section 18, where the Minister is of the opinion that an entity is not in compliance with section 11 or 13, based on information obtained under section 15, the Minister may require the entity to take any measures that the Minister considers necessary to ensure compliance with those provisions.

Section 19 provides that a person or entity that fails to comply with section 11 or 13, subsection 15(4) or an order made under section 18, or that contravenes section 17, is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction and liable to a fine of not more than $250,000.

In the first year of reporting, recognizing that the goal of the Supply Chains Act is to increase industry awareness and transparency about risks of forced labour and child labour, Public Safety Canada prioritized raising awareness of the reporting requirements to encourage meaningful action.

In 2024, no orders were made pursuant to section 18 and no charges were laid against any person or entity under section 19.

Annex: Data tables

Note about the data tables: Respondents were allowed to select multiple responses for some questions in the online questionnaire, so the total count may add up to more than the total number of submissions received (5,795), and the total percentage may add up to more than 100%.

| Entity | Government Institution | |

|---|---|---|

| Count | 5,650 | 145 |

| Percentage | 97.5% | 2.5% |

This table displays the number of reports submitted on behalf of entities and the number of reports submitted on behalf of government institutions.

| No | Yes | No response | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Count | 4,853 | 796 | 146 |

| Percentage | 83.7% | 13.7% | 2.5% |

This table displays how many organizations are subject to supply chain legislation in multiple jurisdictions.

| Other applicable legislation | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom’s Modern Slavery Act 2015 | 528 | 66.3% |

| California’s Transparency in Supply Chains Act (United States) | 479 | 60.2% |

| Australia’s Modern Slavery Act 2018 | 307 | 38.6% |

| Other, please specify | 175 | 22% |

This table indicates which legislation applies to those respondents that answered “Yes.”

| Canada | United States | All others | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Count | 4,629 | 764 | 257 |

| Percentage | 82.0% | 13.5% | 4.5% |

This table displays the number of reports submitted on behalf of entities based in Canada, the United States and other countries.

| We have identified risks | Started the process | Not started the process | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entities | 2,156 (38.2%) | 2,225 (39.4%) | 1,268 (22.4%) |

| Government institutions | 25 (17.2%) | 55 (37.9%) | 65 (44.8%) |

This table displays responses to the question of whether an organization has identified the parts of its activities and supply chains that carry a risk of forced labour or child labour being used.

| Aspect of activities and supply chains | Entity count | Government institution count |

|---|---|---|

| The raw materials or commodities used in its supply chains | 1,308 | 10 |

| The sector or industry it operates in | 1,182 | 7 |

| Tier 1 (direct) suppliers | 1,113 | 10 |

| The locations of its activities, operations or factories | 1,085 | 3 |

| The types of products it sources | 1,061 | 21 |

| The types of products it produces, sells, distributes or imports | 995 | 0 |

| Tier 2 suppliers | 743 | 6 |

| The use of outsourced, contracted or subcontracted labour | 632 | 5 |

| Tier 3 suppliers | 589 | 8 |

| Suppliers further down the supply chain than tier 3 | 561 | 6 |

| Other, please specify | 533 | 23 |

| The use of migrant labour | 431 | 3 |

| The use of forced labour | 405 | 4 |

| The use of child labour | 383 | 4 |

| None of the above | 0 | 0 |

This table displays aspects of activities and supply chains for which risks were identified by government institutions and entities.

| Step taken to reduce risks of forced labour and child labour | Entity count | Government institution count |

|---|---|---|

| Conducting an internal assessment of risks of forced labour and/or child labour in the organization’s activities and supply chains | 2,816 | 37 |

| Developing and implementing due diligence policies and processes for identifying, addressing and prohibiting the use of forced labour and/or child labour in the organization’s activities and supply chains | 2,545 | 23 |

| Monitoring suppliers | 2,174 | 10 |

| Developing and implementing anti-forced labour and/or -child labour standards, codes of conduct and/or compliance checklists | 2,088 | 24 |

| Gathering information on worker recruitment and maintaining internal controls to ensure that all workers are recruited voluntarily | 1,922 | 3 |

| Requiring suppliers to have in place policies and procedures for identifying and prohibiting the use of forced labour and/or child labour in their activities and supply chains | 1,911 | 11 |

| Developing and implementing training and awareness materials on forced labour and/or child labour | 1,824 | 14 |

| Mapping supply chains | 1,775 | 17 |

| Engaging with supply chain partners on the issue of addressing forced labour and/or child labour | 1,643 | 11 |

| Developing and implementing anti-forced labour and/or -child labour contractual clauses | 1,615 | 34 |

| Developing and implementing grievance mechanisms | 1,537 | 3 |

| Mapping activities | 1,523 | 16 |

| Developing and implementing an action plan for addressing forced labour and/or child labour | 1,443 | 12 |

| Auditing suppliers | 1,301 | 3 |

| Developing and implementing child protection policies and processes | 1,253 | 2 |

| Addressing practices in the organization’s activities and supply chains that increase the risk of forced labour and/or child labour | 1,168 | 8 |

| Carrying out a prioritization exercise to focus due diligence efforts on the most severe risks of forced and child labour | 1,031 | 8 |

| Other, please specify | 944 | 57 |

| Contracting an external assessment of risks of forced labour and/or child labour in the organization’s activities and supply chains | 851 | 9 |

| Information not available for this reporting period | 626 | 29 |

| Enacting measures to provide for, or cooperate in, remediation of forced labour and/or child labour | 542 | 2 |

| Engaging with civil society groups, experts and other stakeholders on the issue of addressing forced labour and/or child labour | 526 | 9 |

| Engaging directly with workers and families potentially affected by forced labour and/or child labour to assess and address risks | 113 | 0 |

This table provides a breakdown the steps that entities and government institutions have implemented to reduce the risk that forced or child labour is used in their activities or business and their supply chains.

| Sector | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing | 1,717 | 504 |

| Wholesale trade | 964 | 328 |

| Retail trade | 841 | 421 |

| Other, please specify | 762 | 267 |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | 378 | 121 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 373 | 131 |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 341 | 161 |

| Construction | 316 | 200 |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 262 | 67 |

| Health care and social assistance | 149 | 73 |

| Real estate and rental and leasing | 105 | 86 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 99 | 67 |

| Utilities | 99 | 46 |

| Accommodation and food services | 95 | 50 |

| Finance and insurance | 90 | 23 |

| Public administration | 77 | 35 |

| Other services (except public administration) | 67 | 26 |

| Educational services | 53 | 38 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 51 | 32 |

| Information and cultural industries | 35 | 11 |

| Administrative and support, waste management and remediation services | 26 | 11 |

This table displays responses to the question of whether an organization currently has policies and due diligence processes in place related to forced labour and/or child labour. The table includes responses from entities and from government institutions that indicated they are Crown corporations.

| Sector | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing | 1,132 | 1,089 |

| Wholesale trade | 627 | 665 |

| Retail trade | 536 | 726 |

| Other, please specify | 493 | 536 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 241 | 263 |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | 229 | 270 |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 185 | 317 |

| Construction | 168 | 348 |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 163 | 166 |

| Health care and social assistance | 89 | 133 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 59 | 107 |

| Utilities | 58 | 87 |

| Accommodation and food services | 58 | 87 |

| Finance and insurance | 58 | 55 |

| Real estate and rental and leasing | 51 | 140 |

| Public administration | 47 | 65 |

| Other services (except public administration) | 44 | 49 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 24 | 59 |

| Information and cultural industries | 21 | 25 |

| Educational services | 18 | 73 |

| Administrative and support, waste management and remediation services | 12 | 25 |

This table displays responses to the question of whether an organization currently provides training to its employees on forced labour and/or child labour. The table includes responses from entities and from government institutions that indicated they are Crown corporations.

| Method for assessing effectiveness | Entity count | Government institution count |

|---|---|---|

| Setting up a regular review or audit of the organization’s policies and procedures related to forced labour and child labour | 1,576 | 8 |

| Working with suppliers to measure the effectiveness of their actions to address forced labour and child labour, including by tracking relevant performance indicators | 842 | 2 |

| Tracking relevant performance indicators, such as levels of employee awareness, numbers of cases reported and solved through grievance mechanisms and numbers of contracts with anti-forced labour and -child labour clauses | 768 | 4 |

| Other, please specify | 587 | 12 |

| Partnering with an external organization to conduct an independent review or audit of the organization’s actions | 522 | 2 |

This table displays the methods identified by government institutions and entities that answered “Yes” when asked if they currently have policies and procedures in place to assess their effectiveness in ensuring that forced labour and child labour are not being used in their activities and supply chains.

| Sector | Substantial remediation measures taken | Some remediation measures taken | No remediation measures taken | Not applicable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing | 18 | 11 | 162 | 2,030 |

| Wholesale trade | 15 | 5 | 94 | 1,178 |

| Retail trade | 13 | 9 | 106 | 1,134 |

| Other, please specify | 5 | 4 | 72 | 948 |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 5 | 3 | 46 | 448 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 3 | 2 | 44 | 455 |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | 2 | 1 | 30 | 466 |

| Accommodation and food services | 2 | 1 | 11 | 131 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 2 | 0 | 19 | 145 |

| Public administration | 2 | 0 | 12 | 98 |

| Other services (except public administration) | 2 | 0 | 7 | 84 |

| Construction | 1 | 2 | 39 | 474 |

| Health care and social assistance | 1 | 0 | 31 | 190 |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 1 | 0 | 17 | 311 |

| Utilities | 1 | 0 | 15 | 129 |

| Real estate and rental and leasing | 1 | 0 | 12 | 178 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 1 | 0 | 7 | 75 |

| Finance and insurance | 0 | 1 | 5 | 107 |

| Educational services | 0 | 0 | 12 | 79 |

| Information and cultural industries | 0 | 0 | 3 | 43 |

| Administrative and support, waste management and remediation services | 0 | 0 | 2 | 35 |

This table displays responses to the question of whether an organization has taken any measures to remediate instances of forced labour or child labour in its activities or supply chains.

| Remediation measure | Entity count | Government institution count |

|---|---|---|

| Actions to prevent forced labour or child labour and associated harms from reoccurring | 218 | 2 |

| Grievance mechanisms | 147 | 3 |

| Other, please specify | 81 | 3 |

| Compensation for victims of forced labour or child labour and/or their families | 42 | 0 |

| Actions to support victims of forced labour or child labour and/or their families, such as workforce reintegration and psychosocial support | 28 | 1 |

| Formal apologies | 5 | 1 |

This table displays the measures taken by government institutions and entities to remediate instances forced labour or child labour in their activities or supply chains.

- Date modified: