2016-2017 Evaluation of the Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements

Executive Summary

Program evaluations support accountability to Parliament and Canadians by helping the Government of Canada to credibly report on the results achieved with resources invested in programs. Evaluation supports deputy heads in managing for results by informing them about whether their programs are producing the outcomes that they were designed to achieve, at an affordable cost. Evaluation also supports policy and program improvements by helping to identify lessons learned and best practices.

What we examined

The Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangement program (DFAA) is a federal transfer payment program that provides financial assistance to a province/territory (PT) for a natural disaster that is declared a provincial/territorial emergency to be of concern to the federal government. More specifically, the purpose of the program is to support an affected PT after a major natural disaster to assist with response and recovery costs that would exceed the PT's financial capacity.

Given the purpose of the DFAA, the scope of this evaluation was calibrated to primarily focus on the program's efficiency and economy. The evaluation also examined issues of relevance and effectiveness. The evaluation covered the period from 2011-2012 to 2015-2016.

Why it is important

In the event of a large-scale natural disaster, PTs can incur a substantial financial burden as they respond and recover. To lessen this financial burden, DFAA program staff work closely with PTs to review and provide financial assistance to reimburse eligible response and recovery costs. Since its inception in 1970, DFAA has reimbursed over $4.1 billion in post-disaster assistance.

As a contribution program, DFAA is required to be evaluated every five years under section 42.1 (1) of the Financial Administration Act. DFAA was last evaluated in December 2011.

What we found

Relevance

There is a continued need for the DFAA. In view of the increasing frequency and costs of disasters, particularly floods, PTs continue to require the federal government's support with response and recovery costs.

According to the documents reviewed, natural disasters have become more prevalent in urban and rural Canadian communities. The average annual federal share of response and recovery costs of natural disasters paid under the DFAA has increased from $10 million in 1970-1995 to $110 million in 1996-2010 to $360 million in 2011-2016.

The federal government's roles and responsibilities related to the DFAA are outlined in the Emergency Management Act. Under section 4 (1) (j), the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness' responsibilities include providing financial assistance to a PT if: “(i) a provincial emergency in the province has been declared to be of concern to the federal government under section 7, (ii) the Minister is authorized under that section to provide the assistance, and (iii) the province has requested assistance".Note 1

DFAA is aligned with Public Safety Canada's (PS) strategic outcome and Government of Canada's priority of building a stronger and resilient Canada. The program's overall expected result is to financially support an affected PT after a large-scale natural disaster with response and recovery costs.

Performance

A review of program files found that between 2011 and 2016, the DFAA made payments to 47 percent of active files. Requests for payment are made for actual expenditures related to response, recovery, and sometimes mitigation, which can occur over a number of years. In fact, for events occurring prior to 2008, there was no limit on when the PTs could come in to seek payment. For events occurring since 2008, PTs have five years, from the date of Order in Council approval designating the event as one subject to DFAA provisions, to forward their final payment request, unless an extension is formally granted. As the expenses need to be fully paid and audited at provincial level before submission, it is difficult for PTs to always have accurate forecasts for when final payment requests to the federal government will be made. Owing to the quasi-statutory nature of the program, the unpredictability of natural disasters events, and the timing of the requests, the evaluation found that PTs did not always request payments in the years when funds were planned. Consequently, DFAA has had to reprofile funds year after year.

Although reprofiling of funds is a common and accepted financial transaction, it may be perceived as a budget lapse in public accounts. Furthermore, continual reprofiling is still time-consuming and presents a year-end workload. As such, PS officials are engaged in ongoing consultations with PTs and central agencies to find potential solutions to reduce the need for reprofiling funds through better forecasting. Reprofiling does not affect the program's ability to provide payments to PTs for response and recovery costs associated with a natural disaster.

Over the past year, the program has implemented a number of tools and processes to improve efficiency. Although it is too early to assess the impact of these changes on program efficiency, the program has reduced its administration ratio from an average of 4.8 percent identified in the 2011 evaluation to 1.5 percent over the last five years.

Some of the interviewees suggested that DFAA could gain additional efficiencies, particularly in regards to the audit processes. There is a need to standardize provincial submissions and to enhance complementarity between federal and provincial audits to avoid duplication.

Documents reviewed revealed that greater attention to or investment in mitigation can reduce social, economic and environmental costs and damages when an event occurs. In 2008, DFAA integrated mitigation payments that allow PTs to receive potentially up to 15 percent of the estimated cost for repair and rebuilding projects that reduce vulnerability to future emergencies. According to DFAA guidelines, the program makes mitigation payments only at the final payment step, which can take five years. The evaluation found that the program has recently made three mitigation payments. However, it is too early to assess the impact of the 15 percent DFAA mitigation payments on PTs' vulnerability to future disasters. Currently, PTs are requesting mitigation payments for 17 additional events.

The evaluation identified a few opportunities for improvement. The following recommendations are provided in the spirit of continuous improvement.

Recommendations

The ADM of the Emergency Management and Programs Branch should:

- Update guidelines and templates to increase their effectiveness in ensuring consistency of PTs submissions;

- Establish, in collaboration with PTs, criteria and mechanisms whereby audits conducted by PTs complement and streamline federal audit requirements;

- Further promote the use of the DFAA mitigation component to reduce the financial burden of future disasters on PTs and the federal government.

Management Response and Action Plan

Management accepts all recommendations and will implement an action plan.

1. Introduction

This report presents the results of Public Safety Canada's 2016-2017 Evaluation of the Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements (DFAA). The DFAA was last evaluated in December 2011.

The evaluation was conducted in accordance with Government of Canada 2009 Policy on Evaluation and in compliance with section 42.1 (1) of the Financial Administration Act, which requires that all programs of grants and contributionsNote 2 be evaluated at least once every five years.

2. Profile

2.1 Background

In Canada, emergency management adopts an all-hazards approach to address both natural and human-induced hazards and disasters. This approach consists of four interdependent components: 1) prevention and mitigation, 2) preparedness, 3) response; and 4) recovery. These components are coordinated and integrated to maximize the safety of Canadians. All levels of government are responsible for emergency management. In 2007, the federal, provincial and territorial governments adopted the Emergency Management Framework for Canada, which represents a common approach to emergency management across Canada. The frameworkNote 3 was revised and approved in 2011.

Municipal, provincial and territorial governments provide the first response to the vast majority of emergencies. They are responsible for designing and administering programs to assist local communities. When disasters are beyond the capacity of provinces or territories (PTs), they may call on the federal government for financial assistance.Note 4 The Governor in Council may, on the recommendation of the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, declare a provincial emergency to be of concern to the Government of Canada (GC) and may authorize the provision of financial assistance to a PT by applying the DFAA terms and conditions. The GC established this transfer payment program in 1970. The terms and conditions of the program have been periodically reviewed since inception.

The DFAA set the terms and conditions under which the federal government provides financial assistance to PTs for response and recovery costs that might otherwise significantly burden a local economy and exceed the amount that PTs might reasonably be expected to fully bear on their own. The program is intended to address natural disasters that extensively affect people, damage property or disrupt the delivery of essential goods.Note 5 In 2008, the DFAA integrated mitigation measures into its programming. PTs can receive up to 15 percent of the estimated costs of repair to pre-disaster condition to reduce vulnerability to future disasters.

2.2 Program Administration

The DFAA guidelines spell out which PT disaster expenses are eligible for federal financial assistance and how the program administers funding. The guidelines (which reflect the terms and conditions approved by the Treasury Board of Canada) state that provincial expenditures must have been paid out to be eligible for reimbursement. As of January 1, 2016, the initial threshold for all new events is defined as $3.03 per capita of the provincial population (as estimated by Statistics Canada to exist on July 1st in the calendar year of the disaster). Once the threshold is exceeded, the federal government provides financial assistance for eligible expenses as determined by the formula in Table 1. Federal financial assistance increases as the size of the PT response and recovery expenditures increases. The formula is revised annually based on inflation and takes effect on January 1 each year.Note 6

Eligible Expenditures (per capita) |

Federal Share |

|---|---|

First $3.03 per capita |

Nil |

Next $6.07 per capita |

50% |

Next $6.07 per capita |

75% |

Remainder |

90% |

The decision to authorize the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness to authorize financial assistance rests with the Governor in Council. The Governor in Council may, on the recommendation of the Minister, make the order required by the Emergency Management Act declaring a provincial emergency to be of concern to the GC and authorizing the Minister to provide a financial assistance to the PT.

2.3 Resources

Since its inception, the DFAA has provided funding in the order of $4.1 billion.Note 7 As Table 2 illustrates, between 2011-2012 and 2015-2016, the program paid $1.8 billion which represents almost 45 percent of the total payments made by the program since its inception.

TRANSFER PAYMENTS (Vote 5) |

2011-12 |

2012-13 |

2013-14 |

2014-15 |

2015-16 |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Contribution paid |

99,970,212 |

279,948,809 |

1,018,988,056 |

305,271,755 |

139,348,326 |

1,843,527,158 |

2.4 Program Logic Model

A logic model is a visual representation that links what a program is funded to do (activities) with what it produces (outputs) and what it intends to achieve (outcomes). It also provides the basis for developing an evaluation matrix that provides a framework for the evaluation. The logic model for the recovery sub-program including the DFAA is in Annex A.

PS's emergency management program supports PTs to enhance their capacities and promote public awareness of emergency management to Canadians and businesses through outreach and various fora. The recovery sub-program provides leadership, direction, coordination and support at all levels so that individuals, businesses and communities affected by disaster have the resources and support needed to fully recover. This support includes financial assistance, upon request, to PTs recovering from large-scale disasters.

3. About the Evaluation

3.1 Objective and Scope

The evaluation provides a neutral, evidence-based assessment of the relevance and performance (i.e. effectiveness, efficiency and economy) of the DFAA.

The evaluation methodology and effort take into consideration the following factors:

- The DFAA is formula-based and provides reimbursement based on a federal audit of PT requests for payment. As such, the risk of “non-performance” is low.

- Relevance is already established due to DFAA's nature.

- A review was completed in 2006 to modernize the DFAA and to address several issues raised by stakeholders. Following this review, and given the nature of the program, PS proposed subsequent reviews every 10 years. A review is being considered for 2017. The last evaluation was conducted in 2011.

Based on the above factors, it was decided that the evaluation should primarily focus on the efficiency and economy of the program, and to a lesser extent, its relevance and effectiveness.

The evaluation covered the program activities from 2011-2012 to 2015-2016.

3.2 Methodology

The evaluation was conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board of Canada 2009 Policy on Evaluation, the Standard on Evaluation for the Government of Canada, the Policy on Transfer Payments, and the Financial Administration Act.

3.2.1 Evaluation Core Issues and Questions

The evaluation addressed the following questions:

Relevance

- What needs does the DFAA Program address?

- To what extent is the program aligned with government priorities and the federal roles and responsibilities?

Performance – Effectiveness

- To what extent has the program achieved its expected outcomes?

Performance – Efficiency and Economy

- To what extent has the program been delivered efficiently and economically?

- Have the recommendations from the 2011 evaluation been implemented as planned?

- Are there alternative approaches to achieve the intended outcomes more efficiently and economically?

3.2.2 Lines of Evidence

The evaluation used the following three lines of evidence to assess the questions:

Document Review

To assess DFAA's alignment with federal roles and government priorities as well as program effectiveness, departmental reports (i.e. Reports on Plans and Priorities, Departmental Performance Reports) were reviewed. To address the question of alternative approaches, evaluation reports on the Agricultural Disaster Relief Program and the Emergency Management Assistance Program were reviewed. To assess the question of economy, a number of studies and reports on the cost-benefit of mitigation were examined. Annex A provides a list of scanned documents that were consulted.

Interviews

Nine interviews were conducted with program staff including regional staff (3), federal auditors (3) and senior management (3). Interviews focused on the administrative aspect of the program to address the issue of efficiency.

Analysis of Performance and Financial Information

The evaluation reviewed claim files and program administrative files from 2011-2012 to 2015-2016 and analyzed financial information to address the issue of efficiency and economy.

3.3 Limitations

- Given that a review of the DFAA Program is being considered for 2017, the evaluation team opted not to consult PTs. To compensate, the evaluation team conducted a comprehensive document review.

- Although program management was able to provide some performance information, the evaluation findings and conclusions could have been stronger and better supported had there been a systematic data collection system in place.

- As a result of the structural realignment in the department, the new DFAA team has been in place only for a year. As such, it is too early to assess the impact of the new processes and tools that have been put in place on the program efficiency.

3.4 Protocols

This report was submitted to managers and the responsible Assistant Deputy Minister for review and acceptance. Program management prepared a Management Response and Action Plan in response to the evaluation recommendations. These documents will be presented to the Departmental Performance Measurement and Evaluation Committee for consideration and for final approval by the Deputy Minister.

4. Findings

4.1 Relevance

4.1.1 Continued Need

The DFAA was created to provide financial assistance to PTs for response and recovery costs that might otherwise significantly burden their economy and exceed the amount that PTs might reasonably be expected to fully bear on their own. According to the documents reviewed, natural disasters are increasing globally in number, frequency, and severity. For instance, between 1970 and 2015, the number of recorded disasters increased from 97 to 353 world-wide.Note 9 Canada is no exception to this global trend as natural disasters have become more prevalent in Canadian communities.Note 10

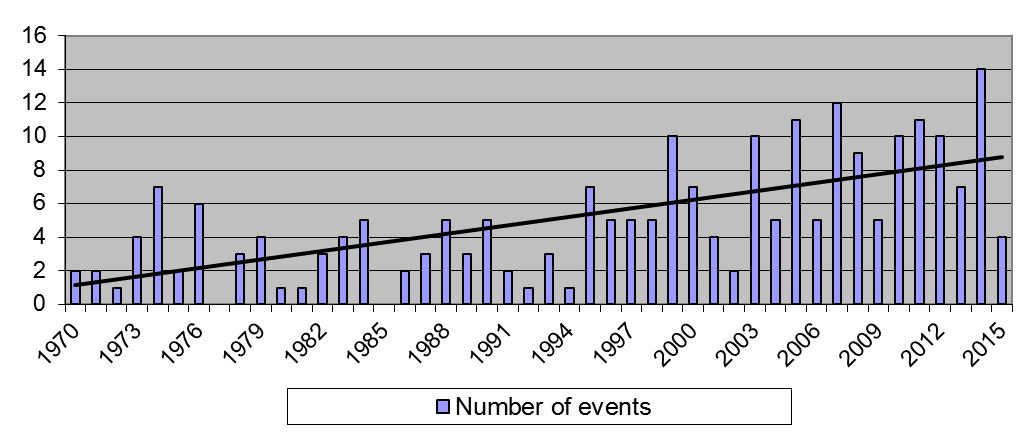

Since its inception in 1970, the DFAA has been applied to 240 events. As exhibited in Figure 1, the number of natural disasters for which PTs required and obtained federal assistance under the DFAA also increased between 1970 and 2015.

Figure 1: Trend in number of events in CanadaNote 11

Image description

Year |

Number of Events |

|---|---|

1970 |

2 |

1971 |

2 |

1972 |

1 |

1973 |

4 |

1974 |

7 |

1975 |

2 |

1976 |

6 |

1977 |

0 |

1978 |

3 |

1979 |

4 |

1980 |

1 |

1981 |

1 |

1982 |

3 |

1983 |

4 |

1984 |

5 |

1985 |

0 |

1986 |

2 |

1987 |

3 |

1988 |

5 |

1989 |

3 |

1990 |

5 |

1991 |

2 |

1992 |

1 |

1993 |

3 |

1994 |

1 |

1995 |

7 |

1996 |

5 |

1997 |

5 |

1998 |

5 |

1999 |

10 |

2000 |

7 |

2001 |

4 |

2002 |

2 |

2003 |

10 |

2004 |

5 |

2005 |

11 |

2006 |

5 |

2007 |

12 |

2008 |

9 |

2009 |

5 |

2010 |

10 |

2011 |

11 |

2012 |

10 |

2013 |

7 |

2014 |

14 |

2015 |

4 |

The table above was assembled to provide more depth to Figure 1 by showing the individual values of the yearly number of disaster events from 1970 to 2015 (which were too numerous to include in the graph). Though naturally there is some fluctuation in the numbers, the data illustrates an overall positive trend. Therefore, this indicates an increase in the annual number of hazardous events occurring through the years, which are then associated with a progressive increase of annual costs.

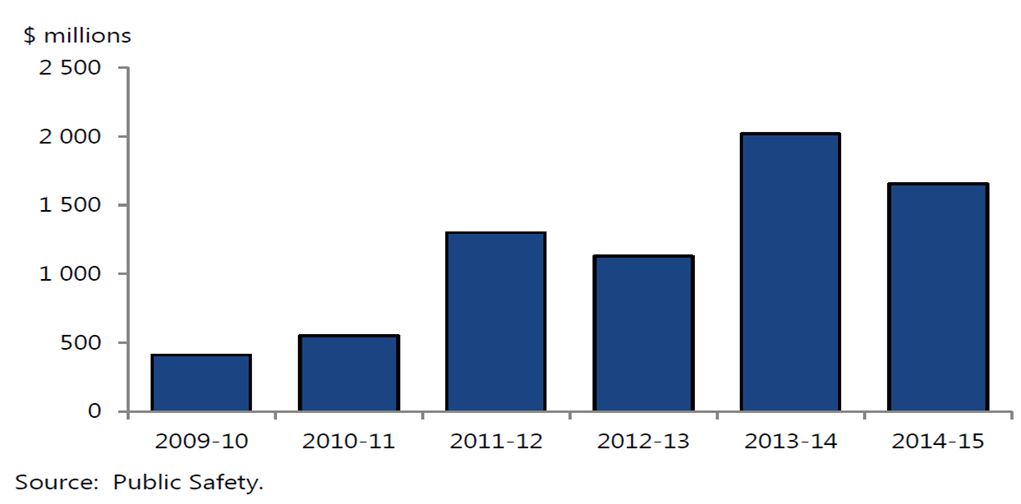

Documents and file reviews revealed that the costs associated with disasters are increasing. Similarly, over the past 20 years, the DFAA for weather events has been steadily increasing due to an increasing number of large weather events with greater intensity.Note 12 The average annual federal share of response and recovery costs has increased from $10 million (1970-1995) to $110 million (1996-2010)Note 13 to $360 million (2011-2016).Note 14 Over the past six fiscal years, the DFAA provided more recovery funding than in its first 39 fiscal years combined.Note 15

Figure 2: Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements Liabilities

Image description

The graph above represents the yearly Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements Liabilities from 2009 to 2015. Within the timeframe of 2009-2010, $400 million was owed. In 2010-2011, $600 million was owed. In 2011-2012, the numbers drastically rise to reach a total of $1300 million (1.3 billion) in liabilities. To continue, 2012-2013 had liabilities of $1200 million (1.2 billion). The timeframe of 2013 -2014 is the one in which the DFAA reached the highest liabilities at $2100 million (2.1 billion). Finally, 2014-2015 had liabilities of $1700 (1.7 billion).

A 2016 report by the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer estimated that DFAA will devote 75 percent of its weather related expenditures to flood recovery in the next five years. Between 2005 and 2014, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta accounted for 82 percent of all DFAA weather event costs, almost all of which were a result of flooding.Note 16 A review of open files found from 2010-2015, 78 percent of incidents were floods. StormsNote 17 comprised 12 percent and fires 10 percent.

Documents reviewed and interviews revealed that floods may cost so much because only three provinces (Ontario, Alberta and Quebec) offer flood insurance. Even in those provinces, such insurance is not available for high-risk properties, or if it is available, it is expensive.Note 18 This increases the overall cost of flooding.

Documents reviewed indicated that several trends affect the frequency and severity of weather events: climate change, environmental change, demographic transition, and urbanization; these trends are expected to continue to grow over the coming years.Note 19 The Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer estimates that over the next five years, DFAA can expect annual costs of $229 million per year because of hurricanes, convective storms and winter storms. Using the Insurance Bureau of Canada estimate for flood losses, the Parliamentary Budget Officer estimates that on average, DFAA can expect annual costs of $673 million for floods. Therefore, the total annual costs to the DFAA for weather events are estimated to be $902 million.Note 20

4.1.2 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Emergency Management responsibilities in Canada are shared by federal, provincial and territorial governments and their stakeholders. PTs have responsibility for emergency management within their respective jurisdictions. The Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness has the mandate for exercising leadership relating to emergency management in Canada by coordinating, among federal government institutions and in cooperation with the provinces and other entities, emergency management activities as outlined in the Emergency Management Act.

Under section 4 (j) of this Act, the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness's responsibilities include providing financial assistance to a PT if: “(i) a provincial emergency in the province has been declared to be of concern to the federal government under section 7, (ii) the Minister is authorized under that section to provide the assistance, and (iii) the province has requested assistance." As such, the DFAA is well-aligned with the Minister's roles and responsibilities.

4.1.3 Alignment with Government Priorities and PS Strategic Outcome

PS's strategic outcome is to build a safe and resilient Canada. The GC, through the DFAA, provides up to 90 per cent of eligible expenses for disaster recovery to PTs and works with other levels of government to build safer and more resilient communities.Note 21 The program's overall expected result is that Canadians are prepared for and can respond to both natural and human-induced hazards and disasters. This result aligns with the Government's priority of modernizing emergency management in Canada to strengthen community resilience, in collaboration with PTs, Indigenous communities and municipalities. Specifically, the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness's 2016 mandate letter references that PS will work with PTs, Indigenous Peoples and municipalities to develop a comprehensive action plan that allows Canada to better predict, prepare for, and respond to weather-related emergencies and natural disasters.

4.2 Performance—Effectiveness

According to Departmental Performance Reports, from 2011-12 to 2014-15, DFAA has provided support to PTs to assist with response and recovery costs from major disasters. Between 2011-12 and 2015-16, there were 95 active files including disasters that occurred prior to 2008. For these 95 active files, the program made 78 different payments, which included 7 advanced, 36 interim and 35 final payments. It is important to note that before 2008, there was no limit of time for PTs to request DFAA funding. Therefore, there are payments for disasters that occurred before 2008 in the evaluation period.Note 22 In addition, the evaluation found that among the 95 active files, 53 were approved by the Governor in Council between 2011 and 2016. DFAA made payments for 25 of these 53 active files as illustrated in Annex C.

Although the program has been supporting PTs, a review of the financial information illustrates that the total estimated federal shareNote 23 for active event files, $3.8 billion, is higher than the actual amount issued in contributions, $1.6 billion.Note 24 This means that over the past five years, DFAA received payment requests from PTs and issued payments on almost half of the estimated potential requests. While this is not unexpected, given the timeframes within which PTs are able to make requests for final payment, DFAA has had to reprofile funds to subsequent years or set up payable at year end to balance the budget.Note 25 This supports interviewees who indicated that the program does not control as to when PTs make requests. If the program had more control over the timing of payment requests, there would likely be less volatility in the budget.

Interviewees mentioned the challenges of managing a program based on estimates, which are not always accurate and where program managers have no control over the timing of requests for payment. In order to address these challenges, the program is engaged in ongoing communication with PTs to determine appropriate and evergreen forecasts. In addition, an annual accounting exercise is instituted whereby PTs submit attestedNote 26 estimated expenditures and potential future liabilities for each disaster to which the DFAA are being applied. As of September 2015, PTs were required to submit this accounting twice a year (February/March and August/September) instead of just once a year to strengthen PS forecasting. PTs are also asked to identify upcoming payment requests, timing, and amount.

4.3 Performance—Efficiency

To address program efficiency, the evaluation looked at four factors: duplication and complementarity between the DFAA and other federal and PT programs, the measures taken to improve program administration, the current average DFAA administration ratio compared with that the 2011 evaluation and, the audit process.

PS's comprehensive all-hazards approach to coordinate and integrate prevention and mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery functions complements the DFAA and other PS Emergency Management programs. The National Disaster Mitigation Program (NDMP) and the DFAA are aligned but fund different activities related to emergency management.

According to interviewees and documents reviewedNote 27, there is no duplication between the DFAA and other federal financial disaster assistance programs.Note 28 The DFAA is the only federal program that gives financial assistance to PTs after natural disasters. Other federal programs that provide financial assistance after a disaster transfer it directly to either individual farmers (through Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada's Agricultural Disaster Relief Program) or First Nations communities (Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada's (INAC's) Emergency Management Assistance Program).

DFAA regularly consults with other federal departments and PTs to avoid duplication among programs at either level of government. In fact, it is part of the program's terms and conditions to ensure there is no duplication. Moreover, the DFAA federal audits consider the possibility of payment duplication.

To ensure complementarity and collaboration, DFAA also consults with the INAC's program team that administers expenditures for response and recovery following disasters on First Nations reserve land. The DFAA and provincial financial assistance programs complement one another.

Interviewees commented that the department's realignment initially resulted in inefficiencies because staff had a steep learning curve. Over the past year, with staff in place, the program has taken some measures to improve program efficiency. These measures have included:

- PTs are now required to submit attested estimated expenditures and potential future liabilities for each disaster twice a year instead of just once a year to improve forecasting;

- Regular meetings with Corporate Finance to speed up payment;

- Looking for possible flexibilities with advance/interim payments. This is not possible for the final payment because no change could be made after the payment;

- Bi-weekly calls between the program administration staff, the regions, and the audit team to discuss issues and reach consensus on issues and files;

- Weekly calls between the program administration staff and the audit team to discuss issues, risk assessments and audits;

- A dashboard that adds to the regional and federal synchronization;

- A common mailbox to organize all the comments; and

- Streamlining processes.

The file review looked at 35 open cases that contained the dates for both the request and the date of Order in Council and calculated how long this process had taken. On average, DFAA took 11 months to process claims. Interviewees mentioned, however, that duration can vary widely. For example, some cases took more than 20 months to process while others took less than six months. The length of the process depends on a variety of factorsNote 29 such as the PTs' provision of information. Delays can occur when PS and the PTs' go back and forth many times to gather documentation and obtain estimates. Interviewees commented the differences between provinces in estimating the costs and the need to develop a standard approach for PTs' submissions.

The program recently created efficiencies in processing of OICs. In April 2016, there were 19 outstanding OICs dating to 2014. To reduce this backlog, one staff member, supported by the departmental legal services focused solely on OICs and as a result, the Governor in Council approved 18 of the 19 by end of June 2016. An additional measure to ensure that the OICs are received in a timely manner was the implementation of a new template to be used by the program before sending the draft OIC to the departmental legal services for its review by Justice Canada.

A review of financial information combined with program estimates approximates the annual administrative cost of the DFAA varied between $1.73 million and $1.75 million over the last five years. Based on these costs, the average of administration ratiosNote 30 has been reduced from 4.8 percentNote 31 for the last evaluation period to 1.5 percent for this evaluation period. Details of the calculations are contained in Annex D.

Despite these noted efficiencies, interviewees commented that there was still room for improvement, particularly with audits. The 2011 DFAA evaluation recommended that the federal audit process be reviewed to evolve to a more risk-based approach. This recommendation was to be implemented in 2012-2013. Interviewees commented that the audit function has moved towards a risk-based approach only in the past year or two. They stated that during the last few months they have been trying to standardize and create efficiencies by identifying and removing unnecessary audit steps. For instance, DFAA used to produce an advisory report for each advance and interim payment. Under the new process, DFAA performs a risk assessment and an audit for the final payment only.

Interviewees identified duplication in the audit process, suggesting that clarification of DFAA guidelines would help avoid overlap between provincial and federal audits. In addition, interviewees noted inconsistencies in quality of PT submissions. Interviewees also commented on the time required to complete audits. The evaluation was unable to determine the average length of an audit since the number of files on which an audit had been conducted was very small and a review of the files did not reveal the audit dates and/or date of payments. Regular communication between program staff, the audit team, and the regions is believed to have led to efficiencies.

4.4 Performance—Economy

The growing unpredictability, number, and severity of disasters have increased in federal financial liability under the DFAA.Note 32 According to the documents reviewed, more emphasis on and investments in prevention and mitigation through Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) measures can help save lives; minimize the cost of response; and, lower the social, economic and environmental damages of such events.Note 33

In Canada, most of the large scale disasters are weather-relatedNote 34 events, particularly floods. From 2010-2015, 78 percent of the open files were floods. In 2015, the Insurance Bureau of Canada released a reportNote 35 examining key issues to flood financial risk management in Canada. According to the report, flood insurance coverage for overland flooding is historically limited in Canada for three main reasons. First, flood insurance is hard to offer as it is naturally expensive. Therefore, homeowners tend not to purchase this type of coverage. In addition, flood-related losses are generally due to lack of investment in public infrastructure, obsolete building codes and ineffective land-use planning. Finally, Canada lacks effective flood hazards maps, which are considered essential risk assessment tools. The cumulative effect of all of this is that if the risk is not assessable, its financial management would be difficult and limit its insurability.

Another report released by the Office of the Director of the Parliamentary Budget Officer in February 2016, estimated residential losses due to floods at $1.2 billion for the period 2016-2020. The amount reaches $2.4 billion for the same period when taking into account commercial and public infrastructures losses. The report estimated DFAA's average annual payments for 2016-2020 to be at $673 million for flood-related disasters.

Traditionally, emergency management in Canada has focused on preparedness and response. In January 2008, the federal government and PTs launched Canada's National Disaster Mitigation Strategy.Note 36 The Strategy was developed based on the agreement between the Government of Canada and PTs that mitigation is essential for a strong emergency management framework in support to disaster impacts mitigation in Canada.

In 2008, DFAA integrated mitigation into its programming by providing PTs up to 15 % of the estimated cost of repair of infrastructure to pre-disaster condition to reduce vulnerability to future disasters. The 15% mitigation payment under DFAA is aligned with Canada's National Disaster Mitigation Strategy. It is also aligned with Canada's international commitment under the Sendai 2015-2030 Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction.Note 37 The Framework clearly identifies mitigation through disaster risk reduction activities as the key approach to reduce costs. The document also stated that “building back better” and addressing the underlying risk factors would be more cost-effective than relying primarily on post-disaster response and recovery.

In March 2016, New Brunswick received DFAA mitigation funds totaling $157,397 for the 2008 spring flood, the 2008 summer storm and the 2008 tropical storm Hanna. Because DFAA paid the funds only recently, the evaluation team was unable to assess the impact of these mitigation payments based on the available program data. Currently, PS is aware of at least 17 events that would require mitigation payments. Literature review indicates that measures taken to reduce disaster risks could reduce both impacts on communities and recovery costs, and could offer significant returns on investment. For example, benefit-cost ratios for flood prevention measures in Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom are 3:1, 4:1 and 5:1, respectively. In Canada, $63.2 million that was invested in the Manitoba Red River Floodway in 1960, has resulted in an estimated saving of $8 billion in potential damage and recovery costs.Note 38

By emphasizing mitigation, Canada's infrastructure (e.g. public utilities, transportation systems, telecommunications, housing, hospitals, and schools) can be designed to withstand the impacts of extreme natural forces.

5. Conclusions

There is a continuing need for the DFAA program

DFAA is still relevant due to the increasing frequency, severity and costs of disasters affecting Canadian communities. PTs still need the federal government's support with response and recovery costs.

The Minister's role, authorities and responsibilities with regards to the DFAA are grounded in the Emergency Management Act and related Order-in-Councils declaring provincial emergencies of concern for the federal government. The Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness mandate letter references that PS will work with all levels of governments to develop a comprehensive action plan that allows Canada to better predict, prepare for, and respond to weather-related emergencies and natural disasters.

The DFAA is providing financial support to PTs but sometimes must reprofile funds, or set up a payable at year-end to balance its budget.

The evaluation found that PTs did not always request payments in the years when funds were planned. Therefore, DFAA has had to reprofile funds or create a payable at year-end each fiscal year. To reduce reprofiling, the program is implementing new tools and processes to get more accurate estimates from PTs. In addition, PS officials are engaged in ongoing consultations with PTs and central agencies to find potential solutions for reducing the need for reprofiling funds year after year.

There is some duplication between federal and provincial audits

Some interviewees indicated that there is some duplication between federal and provincial audits. The quality of DFAA submissions is inconsistent between provinces and there is ambiguity about the scope of the provincial audit in relation to the federal audit. The evaluation found that there are no service standards and was unable to determine the average time of the audit process.

Mitigation strategies are crucial to increase disaster resilience in Canada

Mitigation is the most effective approach to reduce costs associated with disaster recovery. The evaluation found that mitigation can improve disaster resilience of Canadian communities and reduce financial burden from future disasters.

The DFAA has made only a few mitigation payments since 2008. However, it is too early to assess the effectiveness of mitigation investments.

6. Recommendations

The ADM of the Emergency Management and Programs Branch should:

- Update guidelines and templates to increase their effectiveness in ensuring consistency of PTs submissions;

- Establish, in collaboration with PTs, criteria and mechanisms whereby audits conducted by PTs complement and streamline federal audit requirements;

- Further promote the use of the DFAA mitigation component to reduce the financial burden of future disasters on PTs and the federal government.

7. Management Response and Action Plan

The Programs Directorate has reviewed the report and the recommendations and is in agreement with the findings. The DFAA Guidelines are reaching the ten year mark and Programs will take the opportunity to consult the PT with the goal of simplifying the processes, clarifying the expectations and requirements, and establishing mechanisms to achieve complementarity in PT and federal audits. We will also continue to promote the use of the mitigation component and the innovative recovery solutions.

Recommendation |

Management Response |

Action Planned |

Planned Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|

Update guidelines and templates to increase their effectiveness in ensuring consistency of PTs submissions. |

Accept |

|

October 2017 |

Establish in collaboration with PTs, criteria and mechanisms whereby audit conducted by PTs complement and streamline federal audit requirements. |

Accept |

|

March 2018 |

Further promote the use of the DFAA mitigation component to reduce the financial burden of future disasters on PTs and the federal government. |

Accept |

|

March 2018 |

Annex A: Logic Model

Image description

The Logic Model works as a communication tool that summarizes the key elements of the program, explains the rationale behind program activities, and clarifies all intended outcomes. Consequently, the Annex A illustrates the inputs, activities and outputs needed to reach all outcomes.

The inputs are: 1. Governing instruments, 2. Management decisions, 3. Organizations, 4. Financial resources, 5. Human Resources, 6. Material Resources, 7. Data Information Knowledge, and 8. Goodwill.

The activities (used to implement the inputs) are: 1. Consult EM Stakeholders, 2. Set up and maintain EM partnerships with stakeholders, 3. Assess risks available resources potential for co-investment by stakeholders, and potential ROI in EM options, 4.Set Priorities, goals, and objectives for whole- of society EM, 5. Invest in and (as appropriate) lead, direct, provide guidance on, coordinate, monitor, and Evaluate and control EM research and innovation, plans, programs and other measures.

The outputs (result of the inputs and activities) are: 1. Financial Resources and 2. Information, guidance, and tools.

The outputs lead to the following immediate outcome: 1. Stakeholders take actions to manage and reduce the impact of all hazards risks.

The immediate outcome then leads to the following intermediate outcome: 1. A whole- of- society approach is used to promote a culture of prevention/mitigation that reduces all hazards risks.

The intermediate outcome leads to the following ultimate outcomes: 1. Federal Institutions have taken mitigative and preventative actions to address risk to Canadians and 2. Canada has the capacity to prevent and mitigate, prepare for, respond to, and recover from all hazards events.

The ultimate outcome leads to the strategic outcome of achieving a safe and resilient Canada.

Annex B: Documents Reviewed

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (2013). Audit of the Emergency Management Assistance Program.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (2011). Evaluation of the Agricultural Disaster Relief Program.

Australia and New Zealand School of Government, Cost-benefit analysis and multi-criteria analysis: Competing or complementary approaches?

Budget (2012, 2014).

C.M. Shreve, I. Kelman (2014). Does mitigation save? Reviewing cost –benefit analyses of disaster risk reduction.

D.Guha-Sapir et al. (2012). Annual Disaster Statistical Review 2011. The numbers and trends.

D. Kull, R. Mechler and S. Hochrainer-Stigler (2013).Probabilistic cost-benefit analysis of disaster risk management in a development context.

Emergency Management Act, 2007.

F.Khan et al. (2012). Understanding the cost and benefits of disaster risk reduction under changing climate conditions.

Francis Vorhies (2012). The economics of investing in disaster risk reduction.

Government of Alberta (2015). Alberta Disaster Assistance Guidelines.

Government of Saskatchewan (2015). Provincial Disaster Assistance Program. General Claim Guidelines.

Ilan Kelman (2014). Disaster Mitigation is Cost Effective.

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (2010). Evaluation of the Emergency Management Assistance Program.

Infrastructure Canada (2015). Evaluation of the Building Canada Fund-Communities Component.

Infrastructure Canada (2015). Audit of the New Building Canada Fund – Management Control Framework.

Insurance Bureau of Canada (2015). The financial management of flood risk.

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (2012). The long road to resilience. Impact and cost-benefit analysis of disaster risk reduction in Bangladesh.

K.Hawley, M.Moench and L.Sabbag (2012). Understanding the economics of flood risk reduction.

Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (2016). Disaster Recovery Assistance for Ontarians: Program Guidelines.

Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (2016). Municipal Disaster Recovery Assistance Program Guidelines.

Office of the Auditor General of Canada (2016). Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development. Report 2 Mitigating the Impacts of Severe Weather.

Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (2016) .Estimate of the Average Annual Cost for Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements due to Weather Events.

Public Safety Canada (2011). An Emergency Management Framework for Canada.

Public Safety Canada (2008). Canada's National Disaster Mitigation.

Public Safety Canada (2012). Evaluation of Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements.

Public Safety Canada. 2014-15 Departmental Performance Report.

Public Safety Canada (2007). Guidelines for the Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements.

Public Safety Canada (2015). Performance Measurement Strategies. Emergency Management Program.

Public Safety Canada. 2016-2017 Report on Plans and Priorities.

Speech from the throne (2013).

Annex C: DFAA Requests and Payments

PT |

Natural Disaster |

Total Estimated Federal Share - Active Event Files |

Paid To Date |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

NL |

2010 Hurricane Igor |

$85,800,000 |

$71,000,000 |

2 |

PE |

2010 December Storm |

$1,207,000 |

- |

3 |

NS |

2010 August Rainstorm |

$3,119,000 |

- |

4 |

NS |

2010 November Rainstorm |

$4,109,000 |

- |

5 |

NS |

2010 December 12-15 Rainstorm |

$617,000 |

- |

6 |

NS |

2010 December 20-22 Rainstorm |

$449,000 |

- |

7 |

NS |

2012 September Rainstorm |

$ 2,655,000 |

- |

8 |

NS |

2012 September 22-24 Rainstorm |

$686,000 |

- |

9 |

NB |

2010 December 5-7 Storm |

$1,414,000 |

- |

10 |

NB |

2010 December 12-15 Rainstorm |

$22,100,000 |

$5,000,000 |

11 |

NB |

2010 December 20-22 Rainstorm |

$1,519,000 |

$250,000 |

12 |

NB |

2012 Spring Flood |

$12,751,000 |

$5,000,000 |

13 |

NB |

2014 Spring Freshet |

$13,466,000 |

$7,000,000 |

14 |

NB |

2014 Post Tropical Storm Arthur |

$10,100,000 |

- |

15 |

QC |

2010 December 5-7 Storm |

$28,710,000 |

$10,000,000 |

16 |

QC |

2011 Spring Flood |

$80,720,000 |

$ 47,500,000 |

17 |

QC |

2011 Tropical Storm Irene |

$16,502,000 |

$5,000,000 |

18 |

ON |

2013 December Ice Storm |

$103,500,000 |

- |

19 |

MB |

2010 May Rainstorm |

$5,312,000 |

- |

20 |

MB |

2010 June Rainstorm |

$3,177,000 |

- |

21 |

MB |

2010 Wildfires |

$5,551,000 |

- |

22 |

MB |

2010 October Storm |

$5,365,000 |

- |

23 |

MB |

2011 Spring Flood |

$699,870,000 |

$350,000,000 |

24 |

MB |

2013 Spring Flood |

$17,007,000 |

- |

25 |

MB |

2013 June Rainstorm |

$4,186,005 |

- |

26 |

SK |

2010 June 16-18 Rainstorm |

$27,610,000 |

$10,000,000 |

27 |

SK |

2010 June 29-July 2 Storm |

$14,500,000 |

$ 5,000,000 |

28 |

SK |

2010 July 22 Storm |

$148,000 |

- |

29 |

SK |

2011 Spring Flood |

$252,000,000 |

$100,000,000 |

30 |

SK |

2010 Spring Flood |

$27,000,000 |

$10,000,000 |

31 |

SK |

2010 September Rainstorm |

$1,800,000 |

- |

32 |

SK |

2013 Spring Flood |

$43,000,000 |

$20,000,000 |

33 |

SK |

2014 June Rainstorm |

$147,000,000 |

$100,000,000 |

34 |

AB |

2010 June Rainstorm |

$63,100,000 |

$30,000,000 |

35 |

AB |

2011 May Rainstorm |

$4,385,000 |

- |

36 |

AB |

2011 June Rainstorm |

$4,557,000 |

- |

37 |

AB |

2011 July Rainstorm |

$3,222,000 |

- |

38 |

AB |

2011 Spring Flood |

$11,845,000 |

$6,000,000 |

39 |

AB |

2013 June Flood |

$1,477,000,000 |

$600,000,000 |

40 |

AB |

2012 June 5-6 Rainstorm |

$2,741,000 |

- |

41 |

AB |

2012 July Rainstorm |

$2,902,000 |

- |

42 |

AB |

2011 Wildfires |

$ 24,905,000 |

$16,000,000 |

43 |

AB |

2013 June 7-11 Rainstorm |

$21,743,000 |

- |

44 |

BC |

2010 Wildfires |

$37,100,000 |

$15,000,000 |

45 |

BC |

2010 September Rainstorm |

$49,033,000 |

$27,000,000 |

46 |

BC |

2011 June Rainstorm |

$49,524,000 |

$33,000,000 |

47 |

BC |

2011 September Rainstorm |

$9,728,000 |

$4,000,000 |

48 |

BC |

2012 Spring Freshet |

$9,843,000 |

$5,940,000 |

49 |

BC |

2013 June Rainstorm |

$ 8,804,000 |

$1,500,000 |

50 |

BC |

2014 Wildfires |

||

51 |

NT |

2012 June Rainstorm |

$1,533,000 |

- |

52 |

YK |

2010 December Flood |

$643,000 |

- |

53 |

YK |

2012 June Rainstorm |

$7,160,000 |

- |

TotalNote 39 |

$3,776,734,005 |

$1,599,690,000 |

Annex D: Financial Information

The amounts below represent the total estimated cost to the federal government ($ CA).

Program administration costs |

2011-2012 |

2012-2013 |

2013-2014 |

2014-2015 |

2015-2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Program Staff - up to the level of Director |

|||||

Salaries for Program Staff |

296423 |

296423 |

296423 |

296423 |

296423 |

Salaries for Audit |

1132000 |

1132000 |

1132000 |

1132000 |

1132000 |

Operations and Maintenance |

198000 |

198000 |

198000 |

198000 |

198000 |

Subtotal |

1,626,423 |

1,626,423 |

1,626,423 |

1,626,423 |

1,626,423 |

DG's office (10 % of Salaries) |

|||||

Salaries |

13390 |

13390 |

13390 |

13390 |

13390 |

Operations and Maintenance |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Subtotal |

13,390 |

13,390 |

13,390 |

13,390 |

13,390 |

Total program cost |

1,639,813 |

1,639,813 |

1,639,813 |

1,639,813 |

1,639,813 |

Internal Services (40 % of Salaries) |

|||||

Salaries |

576,725 |

576,725 |

576,725 |

576,725 |

576,725 |

Operations and Maintenance |

79,200 |

79,200 |

79,200 |

79,200 |

79,200 |

Subtotal |

655,925 |

655,925 |

655,925 |

655,925 |

655,925 |

Employee Benefits Plan |

403,707.64 |

403,707.64 |

403,707.64 |

403,707.64 |

403,707.64 |

PWGSC Accommodation Allowance |

262,409.97 |

262,409.97 |

262,409.97 |

262,409.97 |

262,409.97 |

Total program administration cost |

2,961,856 |

2,961,856 |

2,961,856 |

2,961,856 |

2,961,856 |

TRANSFER PAYMENTS (Vote 5) |

|||||

Budget |

100,000,000 |

280,000,000 |

1,019,000,000 |

312,000,000 |

139,385,000 |

Contribution paid |

99,970,212 |

279,948,809 |

1,018,988,056 |

305,271,755 |

139,348,326 |

Budget minus Contribution |

29,788 |

51,191 |

11,944 |

6,728,245 |

36,674 |

Program administration ratioNote 40 |

|||||

Annual |

3.0 % |

1.1 % |

0.3 % |

1.0 % |

2.1 % |

Five year average of ratios |

1.5 % |

Endnotes

- 1

The Governor in council may on the recommendation of the Minister make orders or regulations, among other things, declaring a provincial emergency to be of concern to the federal government; and authorizing the Minister to provide assistance to a province under paragraph 4(1)(j) of the Emergency Management Act.

- 2

The DFAA program is classified as a contribution program in PS 2016-17 Main Estimates (source of funding for DFAA is Vote 5).

- 3

https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/mrgnc-mngmnt-frmwrk/mrgnc-mngmnt-frmwrk-eng.pdf

- 4

Ibid.

- 5

DFAA Guidelines, 2007.

- 6

DFAA Guidelines, 2007.

- 7

DFAA June 28, 2016, presentation to DAC includes financial information up to March 31, 2016.

- 8

In fiscal year 2014-15, the budget amount differs from the budget shown in the Public Account due to a frozen amount of $450M to be reprofiled.

- 9

Sigma Insurance Research Global Trends.

- 10

An Emergency Management Framework for Canada , 2011; Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development. Report 2 Mitigating the Impacts of Severe Weather, Spring 2016.

- 11

Program data.

- 12

Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer. Estimate of the Average Annual Cost for Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements due to Weather Events, 2016.

- 13

Public Safety Canada (2012). Evaluation of the Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements Program.

- 14

DFAA Program Data. The amounts are not amortized.

- 15

Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development. Report 2 Mitigating the Impacts of Sever Weather, Spring 2016.

- 16

Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer. Estimate of the Average Annual Cost for Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements due to Weather Events, 2016.

- 17

Storms include hurricanes and the “other storms” category from the program but exclude rainstorms. Rainstorms were included as floods.

- 18

Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer. Estimate of the Average Annual Cost for Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements due to Weather Events, 2016.

- 19

An Emergency Management Framework for Canada 2011; Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer .Estimate of the Average Annual Cost for Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements due to Weather Events, 2016. Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Spring 2016.

- 20

Ibid, p.2.

- 21

Budget 2012; Budget 2014; DPR 2014-2015.

- 22

The 5-year limit was introduced in 2008 with possibility of extension.

- 23

Estimated federal share of an event may change following completion of federal audit.

- 24

These financial figures are for the 53 events that were approved by the Governor In Council between 2011 and 2016.

- 25

A PAYE (Payables at Year End) is set to ensure that liabilities existing at the fiscal year end are recorded in the accounts and financial statements of Canada. https://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pol/doc-eng.aspx?id=27784.

- 26

Attested at Senior Financial Officer level.

- 27

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (2013). Audit of the Emergency Management Assistance Program. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (2011). Evaluation of the Agricultural Disaster Relief Program. Public Safety Canada (2012). Evaluation of Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements.

- 28

The DFAA Guidelines mention that expenditures, for which provision is made for full or partial reimbursement to the PTs under any other existing federal program, at the time of the emergency, are not eligible to DFAA payment.

- 29

From time to time, the proximity of either a federal or a provincial election may impact the length of the process.

- 30

The program administration ratio refers to the total cost of program administration cost as a percentage of the total reimbursements to PTs in a given year.

- 31

2011-2012 Evaluation of Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements.

- 32

Report on Plans and Priorities 2014-2015.

- 33

The economics of investing in disaster risk reduction, 2012; Does mitigation save? Reviewing cost-benefit analysis of disaster risk reduction 2014. Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer .Estimate of the Average Annual Cost for Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements due to Weather Events, 2016; Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development Spring 2016; Appendix C Economic Analysis.

- 34

Floods, hurricanes, convective storms and winter storms.

- 35

http://assets.ibc.ca/Documents/Natural Disasters/The_Financial_Management_of_Flood_Risk.pdf

- 36

https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/mtgtn-strtgy/index-en.aspx

- 37

- 38

Ibid.

- 40

The program administration ratio refers to the total cost of program administration cost as a percentage of the total reimbursements to PTs in a given year.

For the 53 events that were approved by the Governor in Council between 2011 and 2016. As of June 30, 2016

- Date modified: